TOMMY ORANGE’s There There (2018)

Who are we kidding here? There There won every prize in sight on its publication in 2018, got 5,000 five-star reviews on Amazon, and nothing but glowing reviews from the mainstream press. “Yes, Tommy Orange’s New Novel Is Really That Good” was the headline for Colm Toibin’s New York Times review.

So the question is if 6,000 Amazon readers – and Colm Tóibín – can be so badly wrong, and the answer is, yes, of course. Tucked into the Amazon reviews is the lonely opposition of the one-star crowd – “I am quite shocked by the profound amount of positive reviews from highly revered critics”; “Worst book I have read in this lifetime!”; “I was so irritated that I didn’t even donate the book after reading, It went straight into the recycle bin” – and there’s a certain sense of shocked disbelief, which I share, that the entire critical apparatus can allow itself to be so outrageously fooled. Because – as the Amazon opposition party notes – there’s no universe where There There is good writing. Most of it is remedial – “It was raining. The kid was in the back.” – but sometimes it lurches into the territory of jaw-dropping awfulness. “I’m on the toilet. But nothing is happening,” could well be the worst opening to a story I’ve ever read. Well, unless the worst line is this, from a few pages later: “And I can neither shit nor not shit.” And it truly is strange that none of the five-star reviews, and not Toibin, who may have been laughing all the way to the bank, seem to notice any of this.

The explanation is political, of course. There There appeared at a woke peak in 2018, before any kind of aesthetic pushback could organize itself. The assumption was that the direction literature would take had to come from marginalized voices, had to be angry, and had to break some kind of barrier of good taste – had to speak from the true heart of the society. And There There checked all the boxes. I was really stunned to look at the back cover and see the accolades from critics who normally would be tougher on “And I can neither shit nor not shit.” Dwight Garner writes, “There There’s appearance marks the passing of a generational torch. And Louise Erdrich: “Welcome to a brilliant and generous artist who has already enlarged the landscape of American fiction.” And Marlon James: “There There drops on us like a thunderclap; the big, booming, explosive sound of twenty-first-century literature finally announcing itself.”

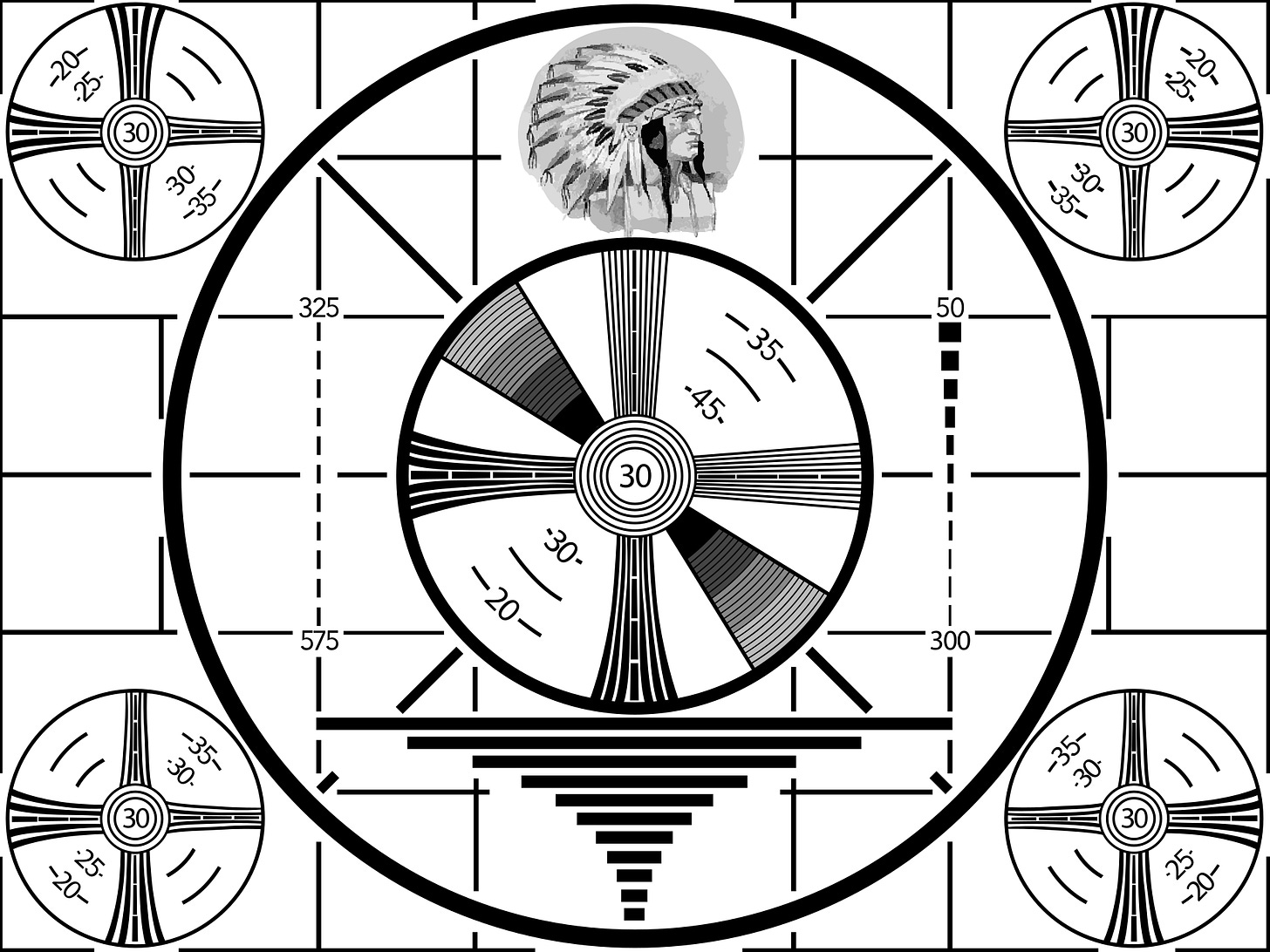

Not only was There There unassailable in terms of content – Native American characters written by a Native American, stories from the mean streets of Oakland, a grappling with the logic of mass shooters, a final scene at a powwow – but Orange had preempted any possible criticism with a blistering prologue laying out the entire history of genocide against Native Americans from the treachery of the Thanksgiving meal to the Indian’s Head test pattern on broadcast TV to the “stray bullets and consequences that are landing on our unsuspecting bodies even now.” White America was so illegitimate – as white America has always half-suspected itself to be – that there was no possible critical response except to wave forward a text as righteous and furious as There There.

The dynamics of the coronation of There There. and of the neither shitting nor not shitting narrator, as the long-awaited “thunderclap of twenty-first-century literature” are so familiar at this point that they’re almost not worth discussing. Just a couple of small points to make about this variety of woke literature. Key to it is the rhetorical device of moving seamlessly between brutally violent and not-so-obviously violent events and treating them as irreducibly part of the same phenomenon. Somehow these three events making up the prologue – 1.Massacres carried out against the Wampanoags in the 1620s, “Metacomet was beheaded and dismembered. Quartered. They tied his four sections to nearby tries for the birds to pluck”; 2.The Indian’s Head test pattern on TV, “The Indian’s head was just above the bull’s-eye, like all you’d need to do was nod up in agreement to set the sights on the target”; 3.The urbanization of Native Americans, “The bullets moved on after moving through us, became the promise of what was to come, the speed and the killing, the hard, fast lines of borders and buildings” – strike me as being very different from each other, different in kind and in the scale of brutality. But not so, according to Orange. The impulse that constructs modern cities, that selects the Indian Head as the image to accompany tone-setting on broadcast television, and that decapitates and dismembers Metacomet is understood to be the exact same impulse – bent ultimately on destruction and exploitation no matter how benign its manifestation might seem to be at any given moment. In that conflationary mindset, the Indian Head test sign is an invitation to a shooter training a rifle; a robbery gone wrong at a powwow is a racist massacre against Native Americans – and, in the narrative structure of There There, one leads inexorably to the other. I’ve come across that device as well in, for instance, Lidia Yuknavitch’s Verge, which opens with organ-running in Ukraine and, without skipping a beat, shifts to micro-aggressions in Oregon, to the horrors of, for instance, a perfectly cordial neighbor wearing a MAGA hat as a way of insisting – although it barely even needs to be stated – that the underground kidney trade and the sartorial choice of the neighbor are part of the same malignant phenomenon and that, given the formidable challenges of saving the world, change might as well start right here at home, by saying something nasty to the neighbor.

This line of thought leads not only to some stunning leaps in logic and the assignment of culpability but to heroically awful writing. Orange isn’t quite as unhinged as Yuknavitch in this art of radical conflation, but he’s up there. A character in Orange Orange, discussing the perennial problem of women being kidnapped at highway crossings and then beheaded, explains, “The difference between the men doing it and your average violent drunk is not as big as you think.” Or, as a fresh nomination for the worst-sentence-ever-written, a maintenance man in a philosophical mood reflects, “This world is a mean curveball thrown by an overly-excited, steroid-fueled kid pitcher, who no more cares about the integrity of the game than he does about the Costa Ricans who painstakingly stitch the balls together by hand,” So! What are we most upset about here? In multiple choice format – a) that we are born unwillingly into this vale of tears; b) that Major League Baseball is in unholy economic alliance with sweatshops in the developing world and that its fanbase is different to the phenomenon; c) that, in the steroid era, all records are untrustworthy and the Hall of Fame itself is an unreliable arbiter of quality? The answer, of course, is d). We are equally outraged about each one of these interconnected issues.

This mindset may help to explain a device that I’ve found puzzling in other woke works – it’s here, in Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, in Miranda Popkey’s Topics of Conversation. In all of them, the narration keeps pausing, as if for a word from sponsors, to run past a whole potpourri of unrelated factoids. In There There, we are treated to information about the Oakland Athletics, the gastrointestinal system, Gertrude Stein, 3D printing, the chemical composition of blood. I’m not ungrateful for these asides – I learned things! – but they really have nothing to do with the point of the story that’s apparently being told and, if they do anything, they serve to collapse the narrative into a far-ranging malediction. These are just a few of the very many things that are wrong in the world, the narration seems to be saying, and were there world enough and time we would cover all of them. This strikes me as closely related to a phenomenon that appears here and in Yuknavitch, in which the narrator falls into sputtering silence and tries to negate what he or she just said. Of the ‘I’m on the toilet but nothing is coming out’ scene, Orange himself seems to be startled at how bad his writing is and comments, “This feels true about my life in ways I can’t articulate yet. Or like the name of a short-story collection I’ll write one day, when it all finally does come out.” To parse that for a moment, what Orange is saying that he knows that the book he’s given you is a misfire, a first draft, but that when he really gets the creative runs – and ‘I’m on the toilet. But nothing is coming out’ is the name of an entire short story collection and not the mere opening line of a single story – then what he writes will be extraordinary, and in the meantime it at least has moral urgency and is informative about the manifold miseries of the world.

To try to not be snide and to see things from Orange’s perspective, it’s possible to say the following for There There. It’s not as if he’s wrong that the beheading of Metacomet, the Indian Head test pattern, and the construction of American cities are interconnected – the cities are all built on land that belonged to Indians, it is absolutely true that present-day Americans who “follow the sleeping tiger of their last name” may well find that “their ancestors benefited directly from slavery and/or genocide,” and if the prose linking the steel beams of skyscrapers to the bullets ripping through Native Americans is sort of unsubtle and graceless, well, there’s nothing very subtle about four centuries of genocide and expropriation. And the sacred anger that Orange summons – and that was so admired by so many thousands of Amazon members – does create a narrative that’s rippling with permutations of violence. He’s not bad on the mass shooter phenomenon – a difficult thing to write about – and, within the narrative, the 3D printing of plastic guns and the sneaking them into a crowded event, feels kind of normal, a natural extension of the nihilism that seems to permeate everything in America. And, in its outline form, the structure is terrific – all the characters converging on the powwow, the powwow spelling doom for many of them, and the bulk of the novel being comprised of the inner monologues of all the various characters. Those elements all make for a great novel, but, unfortunately, that’s not this novel, which just keeps digressing, keeps falling into incoherence, keeps missing its targets. So what to do with a text like Orange Orange? Well, just what everybody seemed capable of doing before 2015 – of separating the moral worthiness of a work or art from its quality. Of course there’s room for great literature about present-day urban Indians, about the legacy of genocide, about the nexus of historical trauma and present-day poverty. But in literature it’s not enough to be right – you have to be good as well. And There There comes across like a practical joke that took in the whole publishing world.

JARON LANIER’s You Are Not A Gadget (2011)

Jaron Lanier has a star turn on the documentary The Social Dilemma. “So, do it! Yeah, delete. Get off the stupid stuff. The world’s beautiful. Look. Look, it’s great out there,” he says, which doesn’t exactly sound so brilliant or novel – whose grandparent hasn’t made exactly that point? – but it really hits a nerve where it’s placed at the end of The Social Dilemma and I think I can date my own fast-developing Ludditism to exactly that moment, sort of in the way that people sometimes will watch a documentary and suddenly give up eating fish or meat.

So ever since then Lanier’s You Are Not A Gadget, his 2011 anti-manifesto, has had an outsize place in my imagination. I’ve thought of it in the same category as Martin Gurri’s 2014 The Revolt of the Public – one of the key texts through which people started to figure out, like in a twist in a suspense movie, that something had gone terribly wrong in the ineluctable rise of the internet, that our favorite new toy, instead of expanding consciousness and connectivity, was actually sapping us of any control over our own lives. I was really late to all of this. I remember coming across a headline of a New York Review of Books article called ‘We Are Hopelessly Hooked’ and – this is as late as 2016 – sort of squinting at it in disbelief, assuming that that was a case of old fogeyism but also sensing that there was a perspective here that I hadn’t really considered, that maybe the internet wasn’t synonymous with progress, that maybe the internet was just awful. And – with the usual over-literalism of somebody going into recovery – I came to attach great significance to people like Lanier who had been attuned to the issue and laid out some path to wellness back when I was hopelessly hooked and not even aware of it.

And now, finally getting around to reading it, You Are Not A Gadget is both more and less than what I thought it was. It’s not The Revolt of the Public – a tour de force of intellectual analysis that lays out a comprehensible framework (a theory of the transmission of information) through which it’s possible, with startling ease and accuracy, to understand virtually all of the seismic rifts that have torn apart civil society over the past decade. Much of You Are Not A Gadget is dedicated to long-running internecine squabbles that Lanier has been having within the tech community since the 1980s. For the most part, it reads like the work of some Trotskyist defector explaining that, while his own motives were always pure and Marxist-Leninism remains a beautiful system, the revolution has been hopelessly hijacked and corrupted – and, coming from the place of tech illiteracy that I am, it’s difficult to evaluate whether Lanier is being precise or vendetta-ish in identifying various events in tech history, UNIX, MIDI, the adoption of the ‘open culture’ gospel, the web 2.0, as being the worms in the apple, the moments when utopia curdled. But you can’t have a techie manifesto (or anti-manifesto) without its biting-off-more-than-it-could-possibly-chew, and Lanier’s digressions into philosophy, aesthetic theory, and business history are more interesting than most and serve, in the domain of ideas, as a strikingly useful antidote to decades-worth of pusher-talk by the futurists and open-web proselytizers – Narcan to the lethal ideologies that Silicon Valley has been cheerily cooking up.

The Communism analogy actually isn’t completely random. What Lanier complains about most is what he calls ‘digital Maoism.’ That would seem an odd term since it’s elsewhere described as a “blend of cyber-cloud faith and neo-Milton Friedman economics,” but it’s chosen advisedly – and refers to a certain cybernetic totalization that somehow got locked into Silicon Valley as an article of faith with its Little Red Book-y snippets of wisdom, ‘information wants to be free,’ “we’re all broadcasters now,” “the singularity is near,’ etc. “This ideology promotes radical freedom on the surface of the web, but that freedom, ironically, is more for machines than for people,” writes Lanier. The half-thought-through principle of ‘openness’ becomes an absolute, together with the never-questioned belief in the essential goodness of the machines and the machines’ link with ineluctable progress, and the tech crowd blithely allies itself with entities – platforms, etc – that seem to promote ‘openness’ but in fact create grossly hierarchical power structures online as well as a vast graft system of kickbacks and pay-to-play schemes through advertising and data mining. You Are Not A Gadget was written before the ravages of social media were fully apparent – and the central thesis of The Social Dilemma, which is that the ostensibly free internet has created a new economic model in which the ostensible consumer is actually the product and whose consciousness is being parceled out and sold to a dizzying array of entities, is nowhere to be found in the book – but Lanier has his finger on the pulse and knows exactly where ‘the open web’ is going: corruption and pyramidization wrapped up in high-minded cant, a neatly Animal Farm-ish inversion of everything that the web pioneers stood for. “This digital revolutionary still believes in most of the lovely deep ideals that energized our work so many years ago,” Lanier writes of himself. “At the core was a sweet faith in human nature. The way the internet has gone sour since then is truly perverse. The central faith of the web’s early design has been superseded by a different faith in the centrality of imaginary entities epitomized by the idea that the internet as a whole is coming alive and turning into a superhuman creature.”

And the emotional core of You Are Not A Gadget is exactly that trajectory of the old revolutionary, remembering the golden days when he sat around playing Indonesian wind instruments with the other digital revolutionaries, railing against what was at the time the narrow horizons of the tech powers-that-be, dreaming of the bright futures of the world wide web and of virtual reality. For Lanier, it takes – as Lana Del Rey would put it – “getting everything you ever wanted and then losing it to know what true freedom is.” And, for Lanier, seeing his wildest dreams come more than true and then distorting in just as fast a period of time, gives him a unique perspective on what went wrong: basically, a few of his buddies got carried away with a pernicious and self-serving ideology and everybody else took them too seriously. “What’s gone so stale with Internet culture that a batch of tired rhetoric from my old circle of friends has become sacrosanct?” Lanier wonders at one point.

And, in some sense, the answer is as simple as what the humanities people were accusing the techies of all the way through the second half of the 20th century (before the techies stole the means of cultural production, that is) – that the tech crowd just didn’t get how culture actually works. Silicon Valley, in a breathtakingly direct call-back to Maoist and Stalinist rhetoric, claimed that there would be a period of transition in which art would be disrupted, in which new mediums of exchange would have to be adapted to, and then the principle of openness would kick in and art and culture would be generated beyond the wildest dreams of anything in the old IRL dispensation. That Lanier was less prone to drinking that particular batch of Kool-Aid may well have been that he’s an artist himself and knows the resonances with tradition, the turbulences of the soul, that drive actual art. “A common rationalization in the fledgling world of digital culture was that we were entering a transitional lull before a creative storm,” writes Lanier of the early days of the world wide web. “The sad truth is that we were not passing through a lull before the storm. We had instead entered a persistent somnolence and I have come to believe that we will only escape it when we kill the hive.” And, to a surprising extent, that flattening of expression, that diminishing of art is, for Lanier – more so even than the damage done to the collective attention span or to IRL economies – the real indictment of the web revolution. “Pop culture has entered into a nostalgic malaise,” he writes. “Online culture is dominated by trivial mashups of the culture that existed before the onset of mashups. It is the culture of reaction without action.” The real problem is deracination itself: exchange through the machine simply can’t replace exchange through living communities and as the machines get better the deracination only gets more acute. So the only solution – as Lanier understands by the 2010s – is to chuck the machine.

In his oddball way, Lanier has had about as good a career as any public intellectual in the 21st century. Various of his ideas – ‘digital Maoism,’ the need for a ‘creative middle class’ – have filtered out into the wider culture and became standard talking points for people who likely have never read Lanier. You Are Not A Gadget is a fairly simple and somewhat loosely-thought-through book, more of a broadside against tech orthodoxies than a fully-developed critique, but it put the tech world on notice that Silicon Valley gospel was no longer unassailable and it brought intramural tech debates into a wider public setting. Most of all, it played into a larger and very wide-ranging critique of where we’re headed, of which I’ve found the most cogent expression in Byung Chul-Han’s Psychopolitics: Neoliberalism and New Technologies of Power – the idea that ‘openness’ can be just as spiritually constrictive as more time-tested methods of repression; that ‘openness’ and ‘freedom’ are not goods in and of themselves, that they are tools that can be put to manipulative as well as productive uses, just as easily as the tools of ‘dominance’ or ‘control’; that even our most abstract political discussions tend to look in the wrong direction; and that the only standard for anything is the impossible-to-metricize, impossible-to-engineer flourishing of the human spirit.

Dora, the point being made here - @Castalia let me know if I'm speaking out of turn - is that a "middlebrow novel" like There There is representative of a whole style of literature, which incidentally is getting disproportionate attention and praise. We have become completely overrun by 'woke lit' and it's useful to try to analyze its components.

Why does nobody know about this Substack? This thing is so fucking good.