The answer is, of course not. The Times is indispensable, now maybe more than ever. When print journalism largely collapsed during the recession, The Times became the last one standing and, increasingly, something like the entire print journalism industry. The Sunday Times runs about 500 pages. Somewhere around 7% of all newspaper reporters in the US are employed by The New York Times — which is a staggering number. The Times maintains an impeccably fact-checked style of reporting — from a Journalism 101 perspective it’s always very difficult to fault any of The Times’ pieces. All over the world, it has retained an ability to access those in power — meaning that, for all kinds of important political stories, The Times is often the sole journalistic source. It has sweeping international coverage while almost everybody else has had to cut back. It cranks out a significant number of groundbreaking investigative pieces. And it does all of that with a signature elegance and gravitas.

But, at this point in its existence, I would say that The New York Times does about as much harm as good — some of it through no fault of its own.

Let’s try to enumerate everything that’s bad about The Times.

First of all, The Times has become nearly a monopoly of established respectable opinion. The Times itself is not to blame for winning against its print competitors, but a monopoly always deeply distorts a market. In certain national security-type stories, The Times, with no particular risk of getting scooped by anyone else, finds itself protecting its relationships with its sources and simply doing what it’s told by them. It’s the exact same cozy relationship that The Times had with the national security establishment before the journalistic disruptions of the ‘60s and ‘70s.

Meanwhile, its monopoly of respectable opinion means that Times writers know that almost anything they say will be accepted as gospel truth by a large percentage of readers and so the conversation within The Times becomes not about trying to report the news accurately but about trying to use its reportage to persuade the readership of what Times reporters believe it is important to say. It is still well worth reading the transcript from a New York Times town hall in 2019 in which younger reporters take older reporters and editors to task for being insufficiently progressive in their coverage. A conversation like this is only possible in a bubble, with a newspaper speaking to a captive audience, in which the paper is basically free to spin as it likes, expecting little pushback from competitors.

The Times has allowed a certain amount of woke “capture” to take place. For ferocious critics of The Times, like

, reading The Times now is the “new Kremlinology.” You have to dig past the spin that The Times puts on the story to get to what the underlying reporting says. This is particularly egregious with science stories and culture war stories. As a fairly mild example, I found myself exorcised recently by an article called “How Psychedelic Research Got High On Its Own Supply,” which seemed to put the nail in the coffin of the entire ‘psychedelic renaissance,’ concluding of a high-stakes MDMA trial: “Rejection….was the capstone to months of increasingly loud concerns being voiced over the quality of Lykos’s clinical trials.” But you would have to comprehend a glancing reference at the end of the second paragraph and then read all the way until the tenth paragraph (!) of the accompanying reported piece to realize that the trial had failed because of a sexual relationship between a therapist and patient after the dosing session had concluded and not at all because of any issues with the MDMA itself. There were far more severe examples of this kind of selective reporting during the pandemic.Meanwhile, the liberal slant of the op-ed pages has dramatically exacerbated itself, and The Times has given space to a number of progressives saying totally crazy things — “The Constitution Is Sacred. Is It Also Dangerous?” ran a typically eye-popping recent headline — without anything like an equal-and-opposite conservative counterweight. I am actually less critical of The Times on this score than somebody like Taibbi is, though. I think The Times has largely gotten it back together after the height of woke madness.

The Times’ financial structure is inherently unstable. This, actually, is the point of Bari Weiss’ critique of The Times. As she said in a 2021 interview with Jordan Peterson, the advertising business has largely collapsed, making The Times disproportionately dependent on subscribers — and on not alienating subscribers. “So you better believe that in order to keep your subscribers, your readers, the people paying the bills happy, you have to give them what they want,” Weiss said. “And now The Times has become something more like MSNBC in print…heroin for our side.”

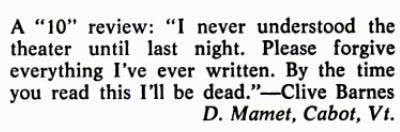

The Times has no real business sitting in judgment over books, plays, or films. The New York Times Book Review has been a disaster from the beginning, and similar critiques could be made of the entire arts section. The first problem is a mismatch between what newspapers do and what book critics are supposed to do. Newspapers are supposed to cover what’s newsworthy — and to translate that for busy professional types. But art is an activity of a completely different sort, and the result of this marriage of inconvenience is the newspaper review, which is almost always a plot summary and then a snarky judgment. The second problem, which is specific to The Times, is that The Times has so much authority that it can make or break entire careers based on the judgment of their reviewers — or, just as often, in the choice of what they do or do not review. Michiko Kakutani was, for decades, by far and away the most powerful figure in American literature in spite of having never written a novel herself and being widely disdained by high-end working novelists. (Kakutani was far from the only Times reviewer to generate that reaction. See below.)

The disappearance of arts sections from newspapers around the world is a good thing, actually — it ends the mismatch and helps to restore critique to artistic circles. But even as that has happened, The Times’ arts section has only metastasized and exerted more of an outsize influence over the literary and art worlds. What that translates to is an intensely dull and unimaginative arts scene, with artists maintaining their position in an invisible but intractable hierarchy. The make-it-or-break-it crux of virtually any American work of art is whether it gets a review in The New York Times and whether that review is generally favorable. Artists know that, and a tremendous amount of energy goes into ensuring that their work aligns with The NYT’s sensibilities. The Times knows it as well and is duly polite and deferential to the publishers, theaters, etc, that have gone to so much trouble to give The Times what it wants while just politely ignoring anything that falls outside of that ambit.

The Times’ house style kills distinctive voices across the writing world. The Times, of course, is not just an institution. The Times is the major leagues of journalistic talent. Virtually anyone who can get a job or freelance opportunity at The Times takes it. Anyone one arrives at The Times regards it as the pinnacle of their careers. But if you write for The Times, you can’t really write. Everything has to get ironed out into the house style — which often means getting almost entirely rewritten by the inner rung of Times editors. The result is that anybody who writes for The Times inevitably ends up sounding not at all like themselves. “I have read reviews there by some of the wittiest writers whose prose sparkles elsewhere but who, when transplanted to the hallowed and hollow grounds of the Times, quietly shrivel and hush,” writes Yasmin Nair in a cutting piece for Current Affairs. This is most noticeable in the Book Review but also with the op-ed columnists. Anytime an interesting writer gets a Times column, it’s like their personality gets sanded away for it. And that smoothing-out has knock-on effects. All throughout the journalistic world, writers are trying to break into The Times one day, which means learning to write like The Times. That’s generally ok, but The Times is a 150-years-old publication, and adapting one’s style to it means also cutting off what’s fun and free and contemporary in one’s own writing style. Together with the AP, The Times probably, for instance, bears the leading responsibility for why college newspapers are always so unreadable.

The Times has become an entertainment center as much as a newspaper, the Tesla of journalism. I certainly understand the logic of this from a business perspective — the more recipes and crossword puzzles The Times has, the more it hooks its consumers. But this metamorphosis — from the dreary ‘paper of record’ to the fun-loving arcade — doesn’t come without a cost. The cost, as I can see it, is somewhat subtle. It’s that The New York Times finds itself with an obligation to create a lifestyle vision. The lifestyle is bourgeois to its core and is built around the kinds of people who are understood to be The Times’ readership base — people who have the sort of knowledge to enjoyably do The Times’ crossword, who have the leisure to cook the complicated recipes, who are interested in the travel destinations and weekend getaways, who are having anxious monologues with themselves about cell phones in schools or co-workers who might be having a second job on the sly — the kinds of crises that pepper ‘The Ethicist’ — and whose greatest dream is for their kids’ wedding to be featured in ‘Vows’ or maybe even one day to have a Times obituary of their own. These lifestyle tips creep out of the entertainment sections where they are carefully siloed and show up in the op-eds and in jaunty, clickbaity front page pieces. “Making Tender Scones At Home” and “Wok Hei Is Vanishing From Hong Kong, My Mom Wanted To Taste It Again” have a way of creeping up higher than they should on the front page. The old left-wing critique of The Times — which did much to spawn The Village Voice and the alt weekly scene — was that The Times was hopelessly bourgeois and indifferent to the real concerns of working-class people. Now, with the left-wing industrial proletariat receded into distant memory, The Times’ bourgeois taste opens it up to a similar critique from the MAGA-ish right — that The Times simply doesn’t get it, that the upbeat lifestyle sensibility blinds it to the reality of so many Americans who are living paycheck to paycheck or else in terminal despair.

I find it very, very hard to resist Star Wars analogies when thinking about The New York Times — The Times as this Death Star prowling around the galaxy, looking for any remaining subject matter to hoover in with its tractor beam, with its own ironclad position as the voice of the establishment, with its editorial mandates orchestrated by a little-known-to-the-public editorial board. In a panel at the Novitate conference, Walter Kirn talks about the current media ecosphere dividing up between the Empire (what Curtis Yarvin would call the Cathedral) and the ‘rebel alliance,’ these malcontents strung out across the blogs and podcasts. For the first time with Substack, the rebel alliance has something like an organizing structure. That’s not to say that the rebel alliance is better — it is full of all kinds of oddball figures, the sorts of people who Han Solo might be friends with — but, then again, one school of thought would hold that the fourth estate should be oppositional, fractious and inchoate. What’s become clearer is that the rebel alliance has a leading adversary, that The Times has become — more so than ever — the voice of the establishment; and, whatever you think about The Times itself (personally, I can think of lots of good things to say about The Times), it can never be in the interests of the public sphere to have it to be so completely dominated by a single entity.

Delightful to read, as expected, and I agree with most of what you say, as far as it goes. That said, I think you are too forgiving of the NYT (which I have read daily, for years). The elephant in the room is politics in a constitutional way, that is, is this the 4th estate in the sense that the US has relied upon since Ben Franklin ran a paper? With a monopolist serving ""heroin for our side" (as you nicely put it), then public discourse as represented by print media is not coterminous with the polity, which gets its "facts" elsewhere. Nor is the NYT nearly as scrupulous as your opening suggests, or is only about the small things. Instead, disadvantageous news is simply elided, which a monopolist can do. Anti-Israel protests in front of Sloan Kettering's cancer ward? Only after WSJ and others reported, and buried. With its near monopoly, the NYT can report (and some of its staff openly espouse reporting) only those stories it believes advances the cause, or trimming/cutting/emphasizing in order to do so. You note this. So, simply didn't report in any serious way on Biden's collapse. Harris has free pass as Barri Weiss & Co and Ross Barkan keep saying. The news will be curated. This is not the bias inevitable to being human; this is a shift in professional ethos.

At one level, we might say that the shift is from reporting to advocacy. But I think it's actually a bit deeper. As you note, "Tesla" (again, nice,) the Times has become about "lifestyle." It's more than just entertainment. It's sex and parenting and what to eat and where to travel and what to read and . . . there is something quite totalizing about this. The Times is the organ of the symbol manipulating class (I'm a law professor), that is, it articulates, reiterates, and solidifies a class identity. This is where the comparison to Pravda has bite. To think that my class is conterminous with the nation, or simply has the legitimacy to rule the nation, is a Clintonite fantasy. We've lost what another group of mandarins called the mandate of heaven, and the decline of the NYT is a big piece of that puzzle.

I see two futures, in principle, for the NYT, and one likely outcome. The Times could attempt to "go back" and become the Gray Lady, the paper of record, if perhaps with some loyalty to the Dems. But reputation is hard to recover, and it would require a wholesale turn around, probably a shift in ownership and a bloodbath. Alternatively, the NYT could really lean into this lifestyle stuff. The magazine for the class of people who love the Ivy League. (Yes, of course, and my kids too.) My guess is that nothing of either sort will happen anytime soon. Instead, the NYT will continue pretty much as it is: claiming political virtues it does not have, and articulating received opinions on just about everything, in that signature good but deadening style that you decry. The paper has never been more profitable, and if it ain't broke, why fix it?

The bit on lifestyle is really insightful, Sam. I'd thought about that with the games/arcade silliness (which I participate in, shamefacedly), but not with how this creeps into other areas.

One byproduct of this monopoly is that fact checking is no longer a given. Maybe there's some of that for the most prominent pieces, but there is a lot of minor material that is not fact checked at all, except by the author, which of course is not sufficient.

This is the biggest problem with Substack, too, as far as I can tell. Ted Gioia recently posted something about how many individual Substacks you can subscribe to for the cost of a single newspaper subscription, which I confess made me both sad and angry. Sure, you get more unfiltered voices, but the platform defaults to the hot takes, to Hamish and Chris and Mills riffing on live video. That might seem hip and everything, but it is not remotely comparable to journalism. Who fact checks Ted Gioia or anyone else publishing on this platform? Maybe that world is gone for good, and we're now stuck with a sea of competing facts. But I'd like to see some evidence of Substack voices that are actually doing righteous watchdog reporting and building real credibility. There's plenty of gimmicky content here, too, and the grievance hustling and the advocacy.