Dear Friends,

I’m sharing ‘New(ish) Books’ for the week. This is a discussion of one fiction and one non-fiction work — with the format a bit different than a typical ‘review.’ Much of the real purpose of this Substack, by the way, is about self-work. I noticed a couple of years ago that I was reading much less than I used to — and rarely getting to the end of books. This feature is in large part a concerted effort to compel myself — and hopefully you too!— to read more. At Mary Tabor takes on the critics over HBO’s Scenes From a Marriage.

Best,

Sam

ANDREW MARTIN’s Cool For America (2020)

Martin is a writer I have a lot of sympathy for. He’s my generation — millennial — and he’s an avowed practitioner of closely-observed realism, a style that seems to be falling into abeyance as more and more writers move into some fantastical or metaphorical space. And Martin can really write. His sentence-to-sentence writing is as clean and original as anything I’ve come across recently. His dialogue, in particular, is where his talent shines — so spiky and funny.

So, as good as it is, why does Cool For America somehow seem to be less than the sum of its parts? Well, maybe because that’s the nature of a short story collection — which, almost by definition, is all parts. Or maybe because it’s not always so clear what Martin is saying — I have the sense that he falls a little bit in love with his own voice, that the stories can be more of an exercise in craft and exquisite writing than in actually following the journey of his characters. Or maybe because the stakes are never all that high. It can feel like Martin read Denis Johnson at too-impressionable an age: whenever he can, he really ratchets up the narcotics intake, but that never feels completely convincing — and, most of the time, all that’s really at stake is awkwardness or a character feeling even a bit more adrift than they did at the start of the story. “It was incredible, she concluded, the number of ways one could be condescended to,” Leslie thinks in the collection’s final story — and that, not-so-satisfactorily, seems to be what Martin mostly has to say.

But there are a few themes that, quietly enough, emerge out of the collection. There’s the divide between the East Coast and Montana — the way that his characters feel lost in New York City but completely unmoored in Montana, with so little contact to the culture-at-large that they start to sense something dissolving in their identity, some coherence getting lost. The strongest stories in the collection are about these unlikely-to-work relationships and these peculiar small-town characters — the bookish East Coaster who ends up in a relationship in Missoula with a woman twice his age; the boy vet who’s maybe a brooding genius and almost definitely a sociopath. The stranger and more off-kilter the stories, the better they tend to be. And the Missoula characters — Chloe in ‘Cool for America,’ Kate in ‘Short Swoop, Long Line,’ Cameron in ‘The Boy Vet’ — have a haunting power to them, a sense that they are very, very full people who are glimpsed in only a highly foreshortened way. Chloe in particular is one of the better woman-written-by-a-man characters I know of in contemporary fiction. Her style and her humor come across in just a few winning lines of dialogue — “Chloe leaned across the couch and rubbed my head. ‘Aw, it wishes I was single,’ she said” — but, as the narrator becomes entangled with her, the thought crosses his mind that “I did not know or understand this woman,” which is a fair summation of everything in the East Coast-Missoula cultural exchange.

And the real winning theme, somewhat surprisingly, is an elegiac sensibility about millennials. “The reading group had begun meeting in January, two months after the [2010] midterm elections that had, as they could not yet know, swept Democrats out of power for the almost next-decade,” Martin writes — and this bald statement of political fact is actually very resonant. His characters have conditioned themselves for a life of ease and ironic detachment — the problems that they seem to be dealing with are things like wondering if a board game from the 1990s is “nostalgic kitsch yet,” like trying to “achieve the perfect balance of intelligence and spontaneity” in the punctuation of text messages — but, faster than seems really fair, that whole way of life collapses. Throughout Cool For America, the characters find themselves flung, without being ready for it, into more difficult, darker emotions. A character is left alone with a woman with the admonition “be good” and wonders suddenly if this is “an Arthurian morality test.” A character plans a bantering evening with her partner, and, being abruptly reminded of a past infidelity, “cancels her smile and sits up straight,” prepared now for many hours of recriminations. A laidback character, dealing seriously for the first time with the possibility that she might become a failure, reflects, “She knew, from talking to other losers, that imagining you were talented was the first step to a life of self-pity and disappointment.” A character embarking on an affair thinks it’s likely “something to be brought up in a drunken bout of sexual trivia someday” and then — encountering BDSM and a highly mature sexual partner — discovers it to be “a strenuous educational night significantly more demanding than his previous sexual encounters.”

The writer Martin most reminds me of is Michael Weller who, in his Moonchildren plays, documented the growing pains of the ‘60s generation, suddenly getting older and the world not changing in any of the ways that they expected it to. In Cool For America, these sorts of cultural and generational markers are a source of obsession for all of Martin’s characters. “Culturally, drinking seems kind of over, you know?” a 22-year-old says to a woman in her late 20s — who is horrified to hear that piece of news. “I left the theater in a haze of discontent,” a character reflects at the end of an action movie — feeling that movies have structured themselves completely differently from a few years earlier, that the familiar signposts have all shifted. This set of reflections would seem to be the height of trivia — the millennials went through a far less tumultuous period than the ‘moonchildren’ did; and Martin’s characters themselves are often at pains to insist on the negligibility of their own lives — but it is a bracing discovery nonetheless, that the world one thought one was in just doesn’t exist anymore.

And that sense of elegy for the spoiled, ironic millennials produces spurts of really wonderful, unexpected writing. “I counted each hour she stayed alive as a major achievement, a line on karmic CV,” a character says of owning a pet; or “It was all so much natural wallpaper, a late nineties screen saver,” as another character reflects of a gorgeous Western landscape. The affect is snarky, important questions rerouted through pop culture references, the feeling is of all of existence — God’s green earth, karma, etc — being made cozy and super-convenient. It may have been a silly way to look at the world but that was the mindset for a generation that was promised a lot, and — as Martin’s characters flounder, get older, come across the hard realities of personal finances and the job and dating market — their willed vapidity reads less as spoiled and more as early, faltering attempts to deal with tragedy.

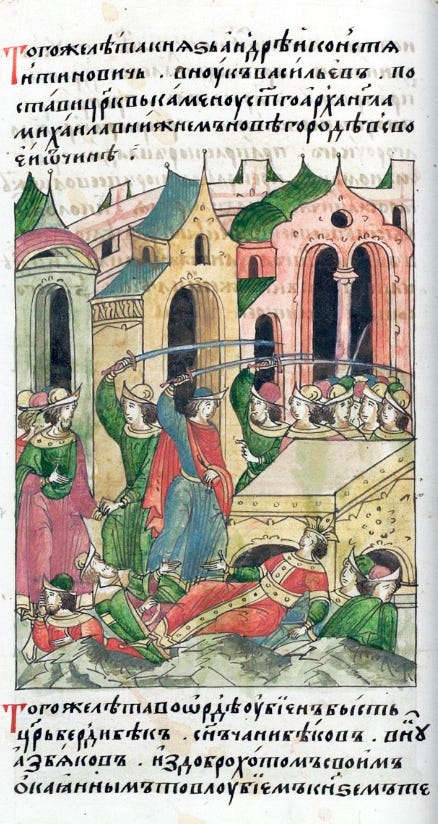

MARIE FAVEREAU’s The Horde: How The Mongols Changed The World (2021)

I’ve been eyeing this book for a while on the table at Book Culture, although not for any real reason — I think I was amused by the theme of Mongol revisionism that’s emerged from contemporary scholarship: treating Genghis Khan and his descendants less as a bloodthirsty scourge and more as basically reasonable steppe nomads with a somewhat-higher-than-usual violence quotient.

And by the time I got to the end of Favereau’s introduction I was sold. Her essential point is that Mongol rule in Central Asia lasted for the better part of three centuries, that it promoted an extended period of prosperity — what Favereau calls an “unprecedented commercial boom” — and that these developments were not accidental but resulted from the highly effective administrative systems of the Mongol regimes. Left to one side — and Favereau is impressively amoral about this — is the tremendous violence involved in subjugating the domains of the Mongol imperium, and the focus is on, as she writes, “treating the horde as an effective case of empire building.” On those terms, Favereau’s thesis is almost incontestable. The Mongols were, as she puts it, “expert administrators,” who provided a security system through the monopolization of force, were skilled and dogged tax collectors who largely used their tax revenues to facilitate commerce — “for the [Mongols], tribute was a transaction, with investments yielding productivity yielding tax revenue, enabling further investments,” Favereau writes — were highly mobile, highly adaptable, past masters in the art of diplomacy, and had the imperial gift for tolerating disparate religions and customs so long as basic fealty to the system was acknowledged and the wheels of commerce kept humming.

It has been very difficult to see the Mongol Empire in these terms for several reasons — the extreme violence of Chinggis Khan’s initial conquest; the dearth of written records from the Mongols’ perspective, particularly in the western part of the empire, which is Favereau’s focus; the extended centuries-long propaganda campaign against the Mongols by Russian writers; and certain ingrained biases by ‘sedentary’ peoples against nomads. It was this bias, the tendency to underestimate the versatility and ingenuity of nomads, that led, in the first place, to sedentary empires’ catastrophic failures to resist Chinggis Khan’s invasions; and it persists in scholarship. As Favereau writes, “The tale of the Horde remains as though behind a veil” — as powerful and as influential as the Mongol regimes were, there is something about them that eludes the grasp of sedentary peoples.

Much of the key to understanding the Mongols is, as Favereau demonstrates, a simple matter of inverting certain categories in one’s understanding. The Mongols had more than disproven the old Chinese proverb that ‘an empire cannot be ruled on horseback’ — that was exactly what the Mongols did and did for centuries. The ‘keshig’ becomes the key institution — a kind of mobile court, able to establish itself anywhere and to create consensus and authority; and, in turn, the keshig facilitates the ‘quriltai,’ the meetings that, to a surprising extent, ensured a line of succession and unity of decision-making within the Mongol domains. As Favereau writes, the tendency is to “see consensus building and moderation as the exclusive province of the civilized and modern, leaving the Mongols as mere pirates of the land,” but the Mongols were better diplomats and better at consensus building than their rivals, and, in religious and cultural matters, more tolerant. From the outside, their movements looked haphazard and their achievements ephemeral, but much of that was a simple matter in their conceiving of their territory in more flexible, more ‘nomadic’ terms than sedentary people would have; in their habit of “building their cities more of earth than stone”; and in their care to always maintain freedom of movement. Their facility with tactical retreats, their willingness to adapt to local customs — most conspicuously in the Golden Horde and Ilkhanid embrace of Islam in the 13th century — all led to confusion. Outsiders often assumed that the Mongols were retreating or were being tamed by a sedentary lifestyle when in fact no such thing was occurring. Favereau highlights in particular the “terrifying and perverse diplomacy” they conducted in advance of sieges — sending contradictory messages to a besieged city, with the idea both of bewildering the defenders and of provoking some intemperate response, which would give the Mongols the sense of being wronged that was the usual prerequisite for a military action. Even the Mongol habit of fighting their campaigns in the wintertime was an almost perfect inversion of the practices of sedentary peoples and resulted in tremendous confusion for their adversaries.

Seeing “the Horde on its own terms,” as Favereau does, means, ultimately, perceiving the Mongols as fundamentally rational. The term ‘horde,’ as it has come down to us, refers of course to an unruly mob, but the Mongol ‘orda,’ the source of the word, describes a tightly-organized structure, able to move hundreds of miles with ease, to simultaneously conduct campaigns all across Asia, and to maintain administrative coherence throughout. Part of it is that the Mongols seem to have been — in very simple terms — astonishingly impressive people, capable of acts of skill that dizzied their rivals.

Outsiders noted their horsemanship — their skills in breeding and training as well as riding, with their horses able to forage for grass underneath snow and to survive in unusually harsh conditions — and noted their ability to ford rivers in places that even experienced river people deemed impassable. Contemporary chroniclers were fascinated by their women’s ability to “make everything.” Favereau writes that their meticulously organized camps were viewed as being “the safest places on earth.”

That impressiveness extends to the macro-world of empire-building — the Mongols recognizing always the importance of a reliable taxation system; prioritizing commerce; treating the craftsmen of conquered peoples as a valuable commodity. Particularly intriguing to me is the Tengri concept of ‘sulde’ — “the vital force that gave warriors majesty, male strength, and good fortune.” In some sense, then, empire-building becomes the highest spiritual activity — and everything described in Favereau’s text, the battlefield ferocity, the diplomatic cunning, the attention to administration, seems to flow from ‘sulde.’

As engaging as the thesis of The Horde is, it’s not exactly a book I would widely recommend. Most of it is ethnography — a diligent scholarly attempt, from coins, commercial records, archeological finds, to understand how Mongol administration and commerce worked. The main points can be digested from the introduction and epilogue. The rest of it really is a welter of events from a very confusing time — the Mongols settling down to rule over their vast empire and dealing with challenges from virtually every direction. What’s missing — not that I think is the fault of Favereau — is a sense really of what the Mongols’ mental orientation was like. Sulde is a helpful concept, as is their abiding materiality. Favereau claims that Chinggis Khan wasn’t exactly aiming at world conquest, as is usually supposed, but at forcing the submission of the steppe nomads — and did so well that he moved into the domains of sedentary peoples as well. But, given the general dearth of written records, it becomes difficult to form a mental picture of, for instance, Berke Khan, who led the momentous conversion to Islam in the mid-13th century, or of Birdibek Khan, who shocked contemporaries by taking the usual succession purge to new heights, murdering all twelve of his brothers and his own son.

From a wider vantage-point, what The Horde mainly serves as— other than a useful handbook for empire-building — is as a companion piece to Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn of Everything. Together, they participate in a new movement — the nomad history of the world; a perspective that the biases of sedentary people (above all their near-monopolization of written records) have prevented us from understanding the pivotal historical role played by nomads. Graeber and Wengrow are writing about ‘pre-history’ and tend to be speculative. Favereau, though, is dealing with a fairly recent nomadic efflorescence and is able to contend, very persuasively, that the Mongols were not (as they’re usually seen) a sort of atavistic anomaly, as much of a scourge to civilization as the Black Plague, but represented a civilization of a different sort and were more integrated with the evolution of sedentary societies than those societies afterwards liked to recall. As Favereau writes, “The Horde changed the world. They introduced the vitality and ingenuity of nomads into sedentary peoples, with lasting consequences.”

This was nowhere more the case than in the history of Russia. Standard Russian history tends to create a binary between the successive regimes Kyiv-Novgorod-Moscow and what came to be referred to as the ‘Tatar yoke,’ but Favereau claims, convincingly, that this is revisionism. The Mongols decisively broke Kyiv, were engaged in complex power plays with Novgorod — with Alexander Nevsky preferring to maintain subordinate relations to the Horde while fighting fiercely against Swedes and Germans — and, as Favereau writes, “in many ways created Moscow’s authority.” Essentially, it was the Mongols — specifically the ‘Jochids’ aka the ‘Khanate of the Golden Horde’ — that created the Russian Empire; a system of governance that Muscovy inherited as much as built. “Moscow was an expanding state that looked to the Horde as a source of its legitimacy and power,” Favereau writes. This is far from the standard Russian view, but, seen in that light, some aspects of the modern-day Russian psyche make more sense. Later Russian chroniclers tended to emphasize the Western origins of Russia, to focus on the links with Rus, with Byzantium, and with Europe, and to treat Moscow’s expansion as an eastward push. Buried in that narrative is the long period in which the Russian princes were more or less enthusiastic tribute-collectors for the Jochids, using Jochid support as a tool in their rivalries with each other, and during which the Jochids “favored Moscow,” redistributing power away from Kyiv and Byzantium and towards the principalities. That idea appears in somewhat subterranean form in the Russian ‘Slavophil’ tendency, in Aleksandr Dugin’s theory of ‘Eurasianism,’ in the treatment of the steppe in a work like Viktor Pelevin’s Buddha’s Little Finger — and, in some sense, culminates in Putin’s severing of ties with the West. The Russian sensibility isn’t really so dissociated from the Mongol past as the pro-Western chroniclers sometimes like to think. The roots of the empire were laid down by the Horde — in extractive tribute, extreme violence, the Tengri spirit of ‘sulde.’ Pelevin refers to this as the ‘steppe wind’ and it is — as Favereau demonstrates — a ruling sensibility as much as some sort of primordial anarchy.

The term ‘Pax Mongolica’ that’s used to refer to the ‘unprecedented’ prosperity of the late 13th century made me think, inevitably, of the contemporary ‘Pax Americana.’ There are a few surprising parallels. There’s the similar emphasis on the ‘disproportionate’ monopolization of lethal force and the ways in which force is understood to be a lubricant for trade. After the initial conquest, the Mongols were, to a surprising extent, ruling through ‘soft power,’ allowing their vassals to exercise autonomy but insisting on open markets and on tribute when asked for. The connection with America isn’t worth stressing too much — this may simply be the structure of a successful empire — but, again, the understanding is that the Mongols aren’t quite so distant from us as we sometimes think them to be. They were, in their own way, shapers of the modern world. And their rule, staggeringly vast and surprisingly enduring, is, in its amoral way, a kind of crystalline glimpse of the essential nature of empire.

The Mongol book sounds interesting. Would be a good follow-up once I read John Man's Genghis Khan biography. Don't know that I'm a fan of the Mongol revisionist trend, however, although I suppose worse things have come out of academia. :P