The Non-Fiction Novel and the Outlines of a New Form

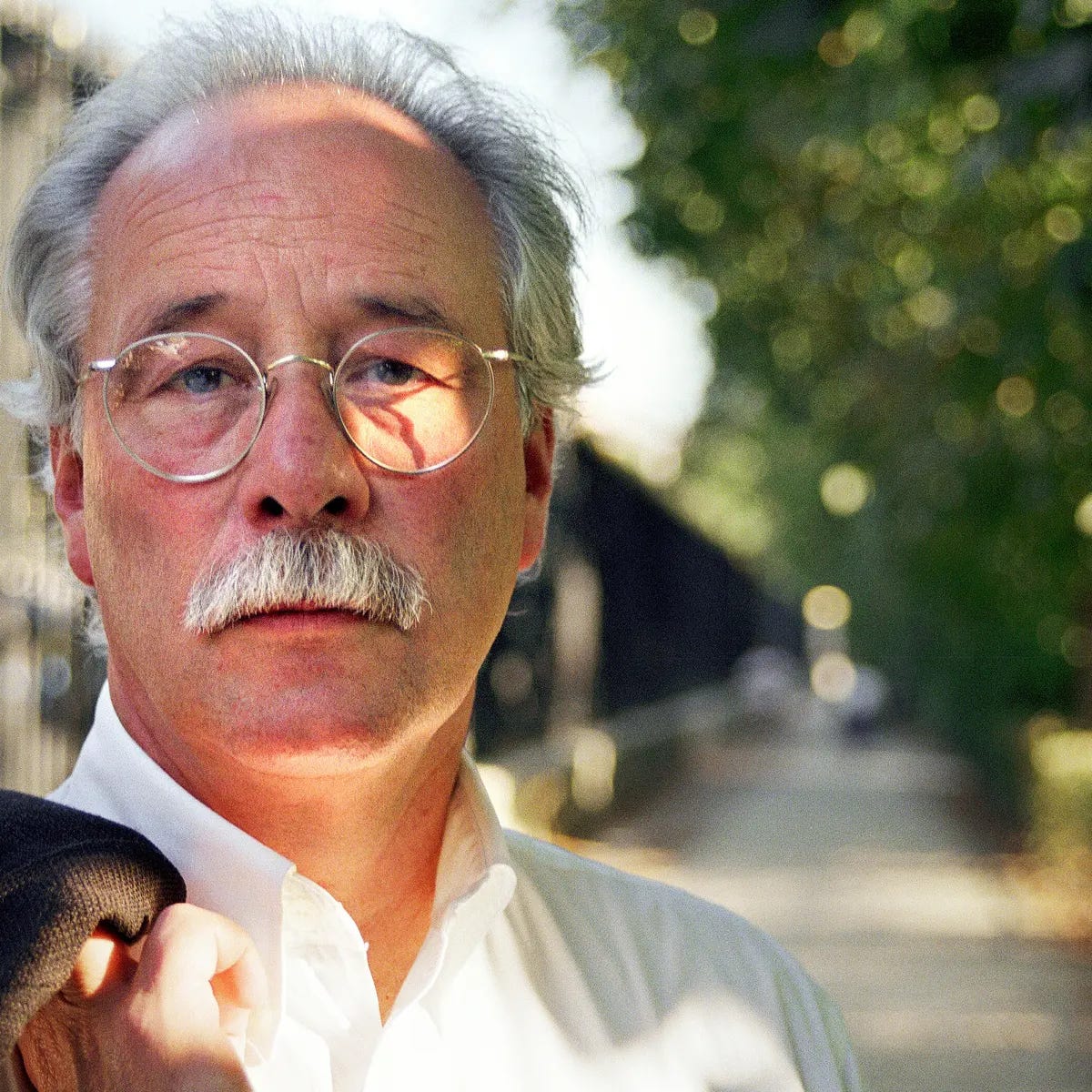

Benjamin Labatut, David Shields, Documentary v. Fiction

“I’m bored by out-and-out fabrication by myself and others; bored by invented plots and invented characters,” wrote the critic David Shields in his briefly influential 2010 manifesto Reality Hunger. “I find nearly all the moves the traditional novel makes unbelievably predictable, tired, contrived, and essentially purposeless. What I want is the real world, with all its hard edges, but the real world fully imagined and fully written, not merely reported.”

During its period of being passed around and frowned over, Reality Hunger seemed mostly just to confuse everybody – this was this guy’s problem? he didn’t like characters? he was overloaded with novels? And it wasn’t clear – probably not to Shields either – what he was hoping would supplant the traditional novel. It seemed like he was describing a formless kind of postmodern structure – something like what Nathalie Sarraute or Richard Brautigan were up to a few decades earlier – which the publishing industry, if not the literary hardcore, had pretty much given up on. Reviews of Reality Hunger – by James Wood, Michiko Kakutani, Stephen Emms – were equivalent to some old salt from the book industry putting their arm around Shields and telling him that yes, yes, he’s right about a lot but, basically, he needs to just calm down; and the problem with what he’s advocating for is that it gets tiring very fast, as just so happened to be the case with the overheated prose and stentorian itemized structure of Reality Hunger itself through which Shields seemed to be blueprinting some new form. “Somewhere around the halfway mark, repetition began to weaken rather than strengthen the rhetoric. It rang hollower than it had at the start,” wrote Emms. “I lost my appetite for reality hunger.”

But Shields was clearly impassioned by what he was saying, and that kind of conviction has a way of not only tapping into some cultural vein but of creating its own reality. And now – ten years later, with all the aesthetic trends discussed by Shields playing out pretty much exactly in the way he described them, the new art is just starting to come into focus, its features and limitations discernible.

***

The most obvious analogy to this is in visual media where documentary and ‘non-fiction narrative’ are actually starting to crowd out film featuring actors. This has happened for many reasons. The most obvious is cost. In the 2000s, television networks figured out that they could make ‘reality TV’ for a fraction of the cost of scripted programming. The math was pretty straightforward. Real people were cheaper than actors, they didn’t come with agents or managers attached, and they usually were happy to go on television for no money at all or for the chance at a ‘prize,’ they wore their own clothes and brought their own props, which meant vast savings on costumes, props, entire art departments. And, crucially, there was more impact – people watching television were happy to see (and to loathe) people like themselves who were suddenly, for no particular reason, vaulted into the center of the culture. Reality TV was of course ridiculously staged, but the people themselves were real, the emotions were insane but real, and it was possible for viewers to form very developed, very richly-felt opinions on the ‘characters’ in the same way that they would about regulars on a network sitcom but all the more so for not having to pass through the go-between of an actor. As Shields points out – I was actually shocked rereading this – more people voted for the American Idol finale in 2008 than voted for Barack Obama in the general election.

Reality is its own hybrid form, but it is composed out of the same base materials as documentary film (nobody wants to say that in documentary-world but it is true). Documentary for decades had been the weird step-sibling of film, generated by very broke, very obsessive people filming their subjects for years on end for a product that would be shown in some tucked-away art house theater. Terry Zwigoff, who made Crumb, probably the best documentary ever made up to that time, said he did so working for nine years on an income of $200 a month – and in a phase of his life when, he said, he spent every day working up the nerve to kill himself. But then, around the 2010s, documentary coat-tailed on reality to become profitable and for the same underlying reasons – low production costs, ease of connection with characters, fascination with the real. Documentary turned out also to be ideally suited to streaming – easily manufactured, easily labelable, and with a certain intimacy about it that rewarded laptop viewing. I work in documentaries and I’m stunned at the number of times when I’ve met people and said what I do and the reaction is “I love documentaries!” – especially since I sometimes say I’m a writer and the reaction has never once been “I love books!” Mostly, this annoys me, since a lot of documentaries’ appeal is that they’re informative, easily tune-out-able, and don’t require the same sort of sustained energy that art does. But I do get the enchantment of it. Every time I’m on a shoot and have gone through all the headaches of logistics and of production and the camera turns on, I feel a certain frisson – all this fuss for, usually, some perfectly regular person going about their day or chatting about their life; and there’s the uncanny sense that this, the shirt they happen to be wearing that day, the way their house happens to be arranged, can potentially be made immortal. And everybody seems to feel something similar – Tiger King may have been the last mass event that actually brought people together, just the sheer unbelievableness of everybody associated with the story. Free Solo was vastly more arresting than any fictional mountain climbing movie would have been (much more so, for instance, than 127 Hours). The low-key demeanor of Alex Honnold just before his big climb was real, the bitter tears of Sanni, his girlfriend, were real, the possibility of Honnold dying on camera was also very real – “it’s hard to not imagine your friend falling through the frame to his death,” said Jimmy Chin, Free Solo’s director, as part of the film, “and that’s something that I have to live with.”

Set up the right story, get the right access, get real people who are natural on camera – this always was a problem with having people ‘play themselves’ but much less so if they’re in their element, as opposed to a film set – and the product is almost intrinsically more powerful than fictional narrative, however well executed. And now we’re in a very odd position in which film, with its moguls and stars and glamour, is being shouldered aside by its weird step-sibling. Joe Exotic (currently serving a 22-year prison sentence) was Hollywood’s star of 2020, unless it was John Wilson. Three of The New York Times’ ten ‘best films’ of 2021 are documentaries.

Writing is a bit different. Writing is an inherently imaginative form. There isn’t the same heightened reality – the confessional shock – in seeing Joe Exotic sniffle when meth or arson are mentioned or seeing Robert Durst mutter under his breath, but writing has been consumed by the same reality mania. Memoirs are basically driving out fiction as a sellable commodity with autofiction as a sneaky compromise. Short stories have completely disappeared from their old perch in magazines. Online, there’s an endless appetite for articles, news, opinion, gossip – it’s very hard for anybody to slow down and read fiction. On the whole, fiction writers have responded by pushing towards speculative fiction – with fantasy breaking into ‘literary fiction’ via Pynchon, Marquez, Vonnegut, etc, with a writer like George Saunders canonized for a certain otherworldliness, and with a touchstone like Game of Thrones – the thing that connected all of us before Tiger King – a testament to what can only be achieved by the imagination.

But there is a very particular sweet spot that a critic like Shields has in mind, which is the borderland between reality and imagination. As a form, the novel has an inherent tendency to lower itself, to scoop up as much of reality as possible. Don Quixote, which invented and probably completed the genre, situated itself exactly in the space between the pretensions of the epic and the realities of modern life. The great advances in the novel always have to do with a certain collapse of artifice – with attention to nasty social realities in Defoe, Dickens, or Dostoevsky, with George Eliot’s understated move of “putting all the action inside,” as D.H. Lawrence phrased it, with Joyce’s pseudo-heroic structure of Ulysses’ journey covering all the multifaceted interior dramas of a perfectly ordinary Dublin day, or with a conscious deprettifying of language as in Hemingway, Céline, Henry Miller, etc. And the tendency is always there to break the contraption of ‘storytelling’ altogether – to insist on the reality of what’s being conveyed. Cervantes played an elaborate metatextual game to half-convince the reader that Quixote was a found document. Writers of the early modern period tended to load up their novels with fake affidavits of authenticity. Modernists attempted constantly to intercut their fiction with fragments of reality – Dos Passos’ press clippings, Melville’s whale factoids, although I’d be surprised if any reader of Moby Dick genuinely thinks the book is better for the chapter on ‘The Less Erroneous Pictures of Whales and the True Pictures of Whaling Scenes.’

In the 20th century a key break occurred from the other direction – journalists tired of restrictions on their reportage who suddenly started describing what they thought their subjects were thinking or inserted themselves in the story as a way to expand their narrative scope. I’m very surprised that that tendency – as seen in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Slouching Towards Bethlehem, In Cold Blood – has sort of died down, that journalists have allowed themselves to be reined in, just as I’m surprised that there wasn’t more follow-through on the experiments in fictional narrative form as devised by writers like Brautigan, Sarraute, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Roland Barthes. The simplest answer seems to be that, in the conservative ’80s and ’90s, the publishing industry kind of regained control over writing, domesticated the new journalism (which had always raised ethical red flags), discarded the nouveau roman, drove out the experimentalists, and crisply demarcated its genres, with ‘literary fiction’ always meaning realistic-but-imaginative and with ‘innovative’ fiction either meaning a push towards fantasy or stylistic pyrotechnics.

By around 2000, literary people were getting restless. “A genre is hardening,” wrote James Wood in a famous essay. “It is hysterical realism. The conventions of realism are not being abolished but, on the contrary, exhausted, and overworked.” Michel Houellebecq involved himself in an artistic movement centered on the magazine Les Inrockuptibles that, he said, had only one principle: “A little reality, man! Show us the real world, the things that are happening now, anchored in the real lives of people.” Dale Peck, in an equally famous essay, surmised that the “wrong turn in our culture” was embedded somewhere in Joyce and metastasized through postmodernism to literary-fiction-entirely-as-an-exercise-in-preening. “When I finished Black Veil [the book under review], I scrawled ‘Lies! Lies! Lies!’ on the cover and considered my job done,” Peck wrote.

And, as if on cue, a new taste emerged. Houellebecq probably led the way, with his connection to the French tradition of the feuilleton, the fictional work that was just a shade off polemic – with his characters like an elaboration of a thesis statement. Houellebecq’s interviews – which are always riveting to read, by the way – express a constant amazement at how simple good writing can be, how potent it is to just inject something real. “Looking back, I was surprised that you could get such an interesting character from just the one springboard of his sexual frustration,” he said of his first major protagonist Tisserand. “The success of Tisserand was a great education.”

Most interesting of all was W.G. Sebald, who seemed to fall from out of the clear blue sky. “Like discovering a missing sense,” was one of the typically ecstatic notices about Sebald. His books were unlikely hits – middleaged German men wandering around the English countryside thinking about Napoleon and Thomas Browne – but what seemed to work, what was crucial, was the sense of completely ignoring the conventional emotional grammar of the novel, of being grounded somewhere in the real world. “What he is most famous for is that his books are uncategorizable,” writes Caroline Angier in a new biography. “Are they fiction or non-fiction? Are they travel writing, essays, books of history or natural history, biography, autobiography, encyclopedias of arcane facts?”

By around 2010, there seemed to be a space opening up around the novel – a sense that the novel was no longer caked under by stylistic plumage and was accessible to other art forms. David Simon described The Wire as “a novel” – largely by analogy to Dreiser. Brian Reed, the creator of S-Town, called it “a novel.” Shields made the case vociferously for novelistic forms that were short, collaborative, that could take on many different guises but had to be anchored in the real world. “We all need to know how to begin telling a story for the cell phone,” he wrote in Reality Hunger. “One thing I know: it’s not the same as telling a story for a full-length DVD.”

But there’s something about all of this – I felt it strongly when I read Reality Hunger – of the subway preacher predicting imminent apocalypse and then the join letdown you all get when you pass each other the next day. For me, the works of art that really hit in the last decade were Mad Men, John, My Year of Rest and Relaxation, The Flamethrowers, Conversations With Friends, Cleanness, most of which were naturalistic, felt authentic, but fully participated in the conventions of fiction. So that’s the landscape we’re in – the new journalism and the nouveau roman abandoned, the old genres holding stubbornly in high art, but with a blurring of lines, most obviously in filmmaking, and a culture-wide shift towards work grounded in the real.

And then, recently, a breakthrough – Benjamin Labatut’s When We Cease To Understand The World, which was the book of the past year, for a while a kind of rumor, the book that the cool Europeans were passing around and then belatedly noticed in America. Labatut describes the book, which touches on the following subjects – chemist Fritz Haber, physicists Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrodinger, mathematicians Karl Schwarzschild, Alexander Grothendieck and Shinichi Mochizuki – as “a book made up by an essay, two stories that try not to be stories, a short novel, and a semi-biographical prose piece.” On its surface When We Cease To Understand The World reads like a bunch of Wikipedia articles artfully strung together – and I’m sure that, somewhere in the deep heart of the book, that’s where it originates, in the very familiar contemporary experience of surfing around, of going down online rabbitholes. In reading about various figures out on the frontier of knowledge, Labatut put together a thesis: that there was something in the nerve center of the universe that was so dark that anybody who came across the foundational truths (genius scientists most of them) went mad or gave up the search for knowledge or retreated into nihilism. This is all compelling and terrifying – and then you learn that several of the key passages, particularly related to Heisenberg’s epiphanies and to the transmission between Grothendieck and Mochizuki, are fiction, and at that point it’s hard even to know where to begin: the book turns out to be vertiginous nihilism as a kind of practical joke.

There’s lots to talk about in When We Cease To Understand The World, but I want to deal only with the form: essays that read like popular science that are contained by a single overarching thesis that are revealed, at heart, to be fiction. The book is Sebaldian in its annexation of the territory between fiction and history, but – to be honest – I never really got into Sebald, just found it fusty and ruminative, while Labatut is charged, sort of in the way that Shields is charged, intent on the big questions, both about the ontological shape of the universe and about the nature of writing. In terms of writing, Labatut’s discovery is similar to Shields’ – we just care more about people if we believe that they are real. In When We Cease To Understand The World, the people are real, they’re famous, their depictions by Labtut mostly match their biographies. But, cunningly, in a few key places, Labatut takes liberties that push the narrative in a certain pre-conceived direction. I’m not actually sure that Labatut really believes his own thesis – that the greatest scientific minds there are discovered an abyss in the ‘heart of hearts’ of existence, some mathematical black hole that all equations collapse into. I kind of think he was in a low mood and was entertaining an hypothesis while the real project of the book is the sly push towards fiction, towards making the reader understand that description and argument are inherently imaginative exercises, that any depiction of the world is at core imaginative. When We Cease To Understand The World concludes with Labatut finally showing his cards – a short story about a night gardener who had once been interested in mathematics but had given it up.

I have to say that I skimmed over the short story. I’m so conditioned to be interested in facts, in history, in celebrity that when I came across storytelling – the payoff that Labatut had so masterfully earned – I suddenly lost interest. (I had a similar reaction recently in reading the end of DeLillo’s The Names, a great book which also negates its own literary universe, which has a coda that’s meant to be a purer form of communication; and, as with When We Cease To Understand The World, I found myself glossing over that.) But Labatut, like DeLillo, seems to have anticipated that reaction. Labatut knows that the short story about the night gardener isn’t going to have the same impact as the salacious gossip, real and fabricated, about the sexual fantasies of Heisenberg or Schrodinger, and his truest point, I think, is that that’s the reader’s problem not his problem. Labatut isn’t the only writer who’s pushing into some intermediate zone of the non-fiction novel – Miranda Popkey’s Topics of Conversation, Miranda July’s work, particularly It Chooses You, Lauren Oyler’s Fake Accounts all seem to slide back and forth between the recognizably real and a self-consciously fictional domain – but Labatut once again breaks ground in adjudicating between the forms. Our obsession with celebrity, with fact, with the pretense of reality, is a delusion, he seems to be saying, a mania. Reality has its undeniable appeal – as Shields notes, we all get a charge when we’re told that something is a ‘true story,’ that ‘something really happened’; we get tired and restless as soon as we sense the mechanisms of storytelling – but, actually, that’s a sort of deficiency in the culture, and ‘reality,’ as any halfway decent philosopher will tell you, is a deeply subjective construct. Fiction and reality can seamlessly blur together, as Labatut nicely demonstrates, and, between the two, imagination truly comes up trumps.

writing to capture reality is like fucking to capture virginity

Wonderful thoughtful piece! One quibble though I may be misunderstanding what kind of documentary you are referring to. People were making profitable docs at least since 1990s. Trials of Life was a massively successful Time Life series, Real World launched around then, Paris is Burning, etc.