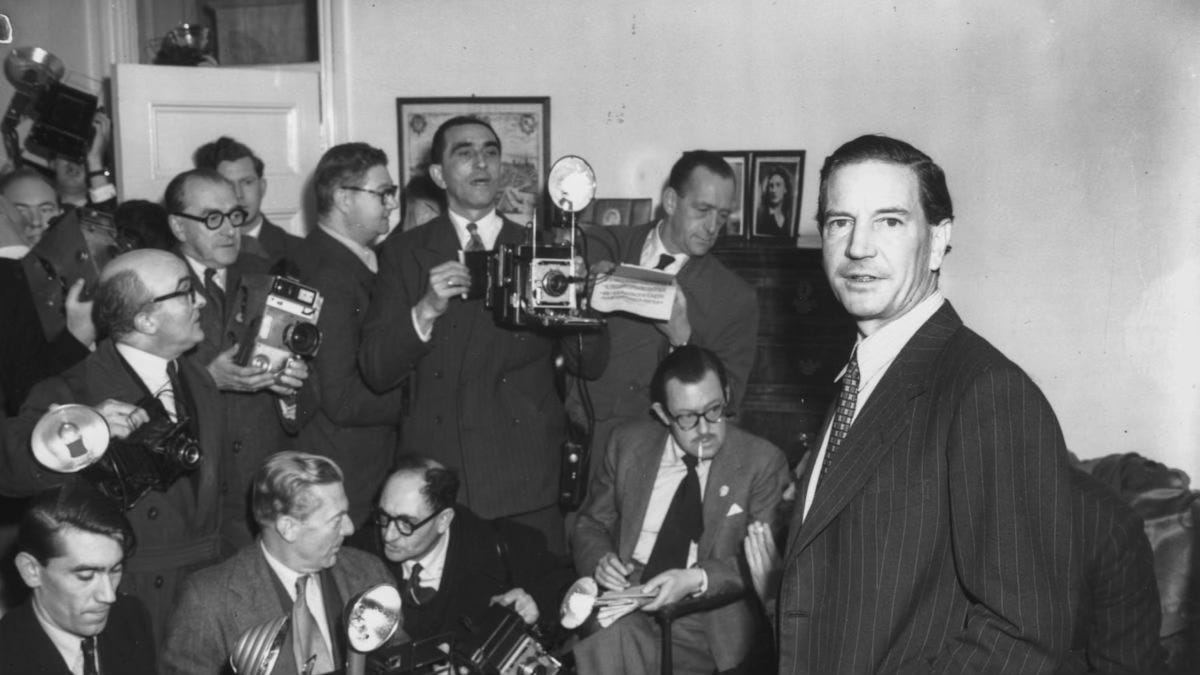

I was feeling a bit low recently, and that results in one very predictable outcome: doing a lot of reading about Cold War espionage. It wasn’t — thank god — trying to figure out the Kennedy assassination this time; but it was sort of the next best thing, which is the story of Kim Philby.

The excuse for getting into this is the Amazon series, A Spy Among Friends, about which I don’t really have much to say. It’s a serviceable adaptation of Ben Macintyre’s 2014 non-fiction work of the same title. The underlying idea is, instead of doing another reprise of the Philby story, to frame it through the friendship between Philby and Nicholas Elliott. That’s intelligent enough. Elliott was part of the same old boys network that produced Philby. They had a closely parallel career in MI6 and were very nearly best friends. Elliott became the service’s chief defender of Philby after his quasi-outing in the early 1950s. And then Elliott got himself dispatched to Beirut in 1963 to confront Philby with new, and damning, evidence and to extract a confession out of him.

This was a controversial assignment, and it has spawned copious conspiracy theories since then. Elliott did secure the confession, but he also appeared to leave the door wide open for Philby to run to the Soviet Union, which he promptly did. The conventional version of the story — as promulgated by Philby in his 1968 memoir — is that this was gross incompetence on the part of MI6. After securing a partial confession, Elliott — in the midst of uncovering the greatest betrayal in British intelligence history — suddenly had a pressing engagement in the Congo; and the man he deputized to take over Philby’s interrogation had an equally pressing ski holiday. Macintrye argues, plausibly enough, that it was better all around for MI6 to simply let Philby get away: a trial could only air out dirty laundry and lead to scandal. Elliott, in a 1986 interview with John le Carré (included as an afterward in Macintyre’s book), more or less confirmed that theory, saying, “No one wanted him in London.”

The Spy Among Friends series anchors itself on the Philby-Elliott confrontation in Beirut — shouting, atmospheric music, some montage-y sequences of men smoking on balconies — and then engages in a fanciful reconstruction of the scrutiny that Elliott might have been placed under on his return to London. He is interrogated by Lily Thomas, the no-nonsense, Northern-accented representative of MI5, the rival organization to MI6; he tips off Anthony Blunt, another member of the Cambridge Five, about Philby; he engages in a baroque spy-versus-spy game with James Angleton, the CIA’s counter-intelligence chief, who, back in the early 1950s, was taken in by Philby even more thoroughly than Elliott was.

None of this is exactly satisfying. Guy Pearce, as Philby, is the usual Hollywood shortcut — too handsome and too self-possessed (the real Philby, at the time of his confrontation with Elliott, was a falling-down drunk and nervous wreck). Thomas, it turns out, is a composite character, which, in a way, wrecks the entire premise of the show. We are so into the weeds of Philby and Elliott’s careers that to have the third leg of the triangle be a fictional character pulls into a completely different genre. In any case, Thomas’ character is a typical bit of woke-era unimaginativeness. Her African husband is a selfless doctor who is skeptical of her having anything at all to do with the old boy toffs who inhabit MI6. She uses the opportunity of the investigation to land some cutting criticism of the British class system — “my husband is a doctor, he works very hard and helps people, I have no idea what you all have been playing at for the last twenty years.” And, naturally, her feistiness and intrepidity earn her some begrudging inter-class admiration from Elliott. The only real takeaway from the Spy Among Friends series is the growing conviction that casting Damian Lewis is the secret sauce in any TV show you can think of. I could have sworn that I had just seen Lewis be a taciturn American Army officer before this; and before that he was a working man’s billionaire; and before that he was an American congressman with a dark secret; and now he’s a blue-blooded English spy — and is somehow, always, the most magnetic figure on screen.

What’s most interesting about Philby, of course — and which the series elides over — is coming up with a theory for why he did it. Macintyre, in the book, cautions against getting attached to any idea and settles, sagely, on the unknowability of Philby. That was the conclusion of Philby’s own handler, Yuri Modin, who, in 1994, wrote, “He never revealed his true self. Neither the British, nor the women he lived with, nor ourselves [the KGB] ever pierced the armor that clad him.” And anybody who speculates on what Philby was up to invariably runs into a Rorschach Test of their own prior beliefs. For some, it’s ideology — that Philby was a devoted and lifelong Communist (the position that he himself articulated most consistently in his later years). For others, it’s romance — and that’s what Philby is made to say in the show (he fell in love with Litzi Friedmann, a German Communist, in 1933, and stayed faithful to her spirit for the rest of his life). For others, it’s a gradual disillusionment with the West and the service (that’s the perspective of Philby’s stand-in in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy). For Macintyre, insofar as he proffers an hypothesis, it’s something closer to duplicity for its own sake, which aligns interestingly with the sensibility of English elite schools. “Philby’s story is that of a man in pursuit of ever more exclusive clubs,” Macintyre writes. “Westminster School and Cambridge University are elite clubs; MI6 is an even more exclusive fellowship; working secretly for the NKVD within MI6 placed Philby in a club of one, the most elite member of a secret inner ring.”

My own pet theory may not apply in this case, but I’d like to indulge it a little bit. That’s that spying, at some fairly early junction of the Cold War, evolved from “straight penetration” to something more like intelligence exchange. For many reasons, this was better all around. It was easier and safer. The hauls of intelligence were much greater. The governments of the spies’ home countries couldn’t fail but be impressed by what the agencies were bringing in. The agencies themselves came to develop stupendous power — since they were not only in, essentially, diplomatic liaison with their ostensible adversaries but were, in many cases, able to coordinate with them and to maintain a balance of powers. That approach aligned as well with the internationalist sensibility of the upper-crust — setting the British mandarins (and their American equivalents) apart from the more narrowly patriotic crowd that comprised the FBI or MI5.

If you read enough Cold War books, it’s possible to see this idea in the margins. It’s what spies seem to be referring to when they discuss a “higher loyalty.” It has clear roots in the intelligence-sharing that occurred with rings of double or triple agents towards the end of World War II (e.g. Dusko Popov, Reinhard Gehlen), with the spies themselves so thoroughly compromised in loyalty that their only conceivable value is as a conduit of information. It’s depicted with striking fidelity in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, in which the obsessive discussion of “moles” and penetration agents turns in a more interesting direction once it’s discovered that a high-level information exchange between the British and Soviet secret services has long been under way. “That’s how the game is played, you know that,” Toby Esterhase, one of its practitioners, says when cornered.

Elliott seems to allude to that idea in his interview with le Carré, saying that a Soviet spy caught and sentenced to 18 years in prison “wasn’t top league” — with the implication that the “top league” spies were exchanging far more intelligence and could do so with impunity. It’s stated very explicitly by Philip Corso, who must be taken with a grain of salt for different reasons, but who really was a Colonel in US Army Intelligence in this period:

The KGB and CIA weren’t really the adversaries everybody thought them to be. They spied on each other, but for all practical purposes, and also because each agency had thoroughly penetrated the other, they behaved just like the same organization. They were all professional spies in a single extended agency and trafficking in information….The CIA, KGB, British Secret Service, and a whole host of other foreign intelligence agencies were loyal themselves and to the profession first and to their respective governments last.

If that’s the case — and I do think that’s broadly true (or at least so logical that it would be surprising if it wasn’t true) — then a great deal falls into place. The old boy network isn’t just understood as classist snobbery — as the Spy Among Friends series is at such pains to make us believe — as a very necessary circle of trust for keeping the secret game from getting exposed by the roughnecks in the ordinary security services. That seems to be behind all the protestations of the value of “friendship” that people like Philby and Elliott are so anxious to emphasize — much to the bafflement of outsiders who couldn’t understand how Philby would have the audacity to speak of “friendship” long after it was known how thoroughly he had betrayed everyone in his life.

Philby comes to be understood as a critical cornerstone of this whole system — having been in contact with the Soviets back to 1934 and playing a complicated double game as early as the Spanish Civil War. Whenever this intelligence-sharing apparatus set itself up (and there was every reason for it to be established during the war), Philby was ideally placed to be a significant conduit of information if not policy. In that context, some of Philby’s more grotesque betrayals — for which he showed no apparent remorse — are more understandable. He betrayed efforts by the West to infiltrate resistance fighters into the Caucasus to fight the Soviet Union and into Albania to fight Hoxha. Those betrayals led to the executions of the agents, but imagining for a moment that Philby’s “higher loyalty” was to the balance of power, as opposed to just the Soviet Union, then those operations seem reckless and a threat to the international order and in need of discreet squashing. The whole Beirut episode makes sense in that line of thinking as well. The club that was involved in information sharing would have very much wanted to treat Philby with kid gloves — and would likely have preferred that he be handled by the broadly-sympathetic KGB as opposed to the rough crowd of MI5 — and made the accommodations for his departure. The long-running conspiracy theory (partly endorsed by the Spy Among Friends series) that Roger Hollis, then-head of MI5, was also a Soviet agent is more comprehensible if one just forgets about nationalities and views an intelligence agency is operating, at its core, in a sort of liminal international space of sharing and coordinating.

Macntyre’s version of these events is more drab and (it has to be admitted) fairly convincing. That’s the conventional story of friendships betrayed. Philby was off on his own (together with his ring), and people like Elliott and Hollis treated him with decorum because of class loyalties, their sheer inability to come to grips with the extent of his betrayal, and their desire to avoid scandal. And there is plenty of evidence to support Macntyre’s position. There is the very real consternation that Elliott displayed at the time of the Philby interrogation and then long afterwards — the moments when he lost his cool and shouted at him; the way he discussed Philby even long afterwards as a Soviet spy who had genuinely fooled him. “Betrayal takes courage. You have to hand it to Philby, he had courage,” Elliott said in 1986. And then there is the inarguable damage that the Philby escapade did to MI6. “Youth and innocence passed away and the dark ages began,” said Peter Wright of the news of Philby’s defection — the idea being that a genuine shock radiated through the system and that the shock was the very understandable reaction of being thoroughly taken in by someone trusted. Imagining that the ‘club’ was a step ahead the entire time — and largely feigning its shock at Philby’s betrayal — does venture into the realm of the conspiratorial and runs into some compelling evidence of how hard people at the time took it.

Like I said, with Philby everybody gets to a Rorschach of their own prior conceptions. I find myself reading and watching these things because I’m looking for hints of the intelligence-sharing theory. Somebody like Macintyre imposes a more low-key frame of friendships constructed and betrayed as the best way to understand Philby. And somewhere at the center of of all it, appropriately enough, is Philby, ever contradictory, ever inscrutable, either a one-off mole or an indication of a very different way of thinking about power.

I’ve always wondered at government horse-trading spies. Some event happens and suddenly twelve guys are kicked out of the country for being spies like it was discovered that afternoon. If everyone knew they were spies already what was the point? And then what is the value of kicking spies out if you know they’re spies and they don’t know you know. What better situation? And yet these fast exchanges of pawns happen a lot. Maybe it supports your thesis somehow.

The most interesting person in the whole Cold War spy setup was clearly Markus Wolf.

Wolf was German Jew, born the same year as Henry Kissinger. I really do think that Wolf and Kissinger lead parallel lives, that Wolf was a version of Kissinger who's family fled east instead of west. They each used intelligence and iron determination, but also a certain mystique attached to their status as Jewish refugees from Nazism, to wield massive and amoral power on behalf of the two blocs that destroyed Nazism. This was very unusual in both cases but particularly Wolf's. There weren't a lot of Jews in the upper reaches of the East Bloc but he pulled it off with aplomb. (This doesn't have to do directly with him being a Jewish intellectual but just look at pictures of Communist higher-ups in his memoir from the everywhere except Cuba: 29 of them look like a boiled potato in huge glasses and an ill-fitting suit, the 30th is Markus Wolf, who looked like a movie star till he turned sixty.)

He's the son of a good-but-not-great Communist intellectual and writer; grows up in Moscow with every reason to support a communist Germany; basically founds East German foreign intelligence and runs it for the duration of the DDR state; his brother Konrad is the leading art film director in East Germany (in part thanks to the artistic freedom that comes from having a brother like Markus); he is by far the most effective East Bloc spy chief and places agents everywhere including most famously Willy Brandt's chief of staff Günter Guillaume (Brandt was forced to resign as Chancellor when the secret was revealed); he's known for decades as "the man without a face" because western intelligence can't get a photo of him; he strongly supports Gorbachev as against the old DDR Stalinists to the point of resigning his office in the 80s; he actually addresses the half million-strong pro-democracy rally at the Alexanderplatz in the name of reformed communism (the video of the crowd realizing who Wolf is and starting to boo him is one of the most electric moments on Youtube; Bärbel Bohley says that when she saw Wolf's hands shake while he was giving his speech she knew the regime was doomed); he avoids jail and becomes a weird media celebrity, publishing a (genuinely good!) literary memoir of his Weimar Berlin to Moscow childhood, a sort of potboiler spy memoir co-written with an Economist correspondent to pay the bills and... a Russian cookbook.

John le Carré claims that Karla (and Fiedler from the Spy Who Came in From the Cold) aren't based on Wolf but that's obvious bullshit. We know from manuscripts that Fiedler, the sympathetic intellectual Jewish East German spy, was originally named Wolf. If le Carré happened by chance to name his fictional East German Jewish spy-intellectual after the only real East German Jewish spy-intellectual, that would be an amazing coincidence.

As for Karla: le Carré disliked Wolf the post-Cold War media figure and called him morally equivalent to Albert Speer. This may be true! But Le Carré's fiction is full of Russian and German apparatchiks who are supposed to be as morally ambiguous as his literary English spies. If there was anybody like that, it was Markus Wolf. Karla is based less directly on Wolf than Fiedler because Karla is Russian and non-Jewish, but Karla still has many of Wolf's personal and professional characteristics.