Dear Friends,

I’m sharing a discursive essay with some thoughts on art and representation.

Best,

Sam

TWO WAYS OF THINKING ABOUT MODERNISM

All the artsy people in my life seem to beset by an underlying, vexing question, which, in a word, is: why does art now suck when about a hundred years ago it was very good? Or to put it less insultingly, why does high art in our era seem not exactly to hit, not to affect the center of the culture where, once upon a time, T.S. Eliot was selling out sports stadiums and waitresses were fighting each other for the sketches that Pablo Picasso doodled on his napkins?

I’ve had two ways of thinking about this, and, over time, have shifted from one to the other. When I was younger, I was an aestheticist. I believed that cultures had a center to them and that a work of art, pitched in the right way, would inevitably hit the center, would be instantly recognizable and irresistible to the collective psyche. The understanding was that modern art had met that criteria, that, if the initial reaction (particularly of backwards-looking critics and curators) had been horror, a visionary artistic vanguard together with a surprisingly broad-minded criteria had been willing to embrace the new. Art criticism, then, involved working backwards from that, trying to understand what it was about the Impressionists or the Cubists or the Abstract Expressionists that had been so resonant.

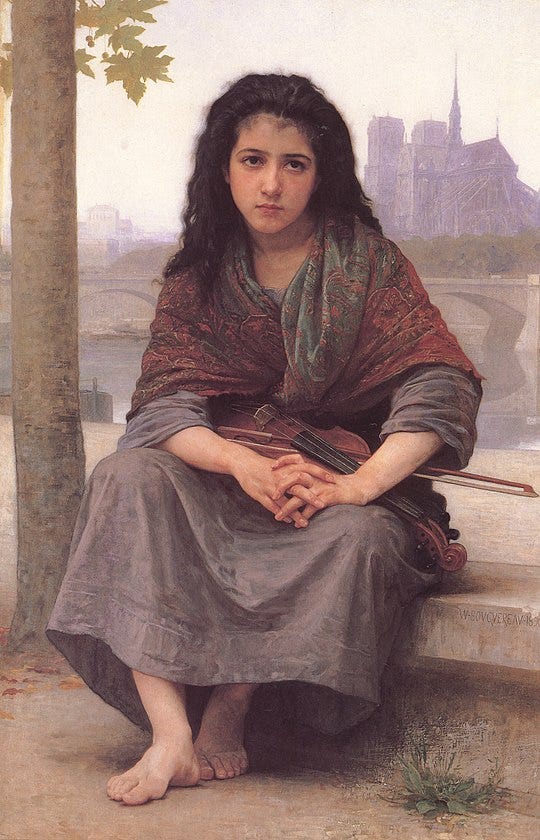

And, at one point, I thought I had the theory that explained it. The idea was that it became clear, through the 19th century, that various arts, but particularly painting, was coming under existential threat from new technologies. Western painters had, across a rich, centuries-long tradition, learned to mimic the outside world with startling verisimilitude. The ‘backwards’ painters of the 19th century (the ones who would be decried by the Impressionists) were really just bringing those naturalistic techniques to new heights. But the more forward-looking figures of the era discerned that that, really, was a dead end: for one thing, it removed imagination from painting and involved just an ever-unfolding succession of more precise techniques; and, for another, machines were coming and could do with the click of a button the same thing that highly-skilled painters had labored for centuries to achieve.

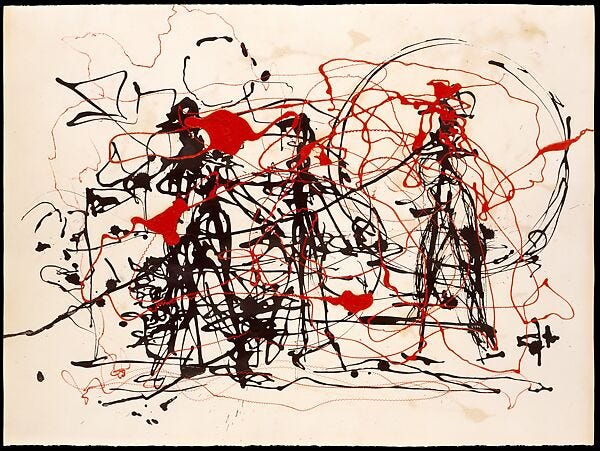

The intelligent move in that circumstance was to disown the entire field of naturalism and representation, to shift the entire conception of art into a realm that only artists could access and that would be unattainable by machines in anything like the foreseeable future. In my art history education, this shift had occurred in three or four distinct stages: with the Impressionists and a move towards the subjective perspective (how does, for instance, the Rouen Cathedral look to a particular viewer at a particular time of the day); with Van Gogh and a move towards the visual plane as an internal imaginative object (Starry Night); with the Cubists and a conceptual reordering of the visual plane; with the Abstract Expressionists and an abandoning of representation altogether. Seen as a totality, the entire century-long movement comes across as a scorched-earth tactic, finally reaching a place that photography, however good, couldn’t access. (At which point, also, painters seemed to reach their own dead end, and, from their sanctuary in abstraction and high-end conceptual theory, to make forays back into the world of representation.)

All arts, by the way, went through a similar journey in the early part of the 20th century, but the intensity of painting’s repudiation of itself goes some way towards bolstering my thesis. Writing, for instance, has been under threat from cinema for nearly the same period of time and has worked out its own flight into interiority and modes of expression that movies couldn’t touch, but, for painting, the threat was most immediate and palpable — and painting went the furthest the quickest in articulating some new aesthetic.

As for why visual arts seemed to have lost their centrality in public consciousness, my belief was that the visual arts had to some extent lost contact with what they were looking to do. That the great movements from the Impressionists to the Abstract Expressionists were closely in touch with the resources of their medium in contrast with the advancing force of technology, and if the public-at-large didn’t always immediately understand the modernists’ work, they respected the intensity of it, and learned to trust leading artists to get at the real truth of their forms while negotiating with their eras. From postmodernism on, the artistic community seems to lose contact with the public-at-large. Avant-garde poets do not sell out stadiums; the public rolls its eyes at whatever the artistic community is generating. The feeling, simply, is that around the time of Warhol the art world ran out of ideas; and also lost the courage of its conviction in really driving a new ‘way to see.’

That sensibility places the emphasis on the artists: if artists can figure out the truth of their culture at its particular moment in time, that thinking goes, then, however crazy the work may seem to be, it will resonate with a wide public. But, recently, a more cynical perspective has come to take over more of my thinking.

That perspective is encapsulated in Hugh Eakin’s Picasso’s War where the emphasis is all on art markets and on dealers and curators that nobody has ever heard of. In the history of modern art, the truly important figure isn’t Picasso or Matisse or Van Gogh. It’s a lawyer named John Quinn, who, in 1913, succeeded in convincing Congress to amend a tariff bill that had made the importation of modern art nearly prohibitive and, in so doing, created a new class of mid-tier American art collector, unable to afford Old Masters but willing to take a flyer on new work. The history of modern art, then, pivots on dealers rounding up art from Paris studios, connecting to a sort of vast friend group that was more than willing to play the part of charismatically iconoclastic madcap, and then ramming that artwork down the throat of an incredulous American public. The institutional legitimacy of things like the 1913 Armory Show and then, later on, the MoMA and Guggenheim, result in the American public’s being forced sooner or later to accept the brilliance of the strange new art while the high prices fetched by avant garde artwork in America has its reverberations in Europe as well, with critics finding themselves compelled to see the virtues of art that they might themselves have been skeptical about.

In that narrative, it’s really only a handful of extremely wealthy people, Alfred Barr, Peggy Guggenheim, Gertrude Whitney, who drive the taste for high modernism and its acceptance as a replacement for beaux arts.

By the 1960s, a very different system is coming into being. Instead of the flow of the market running from bohemian studios to high-end dealers to a handful of public-facing modern art museums, the market gets academically driven. The new MFA programs generate a middle-class lifestyle in which the height for artists isn’t making money from their art but teaching art — and with their work like an academic CV to get the teaching jobs. Art becomes in some ways a healthier, more self-sustaining profession, with a degree of academic credentialing and a university’s safety net, as opposed to being dependent on the whims of a handful of millionaires. But, as it so happened, the millionaires of the early part of the 20th century actually had pretty good taste and were in sync with innovative, cutting-edge artists who genuinely were pushing the boundaries of taste; while the academic model tended to produce work that was self-referential, safe, protected by a self-supporting and increasingly opaque academic community. If a new class of magnates entered into the art market in the ‘70s and ‘80s, they weren’t interested in public-facing museums or genuinely innovative work; they were interested in a steady set of aesthetic values as determined by academic credentialers and with the work itself treated like passive income, stashed in private collections or in climate-controlled storage units and sold after having appreciated in value.

In that climate there was in a sense no way for artists to really break through with innovative work. Anybody who did so — Banksy comes to mind — would have to deliberately operate entirely outside the system. And modernism comes to seem somewhat suspect. It didn’t really seize the imagination of the public. It just grabbed a few influential people at a moment in time when their self-interest aligned with a vision for creating public works.

So what do we do with this set of questions? Nothing much. Just understand that art is far more beholden to commerce than our art history textbooks let on; that the history of art isn’t necessarily the best ideas winning out; and, for people who are interested in finding work of real worth, it’s necessary to spread the net very wide, to take in the rivulets as well as the ‘mainstream,’ to take in art that’s forgotten in addition to the art that the market remembers.

My lodestone on how to think about the modern art market is Tom Wolfe's The Painted Word, this excellent essay is a perfect complement!

Missing: role of CIA using a budget of 200M (billions in today money) to promote abstract art as rival to nasty commie realism (prone to you know, protest things). No conspiracy theory: check stubs, correspondence, all now in public record. See Saunders, The Cultural Cold War (2000). Those “critics” you reference weren’t “trying to understand” the art, they were paid to make a narrative to fool the public.