Well, it’s official. I’ve just finished my second Mormon-themed novel, which raises the question, ‘Sam, what the fuck is going on exactly?’ — since, I hasten to add, I have no belief in Mormonism, barely know any Mormons, and, if we’re being honest, regard it about equally as much practical joke as cogent theology.

My journey into Mormonism started, of all places, with a New York Times op-ed. Writing in 2012, the philosopher Simon Critchley described Mormonism as “strong poetry, from the same climate of Whitman, if not enjoying quite the same air quality.”

That was enough for me and led me to Harold Bloom’s The American Religion. Bloom was — let’s face it — mostly interested in the Mormons’ plural wife doctrine, but he believed also that Mormonism together with Baptism represented an authentically American religious belief system — the idea that “God loves the individual on an absolutely personal and indeed intimate basis” — and set down a challenge to American writers to write the Church’s “early story as the epic that it was,” adding that “nothing else in all of American history strikes me as material poetica equal to the early Mormons.”

And from Bloom I went to Fawn Brodie’s No Man Knows My History and from there never really left the enchantment of this history, which — Bloom is right — has everything in it. Brodie is herself an interesting person — she was raised as a devout Mormon in Utah, then apostatized, wrote No Man Knows My History, her biography of Joseph Smith, as a frontal assault on the received wisdom of standard Mormon history and in it tore Smith’s haloed reputation to shreds, but she also helped to create the image of a different, far-more fascinating Smith. I think it may be one of my favorite history books, and with much of its power coming from seeing Brodie’s disillusionment and reconciliation unfold as she writes. At one point I really got into the primary literature on the Saints’ Nauvoo period, but what I’m writing here is derived mostly from a rereading of Brodie.

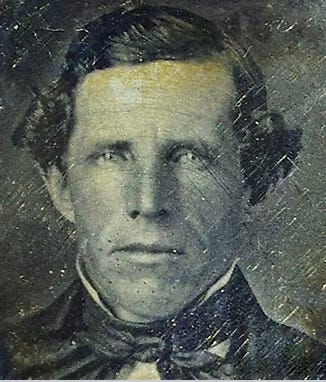

Smith was born in 1805 in Sharon, Vermont. In 1816, his family moved to Palmyra in Western New York. There were several critical points in his background. One was that Palmyra was in the “burned-over district,” the area of New York State that had been subject to an apparently never-ending succession of religious revivals, of ever-escalating fantasy and ambition. Then, that part of New York was filled with large, mysterious Indian burial mounds that seemed to belong to some lost civilization. Then, there was, in his family, “a certain non-conformity in thinking and action” — his grandfather had written a book, his mother would eventually write a book, his father had visionary dreams that would in time circulate directly into Mormon scripture. Smith’s youth is the section of Mormon history that is written by Mark Twain. Brodie describes him as “a likeable ne’er do well who was notorious for tall tales and necromantic arts and who spent his leisure leading bands of idlers in a search for buried treasure.” This treasure-hunting was fairly endless in Smith’s youth but there was a real urgency behind it — his family was in increasingly straitened circumstances, falling from land ownership to tenant farming — and Smith apparently had some ability in finding lost items by looking through a seer stone.

Then, in 1827, word spread that Joseph Smith had found a great treasure. The Angel Moroni revealed to him the location of golden plates on a farm near Manchester, New York. The story here gets very confused — and amusing — and has many different versions to it. But the critical event is that Smith relocated to Harmony, Pennsylvania, where he was now living with his new bride Emma Hale, and brought with him a heavy case that he said contained the plates, as well as a pair of magical spectacles — the Urim and Thummim — that he claimed gave him the ability to “translate” the plates without looking directly at them. He was newly married, his father-in-law had made him promise to give up treasure-hunting and devote himself to farming, but, as Brodie puts it, “Joseph was not meant to be a plodding farmer.”

For the better part of a year, Smith lived in Harmony. He threw a blanket on a rope to divide the room where he worked into two halves. He looked into his spectacles and dictated to one of several secretaries — Emma, Martin Harris, and Oliver Cowdery. Some days the revelations were slow in coming — Joseph found himself “spiritually blind” or went out and threw stones into the river — but he persisted and by mid-1829 had completed The Book of Mormon. There was a hitch, however. After he had completed 116 pages, Martin Harris prevailed on Smith to allow him to take the manuscript with him to Palmyra, but Harris’ wife, deeply skeptical of the whole project and of Smith’s hold on Harris, hid the pages and refused to divulge their location — and Smith, who certainly had a gift for adaptability, was forced to re-translate this section from a separate set of plates that had conveniently been left for him as a backup. Most books of divine revelation open with an account of, say, how the earth and heaven were created. The Book of Mormon — at least in the preface to the first edition — opens with an imprecation directed against the wife of Martin Harris and a curse in case she should reappear with the missing opening pages and try to point up the discrepancies in the accounts.

The Book of Mormon is, in a sense, the weak link in Mormon theology. Basically, it’s just not very good. Mark Twain called it “chloroform in print.” Bloom wrote that Smith was “a religious genius though only a mixed orator and an indifferent writer.” Smith himself, at a startling moment when he was at the height of his power in Nauvoo, insisted on burying the original manuscript under the cornerstone of the temple and was heard by a witness to remark, “I have had trouble enough with this thing.”

But in Smith’s dismissive words there was a real fondness. He was 21 when the book was first “revealed” to him. This was early days for American literature and Smith, certainly, was not from an educated background. As Brodie put it, writing of a somewhat disarming confession of Smith’s later in life for how the the book came to him, “What Smith was describing was simply his own alert, intuitive understanding and creative spirit.”

And this is where we start to get into the heart of what makes Smith’s brand of Mormonism so enthralling. It’s not about the baroque stories of Lamanites and Nephites, of Israelites voyaging to America in watertight boats, and Christ making a brief stop to preach to the Indians after his crucifixion. It’s what, in a later sermon, Smith — talking about himself — called “a rough stone rolling.” It was all creative principle and fecund imagination, and then in a very real and literal sense, Smith was — in the title of his that stuck most closely to him — a prophet. When, in the usual way of the humbug, he would answer his followers by saying that whatever they wished from him had yet to be revealed, he as often as not was speaking truthfully — what they wanted would occur in the fulness of time. As much as we can understand him as the exuberant young writer falling in love with his own first novel, we can understand him as well as the Harold Hill of divine revelation: the visitations of angels, the gifts of divine spectacles, were hokum, but what was very real was the fervent belief of Smith’s growing band of followers and that did, actually, work genuine miracles.

Which is not to say that scamming wasn’t also at the heart of it. Having revealed The Book of Mormon, Smith had the usual 23-year-old’s problem of finding a publisher. A prominent New York scholar had already dismissed in disgust a fragment of Smith’s revealed characters. A delegation sent to Toronto with the instructions that a man would be found there anxious to buy the book came back empty-handed. In the end, a divine revelation came to Joseph’s aid, ordering the ever-pliant Martin Harris to mortgage his farm to finance the cost of the printing.

What helped was the beginning of the series of communal miracles that would propel the Church forward. The group of Palmyra neighbors who were closest to Smith had been begging for glimpses of angels and golden plates. Finally, Smith led three of them into the woods. As Brodie writes, “They waited silently for a miracle. The summer breeze stirred the leaves above them, and a bird chirped loudly, but nothing happened.” Then, Harris concluded that his past sins — he may have been thinking of his failures as a husband — were to blame, and he absented himself. Shortly after he left, an angel promptly appeared to the witnesses and flipped through the leaves of the golden book. Then the witnesses went in search of Harris and the scene repeated itself, with Harris jumping up and shouting, “Tis enough. Mine eyes have beheld, mine eyes have seen.” Although, later in life, when questioned about this, Harris clarified, “I did not see the plates as I do that pencil-case, yet I saw them with the eye of faith.”

It’s that slippery zone between the eye that sees the pencil-case and the eye of faith in which Smith proved to be so adept at maneuvering. To understand the rise of Mormonism it’s necessary to understand the psychology of the time — which closely followed the Second Great Awakening. Harris, for instance, had followed an “erratic trail of religious enthusiasms, having been successively a Quaker, a Universalist, and a Restorationist.” The great break for the young Church was the acquisition of Sidney Rigdon and his band, who were a schismatic break from the popular Campbellite — i.e. Christian primitivist — movement in Ohio. Brodie is convincing that, in the hothouse atmosphere of the time, it was actually the intellectual appeal, and relative religious sobriety, of Mormonism that was its greatest strength. Smith, in the early days of the Church, found himself constantly curbing the excesses of his followers. Harris, for instance, had a bad habit of offering his toes to snakes and claiming apostolic victories on the occasions when they declined to bite him, and Campbellite meetings had a way of degenerating into adherents rolling on the floor out the entrance of the church and standing on stumps to address imaginary congregations in tongues.

The Church of Latter Day Saints would have five distinct phases. Palmyra, the first phase, was largely an affair of family and friends and a bit nepotistic in its affirmations of its sanctity. As Mark Twain — seeing that of the eight witnesses to Smith’s plates, five were Whitmers while the rest were Smiths — remarked, “I could not feel more at rest and satisfied if the entire Whitmer family had testified.” Kirtland, Ohio, the second phase, was very much about the influence of Rigdon and the fits-and-starts creation of a viable Church organization. This is one of the more mysterious periods of Mormonism, as it is an enigmatic chapter of American history. The preoccupations of this period — anti-Masonic parties, schisms of religious sects, bank charters and bank failures — would leave precious little imprint on the cultural psyche; and same goes, in a sense, for the Church in Kirtland. Smith, at the end of the Kirtland period, would describe it as “seven long years of servitude, persecution, and affliction in the hands of our enemies.” The intellectual productions of this period — the Book of Abraham with its racist doctrine of the ‘curse of Ham’ — would be some of the more embarrassing legacies of Smith’s theological record. The most enduring Mormon revelation comes from Kirtland as well, although it’s not actually even a revelation. Smith had been profligate with revelations at this time — many had been “frankly financial” — but the revelation to abstain from alcohol and tobacco was made with uncharacteristic mildness as “good counsel” and, according to Brigham Young’s later testimony, was in direct response to Emma’s growing exasperation with Joseph’s friends visiting him on the second floor of their house and then spitting tobacco juice on the floor.

The reasons for the collapse of Kirtland were, primarily, financial. As part of the explosion of banks in the 1830s, Smith had launched a bank in Kirtland, although, as one witness discerned, the specie rested on “boxes filled with sand, lead, old iron, stone, and combustibles but with a top layer of silver coins” — and, when the bank collapsed, a few months before the general banking crisis of 1837, the Church as a whole disembarked to join the already-existent colony in Far West, Missouri.

This is the part of Mormon history that’s directed by John Ford, and it’s Joseph at his finest. As luck would have it, the forbidding prairie turned out to be precisely where the Garden of Eden had been and a whole series of Biblical scenes enacted. And the fledgling Mormon community took heart from the Prophet’s presence and these Biblical antecedents to, with industry, create a viable community — which brought them into endless clashes with gentile settlers. A full-fledged war broke out in 1838, with Missouri governor Lilburn Boggs issuing an extermination order for the Mormons and the Missourians enthusiastically following up on it. Smith had organized a small Mormon army, and he was an inspiring leader. Finding a group of his soldiers looking disconsolate shortly before an expected battle, he challenged them to wrestling matches and threw them all. When the fanatical Rigdon showed up with a sword accusing the men of breaking the Sabbath, Smith knocked the sword from his hand and declaimed, “Go in boys and have your fun. You shall never have it to say that I got you in any trouble I did not get you out of.”

But the Mormons were badly outnumbered by the Missourians. While Smith played his part as military leader to the hilt, he quietly dispatched an emissary to “beg like a dog for peace.” Unlike many another scoundrel, he had it in him to put his followers first, and, before the decisive attack on Far West, he called his men together and declared, “You have been willing to die for me for the sake of the Kingdom of Heaven, and that is offering enough in the sight of God” — and then he surrendered himself to the Missourians, fully expecting that he would be shot at dawn.

If Smith was somewhat light-fingered in his leadership of the Church and a hit-and-miss theologian, he made an admirable prisoner. Later in life, remembering how Smith conducted himself on the eve of his expected execution, fellow prisoner Parley Pratt wrote, “Dignity and majesty have I seen but once as it stood in chains at midnight in a dungeon in an obscure village in Missouri.” In the end, though, the consciences of the Missourians caught up with them. After several days of depredations in Far West, the Missourians permitted the Mormons to flee across state lines to Illinois. Smith’s expected execution turned into long court delays and eventually he was able to bribe a jailer and make his escape.

Wonderful history and so glad it's only part one! I'll admit that growing up I was actively prejudiced toward a Mormon kid who lived a block away, but after the past decade of broad-based societal derangements I no longer perceive Mormons so much as "others" as an idiosyncratic sect very deep in the American grain.

Sam, interesting read. It was curious to see it put this way. As a Latter-day Saint (we don’t really go by Mormons anymore), I’d be happy to chat if you have any questions about the lived experience of the faith today.