Dear Friends,

I’m continuing my Curator thread from last week. This is a round-up and discussion of the more interesting culture articles I’ve come across recently.

Best,

Sam

AI AND TECHNO-FEUDALISM

So we’re a year and a half into AI and the world hasn’t ended, the killer robots aren’t prowling around, everything kind of looks as it always did.

But I am anti when it comes to AI and the last year-and-a-half has aligned with my basic inclinations towards it. It’s not so much that AI has wholesale transformed the society but that it has integrated itself into so many functions of our life that it’s become increasingly impossible for us to do without it.

Neural machine translation functions allow for staggeringly efficient translations between every conceivable language. My students deploy AI habitually if they want, say, an image to accompany an assignment. Whole new fields of endeavor suddenly come into people’s sights — people who like music but didn’t learn to play an instrument can suddenly generate music; same goes for art; same goes for writing. The technique is taken care of by a machine as opposed to some hard-earned skill and people are able to focus entirely on the creative side of it.

That’s irresistible and socially transformative. And it means that we are poised for an immense number of feel-good stories. People who never made it into Hollywood will — sitting in their parents’ basements and executing AI commands — soon be able to make full-fledged Hollywood-style movies, and often using the digital likeness of long-dead actors. The developing world has a chance to catch up to first-world countries in all kinds of cultural and professional domains — with use of AI giving people the opportunity to overcome barriers (infrastructural, linguistic, etc) that would have been insuperable a few years ago.

But at the same time, AI is making a mockery of work, of so much that we consider to be our intrinsic value. I’ve been trying to be philosophical about this. My argument has been that AI is, essentially, the culmination of five hundred years of the Baconian project. The West privileged ‘science’ and the analytic, reasoning sides of ourselves to such an extent that we not only became that but created an entirely new kind of consciousness that was only that. In a modern, Western work environment, to call somebody a “machine” is a major compliment. But, with the advent of AI, those hard-working, hyper-focused machines — all the graphic designers, translators, customer service operators, quants, techs, etc — become almost entirely redundant. There’s an opportunity somewhere in here to shift away from the Baconian project, to privilege EQ and different, more spiritual aspects of ourselves. And AI is a useful tool in showing us what we are not. Anything that AI can do becomes de facto not the ‘me myself,’ not the essential, idiosyncratic parts of us — and so, in our search for meaning and identity, we lean into everything that it is not the machine, not AI.

But philosophy takes you only so far. In the meantime, AI is starting to cut an immense swathe through the white-collar workforce. Good luck getting a customer support person as opposed to a friendly chatbot. And the cost-cutting possibilities of AI are so immense that any boss will sooner or later get rid of just about anybody offering dispensable, value-add services. What’s worst about this is that — like the idiot townspeople in the early scenes of a sci-fi flick — companies have been actively putting out to call to ‘integrate AI’ into their operations, to ‘welcome AI.’ As agriculture and a traditional way of life was cheerfully destroyed in the 19th century, we are eviscerating the conditions of our own white-collar existence. It probably is, to some extent, inevitable, but, at the very least, we can have a tragic sense about it and not welcome AI too enthusiastically.

For myself, I’m trying to do a soft boycott of AI. I’m not downloading ChatGPT or Dall-E or their successors. I don’t look at the AI answer that comes up at the top of the screen when I do a web search. But I also know that that’s a very arbitrary line in the sand. The Apple/Google products of the 2000s and 2010s already corroded so many of my natural brain functions: Maps has almost entirely eliminated my ability to figure out directions, Notes has carved out much of my memory (a seven-digit phone number is almost impossible now), Translate has cut deeply into my incentives for learning foreign languages. I have accommodated myself to all of those transitions. AI is, in some important sense, no different. But I just really don’t want to be part of it.

Meanwhile, the analogies to the pre-Baconian world are being spelled out in different and unsettling ways. The ever-perplexing Yanis Varoufakis, “libertarian Marxist” and very briefly Greece’s Finance Minister, has an interesting argument in which he contends that the new tech sector — “cloud capital” — represents an entirely different economic form, which supplants capitalism itself.

Varoufakis makes his arguments by analogy to the Middle Ages. There, the feudal order is based on value that is produced off the land and then a dominant social class acts as rentiers, owning the land and forcing those who create value from the land to pass the profits up the vertical social chain. Capitalism emerges as a new force adjacent to and supplanting that system, generating new modes of wealth and producing entirely new sorts of products. “Capitalism overthrew feudalism, but it needed the feudal sector to continue producing food because otherwise we would all have died,” said Varoufakis in an interview with Jacobin. “That’s why I’m saying that capital was parasitic on the feudal agricultural sector. So, it’s not that one dies and the other lives. What happens is that capital takes over the hegemony of the system, but it is parasitic on the previous system.”

More or less the same thing is happening with ‘cloud capital,’ Varoufakis claims. Capitalism continues to produce products and value, but the real profit comes from monopolistic control of online spaces — with the tech giants acting as rentiers, with regular people participating in that space, having their exchange of goods and services, but with the brokerage fees skimmed off and sent to the “cloudalists.”

For Varoufakis, this is not just business-as-usual. It represents a dramatically different economic system. And the atavistic language that has been seeping into our vocabulary — ‘tech overlord,’ ‘digital serf,’ ‘fiefdom,’ etc — is all very applicable. It is techno-feudalism. And it produces a deeply distorted system in which value is almost wholly disconnected from profit.

For Varoufakis, what is useful about this is that the old distinctions between labor and capital break down. Everybody is being supplanted by the new predator. And that means that, in theory, some level of collective resistance is more possible.

WHAT’S BECOME OF HIGH CULTURE?

The perfidious influence of cloud capital is nowhere so clear as in high culture — or what remains of it.

Aaron Timms has a terrific article in The New Republic riffing off Kyle Chayka’s Filterworld. The argument here is that the demolition of what used to be considered high culture occurred in several distinct phases. The market got there first, turning art into a saleable commodity, demanding a ceaseless repetition of what was already fashionable. And then the algorithms “managed and extended that,” with a marketplace constructed for success (or ‘virality’) and with new work slotted in according to its ability to meet the digital footprint that is allocated for it.

As Timms writes:

For an artistic work to achieve commercial success, it must be engineered to maximize engagement on a digital platform, which leads to the creation of lots of things that look and sound very similar….The rule of culture in Filterworld is: Go viral or die.

Timms quotes the New York Times critic Jason Farago (there are a lot of people making this same point) as saying, “When I was younger, I looked at cultural works as if they were posts on a timeline, moving forward from Manet year by year. Now I find myself adrift in an eddy of cultural signs, where everything just floats, and I can only tell time on my phone.”

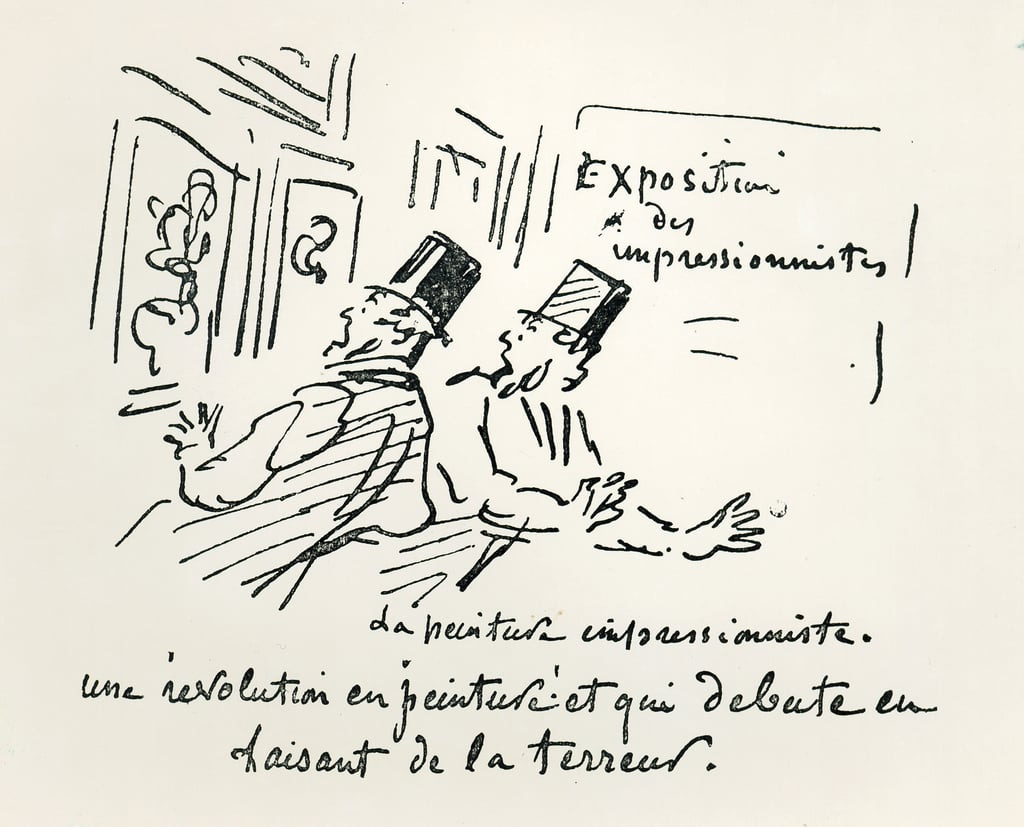

And, as curmudgeonly as this sounds, there is some evident truth to it. The older model of artistic production had to do with a push-and-pull within the consciousness of society as a whole. The struggle between the impressionists and classicists (for instance) was a real battle about the direction and identity of the society — artists were arguing in their work about what the values of the society should be. And for Manet — or whoever else — to emerge as a ‘post on a timeline’ meant that they had triumphed in some dialectical battle about what the society (or the cultural center of the society) wanted to be. Once the market, and then the platforms and the algorithms, become too dominant, however — become the air we breathe — then that push-and-pull is largely meaningless. Chayka, in his insatiable labeling, calls it “AirSpace” or “Filterworld.” The major questions have already been settled — success is already defined as number of likes, clicks, amount of royalties generated — and ‘content’ turns out to be grist for the mill.

For ‘high culture’ to reemerge in any meaningful way means deserting at the very least the more restrictive outlets of ‘Filterworld.’ The Impressionists had their own show, the Modernists their own presses. Whether the crowds come is a completely different story — it’s entirely possible that ‘high culture’ will never again find itself situated at the cultural center. But for high culture to exist, there does have to be some repudiation of Filterworld — some recognition that participation in Filterworld always involves a straightjacketing of one’s aesthetics and that for artists to actually be themselves and say what they want to say they do need to carve out space that’s removed from the algorithms, the clicks, and from mainstream culture itself.

PRE-MODERN WORLD ORDERS

If there’s a theme today it’s that ‘progress’ is not really linear or inevitable. There is a great tendency among the technofuturists (and it’s baked deep into the Baconian vision of our civilization) to believe exactly in this — that technology and innovation are always ascendant, that the straight line can always be charted from less knowledge and intelligence to more, that utility is always optimizing itself.

But Silicon Valley itself may be more a sliver than we realize. (It occurred to me to my surprise the other day that Europe has no equivalent — Silicon Valley and virtually the entirety of our ‘inalienable’ progress is an extension of a fairly small group of people and narrow constellation of circumstances in the US and now China.) Governments could regulate it if they wanted to. The vision of ‘inalienable progress’ really has most to do with the desires of the people who are pushing it, and to some extent their guiding philosophy.

It’s all a bit more fragile and contingent than it appears. And history really is better understood as a series of mutations — often, a very few driven individuals reshaping the world around them; sometimes one philosophical system pushing out another — more than it is as a techno-futurist linearity.

I was thinking about this more acutely as a result of a really excellent article in Aeon by Ayse Zarakol on the Asian world order. Zarakol, a professor at Cambridge, holds that a Eurocentrism (and Baconianism) really does excessively undergird our understanding of history. The international order is meant to have emerged from around the 17th century, with a series of Western nation-states gradually pushing out atavistic political systems across the world and creating, ultimately, a liberal international system.

What’s missing in that analysis is how strong the various pre-modern Asian empires were — Mongol, Timurid, Ottoman, etc. They weren’t marauding barbarians. They had advanced statecraft and created something very like an international order — albeit along ethical and philosophical lines that often were very different from that of their European successors.

As Zarakol writes:

We must scrap the traditional narrative lurking in the background of the Westphalian origin myth of international relations, ie, the narrative of an ascendant European order in the 16th century with non-European hangers-on looking in, such as the Ottomans on its periphery (or the Russians). The real picture is just the opposite.

The really critical difference between the Asian world orders and their later European counterparts is that there is an entirely different concept of sovereignty. The European order that emerged emphasized social contract theory (the state as an interlocking series of contracts) and international affairs as a set of treaties and covenants (maybe coercive but that’s another story). The Asian orders viewed a ruler as obtaining their mandate from heaven and with the rightness of their rule demonstrated through heaven’s favor and particularly through military success. As Zarakol writes:

The claim to greatness was based on the claim of the rulers from these houses to be sahibkıran, universal sovereigns marked by signs from the heavens, living in the end of days, delivering on millennial expectations.

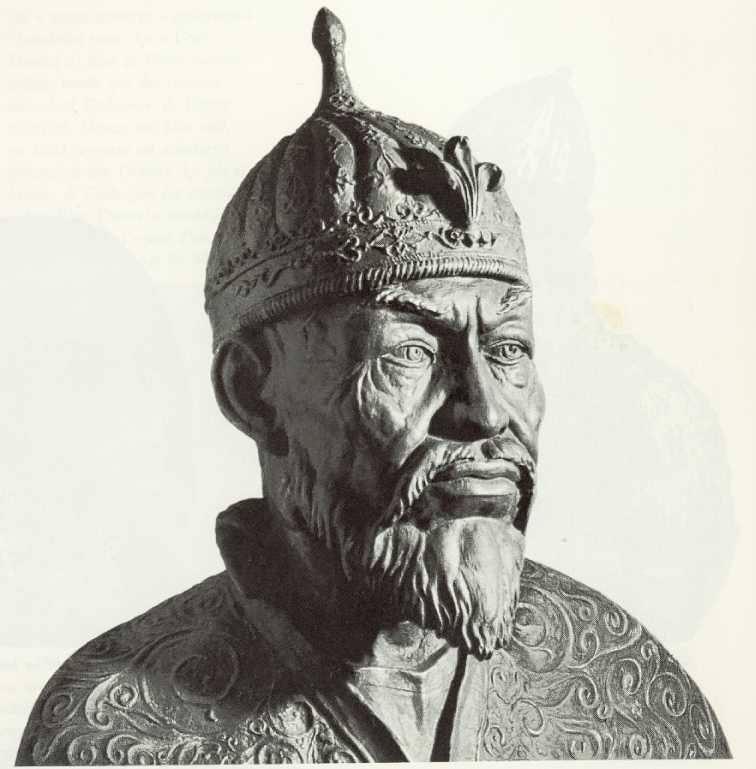

Recently, I visited the tomb of Tamerlane in Samarkand and had a strong sense of what Zarakol is talking about. Tamerlane really was a bloodthirsty and, in modern terms, genocidal conqueror. He is estimated to have killed around 17 million people — around 5% of the world’s population. His career was a tireless and apparently random series of conquests — campaigns in Russia, India, Syria, etc, and much of it to little discernible end: he couldn’t keep a great deal of what he had conquered and his empire started to disintegrate immediately after his death. It was a very unsettling feeling for me to be at his tomb — it felt like being at Hitler’s mausoleum or something, assuming that Hitler had lived to a ripe old age. But, nearby, a group of people were holding out their hands for blessing — Tamerlane was something like a patron saint here, and a key figure in Uzbek national conception.

That idea is extended further in a work like Marie Favereau’s The Horde or the general genre of Mongol revisionism. The point is that the Pax Mongolica that followed Genghis Khan’s conquests and prevailed across Eurasia wasn’t some kind of accident — it was an achievement of statecraft, although hard for Westerners to recognize as such given both cultural biases and the Mongols’ high body count.

And this sort of Mongol revisionism — which I had always taken to be something of a frivolous academic exercise — has a real significance. It’s not trying to morally excuse the conquests of Genghis Khan and Tamerlane — that’s irrelevant — but contends that there were other international orders founded on very different political philosophies that were nonetheless viable from the perspective of statecraft. Which means that there can be different international systems that emerge again.

As Zarakol writes, “One of the greatest benefits of moving beyond Eurocentrism and thus having more examples outside of European history to think with about our present challenges is that such examples expand our imagination as to what is possible.”

We don’t have to be entirely stuck with what’s around us.

https://iweothers.substack.com/p/the-necropolises-of-ai

https://iweothers.substack.com/p/the-return-of-the-future-to-its-past