Dear Friends,

I’m sharing a piece related to a new philosophically-themed novel I’ve finished. This is a habit I’m developing — to offload some of the research I’ve done for the novel in the form of a post; and to whet your appetite if I can ever figure out the right outlet for long-form work.

I have a piece out at UnHerd analyzing Trump from a media studies perspective and trying to understand why the Democrats have been so slow to adapt.

Best,

Sam

SARAH BAKEWELL’S AT THE EXISTENTIALIST CAFE

My mother had a shelf of 20th century philosophy books and, of everything in my parents’ library growing up, these books were the most perplexing to me. The earlier philosophers were at least sortable into distinct movements — Idealists, empiricists, and so on — but for the 20th century philosophers I couldn’t figure out an access point. They seemed all to be in the middle of a conversation with each other.

When I discovered Sarah Bakewell a couple of years ago, it was the immensely satisfying experience of finding a key that fits into a long-neglected look. Bakewell — an astonishingly clear writer and lucid popularizer — managed to draw up coherent schema of this whole fractious, complicated world, and to do so by putting the philosophers simultaneously in social and intellectual relationship to each other.

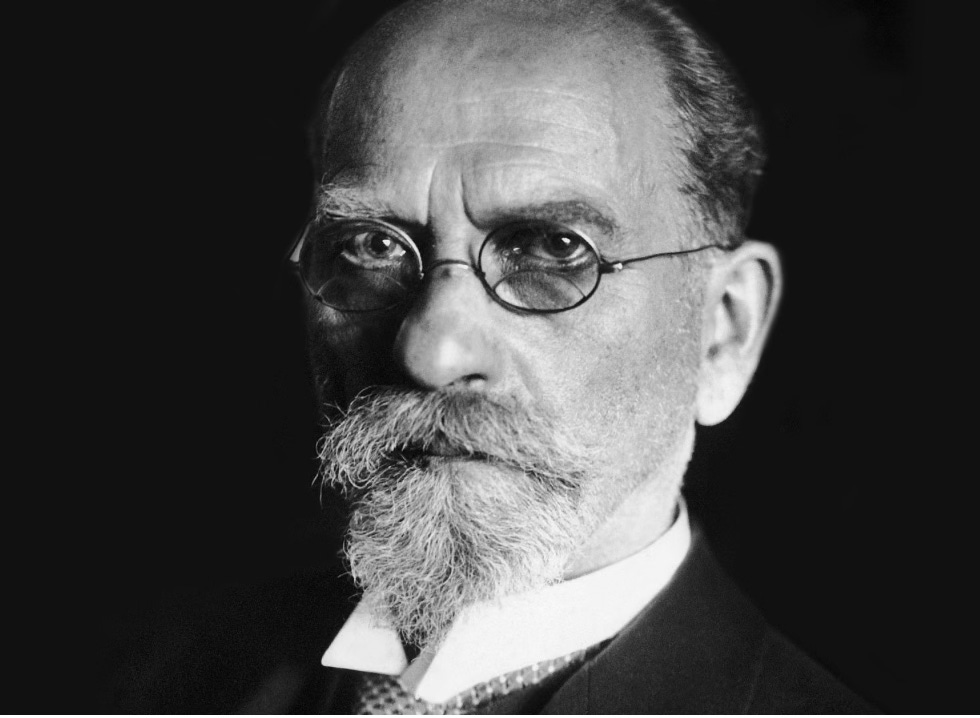

For Bakewell, the key to all of this is phenomenology — which goes a long way towards explaining why it’s so difficult to find any kind of access point. The phenomenologists are all but unreadable, they seemed to relish making things difficult. But at the same time the phenomenologists — led by Edmund Husserl — found an intellectual technique that seemed to ever-proliferate. Everything became available to philosophy. The trick was the époché — i.e. bracketing — which made every object, every moment, its own domain of philosophic inquiry. If the circle around Husserl tended towards obscurity, the technique opened up startling possibilities for other intellectuals. Proust and Nicholson Baker are, fundamentally, phenomenological writers. More immediately, word of Husserl’s techniques reached Paris at the turn of the 1930s where Jean-Paul Sartre, then a frustrated teacher, seemed to be losing interest in philosophy. Bakewell writes of the key conversation between Sartre and his John the Baptist, Raymond Aron. “You see mon petit camarade,” Aron said, pointing to the apricot cocktail between them, “if you are a phenomenologist you can talk about this cocktail and make philosophy out of it.”

The effect of all of this was electric. “Thinking has come to life again,” crowed Hannah Arendt in reference to Heidegger’s parallel inspiration. Sartre, for his part, blanched at what Aron said, and then, as soon as he was out of sight, raced to the nearest bookstore, asked for everything they had on phenomenology — which turned out to be Emmanuel Levinas’ extraordinarily dense The Theory of Intuition in Husserl’s Phenomenology, which Sartre, not waiting for a paperknife, tore open with his heads and read walking down the street. That excitement, just by itself, speaks volumes. There really is a startling contrast between the anemic philosophy of the early part of the 20th century (John Dewey and so on) and the philosophy of its middle section, which became as cool as literature or jazz music.

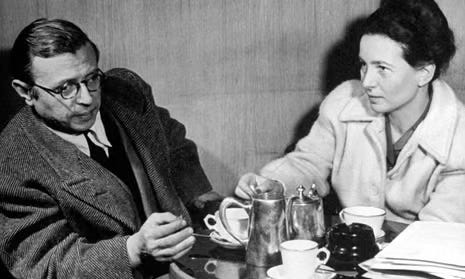

I’ve read very little of Sartre and he seems to exist as a curious sort of ellipsis in our high culture. We know that Sartre was important, but we can’t reconstruct why, and he has largely been moved off into the Gallic sub-section of the history of ideas — there’s an assumption that French people probably understand Sartre but that he’s likely one of these overly elegant Frenchmen whose ideas always seem to fold back on themselves.

But that turns out not to be right, and Sartre, actually, does have a Big Idea. It’s that choice is the fundamental activity. “Existence precedes essence,” he put it, meaning that we are defined by the decisions we make more so than who we are, i.e. by any sort of identity. It follows from there that — as if in the polar opposite of determinism — we are making decisions, choosing our being, every moment of our existence. And it follows from there as well that, even if so many of our choices have precious little impact on the world around us, that that doesn’t make any of them less real. Our inner lives, and our constant choices, have as much power to them as anything in the ostensibly material reality. “To wrest oneself from moist, gastric intimacy and fly out there to what is not oneself” was how Sartre — euphorically if a bit disgustingly — wrote of the goals of existentialism.

And that emphasis on interiority, as well as creativity, produces a certain pathos with it. As Simone de Beauvoir put it towards the end of her life:

I think with sadness of all the books I’ve read, all the places I’ve seen, all the knowledge I’ve amassed, and that will be no more. All the music, all the culture, so many places; and suddenly nothing. They made no honey, those things, they can provide no one with any real nourishment.

The explanation for why Sartre has faded in importance is, largely, that he was so undisciplined. Everything came together for him, and the existentialists, in the year of years, 1945. As Dada and Expressionism spoke to Europe after World War I, existentialism spoke in particular to France’s experience of World War II — these endless, almost incalculable inner choices that people made on the axes of survival, collaboration, and resistance that seemed, whether they made any difference or not, to speak to essential character. No philosopher before or since has had his acclaim or centrality to the culture — Boris Vian, who had a way of getting to the heart of things, depicted Sartre arriving at a lecture on an elephant.

But then Sartre seemed to unravel in a frenzy of overwriting and overthinking. As Bakewell describes his work habits in the 1950s:

Sartre’s fear of underproducing often drove him over the edge. “There’s no time!” he would cry. One by one, he gave up his greatest pleasures: the cinema, theatre, novels. He wanted only to write, write, write. This was when he convinced himself that literary quality control was bourgeois self- indulgence; only the cause mattered, and it was a sin to revise or even to reread.

This frenzy went in unfortunate directions. As Bakewell writes, “He was led to believe that he must reconcile his existentialism with Marxism. That was an impossible and destructive task: the two just were incompatible.”

Bakewell had started her book expecting to despise Sartre — he has come down to us as a pompous apologist for Stalinism and his abundant affairs with Beauvoir’s knowledge and assistance are now being recast as grooming and procurement — but she found herself, she writes, being surprisingly drawn to him, and I had something of the same experience. He wasn’t a charlatan or hack. He really was a seeker and he really loved to write — cranking out something like 20 pages a day and endlessly submitting prefaces, etc, almost always for no pay. Most of all, he seems like somebody who really needed Substack, who always got bogged down in these 1000-page-long manuscripts and would have been better suited just with a steady output of material.

“He is good,” Merleau-Ponty said in his assessment of Sartre, and this simple verdict, surprising for a figure like Sartre, is Bakewell’s verdict as well. His fame notwithstanding, Sartre lived all his life with his mother. He was France’s most famous intellectual but he was chronically short of money — his habits of leaving immensely large tips and splurging on wine caught up with him — and he had to pick up endless random writing commissions to make ends meet. What comes through, above all, with Sartre and his crew is that they had no institutional affiliation. They really were an alternative culture and, in a sense, created the whole idea of counterculture. They were interested in truth and creativity — those really were the highest ideals. Far more than their own fortunes, they were invested in discovering what it truly meant to be free.

Bakewell's book on Montaigne is a delight.

I read this book a couple of years ago. It's a good example of how to popularize a complicated subject without dumbing it down. It stands with other useful intros to existentialism, such as those classics of the 1950s, William Barrett's "Irrational Man" and Colin Wilson's "The Outsider" (which is more a work of lit-crit than anything else).