People who have been reading this Substack for a while are likely to be tired of a point I make pretty frequently, but since every so often I like to pretend to be an oracle I can be a little less than clear and it seems like I should try to explain as simply as I can what I mean.

The idea is that the fundamental human activity, basically, is to assess worth, to assign value. To put it toolishly, if we think about Maslow’s hierarchy, we find this easy enough to do at basic levels — we generally prefer to survive than to be killed, we like to ensure our reproductive survival — but harder as we move up the pyramid and as we engage with society at large.

In most societies, at most points in time, there has been considerable diversity about what confers value. Mircea Eliade describes the division of the sacred and profane as a fundamental organizing activity in society — on the side of the sacred (in the temple, in ritual, etc) there is higher worth but, certainly, the profane, with its attention to daily life, has its right to exist as well. In the Middle Ages, according to a widely-popular schema, society was divided into ‘those who fight, those who pray, and those who work’ — and each of those had their own unassailable claim to value. In Jan Potocki’s altogether wonderful The Manuscript Found in Saragossa, which takes in the energy of an 18th century travelers’ conversation, the various interlocutors propose to one another their vision of a good life — some are more pious, some are more hedonistic, but pride of place seems to go to the path of honor. As Alphonse, the principal character puts it, “I could not imagine any sounder basis for virtue than a path of honor, which seemed to me by itself to contain all the virtues.”

The history of the world since then has, basically, been a winnowing away of all the other means of assigning worth, leaving only lucre. As everybody knows, piety has, in the West, on a mass scale, generally lost its hold over people’s imaginations as a means of assessing value. The ‘path of honor’ gradually disappeared as an ethical system to the extent that saying it now sounds like a joke.

The rise of lucre as the means of assessing worth can be understood historically and materially. Money, of course, always existed, but money was, essentially, an unstable means of social exchange — one’s purse or treasure chest could always be stolen, one’s land could always be pillaged. With the early modern period, money became a far more stable entity — modern banking provided a degree of protection for wealth that no other economic system had provided, and with the gradual breakdown of the aristocracy and emergence of a bourgeoisie, money became increasingly convertible to social status. Markets — which nobody had really bothered to think all that much about — were revealed to be highly-intelligent, maybe (per the school that follows from Adam Smith) the sole efficient way to organize societies at a vast scale, and a remarkably comprehensive metric for evaluating worth.

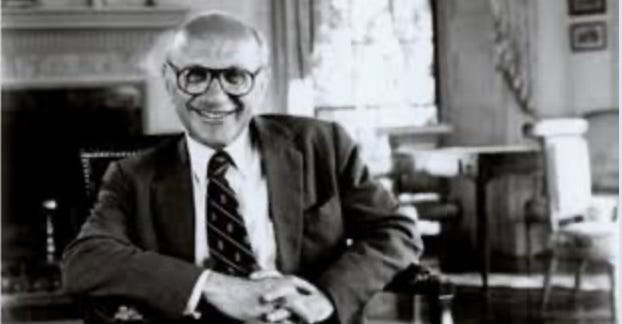

The apex of this way of thinking may be Milton Friedman’s idea of ‘shareholder ethics’ — the ethical system that we all live with. This is very different from the ethical system that, say, the medieval Catholic Church promulgated, and, with it, lucre becomes not just a necessary evil but actually the heart of ethical action. A human being’s worth is in maximizing profit. That profit leads to all kinds of societal benefits — creating jobs, creating fluidity in the market, which creates wealth in the society-at-large, etc.

Against this doctrine — very rational, surprisingly hard-to-argue with — there are two loci of resistance. One is the state. The other is art. The state, curiously, is the one institutional entity that resists the inexorable logic of markets. From the perspective of, say, the Middle Ages this wouldn’t have been entirely obvious. The state at that time could be understood as an economic entity, a protection racket, with the state offering employ, basically, for a class of professional fighters. At moments like the Thirty Years War, any notion of a benevolent state seemed to disappear altogether and mercenary armies just chased each other around while looting the countryside in the meanwhile.

But as capital stabilized and wealth shifted from the land towards various financial instruments, the state began to conceive itself as something very different — as a benevolent entity offering a countervailing force to the market. Our vocabulary now differentiates sharply between the ‘private sector,’ which is dedicated to shareholder value, and the ‘public sector,’ staffed by ‘public servants,’ who are expected to work for a fixed salary and to selflessly serve the common good.

It’s a nice idea, but, as everybody knows, it doesn’t really work. First of all, the state can’t really be all-sustaining, as was the idea in the early 20th century social democratic and totalitarian states — there isn’t enough real work to go around. The trend since then has been for the state to offer a limited number of protections and services, to be something like the ‘house’ in the casino. And then the state has its own capital projects, which require turning to the private sector and falling into the same monetary values as everything in the private sector. What is important, though, is that the military does not just follow its market worth — and here, in the almost quaint sense of duty that fighting people have to their nation, we have the real value of a state: creating a nationalist sense of worth that is distinct from the worth of money.

The other locus of resistance is art. As far as I can tell, there was never any particular sense of art as a distinct realm or of art being in any way in opposition to the market until the Romantic Era, when a new philosophy emerged by which art came to be seen as antithetical to the market and, really, as a substitute for fading religion. This view reached its apogee in the dizzyingly anti-utilitarian formula, “art for art’s sake,” which makes no sense really unless you see it as art carving out a domain for itself distinct from commerce and arrogating to itself the privileges earlier reserved for religion — the caretaking of the human soul and the determination of transcendent value.

But art, too, was beaten. Art’s weak point was its dissemination, and as art became hooked up to mass media — whether in big-budget cinema or, more inconspicuously, the distribution of text by a ‘publishing industry’ — art increasingly lost its bargaining position vis-à-vis commerce. The rebranding of art as ‘content’ or as a ‘creative industry’ signaled the final assassination of the Romantic project; I think I felt its death-blow when I opened a book on ‘creativity’ and read a description of how carefully Disney had organized the architecture of its offices so that the ‘creatives’ would be free to dream in any way they wanted and then to hand off to their ideas to the plebs in the production line. That takeover is almost entirely complete — with the ‘success’ of a work of art being determined by its market value, by its ability to earn back an advance for its publisher, or to enter the bestseller list, or to make millions when sold at an auction-house, or to have the muscle of a Hollywood studio behind it and reach a mass-market. Anything else is the ‘avant garde’ or the ‘fringe’ or, more simply, ‘failure.’

That is the state of affairs we find ourselves in — with money, through its astonishing capacity of converting itself into different forms of value, coming to stand for all worth. And it would be satisfying and rational — but you can insert whatever song lyric or proverb you like to argue against this. “The best things in life are free,” says Dinah Shore. “Money get away,” says Pink Floyd. “Mo money mo problems,” says the Notorious B.I.G. The Greek myth tells the story of the king who was so afflicted by his golden touch that he couldn’t even hold his daughter or bring food to his lips. Family relations are, of course, almost perfectly resistant to money — money has nothing at all to do with the love between a mother and child. The value of money tends to recede drastically in people’s posthumous reputations — which is, to a great extent, what people care most about. And, as the much-debated proverb has it, “money can’t buy happiness.”

Meanwhile, money has, in the public sphere, been committing a few surprising acts of suicide. Financial instruments have been becoming so sophisticated that, like an illustration of some Biblical proverb, they have all-but-disappeared into vanity — so that wrapped securities, national debts, leveraged buyouts, etc, often seem to have no relationship to backed currencies at all. And if the valuation of worth in the public sector had long been income, the internet, via the ‘like’ button, produces a curious surrogate, almost exactly like a token in an amusement park, which is nonetheless increasingly convertible to a person’s social worth without having necessarily passed through money at all.

So this is where we really are. Money seems to have a total grip on our ability to evaluate worth, but money isn’t actually convertible to the most important things in life — to our family relations, to our posthumous reputations, to our integrity, to the state of our soul — and money turns out to be a more fragile source of value than many of us might expect. What money is, more than anything else, is a trick of the mind — an exchange in which both parties in the transaction choose to believe in a magic trick. If that faith in money’s value can be inculcated, it can also be withdrawn — and the social work that we have to do, I believe, is to have the scales fall from our eyes on certain aspects of money’s worth. If money promotes some book or film, wraps it up in publicity, disseminates it widely, starts having meta-debates with itself about how the ‘influence’ of that work proves its underlying quality, that actually goes no way at all to demonstrating that work’s worth. This is not to say that money isn’t a useful instrument — the exchange of cash for goods and services in the market is generally better than the older, clumsier systems of barter — but, when it comes to things like works of art, or acts of expression, or the evaluation of one’s own character, money is all but useless. And here the system of conversion is completely different. What we are really looking at (or should be) when we look at, for an instance, a work of art is the extent to which it represents the operation of that artist’s soul. A number of old-fashioned words come back into play — ‘honor,’ ‘virtue,’ ‘character,’ ‘integrity,’ ‘glory.’ All of these stand for real things, real ways of evaluating a person’s worth, but they might as well not exist in an era where all social value is convertible to lucre.

And I'll add Gillian Welch's "Everything is Free Now" ("We're gonna do it anyway / Even if it doesn't pay")

I would love to see a series of Substack writers complete this sentence: "What we are really looking at (or should be) when we look at, for an instance, a work of art is ____." Soul is part of it, but what about the Oversoul?

Great work.

Practically, though, how would you incentivize fellow citizens (or as part of a “benevolent” State) to care about their interpersonal relationships and posthumous reputations in their day-to-day lives?

Seems to me that kind of reflection, which someone like you can so elegantly share with great care, is a stretch for most sapiens, especially if we’re neck deep in a rat race that’s so ingrained in our biology most of the time we’re not even aware of it.