Dear Friends,

I’m sharing an in-no-way topical or relevant discussion of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. The idea with posts on books or movies on this Substack is less to offer some kind of a review than to engage with a work as something like a friend. This post is also on

.Best,

Sam

TINKER TAILOR SOLDIER SPY

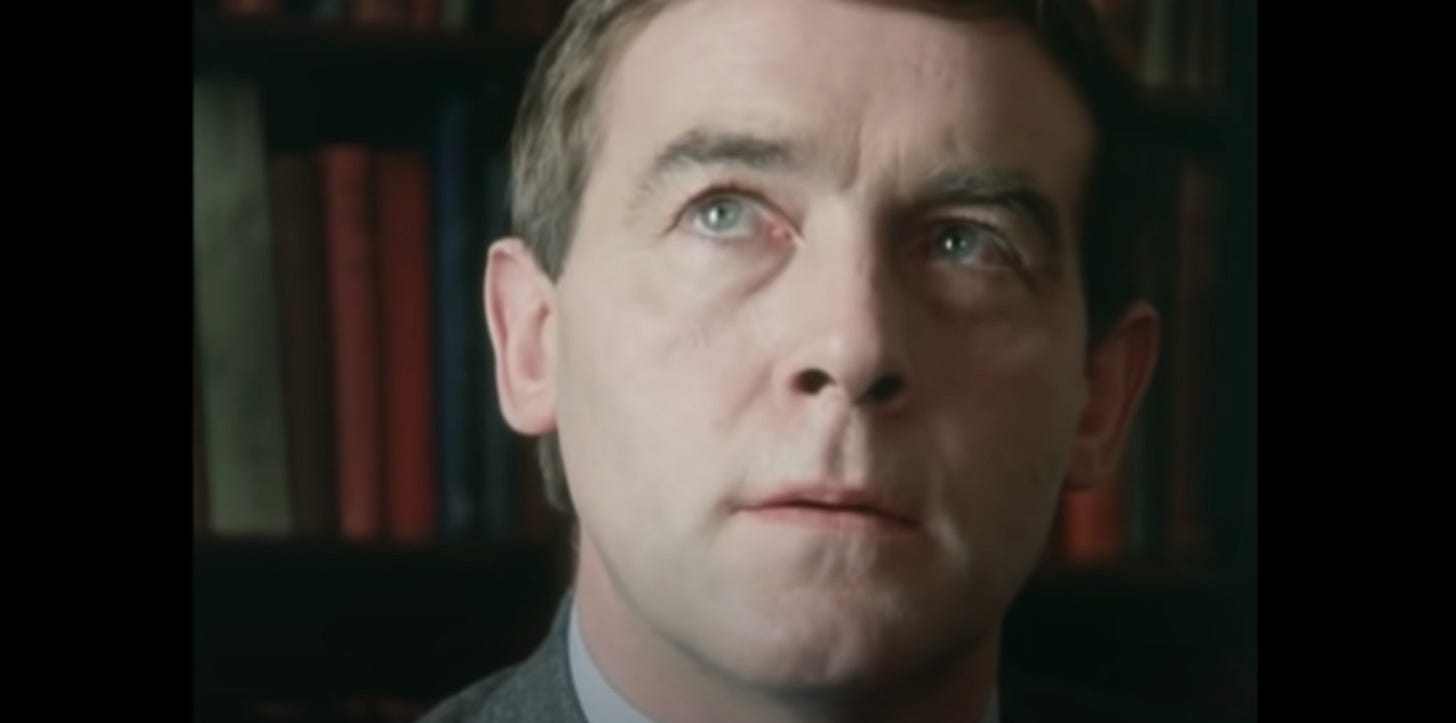

I had a sleepless night this week and at a certain point there was clearly nothing for it but to watch the entire seven-part Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (the BBC show from 1979, not the movie remake of 2011).

This is not the first time this has happened, and it made me wonder what it was exactly about this show that seemed to be the only tonic for certain kinds of moods. By the way, if you haven’t seen Tinker Tailor, you probably should stop reading, pour yourself a sherry and watch the entire seven episodes before returning to this post. I’m trying not to have any too-direct spoilers, but I’m writing assuming that you know who the main characters are.

Tinker Tailor is famous for being a spy story that’s not really a spy story — everyone has their roles to play in a (really knotty) Cold War drama, but as the story opens out to take in all the ancillary characters, and slows down (The Washington Post described it as “madly atmospheric”), all these different lives get caught in outline and the real subject turns out to be the psychic toll of service. As a YouTube commentator writes, “Tinker Tailor is as much about bureaucracy as anything else.” That’s a reasonable way to put it — and places the show in the company of The Wire (another breakthrough in television drama, which, not coincidentally, showcased the ability of a procedural to, instead of focusing on the crime, focusing on the bureaucracy and the ways that bureaucracies cripple everyone associated with them). When I first saw it as a teenager, Tinker Tailor became one of my very first glimpses of what adult life — and the “trenches” of the workplace — were really like, and a great deal of it has only became clear to me more recently. It turns out that, even within the high-stakes procedural drama, Tinker Tailor isn’t exactly about catching a spy. It’s about how vendettas, greed, cliques can rot out an institution. In narrowing down the mole to a handful of suspects, George finds that they are all, in a real sense, guilty — one is overtly working for Moscow Center but the others are pulled into the conspiracy and are invaluable to the mole’s machinations. I think I must have watched the show three or four times before I understood what all the endless fuss about Merlin and Witchcraft was really about. As George puts it, “Ever bought a fake picture? The more you pay for it the less inclined you are to doubt its authenticity.” In other words, as people move up the greasy pole, as they become wedded to their ambitions and to their bureaucratic domains, it becomes almost impossible to retain any sense of integrity or intrinsic worth. Corruption — Tinker Tailor emphasizes — is almost wholly inextricable from adult life.

But, fittingly, there are wheels within wheels, and in some higher sense, Tinker Tailor isn’t about bureaucracy or corruption any more than it is about catching the mole. What it is really about — I believe — is waste. And, for me, since pretty early adolescence, this has been a very particular aesthetic taste — I find myself moved when I come across it more than I am by anything else. It’s in the third act of Our Town, it’s in Forrest Gump, and Tinker Tailor is riddled with it. This is the real meaning of every one of the interviews that George conducts — with Connie, Sam, Jerry, Jim — each one “madly atmospheric,” each one ripe for ruthless cutting in any more conventional TV show. We really do get a lot of Connie’s tutoring schedule, of Sam’s croupier job, of Jerry’s bar bill — everybody in the ruins of their own life — and we understand, at some point in the conversation, what went wrong. Somewhere or other, every one of them dedicated themselves to an ideal — Connie, Jerry, and Sam sticking their neck out for some piece of intelligence, Jim devoting every part of himself to the service — and every one of them ends up with absolutely nothing to show for it. From a plot perspective, the summa of the ‘Karla Series’ comes at the very end of Smiley’s People, George through a lifetime of patience, tradecraft, emotional repression, an unendurable psychological toll, lands the big fish and mutters to himself “oh my dear god,” but the moment of redemption and fulfillment is understood to be a vanishingly rare event and is not available to Connie, Sam, Jerry, Jim, or any of his other dozen or so other interlocutors. Far more common in the world of Tinker Tailor is the moment when it all goes up in smoke — Control sitting in his office on the fifth floor, hearing that his desperate operation is blown, that the mole has beaten him, and his lifetime of patience, tradecraft, emotional repression, etc, is all for nothing, and that all that’s left to do is get himself a cab and go home.

What exactly is being conveyed in these long shots? Control on the fifth floor, the muscles in his face starting to spasm. Jim sitting in the pews of the school chapel where he is now teaching, shaken despite himself by a Bible verse. Connie in her shabby apartment talking to her dog Flush after everyone else has left the room. It’s a glimpse of what real dignity looks like. It’s a lifetime with nothing to show for it — if the mole hasn’t directly undermined each of these people, then petty rivalry, bureaucratic intrigue, have — but, somehow, each of them is potent in their own way, much in the way that Forrest is potent sitting at a bus stop all day with nothing better to do than wait for his son to come home from school; that Mother Gibbs is, after a lifetime of selfless and upright conduct, to, with perfect composure, tell Emily that “our life now is to forget all that and think only of what’s ahead.” It’s very different from the look that the heads of the Circus have when the mole is uncovered and their unwitting part in his activities revealed: that’s waste of a very different kind, the kind that nobody (least of all these venal civil servants) can possibly look at honestly in themselves.

If Tinker Tailor is a monument to this sort of unheralded, unrewarded dignity, what it is not is idealistic. It’s never really clear if George is fighting ‘for the good’ or not — as Connie puts it in Smiley’s People, “it’s grey, half-devils against half-angels.” George’s more sophisticated interlocutors are of the belief that George has a residual schoolboyishness, an antiquated patriotism, with no resemblance to the world as it actually is. As the mole says when he’s caught, “The Circus talent spotters, they picked us when we were golden with hope. Told us we were on our way to the holy grail, a lifetime of glory ahead of us —” and then breaks off into a mixture of tears and laughter. “It was necessary,” he continues, for somebody to see past those illusions, for somebody to exercise a real inner freedom, to navigate the rockier shoals of venality, of the real world, without some illusory guide like schoolboy patriotism. Various characters within Tinker Tailor — not least George’s wife — become convinced of the essential validity of this way of thinking, that it actually represents a higher ideal. As Jim puts it, “ you can’t judge him by things like that he’s got different standards.”

And, actually, Tinker Tailor offers no real rebuttal there. It’s far from clear within the context of the show that ‘The West’ is any better than the alternative, that Britain is a cause worth fighting for, that “the wretched Cold War” offers anything beyond “technical satisfactions,” as George puts it, for those playing the game of it. All of George’s interlocutors seem to have learned, from the experience of a lifetime, that the best thing is “to get a bit of love,” to “devote oneself to the profession of forgetting” — that there’s not much to be said for causes, except for the dignity that they generate and the curious light that they cast.

Every time I’ve watched Tinker Tailor there’s been something that arrested me about the Peter Guillam character and this time I think I finally sort of got it. Guillam is, along with Tarr, the closest analogue in Tinker Tailor to a conventional movie-ish James Bond figure. He drives fast cars, is adept in ‘wet work,’ does ‘tough guy’ courses in martial arts, but his life isn’t that. The nearest he comes to real clock ‘n’ dagger secret agent work is to steal a file from a library. He finds himself in middle management — his evident stylishness not at all a barrier from the withering disdain of his superiors. And, contrary to the cool guy vibes that might be expected of him, Guillam leads with class snobbery — is tongue-laceratingly sharp with Tarr and Fawn. There’s something in the Guillam character that makes it clear how the British Empire really ran itself — Guillam was, as Connie puts it, one of the “poor loves who was trained to empire, trained to rule the waves” — and it was done not really with merit or bravado but with a microscopic attentiveness to status. But Guillam, compared with the other sons of empire, is in a more equivocal position. George, Bill, even Control, are sustained by a vision of halcyon days — it’s one of the more evocative points that the buildings of Cambridge University are used for the episode credits. “We used to be rather a classy bunch, how did we turn so vulgar?” asks Bill. Peter has no real memory of that. His hero turns out to be a traitor. His experience of the service is of endless bureaucracy, constant politicking — “you had all the qualifications for dismissal,” George says to him, “you were good at your work, loyal, discreet.” And yet Peter continues assiduously in his work and does well enough at it to earn a brief, awkward pat on the back from George — “you helped tremendously.” What is it exactly that sustains him? It seems, as far as I can tell, to be a burning inner rage. As Michael Jayston plays the part, Peter is constantly seething, constantly on the verge of some act of violence or other. The older, sager Mendel believes that he’s wired too tight — “one of the tough ones who crack at 40” — but George believes in Peter and the rest of the story bears him out. For Peter, what seems to matter is craft — he has to be good at what he does, whether he’s working for the Circus or for George’s renegade band. His explosion at Percy — “I haven’t seen him! Who’s playing games? Not me, you are. So get off my back!” — is one of the better moments that any subordinate has ever had on television, and seems to be deeply, profoundly felt, no matter that Peter is lying through his teeth. For Peter, there is an endless pride in what he does — and if he keeps slipping through the cracks professionally, keeps running afoul of the leadership structure, that is, in some important way, no hinderance to his sense of self. It becomes possible to carry oneself with dignity in a sort of vacuum — to do work adeptly, even ferociously, with no idea what it’s for, with no idea whether it will pay off or not.

Now I wish to do engage - because it’s a hot, humid night in New England perfect for marathon viewing or certain kinds of 📚