Dear Friends,

I’m sharing the second part of my series on Mormon history. The first part covered Joseph Smith’s prophecies and the growth of the Church in New York, Ohio, and Missouri. Sometime next week, I’ll finish up the series. At the partner site

, writes on Danielle Okri.Best,

Sam

MY MORMON OBSESSION

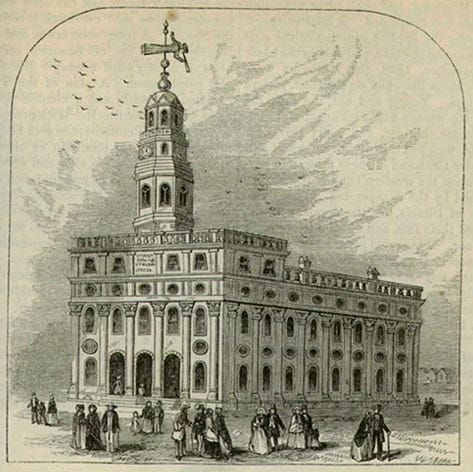

The fourth phase of Mormon history, in Nauvoo, is the one that most interests me. After the catastrophe in Far West and their expulsion from Missouri in 1838, the beleaguered Mormons settled at a spot on the Mississippi which Smith called Nauvoo — with his usual improvisational Hebrew, it was supposed to mean “beautiful plantation.”

There is nothing else in American history — or in world history — that is like Nauvoo. It is like a computer game expansion pack where Napoleon shows up on the Oregon Trail, or the Ayatollah Khomeini in the middle of Young Mr. Lincoln.

As everybody knows, the American spirit is supposed to be individualistic, democratic, with a jealous separation of church and state. The Mormons were communitarian, theocratic, and had absolutely no compunction about, say, voting entirely in blocs in state elections or placing all possible power in Nauvoo in the hands of Joseph Smith — and so much so that Smith, within a few years of his arrival in Nauvoo, was running for President of the United States and simultaneously establishing a theocratic kingdom that was meant to expand across the West.

The Mormons also proved to be astonishingly successful. They had suffered real persecution in Missouri. Upon arriving in Nauvoo, they were beset by illness. One of Joseph Smith’s most Napoleonic qualities was — no matter how far he advanced in career — to be accompanied always by his large and intensely-loyal family, but, in the first year in Nauvoo, just after he had escaped his Missouri jail, he endured the deaths of his father, his infant child, and one of his brothers. William Law, who would go on to be a pivotal figure in the Mormon story, recalled arriving in Nauvoo in 1841 and finding the Saints there to be “very poor but industrious.”

The Mormons, though, had a great deal going for them. Their ranks were filled with tough, dedicated, frontier people — in Nauvoo, as later in Utah, they would develop a reputation for dogged hard work. And the missionary activity that Smith had initiated from the inception of the Church was beginning to bear fruit — first with a wave of Eastern and especially Canadian converts; and then, most dramatically, with the English mission, where Brigham Young first proved himself, and which, given the poverty besieging industrializing England, produced by 1841 a deluge of immigrants to Nauvoo. And the arrival of a mass of fresh voters into Illinois was of interest to both political parties — with Smith making it abundantly clear that he would throw the Mormon bloc to whichever party most directly benefited the Saints. (In the 1840 election, for instance, the Mormons voted en masse for the Whig ticket, but, owing to a favor that a Democratic politician had given them, they crossed off at random the bottom name on the ballot, which just so happened to be a young state house representative named Abraham Lincoln.) And they had an ally in Springfield — John C. Bennett, the quartermaster general of the Illinois militia, who pushed through a highly-favorable city charter for Nauvoo and integrated the Nauvoo Legion into the state militia although, in practice, with absolute autonomy.

Smith now had complete control over his city and complete control over his fighting force — and had the privilege from the governor of giving himself the rank of Lieutenant General (the highest rank in the United States at that time), while, in turn, Bennett, a convert to the faith, became Assistant President of the Church, Mayor of Nauvoo, Chancellor of the University of Nauvoo, and Brigadier General of the Nauvoo Legion.

If the Mormons’ introduction to Illinois might have been written by Carl Sandburg, the arrival of Bennett in Nauvoo was straight out of Deadwood. Bennett was one of these classically improbable characters to show up on the Western frontier. He taught midwifery at an Ohio college and was a clandestine abortionist. His maybe most enduring legacy was that he helped to introduce the tomato into American diets at a time when it was widely believed to be poisonous. Much later on, when he had finished his Mormon phase, he would become an enthusiastic purveyor of chickens, so much so that an Iowa journal wrote a poem about it: “From Des Moines came Doctor Bennett / Champion of Shanghai chickens / Writing volumes about chickens / Chickens, chickens, chickens, chickens / Wrote of nothing else but chickens / Talked of nothing else but chickens.” In the 1840s, he was deeply connected with Illinois state politics. And he was, also, a scoundrel. As H.H. Bancroft would remark of the abundant affidavits of good character that Bennett later appended to his book, “When a man thrusts in your face three-score certificates of his good character by from one to a dozen persons, you may know that he is a very great rascal.” Through the horse-trading he carried out at Springfield, he rapidly ascended through the Mormon hierarchy to become Smiths’ right-hand-man.

Bennett was at the hub of a vast web of intrigue and criminality in Nauvoo — the full extent of which may never be fully known. The book Bennett wrote after he fell out with the Saints is so full of exaggerations — some of the features of Nauvoo named by Bennett, like the lurid ‘Chambered Series of Charity’ and ‘Cloistered Saints,’ may have been either a fragment of Bennett’s fantasies or else his own addition to the ‘plural wives’ doctrine — that it becomes very difficult to sort out fact from fiction. My favorite source on the hidden dark side of Nauvoo is a little-known account called “A Narrative of the Adventures and Experience of Joseph H. Jackson.” Jackson is the Mormon story as written by Cormac McCarthy crossed with Lord Byron. He writes very well, appears to have been very attractive and winning, really did “have the prophet’s confidence for a time,” as Brodie puts it and as the official History of the Church attests. But nobody knows where Jackson came from or what became of him after Nauvoo. He described himself at various time as a fugitive from Georgia, a Catholic priest, and a Western explorer who had lived in California. He claims in his book that he visited Nauvoo “from a romantic love of adventure” and arrived in the city already hired-out as an altruistic spy on behalf of the Illinois sheriffs closely eying Smith. As a Mormon bookseller whom I spoke with put it, “Jackson is reliable on everything except himself.” Jackson seems swiftly to have been inducted into the underbelly of Nauvoo. He pressed counterfeit currency in an operation overseen by Smith’s brother, Hyrum. He was encouraged by Smith to attempt to kill Lilburn Boggs, the governor of Missouri and the Mormons’ nemesis — one of several such attempts on Boggs. He participated in a posse attempting to kidnap an ex-Mormon giving testimony in a Missouri trial. “Nauvoo has been the hiding place of more stolen goods, horses, and thieves than any other place on earth,” he wrote. And he was privy to Smith’s athletic sex life — to the networks of women he visited outside of town and to the “Mothers of Israel,” older, respected women within the Mormon community, whom, Jackson claims, did much of the procurement for Smith.

Fawn Brodie — the preeminent historian whose framework I am following here — steers well clear of Jackson, but almost everything he wrote has corroboration somewhere or other. At the peak of my Mormon obsession, I got in touch with a handful of people, who referred to themselves as “the booksellers.” They seemed about the loneliest people you can imagine. They had all grown up in the faith but had come across the unsavory details of much of the Chuch’s early history and had apostatized. But they had only gone halfway. They were fascinated with this period — dug up copious material on it — but knowing that it was of no particular interest to anyone. Nauvoo occupied a peculiar blind spot in American history. Non-Mormons had next to no interest in any of this. And Mormons had thoroughly sanitized this history — Smith’s story had become hagiography, and the Nauvoo period glazed over en route to the far more majestic story of the westward emigration. The booksellers had also dug up material that went beyond anything in Jackson or Brodie. There was the story of Emma Smith, Joseph’s wife, attempting to poison him in 1843 out of fury over the spiritual wives. And there were several other poisonings and murders in Nauvoo that seemed to be traceable to the Smiths. This sort of naked gangsterism — and the disillusionment it had generated in sincere Mormons like the booksellers — brought me up short. The sense was that this wasn’t just fun and games, actually — that there was a wake of pain behind Joseph Smith’s endless self-creation. “He was a snake,” one of them said to me. “I like him when he was 12 years old and having visions. But after that…”

But at the time of my peak Mormon obsession, I wasn’t really in the mood for this pain and disillusionment. What I was interested in was the idea of the ‘kaleidoscopic personality’ — of something that seemed to be beyond the demarcations of good or evil, truth or lies, that there was an inner freedom that was both boundless and terrifying. Osho had it, Boris Vian has it in his fiction, El Greco’s portrait of Christ with the moneylenders has it — and, I was convinced, Joseph Smith had it.

In the early 1840s, he was at the peak of his power. He had successfully played off the Whigs and Democrats against each other. Anyone who could have revealed the dirty secrets of the Church’s founding had already left and done no real harm. He was universally beloved in Nauvoo and the converts — devoted to him and dependent on the Church — were pouring in.

Smith seems to have enjoyed everything about this time. And if I highly recommend listening to Nick Cave’s soundtrack to The Assassination of Jesse James when reading or thinking about the early part of Mormon history — it’s the right wistful tone, the sense of the country being built — it’s pretty much mandatory to listen to Cave’s “Jubilee Street” when thinking about Smith in Nauvoo. “Excitement has become almost the essence of my life,” he said in 1843. He was a living prophet, the spiritual leader of the Church, the political leader of the Mormon community, the resplendent commander of the Nauvoo Legion — and, in utmost secret, the King of the Kingdom of God. In the midst of that, he took ample time to wrestle, to play with children in the street, to entertain friends, and to continue with his adult education — studying Hebrew and the Bible (in Kirtland, he had hired out a rabbi to help him with his studies) and constantly tinkering with his theology. “He was a right jolly prophet,” one adherent said.

It’s nice to think about Smith in these terms — as reaching something like personal fulfillment and then sharing the gospel of how his followers could do it too. And much of Mormon theology has a distinctly hedonist streak to it. “Man is that he might have joy,” The Book of Mormon asserts. “He made of heaven a continuation of the good life on earth,” Brodie wrote. The aim would be to enjoy this world as much as possible — all the materiality of this world — and then to continue with pleasures very like it in the world to come.

And the most famous doctrine of Smith’s — the spiritual wives revelation — is to be understood very much in these terms. It seems clear that Smith had been playing around with polygamy as far back as Kirtland. By Nauvoo, he had around 50 wives and an almost machine-like system (as documented in part by Joseph Jackson) for keeping them all hidden from the rank-and-file Saints and, most importantly, from his wife Emma. But what separated Smith from a run-of-the-mill scoundrel like Bennett was that he had an idealism even with regards to his sex life and created a doctrine that turned his own polyamorous proclivities into a sacrament. This was a great deal of what he was up to when he was hidden away in his studies — reading the Old Testament and getting at the deeper meaning of the Patriarchs’ polygamy. The doctrine he finally unveiled, by fits and starts, and never completely openly, was that the ‘sealing’ would take place above all in the life to come — it was the responsibility for a man to look after his spiritual wives when in heaven, and the more responsible and impressive the man, the greater the number of spiritual wives. Many of the women Smith married were significantly older, and the sealing clearly was understood in a religious sense only. But, as so often with Smith, there was fine print — and the possibility of being sealed both “for time and eternity” i.e. in this world as well as in the world to come — set back into motion the machine-like system he had for visiting all his different girlfriends.

And coffee, you forgot to mention in what seems like a manipulation for the sake of not much except casting Yankees as demon-inflected/infected that the church forbade coffee drinking. The most occult bosses I have had have made it difficult for me to brew c at work. The Saints these Mormons are looking like they find no beauty in the independence of mind it takes to make art. If they went in for quick money at tge height of their tribal togetherness? No reasonable person would expect printing money to do except bring on a mexican standoff.