Dear Friends,

This is — I am highly confident —the best week, publishing-wise, I have ever had. I have a piece in Compact Magazine on Robert Kaplan, a piece in UnHerd on psychedelics, an interview on writing style in Sean McNulty’s wonderful Auraist, and then very, very excitingly,

, , and I have launched The Metropolitan Review.Our manifesto is here. The Review is a books and culture magazine, in the vein of the original New York Review of Books or Village Voice Literary Supplement. We are dedicated to ambitious, unapologetically high-brow essays and book reviews, and, most vitally, we are ‘writer-first.’ We have a vision but are imposing no style. We are looking to create a venue for writers to write entirely as themselves — and to be as free, pugnacious, and bizarro as they like. Please consider subscribing, donating, and pitching us (or any combination of those three)!

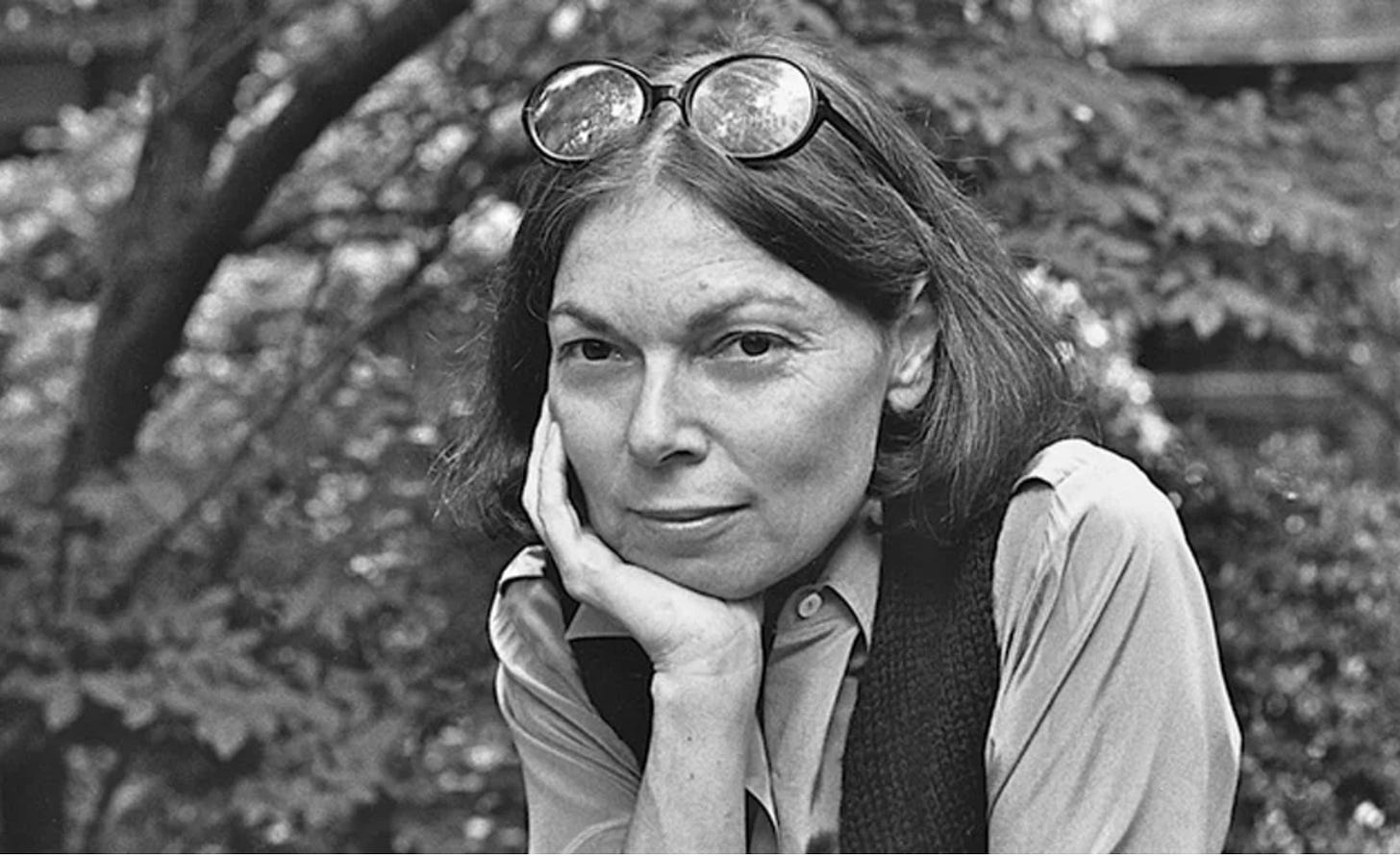

Today, I’m sharing a discussion — an outgrowth of a Media Studies course I’m teaching — on Janet Malcolm’s The Journalist and the Murderer.

Very best,

Sam

JANET MALCOLM’S THE JOURNALIST AND THE MURDERER

The Journalist and the Murderer is one of these books that it’s almost impossible to imagine anybody who’s not a professional journalist finding interesting but is a kind of badge of admission for the journalism community.

The book, with its confusing over-abundance of Scots/Irish names, is built around a civil litigation case between Jeffrey MacDonald and Joe McGinniss. MacDonald, an army doctor who stood accused of the murder of his wife and children, enlisted McGinniss to write an account of his trial. The two became friendly during that period, exchanging correspondence and leaving MacDonald with the impression that McGinniss would help to rehabilitate his reputation. Instead, McGinniss over the course of the trial became increasingly convinced of MacDonald’s guilt and the book he wrote was a hit job — painting MacDonald not only as a killer but as a pathological narcissist. MacDonald contended that McGiniss had breached the terms of their contract — the “integrity of his life story was not maintained” and, from prison, filed suit. The civil trial resulted in a hung jury, but the jury was clearly sympathetic to MacDonald — “five of the six jurors were persuaded that a man who was serving three consecutive life sentences for the murder of his wife and two small children was deserving of more sympathy than the writer who had deceived him,” Malcolm writes — and the parties settled, with McGinniss paying MacDonald $325,000.

In the end, the complicated story of the MacDonald murder is wholly incidental to Malcolm’s account — her book reads like an appendix to a much longer work. McGinniss, as well as the jury in the criminal case, were persuaded that MacDonald had done it. Malcolm all but assumes that MacDonald did it, although — like the jury in the civil case — that hardly prevents her from being far more sympathetic to him than she is to McGinniss, whom everybody, collectively, loathes. She keeps describing MacDonald’s feral, athletic energy — how gracefully he looked even while submitting to the humiliating procedures for being handcuffed in the visitors’ room of his prison. It turns out, actually, that there may have been more to MacDonald’s case than was realized at the time — Errol Morris has a doorstop of a book, A Wilderness of Error, that follows the tangled story of police mis-investigation in the immediate aftermath of the murders and of Helena Stoeckley, who at different times confessed to being part of a group that killed MacDonald’s family exactly in the way that MacDonald describes it.

All of that is off-screen. What matters here is the fraught, and deeply unequal relationship between McGinniss and MacDonald, which is to say between any journalist and their subject, and Malcolm uses that to indict journalism as a whole. “Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible,” she famously writes in her opening and she concludes, “Almost from the start [of my career], I was struck by the unhealthiness of the journalist-subject relationship, and every piece I wrote only deepened my consciousness of the canker that lies at the heart of the rose of journalism.”

This kind of ritualized betrayal takes on an almost spiritual dimension. As Malcolm writes of MacDonald’s accusation against McGinniss, “McGinniss was guilty of a kind of soul murder.” The soul murder, Malcolm claims, is actually the whole point of journalism. A journalist, in society, functions like a priest or therapist — they have the capacity to reach the deepest layers of the soul, to extract the confession — with the difference that the journalist is not paid by the client but by a gawking, rubbernecking public that delights in the betrayal of the subject. That entire dynamic would seem to be readily resistible — the subject could simply refuse the journalist’s ministrations — but for curious psychological reasons that is impossible. “Something seems to happen to people when they meet a journalist, and what happens is exactly the opposite of what one would expect,” Malcolm writes. “One would think that extreme wariness and caution would be the order of the day, but in fact childish trust and impetuosity are far more common.”

Everything here would seem to point to an indictment of predatory, confidence man-type journalists, who were especially prevalent in McGinniss’s era, with the New Journalism breaking down some of the traditional compartments and ethical standards in the profession, but Malcolm wants to go further — she wants to pin the blame on the structure of the interaction rather than the behavior of individual journalists, and here, she goes on to say, the betrayed subject is far from an innocent victim. “What gives journalism its authenticity and vitality is the tension between the subject’s blind self-absorption and the journalist’s skepticism,” she writes.

Journalism, then, comes to be understood as a soap opera of violation combined with the secret desire to be violated. As in a Kafka novel, the subject is interested in the journalist because the subject is guilty, knows themselves to be guilty, and is interested in the complex process of confession and absolution. The absolution occurs through the act of betrayal — the journalist lifting the story into the public sphere and, through their manipulation, in some way taking on the sins of the subject. In the case of MacDonald and McGinniss, the civil jury seemed to have almost no residual anger at MacDonald — he had already been punished was the view — and the full force of its loathing was shifted onto the new scapegoat, McGinniss. This process can be understood as comparable to the transference, in which the healing is not meant to occur in the flow of information from patient to therapist but in the sort of pagan rite where the therapist is pulled into the patient’s psychological drama and acts out a play of the patient’s projections. Here, though, the drama doesn’t occur in the sanctum of the therapist’s office but in public, with the public-at-large enjoying every moment of the betrayal dynamics.

The question is if all journalism is like this and participates in these dynamics. Morris, who viewed The Journalist and the Murderer as a postmodern shortcut through a highly-complex subject, said, “Malcolm wrote about Joe McGinniss as if he were representative of journalism per se, and I respectfully disagree. There was something very pathological in the relationship between McGinniss and his subject.” Malcolm conceded that the MacDonald/McGinniss case is “a grotesquely magnified version of the normal journalistic encounter.” And a great deal of what Malcolm is addressing refers to the long-form confessional style that was briefly in vogue through the New Journalism but doesn’t have all that much to do with nuts-and-bolts, public service-style reporting. For Malcolm, something like reality TV, with its carefully orchestrated melodrama of producers manipulating subjects and subjects happily submitting to their manipulation, would be very close actually to the real heart of journalism — which is clearly a departure from what journalism means for most people. But, on the whole, I think, Malcolm is basically right. As Douglas McCollam puts it, what seemed like a fringe, trollish argument at the time she wrote The Journalist and the Murderer has come to be something like conventional wisdom. Journalism is exploitative at its core, there always is a power imbalance between journalist and subject in which the journalist holds the subject’s reputation (the ‘integrity of their life story’) in their hands, but, even more than that, it is this dynamic of manipulation and betrayal that gives journalism its charge, that moves the discipline from the accumulation of facts and the dispensing of public service into something that’s more resonant and arresting, that taps deep into the collective psyche, even if it is also deeply perverse.

Janet Malcolm was a goddess and Journalist and the Murderer is an extraordinary book. Thumbs up for giving it and her a shout-out.

Sam,

Nice. Interesting. Two points of clarification. "Journalism" here is overinclusive. A story about the broken German business model, or for that matter much of what you do (read, synthesize, comment) does not involved the personal interrelationships described here. You are really talking about the relationship between interviewer and interviewee, sort of on the model of therapy. Second, and as a few folks have suggested already, I'm not sure the power imbalance is constant, which the piece seems to imply. Speaking as a writer, I'd love to be "exploited" if I could sell books! Anyway, I liked this outing.