Dear Friends,

I’m sharing the ‘manifesto’ of the week - some thoughts on intellectuals and courage.

I’ve turned on the paid feature for subscription - and am grateful, of course, to anyone who is able to upgrade their subscription.

Best,

Sam

WHAT IS AN INTELLECTUAL?

One of the odder surprises for me in first leaning 20th century history was the number of times that the state or the state-orchestrated masses turned viciously against ‘intellectuals.’ It was a theme of Pol Pot’s Cambodia, Mao’s China, Stalin’s Russia, Hitler’s Germany, of right-wing movements in Europe and the U.S. This always particularly struck me because the intellectuals I knew seemed so pleasant and unworldly, a very unlikely target for tough, murderous police regimes to set themselves against - a bit like the powers-that-be deciding that public enemy number one was hermits or vegetarians.

This struck me also because from just about from the time I first heard the term - it was connected in my mind with the delivery of The New York Review of Books, which I found to be a weirdly rapturous experience - I was sure that that’s what I wanted to be. I found it difficult to imagine a profession that seemed to be, all at the same time, so peaceable, high-minded, consequential, and really was taken aback when I discovered that just about nobody shared that conviction. In Kundera’s The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, a woman is livid that her boyfriend ‘makes love to her like an intellectual.’ In op-eds, the intellectuals - sometimes manifesting as the ‘chattering classes’ or the ‘nattering nabobs’ - were blamed for just about everything, a very perplexing development since everybody I knew who fit that description seemed capable of talking only about how they had no money and no power.

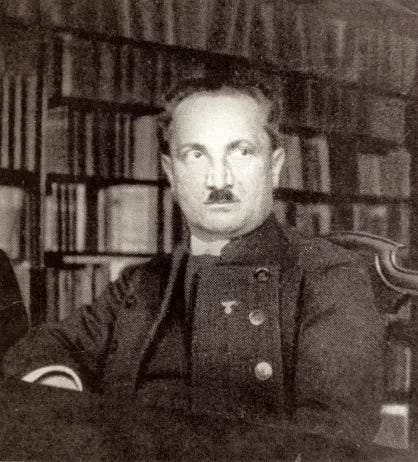

But the next level of education was to discover that, actually, there was something to the critique - that intellectuals weren’t quite so benign as I had supposed. The reason all these totalitarian leaders were so fixated on the destruction of the intellectuals as a class was that they themselves had been intellectuals and assumed that that was the most dangerous direction of subversion. And not only were so many of the totalitarian madmen intellectuals - at least to the extent of writing books and developing theories - but they all seemed to have these prominent in-house intellectuals as well, Evola, Ilyin, Breitbart, Haushofer, Schmitt, etc, people who were serious, dedicated intellectuals in the sense of believing in the power of ideas and in the life of the mind and who had, either from heartfelt conviction or raw cynicism (and it was hard to decide which was worse), put all of that philosophical apparatus in the service of lunatic or diabolical regimes.

They were a very strange species, these intellectual enablers, the high-brow servants of thugs, and other intellectuals seemed to pour all kinds of energy into analyzing them. There was always something a bit hard to understand in the attention that had been devoted, ever since it happened, to, for instance, Heidegger’s affiliation with the Nazi Party. For the intellectuals and historians who swallow this particular bait - and I’ve also been very interested in these sorts of questions - there’s a great temptation here, which is to believe that history is ultimately rational and occurs in the realm of ideas and, presumably, that a virtuous and prescient intellectual can nip a dangerous idea in the bud so that if, say, Husserl or Cassirer had outargued Heidegger at some pivotal conference in the ’20s then Hitler might never have happened in the way that it did.

A surprising amount of pop philosophy and pop history is sold under this premise, and I do think there is some truth to it - that, as Breitbart famously said, “politics is downstream of culture,” and the wars of ideas tend to occur before the actual shooting. However, the evident wistfulness with which intellectual historians write about Heidegger or Schmitt or de Man tends to give the game away. It’s not really as if somebody like Heidegger or even Nietzsche laid out a philosophical blueprint that Hitler then followed. As it turns out, deranged men of action, like Hitler, are perfectly capable of coming up themselves with self-serving philosophies of power, and so a great deal of this sort of high-stakes intellectual history, e.g. Heidegger in the Nazi era, is revealed on closer analysis to be less about ideas and more to be the embarrassing story of how these high-wattage philosophers proved, when push came to shove, to essentially be hacks and courtiers, fixated on getting as close as they could to power.

Now, when people talk about ‘intellectuals,’ this, increasingly, is the idea that comes to my mind - of the highfalutin hacks, op-ed writers and think tank spin doctors, who are able to turn ideas into some sort of politically reliable currency, ‘intellectual capital’ being the apposite phrase.

The disasters of the 2010s - the advent of the tech dystopia and the extreme polarization of left and right - resulted, for the most part, from not thinking at all, but they were also, to some extent, intellectual failures. A whole set of people who were trained to be, and paid to be, voices of conscience for society-as-a-whole, simply lost their ability to think critically and independently. This was true during the coronation-of-Hillary when liberals fell into a certain lockstep orthodoxy and failed to even comprehend that the country was undergoing a massive shift in political sensibility that needed to be taken seriously; it was true when the liberal center accepted progressive identity politics as a normal or even quaint iteration of politics-as-usual and failed to understand the extent to which freedom-of-expression and freedom-of-debate were crumbling within ostensibly liberal universities and media outlets; and it was true when mainstream intellectuals continued to treat tech and social media as basically frivolous long past the point when they had fundamentally transformed the social landscape.

I’m not saying any of this to - primarily - blame anyone. There a few prominent intellectuals of the era who are already looking very bad - Malcolm Gladwell, Michael Lewis, Yuval Noah Harari, etc, who in their different ways were cheerleaders for dataist and tech-driven modes of thought; Judith Butler, Robin DiAngelo, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Ibram X. Kendi, etc, who advocated for a militarization of daily life and for wildly over-the-top responses to essentially minor social infractions. But this is a really complicated period. The Internet and social media together are creating a social landscape for which there is no precedent in human history - and anybody attempting to deal with it intellectually is left grasping for models. For those looking to follow the bouncing ball, there are really only a handful of thinkers - as far as I can tell - who’ve gotten any sort of handle on what’s happening. These are Gilles Deleuze, Jaron Lanier, Byung-Chul Han, above all Martin Gurri. What they have in common is a focus on modes of discourse, an understanding that communication itself has become so dramatically different as to make just about any analogy-driven analysis irrelevant.

The class of people who are really cruelly exposed by the shift in modes of discourse are the hacks. These are the pollsters who were so badly ambushed in 2016, the predictable voices at the party rags, the professorial milquetoasts, all of whom could skate by for decades in more normal political periods but find themselves without any real ground to stand on as the old center pulls apart. To name names here, I’m thinking of kind of the whole NPR cohort, the critical mass of The New York Times op-ed page (Maureen Dowd, Gail Collins, Charles Blow, Ross Douthat, and now augmented by Michelle Goldberg and Zeynep Tufekci), and so on.

And what a period like this reveals is who the public figures are who actually have the courage of their convictions, who are able to follow the progression of ideas as they move through the society, and who are able to take some sort of a stand - in other words, it helps to clarify what the function of an intellectual is. And to follow that line of thought the critical intellectual at the moment is

. She had a position that any hack could have happily nursed for a long time to come - bringing a modicum of intellectual diversity to The New York Times’ op-ed page. But Weiss quickly came to feel that the position was purely cosmetic. She couldn’t publish actually contentious, strong-willed pieces without running into the teeth of a censorious editorial board and narrowly partisan cubicle culture. So Weiss quit - and, in quitting, produced two remarkable documents, an open letter to A.G. Sulzberger critiquing The Times’ abrupt turn to illiberalism, and a broadside in Commentary critiquing a culture of cowardice among the intellectual class. “If cowardice is the thing that has allowed for all of this [i.e. the insanities of wokeism], the force that stops this cultural revolution can also be summed up by one word: courage,” Weiss wrote. “And courage often comes from people you would not expect.”, Weiss’ Substack and contribution to the woke wars, amounts to a series of profiles of courage of individuals who have made similarly quixotic decisions to bail out on high-status positions out of protest at the curtailment of freedom of expression. (The site features missives from a Levi’s brand president, a UCLA professor, various people with great-sounding jobs who quit and then took to Substack.) And if this can get a little tiresome, its own form of kitsch, it, to me, epitomizes what it means to be an intellectual at the moment. It’s not just about having opinions, trafficking in ideas, articulating them eloquently. It’s about taking some kind of a stand and putting one’s reputation on the line for it. In the end, that’s what being an intellectual is and why so many regimes have regarded it as such a dangerous pursuit - not just that ideas have currency and a life of their own and a way of bucking coercive pressures, although that’s part of it; it’s that a real intellectual has beliefs and is willing to stand for those beliefs at personal cost, with the result that an intellectual becomes a threat not only to the status quo but to the power of conformity itself.

Great article. I'll pass it around. Was going to upgrade to paid but Substack collects too much information. Thanks anyway.

Thank you for this.