I’ve been seeing the fall of civilization in many different phenomena recently — in the Super Bowl LIX ads, in the Oscar victory of Anora, in Donald Trump’s 1987 visit to Russia, but let’s try to put this on a slightly more theoretical basis.

What I believe is going on is a fundamental shift in our self-conceptions, our belief of what makes the good life. We have gone, in a surprisingly rapid time, from a base of materialism to a base of biological determinism.

What do I mean by materialism? I mean the idea that there are a certain number of core goods, and if people have them, then they can consider themselves satisfied. Abraham Maslow famously put them in a pyramid — but, basically, it’s shelter, food, the ability to provide for one’s children, and in the modern world you can toss in heat and electricity as well. All those are downstream from having a job, and the logic of materialism runs that if everybody has a job then everybody will be satisfied. Thinking in psychological terms, we can see socialism, for instance, as an almost pure expression of this conception of the world. Socialism looks around the world in the era of the Industrial Revolution and says, ‘goods provide happiness, the goods of the world are at present unequally divided, therefore we will equally divide the goods of the world.’ Within that, there are several premises. The premise is that, once people have their sufficient goods, they will no longer have a desire to compete with others. The premise is that equitable sexual distribution is in effect — that ‘every Jack will have their Jill,’ which became reified in the famous prudery of the socialist countries. The premise is that equality is an acceptable outcome to people; that people’s primary interests are in looking after their material well-being as opposed to dominating or asserting themselves over others; and that so long as people are materially satisfied they will not grudge the satisfaction of others.

Socialism spelled all this out in a rigid orthodoxy, but most of this would be part-and-parcel of the ‘common sense’ of the entire Industrial Era. These premises show up in the labor movement, with its assertion of the fundamental dignity and equality of work; in Western liberalism with its drive towards the egalitarian, well-managed society of the future; and in Western conservatism with its ‘family values,’ its emphasis on the primacy of the nuclear family which tends to be seen as an expression of a religious imperative.

There is a moment in Halldór Laxness’ Tale of the Promised Land that gestures to a different dispensation and points the way out of this sensibility. “It was amusing when I went to America for the first time while in my twenties,” he wrote. “I had to fill out large questionnaires from the emigration office. One of the questions was, ‘Are you a polygamist?’ I, of course, answered this ‘No’… Then I read the next question, which presented me for the first time with great difficulty: ‘Are you in sympathy with polygamists?’ To this day I haven’t been able to answer this clearly.”

What Laxness found himself considering was a society built on biological determinism. Instead of working towards perfect equality, male life, under polygamy, becomes a constant struggle to win a larger number of mates — to earn more than others, to defeat rival males for some large number of women, and to be in dominant relations towards those female partners. Polygamy, as Laxness intuited, is a kind of reversal of all the other values of Western society. It replaces the ethic of material equality with an ethic of domination. And it replaces material satisfaction as the goal of a good life with a goal of endless acquisition and drama — once you make it, goes the logic of polygamy, then it’s time to start adding to the family.

Polygamy entered into Western life from a few curious directions. Out of the belly of 19th century conservative Christianity, Joseph Smith fashioned a polygamous society dedicated above all to his own biological self-assertion. Successful males always had the possibility of mistresses — a practice that became something of an art form in France in particular. The sexual revolution meant above all a breakdown in the underlying premise of monogamy — free love would give way in time to what David Brooks calls the bobo phenomenon, where a looseness in sexual mores is a badge of sophistication. Immigration meant contact with different types of sexual cultures — the premise of Michel Houellebecq’s Submission, for instance, is traditional Western culture giving way to the greater power of Islamic polygamy.

The logic of biological determinism showed up not only in the sexual marketplace. It’s a little difficult to identify where the ‘adversarial system’ entered into the culture. It’s built into business, with different vendors competing with one another. It’s the very premise of law, with lawyers strenuously fighting one another in order, in theory, to help a judge see the strongest arguments for both sides and in this convoluted way arrive at truth. It’s in the notion of a free press or ‘loyal opposition’ — with the society held in a state of creative tension. And it’s in what have become the ‘best practices’ of major firms, with different working groups encouraged to compete with one another under the theory that competition brings out the best in people. At some point, what seems to have happened is that these theories of competition jumped the gate and became the core identity of professional people. For most people in the workforce, their job is not working towards the betterment of society or ensuring greater cooperation. Their job is to serve their company or maybe their industry, to be in a competitive relationship with any rivals and then ideally to secure dominance, to drive the rivals out of the market and to win the pot for themselves. We can call this a feature of capitalism if we like, but what I am more interested in is the underlying psychology of it — that the prevailing workplace ethic for the majority of professionals isn’t offering a good in exchange for material satisfaction (that’s what’s demeaningly called ‘a subsistence job’) but is the great game of defeating the competition.

Together with the rise of polygamy and advent of the adversarial system is a new theory of human psychology, which is evolutionary biology. Evolutionary biology is basically Social Darwinism, which was close to the leading social theory of the late 19th century, then went underground for a long time and has re-emerged largely through pop treatments of scientific findings. The guiding premise of evolutionary biology, as it has made its way into the culture, is that the purpose of human life is to maximize our own reproductive outcomes. For women, this is by choosing high-status mates; for men, by maximizing reproductive opportunities.

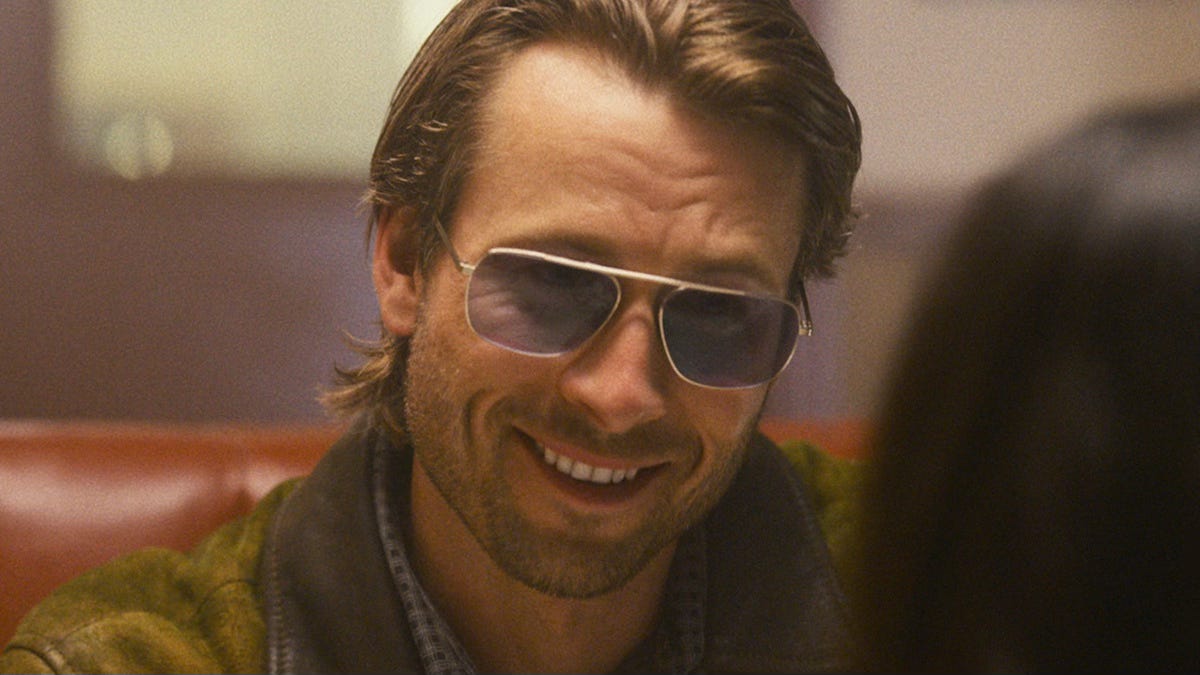

The key word is “optimization” and comes to serve as the ethic of the time. In Mike Bartlett’s play Bull, the character Isobel nicely expresses the sensibility in saying admiringly of a co-worker, “Not an inch of goodness. Sheer muscular wanker. He’s boiled down. He’s a piranha.” The figures of the manosphere — Andrew Tate most conspicuously — position themselves as expressing the logic of optimization. Jordan Peterson discusses it not so much with vainglory but as a fact. “It’s a very, very vicious statistic,” he says of Pareto distributions and the notion that the laws of mathematics themselves result in winners and losers. Pop culture has drifted towards this psychology of optimization. It is hard to imagine something like It’s A Wonderful Life being made today with its deep-dyed family values, its belief that material satisfaction (and reputation within one’s community) are the highest aims. What’s come to the fore is what I think of as “the sociopathic style” — it’s in the Martin Freeman character in Fargo, the Glen Powell character in Hit Man, it’s what Kendall Roy is trying to achieve throughout Succession but never quite manages, to get to a place of pure optimization, which is understood to be ruthless and sexuality-maximizing. In Hit Man, Gary Johnson, a teacher doubling as a pseudo-Hitman “Ron,” is perplexed to overhear a female colleague say, “I wouldn’t share a straw with Gary, but I would rip out my IUD for Ron” — and no matter that Gary is a nice guy and member of the community and Ron is (allegedly) a stone cold killer.

All of this converges, of course, in the figures of Trump and Musk, the totems of our time. “Too much and never enough” is the title of Mary Trump’s book on the Trump family, which seems apposite. The material satisfaction isn’t actually the point — it’s clear that there is no amount of gold-plating in Mar-a-Lago that will ever sate Trump’s appetite. The general sense with Musk is that he is deeply unhappy, in a bottomless pit of churning. (“If you buy a ticket to hell, it isn’t fair to blame hell,” he’s actually written about his own life.) What Musk has chosen to focus on instead is optimization — as in his 14 known children. The tech mogul Pavel Durov, the Telegram founder, has upped the ante by making use of sperm banks and has upwards of 100 children. There seems to be no question anywhere in here of material satisfaction; the biological imperative is absolute and the need for optimization limitless.

What I am describing isn’t exactly whining for the way things used to be. There is a part for me that accepts the precepts of Social Darwinism or evolutionary biology — that sees that as the truth and everything else as window-dressing. But I also think that it is very, very difficult to build any kind of harmonious society on that footing or to do so without recourse to real brutality. I’ve been watching a lot of action movies as part of research for a novel, and regular readers may note an unusual number of action movie references recently. In that spirit, let’s close with a quote from Winston Scott, the cravat-wearing, martini-sipping proprietor of the Intercontinental in John Wick. “Rules. Without them we live with the animals,” he says, and that seems to be where we find ourselves. A certain ethical floor — which was rooted above all else in the market logic of the Industrial Revolution — has disappeared. In our post-industrialized society, with its endless peacocking and fragmented communication, a different ethical base has taken its place, this one peeking its head around the long shadow of Judeo-Christian reproductive morality and repudiating it. The new ethic is optimization, and optimization only, and, as the evolutionary biologists themselves would point out, together with Winston Scott, it’s really not so different from the animals.

Correct analysis and also such a huge, incredible fail of culture. Also, leave animals out of it - they’re nowhere near as anti-rules, anti-collaborative, dystopian dysfunctional as we are, with our “Social Darwinism” “evolutionary biology” (can’t actually study it in humans, so it’s essentially a power narrative) excuses for bad acting. Add incredibly lax social enforcement whereby youth culture (the period where it matters most, because it’s most likely to be actionable) gets primed to very FUD about what is legitimate moral courage: taking such stands about sexual behaviour and, frankly, deviancy (the guy banking his sperm is, frankly, a deviant getting away with a lacuna in reproductive law). The stories we tell ourselves legitimize the worst behaviour.

And, you might find John Tainter's THE COLLAPSE OF COMPLEX SOCIETIES (Cambridge UP 1988), and some of Michael Taussig's later work of interest.

Thanks for taking all this on.

Douglas