It’s the third rail question in American politics, so absurd-sounding that you feel crazy even thinking it — is the president of the United States actually a Russian mole?

This idea has been planted in the national consciousness for a long-time, in The Manchurian Candidate, which was rooted in fears of North Korean brainwashing techniques, and then repeated in Homeland, which updated the same idea for the serenity and peace of mind that could be offered through jihad.

Both The Manchurian Candidate and Homeland were deeply silly programs, basically just escapism, but the idea that the president might be a foreign agent is, astonishingly enough, a very real proposition — and is, I would say, more probable than not.

For a long time, the primary data point for the accusation against Trump was a KGB major named Yuri Shvets, who left the organization in 1990, moved to America, and has for years been telling anyone who would listen his accusations about Trump. His charge forms the basis of reporting in both Craig Unger’s American Kompromat and Catherine Belton’s Putin’s People, both of which — moving from somewhat different directions — hypothesize essentially the same sequence of events. Recently, the accusation got a remarkable boost from Alnur Mussayev, who worked with the 6th department of the KGB and was later head of Kazakhstan’s security services, and in February wrote on Facebook, “The most important area of work of the 6th Department was the acquisition of spies and sources of information from among businessmen of capitalist countries. It was in that year [1987] that our Department recruited the 40-year-old businessman from the USA, Donald Trump, nicknamed ‘Krasnov.’”

The chain of events that the journalists who have followed Shvets’ lead put together runs something like this. Trump was of interest to Eastern European security services from as far back as 1977 when he married the Czech model Ivana Zelnickova — with Czech agents reading Ivana’s mail back home, interviewing her father about her life in the US, and filing reports on Trump that heavily detailed his financial operations. The Czech interest in Trump apparently extended to the Czechs sending a spy to meet with Trump in the late ‘80s amidst rumors that he might run for president. The more significant path to Trump, however, appears to have run through Semyon Kislin, who owned an electronics store in New York that specialized in a clientele of Soviet nomenklatura bringing Western electronics back home and who doubled as a “spotter agent” of the KGB. Kislin around 1980 sold a large number of televisions to Trump for one of his hotels, and this — Shvets and Unger believe — was the really fateful contact. “On the face of it the sale of television sets between Kislin and Trump had a few anomalies,” Unger writes. “The Hyatt Corporation had been a blue-chip outfit in the world of franchises for decades. Why was it getting television sets from a small Soviet shop like Joy-Lud instead of a reliable wholesaler? And those kinds of small electronic stores rarely extended credit. Why was Kislin doing such favors for Trump?” Shvets for his part says, “I’m 99% positive this is how [the KGB] started their file on Trump.”

There is no particular suggestion of a master plan, or real strategy, for Trump at this time, but the KGB’s interest in Trump coincided with a volta-face in the agency’s operations. In the ‘80s, the KGB largely gave up on recruiting ideologically-simpatico Westerners and started recruiting almost entirely on the basis of money. “The Russians were trying to recruit like crazy and were going after dozens and dozens of people,” said Unger in an interview. And meanwhile, as the ‘80s wore on and the Soviet Union teetered closer to collapse, the KGB plowed money into the West in what a 1990 memo by Gorbachev’s deputy general security called “an invisible economy” for the Communist Party.

As Catherine Belton writes, “In the beginning Trump’s business was probably no more than a convenient vehicle through which to funnel funds into the US.” Shvets emphasizes that, from the perspective of the KGB’s modus operandi at the time, Trump could hardly have been a better mark. “For the KGB, it was a charm offensive,” Shvets speculates. “They had collected a lot of information on his personality so they knew who he was personally. The feeling was that he was extremely vulnerable intellectually, and psychologically, and he was prone to flattery.”

The crux of the KGB’s recruitment of Trump was, almost certainly, his July, 1987 visit to Russia. There, Shvets continues to speculate, he was exposed to what Shvets calls “this bullshit” — a textbook attempt to butter up Trump by telling him how important he might be to the cause of international peace, and to the future political life of the US, and making particular use of Trump’s sudden interest in nuclear disarmament.

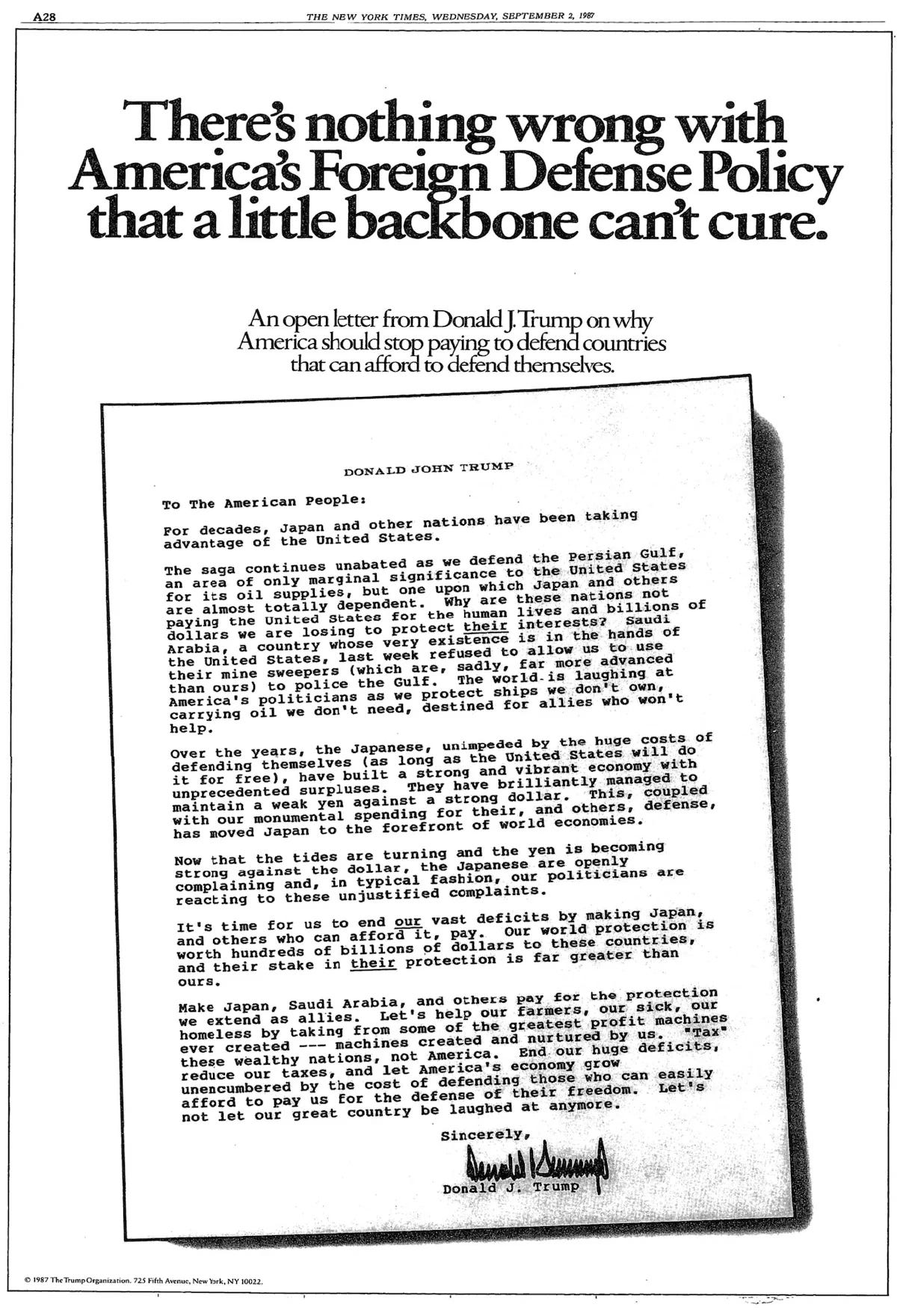

Shortly after his return to the US, Trump took out full page ads in The New York Times, Washington Post, and Boston Globe, at a cost of $95,000, to argue that the US should stop spending money defending Japan and the Persian Gulf. “The world is laughing at America’s politicians as we protect ships we don’t own, carrying oil we don’t need, destined for allies who won’t help,” the ads read. The ads were linked to Trump’s brief foray into the 1988 presidential race, when he paid for a poll, did some press, and held a campaign event in Portsmouth, New Hampshire before dropping the idea.

For the KGB at the time, claims Shvets, it was a real coup. Shvets wasn’t involved in the recruitment of Trump but recalls seeing a department circular bragging about the operation. “It was a big thing — to have three major American newspapers publish KGB sound bites,” he told Unger. “It was just silly,” he added in an interview with The Guardian. “It was hard to believe that somebody would publish it under his name and that it will impress real serious people in the west but it did and, finally, this guy became the president.”

Of course, the ads by themselves didn’t lead to much, but they represent a remarkable point of origin for Trump’s subsequent political career. “On this theme [US allies taking advantage of the US] and arguably this theme alone, Donald Trump has been entirely consistent for the past thirty-seven years,” writes George Mason professor

, who has studied this episode carefully.And the KGB’s cultivation of Trump continued to pay dividends long after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Unger calls it “the single most successful intelligence operation in history” — all the more remarkable given the shambolic character of so many of the KGB’s operations in the late ‘80s. Belton picks up much of the rest of the story in her discussion of how the KGB laundered money into the West in the ‘80s and into the ‘90s, an operation that fit hand-in-glove with Trump’s bankruptcies and his insatiable need for cash. “There was Trump and his financial problems — it was a solution that was very much on time,” Shvets told Belton. She continues, “The deals could not have been more serendipitous for Trump.”

The continuing relationship between Trump and Russian assets runs through the tangled stories of Trump’s bankruptcies and his sprawling real estate empire. The gist of it, though, is that the empire largely operated as a front for money-laundering. “When many of these [real estate] projects went belly-up after the financial crisis, it didn’t seem to matter much to any of [the investors],” Belton writes of 2008. It was all just a way to park money — and the money came from all over the CIS countries.

Belton’s book is actually not primarily about Trump; Trump is just a tack-on at the end. She writes about “the invisible economy,” the way that KGB money moved into Western bank accounts starting in the late ‘80s and how that money eventually turned itself around to become the “obschak,” or gangsters’ purse, that bankrolled the rise of Putin and the KGB revanchists to rule Russia. Trump was, for most of this period, just a peripheral part of these events.

But if we understand Trump as intimately connected with the “obschak,” and Russian money-laundering operations both during and after the fall of the Soviet Union, we understand much better his connection to Putin. “It is phenomenal how close [Putin and Trump] are to another when it comes to their conceptual approach to foreign policy,” Kremlin spokesman Dimitry Peskov crowed, with tongue-in-cheek incredulousness, in November, 2016. And that needn’t be such a surprise — they were coming from the same atmosphere, if not, essentially, the same operation. “Our boy can become president of the USA and we can engineer it,” the Russian-American mobster (and Russian intelligence asset) Felix Sater wrote in an eye-popping email to Michael Cohen in 2015. “I will get all of Putin’s team to buy in on this.”

Now, if Trump is really a Russian agent, the question is what that would mean exactly. Shvets surmises that he is a “trusted contact” — a particular type of operative who, as Unger puts it, “does favors for his Russian handler because of a personal relationship not because he is tasked.” That sort of agent would be different from a “straight penetration mole” or from the hapless Raymond Shaw of The Manchurian Candidate, acting as an automaton of a foreign power. It would mean that Russia has influence over Trump, if not control, and that he has a transactional allegiance to Russia that conflicts with his constitutional allegiance to the United States.

At the height of Russiagate, during the first term, it felt that the charges against Trump didn’t quite hang together — that certainly seemed to be the conclusion of Robert Mueller. The proof would have had to be in the pudding, and the pudding (I believed at the time) was whether Trump lifted sanctions against Russia. He didn’t do that — or at least didn’t try as hard as he might have — and that seemed to be the end of it.

But now I am much less sure. One of the features of Putinism is slow movement towards a distant object. Putin, let’s not forget, presented himself as a liberal democrat for the entirety of his first term and then into his second. The occupation of the Crimea occurred 14 years into his presidency, the invasion of Ukraine 22. Putin also runs an informal school for autocrats, of which Hungary’s Orbán, Belarus’ Lukashenko, Georgia’s Kavelashvili, Ukraine’s Yanukovych, Romania’s Georgescu, among others, are considered adepts. It is far from implausible that Trump in his first term was following Putin’s model — look after the economy and ensure an orderly succession. Putin for his part kept things in order for Trump — saving the invasion of Ukraine for Trump’s successor. One can only assume that the result of the 2020 election was a serious setback for Trump/Putin, but from the perspective of the long game all turned out to be in order. Putin held Ukraine at bay in the war of attrition, Trump won back the White House, and now US foreign policy is, frankly, what I sort of was expecting it to be when Trump took office in 2017 — the US withdrawing from alliances and commitments all around the world and with Russia the big winner. Trump is old but he has a viable successor in place in Vance and, without having to worry about his own election, he really can treat the next four years as his time to do whatever he wants. The proof is in the pudding and it was very hard to look at Trump’s performance with Zelensky in the White House or Trump’s immediate suspension of military aid to Ukraine and not see a situation where Putin gets everything he wants. Money, as we’ve seen, doesn’t explain all of it; ideology does as well, with Trump sharing fundamentals of the KGB revanchists’ worldview since as far back as the mid-1980s.

The basis of Putinism is a view of the state in which the ruler floats above the state structure — isn’t part of any particular social contract but has a hierarchy in place and is able to administer through that hierarchy, both monopolizing political power and immensely enriching himself, and having a grand old time about it all. All of that must sound very, very good to Trump, and, on top of his forty-odd years of contacts with Russian intelligence, he has abundant reasons to find himself in Putin’s camp. Putin has won, big time, and the United States, if not exactly part of Russia’s empire (it’s not quite as bad as that), is fast on its way to being Putinist.

To believe that Trump is NOT in an alliance with the Russians you’d have to believe that someone could offer him money and power and he’d… turn it down? Because… patriotism? Doesn’t fit. He has never even pretended to be a GOOD man. He adores Putin, openly. He pushes projects that undermine US power. He divides, which as Aesop taught us is the prerequisite to conquering.

This is an excellent summary of the arguments in favour, and I'm certainly edging towards this view. Your last paragraph is chilling - but, I fear, true. God help us all.