Dear Friends,

I’m very happy to have a piece out on spirituality and the American presidency in Arc Magazine. Arc, re-launched by

of the writing Oppenheimers family, is a magazine to pay attention to. It takes on the wide nexus of religion and politics and features a number of Substack familiar faces. The piece — which involved a lot of research — starts with Marianne Williamson and works backwards from there to Abraham Lincoln’s séances, Henry Wallace’s Theosophy, Warren Harding and Ronald Reagan’s astrology, Donald Trump’s Pealeianism, etc.Best,

Sam

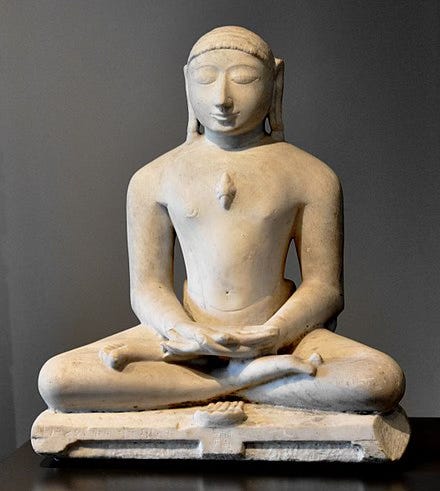

WHY I AM A JAIN

This one is easy. I am taking my tour of world religions — treating each as an accumulation of social wisdom and finding value in each — but, with no disrespect intended to any of the others, Jainism is the only one that actually makes sense.

Jainism is based on a simple, inalienable, and apparently irrefutable principle — that a good life is one in which one does no harm. All living things are deserving of life, contain with them infinite worlds, and at a profound level are equal in worth to all other living things, and therefore causing harm to another living thing — let alone killing — is an act of infinite cruelty and beyond understanding or forgiving.

From Jainism, it follows almost immediately that one would be a strict vegetarian and would try to live one’s life in accordance with ahimsa — the attempt to do no harm. Strict Jains, with commendable consistency, also cover their faces to avoid inadvertently swallowing insects and lightly brush their path in front of them to avoid stepping on ants or (as much as possible) microbes.

I can find no real argument with Jainism. A similar sensibility — although not codified in any tradition — informs some of my own actions, my nearly lifelong vegetarianism and some critical decisions I’ve made. From that point of view, anything that you might desire — let’s say, the iron and muscle mass that comes from eating meat — has to be weighed against the harm that it causes, and as much as, at different points in my life, I might have wanted to bulk up or to fit in, etc, that almost always struck me as outweighed by the obvious harm of contributing to the deaths of however many thousands of animals solely for my own marginal benefit. That sort of calculation shows up in more subtle ways as well. In a culture that emphasizes fulfillment as some absolute good, Jainism offers a valuable and searing corrective. At some critical level, your ‘fulfillment’ matters no more than the life of the ant that you stepped on during your morning run or the fly you swatted away as you were focused on your deliverable — and that sense of underlying humility has to stay with you if you have any hope of living an ethical life.

But in Jainism, at the same time, there is a deep sense of tragedy. We are predators, we are part of a cycle of existence that is cruel, and we cannot exist in the world, let alone flourish, without doing harm. Our lives then are inscribed in compromise and in the sense of the tragic.

In my life I have never, I don’t think, met a Jain. I was in a Jain temple once in India — it was covered in mirrors, which I found very interesting and impressive. I took a course once on Jainism, in which the teacher was careful to emphasize that, in Jainism, like in all religions, a great deal of ingenuity over the millennia has gone into finding the loopholes, seeing how the strict non-negotiable tenets of Jainism can be made compatible with the facts of our human existence, with our inability to, for stance, draw a breath or take a step without, on the microbial level, causing a holocaust of harm.

I had an acute sense of what the psychic costs might be from strict Jainism through a breathtaking chapter in William Dalrymple’s Nine Lives. Dalrymple meets a Jain nun, Prasannamati Matiji and she tells him the story of her life and of her mourning for her fellow nun and traveling companion, Prayogamati. Mataji was born to a lay Jain family, she had a happy childhood, but she chose — entirely freely — the path of diksha, of the monastic life. It was an arduous process. At 14, she underwent a ceremony in which, one by one, she plucked out all the hairs of her head. She tied a ribbon around the arm of her two brothers and a ribbon around the arm of her father and cut the ribbons to signify that, from now on, they were perfect stangers to her, just like everyone else. Her parents, though believing Jains, deeply disapproved of the decision she had made. On a visit from her sangha (nunnery), her parents tried to keep her at home, and Mataji put herself through a three-day hunger strike until hthey relented.

The Jain custom is for nuns to always travel in pairs, and this — for Mataji — was her downfall. She was assigned to a nun named Prayogamati and, for fifteen years, they were together for every moment of every day. They were hungry together and tired together, they shared exactly the same sense of humor. Their periods were perfectly synchronized. The Jain rule was never to spend two nights in a row under the same tree. They walked all day, fanning the ground in front of them, and, when they were hungry, put their arms over their shoulders — as a signal to strangers to give them scraps of food.

After fifteen years exactly like this, Prayogmati walked a little ahead of Mataji in a poor village in Maharashtra. She got a parasite from a dirty stream and from that parasite contracted dysentery. Prayogamati probably could have healed, but she chose instead to take sallekhana — to fast to death by every day slightly reducing her intake of food and water.

Mataji was with her when she died, and when she slipped away, Mataji wept bitterly — earning a rebuke from her guruji. In the morning, she went back out on the road, and — as she told Dalrymple — “It was the first time as a nun that I had ever walked anywhere alone.”

At the time Mataji met Dalrymple, she was about to undergo her own sallekhana. She was only 38 and in good health, but she had concluded that it was time. She did so, however, with an uneasy conscience. Prayogamati had undergone her sallekhana in apparently perfect confidence, but Mataji couldn’t manage it. She prayed every night to be released from her attachment to Prayogamati and it never worked. Everything in her training, everything in her severe renunciations, had been with the intention of avoiding attachment of all kinds, but when it came to Prayogamati she couldn’t be free of the memory of her — and couldn’t forgive herself for her weakness.

My first reaction, reading this, was immense pity for Mataji. The feeling was that she just hadn’t had the opportunity to express, to fulfill herself. She loved Prayogamati. In another circumstance, they might have been very happy and lived a very long life together — if only their severe asceticism hadn’t gotten in the way.

Now, I am far less sure. I do find there to be something admirable about the choices that Mataji and Prayogamati made — their non-greedinesss and non-selfishness, their sense that life could be very simple, just a walking-through the world and experiencing no despair when it is time to leave it.

The challenge to my Jainist disposition came from reading Osho and some of the literature of Tantra. For Osho, the path of the yogi — which was the path of somebody like Mataji — was all perfectly-well-and-good but it was very narrow, a deliberate reduction of the world, and therefore a limited way to reach enlightenment. There must, Osho and the Tantrists reasoned, be some other way to obtain enlightenment — something that took in more of the complexity of the world, something that was more in keeping with the capacious and predatory nature of human beings. Osho, like his Tantric forbearers, encouraged paradoxes, sexual abandon, the eating of meat, the embrace of cruelty — of living life to its absolute fullest. Towards the end of his life, he was heard on a wiretap remonstrating with himself that he had never actually killed anybody.

And that self-remonstration, that shortcoming of Osho’s according to Tantric principles, did, it seem, expose the hollowness of the whole Tantric project. What was so great about self-fulfillment or self-knowledge or even enlightenment after all? — especially if it came at the cost of anyone else.

I went through my Osho phase feeling, in the end, closer to Mataji. Of course it is not possible to make oneself as small or as perfectly-harmless as strict Jains would advocate — sallekhana is certainly not a path for anyone except fanatics. But it did seem like a useful antidote to the gospels of self-fulfillment that are so baked into Western culture. A person could be themselves, could honor their own vibration — it seemed like an insult to the design to do anything less — but it was equally important for a person to develop a deep humility, to understand that no matter what they did they were never more important than anyone else, or for that matter, never more important than any other life form. It was a hard lesson but it struck me as something that the culture needed to learn.

I presume that a prohibition on harm also applies to risks of harm. But every action risks harm. Even inaction risks harm. And so it seems that their idea of a good life is one that never comes into being.

This is fascinating, thank you. I’m very interested in mystical Christian theology, but also enjoy learning about other faiths. Sometimes I feel like theology can get in my way. The simpler I can keep things, the better, but I’m always drawn to reading and learning more. Like most spiritual things for me, it’s a paradox.