I’m going to do a series of posts on the election. Sorry for this! After, we can get back to talking about, like, life — but I do want to try to really process the lessons of the elections before all this gets memory-holed.

The first piece is the easiest. This election is the straw that broke the back of polling. After every election result that goes wrong, the pollsters have always had an excuse. 2016 was an anomalous election. In 2020, the polls were off but the polls got the right man in the end. Here, though, there really is no alibi. The polls all said, with absolute consistency, that the election was too close to call — and, in the end, it wasn’t. Trump walked away with it in all the swing states.

What this tells us is that it’s not a problem of methodology or anything like that. The problem is with polls themselves. My suggestion would be for anybody in politics to throw away their polls from this day forward. There simply is no substitute for EQ, for reading the room — and the room, all through the fall, was telling us that Trump had tapped into the collective psyche (the assassination attempt, the McDonald’s photo op, the podcast appearances) and Harris just hadn’t. For the most part, polls are harmless — what else is there for us to do before Election Day? — but for people making decisions about election strategy, reliance on a fundamentally-flawed metric is worse than useless. In the Democrats’ case, it led to a false sense of security all the way through the election cycle, right up until Election Day. I suspect that, more than anything, it was inflated poll results that resulted in Harris’ tepid campaign when she should have been running as an underdog the entire time.

The case against polling was closed for me through this article in MSNBC. This is David Byler trying to defend the pollsters’ performance:

Despite what you may have been hearing, the polls did well. No, the data wasn’t perfect, and the industry still faces long-term challenges. But we’ve proven that we can get close to the mark — which is the best we can reasonably expect from polling.

In the states that decided the election, the polls were generally off by 1 to 3 points. In the national popular vote, the RCP average had Trump ahead by 0.1 and he’ll likely win by 1 or 2 points. For polls — blunt instruments that typically use less than a thousand interviews to estimate how an entire state or nation feels — a 1- to 3-percentage-point error is great.

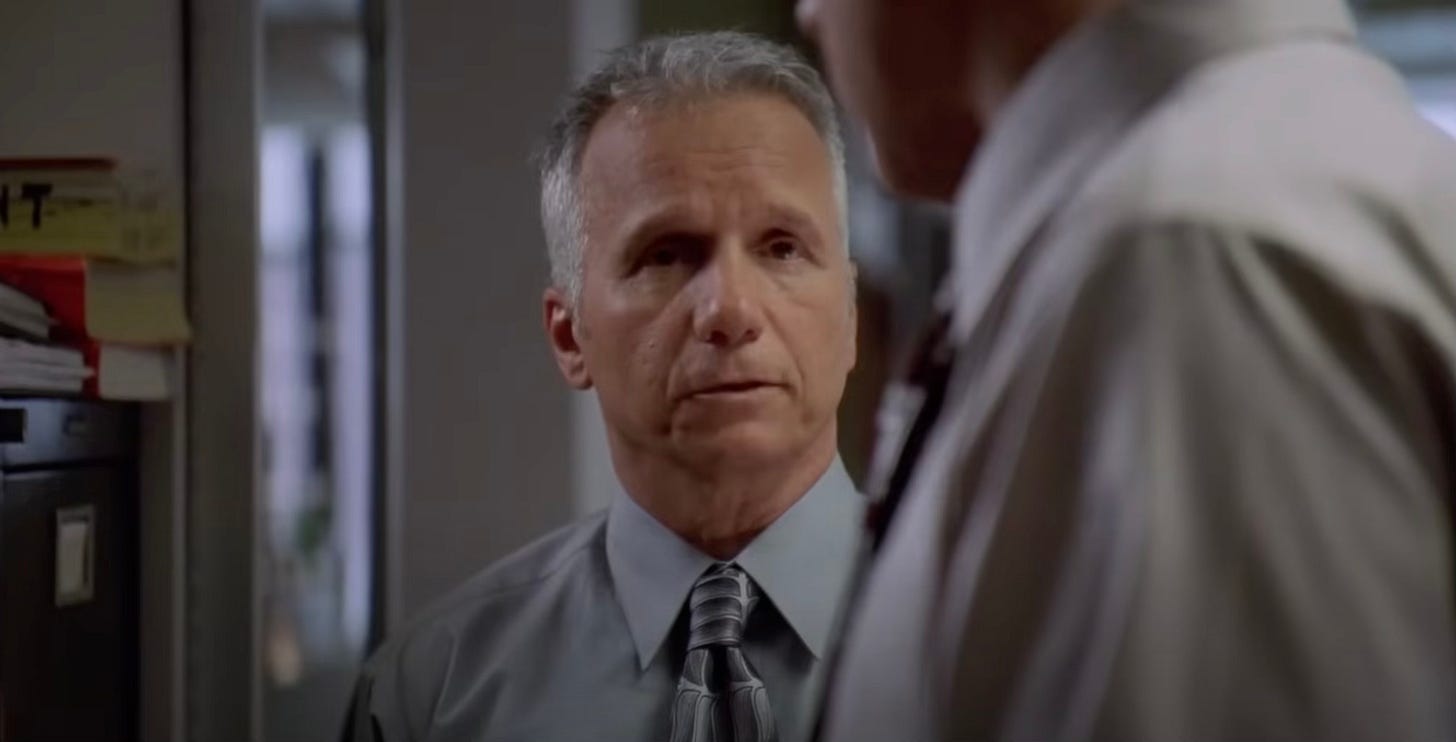

Right. So as Major Rawls puts it to Santangelo in The Wire: “Shit, when it comes to dunkers you solve maybe six, seven out of ten, but a stone fucking whodunnit —” If polls only tell us who’s going to win in a blowout, then they’re not really that useful, are they? If polls tell us nothing in a tight race — because the differential in the race is within their margin of error — then it’s hard to see why we bother with the exercise.

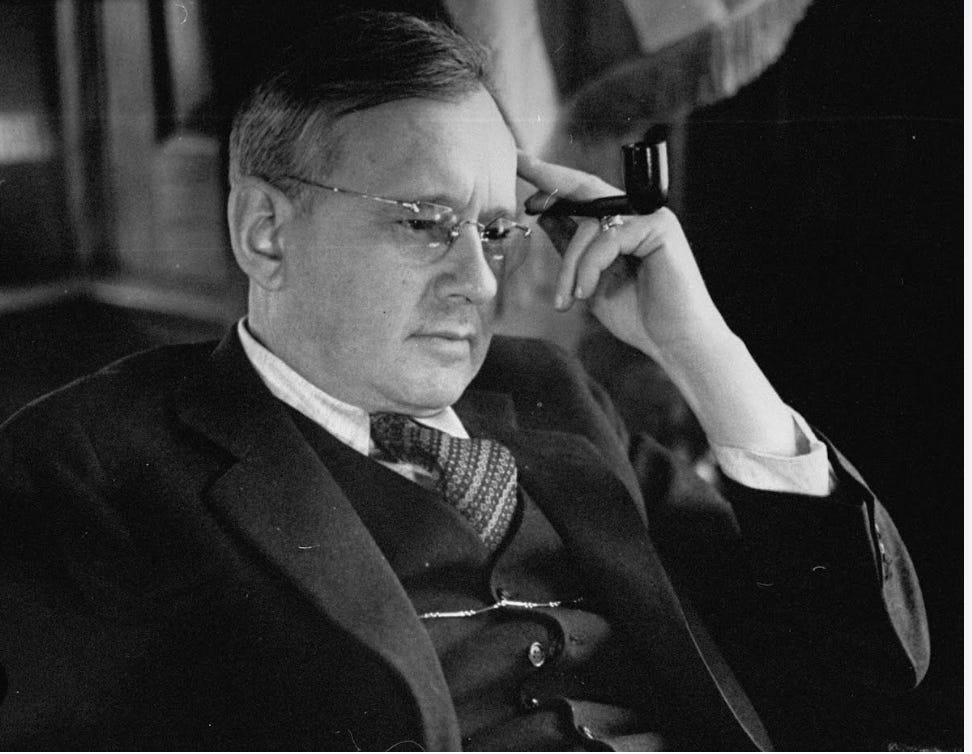

It’s worth recognizing that modern polling developed in the 1930s but not initially for political purposes. Polls were market research for advertising companies. It stood to reason that these kinds of surveys could be extended to politics, but, from the beginning, the results were less-than-impressive. In 1936, the widely-respected Literary Digest survey predicted a sweep for Alf Landon — not thinking that Literary Digest readers were disproportionately Republican. In 1948, the pollsters closed up weeks before the election out of completely confidence in a Thomas Dewey victory. In 1976, the last Gallup poll before the election incorrectly predicted a win for Gerald Ford. In 1980, the polls showed Jimmy Carter leading all the way into October — and with no one predicting Reagan’s sweep. In 2000, the polls predicted a clear win for George W. Bush — a significant difference from the Election Night nail biter. In 2012, the polls significantly underestimated Obama’s advantage. And then we get into the Trump era.

The sense is that polls hit their high-water mark in the 1990s/2000s. The introduction of advanced demographics allowed Bill Clinton and Mark Penn to build Clinton’s 1996 campaign (and to deeply shape Clinton’s policy agenda) with carefully tailored data. The polls were more right than not in the elections of this era. But those elections were about as close as the real world could get to lab conditions — with two super-solid parties speaking essentially the same language as each other and competing for a narrow band of swing voters in the middle. The argument for polling would be that if the Trump madness passes, then the parties return to something like a normal balance — but there really is no reason to believe that that would be the case. The two perfectly-balanced parties may be more the anomaly than the norm, and, for a long time to come, we will have to rely on our intuition and our acuity rather than some quasi-science to understand what’s going on.

Byler says something else that really should disqualify polls altogether. He argues that pollsters do the best they can given that 99% of survey recipients ignore the surveys.1 But if 99% of those surveyed ignore the polls, then the polls simply lose all their value. A large number of those surveyed are still going to vote; they’re just like any normal person who would prefer to not have their time wasted by a survey. By citing the relatively small number of people who answer pollsters, polls are fatally skewed towards high-information-type voters who, like Landon’s magazine-reading constituents, would be inclined to vote for the establishment candidate. But the real purpose of a poll is to try to access the mind of low-information voters who — since they don’t answer polls — are unreachable in polling methodology.2

All of this should be obvious enough when we think about the inherent limitations of polling, but for some reason we keep getting our fingers burned in election after election. It’s finally time to learn from our mistakes. There’s no quantitative substitute for common sense.

99% may be high, but by all accounts the percentage of responding recipients has dropped steeply since the landline era.

Thank. You.

“polls are fatally skewed towards high-information-type voters who, like Landon’s magazine-reading constituents, would be inclined to vote for the establishment candidate…”

This was the essence of my day-after-election text message rant to a friend. Pollsters don’t seem to have caught up to the reality that we aren’t all feeding from the same information pools anymore. And the people who are motivated to participate in polls (to your point above) tend to be very civic minded anyways. The folks who aren’t? They’re not taking the fucking polls … as we can clearly see now.

I’m so glad it’s not just me who’s pissed about the polling ...

Great reminder of the inherent limitations of polling, especially of the problem and effects of extremely low participation in the polls--super useful.

One question: doesn't this argument suggest limited usefulness, rather than none whatsoever? You are saying "If polls tell us nothing in a tight race — because the differential in the race is within their margin of error — then it’s hard to see why we bother with the exercise." -- but I guess you would not know the race is within the polls' margin of error without some sort of a poll?

I think our frustration has been not only with polling itself (pollsters are pretty clear about their margin of error, and they really weren't that far off, which is pretty amazing given the situation you are describing so well)--than with the idiotic, obsessive overuse of polls in the media we consume? Results are within margin of error: ok, just say that, and please don't put the numbers on the front page.

Media hysteria based on the weather forecast is not a bad analogy?