I was surprised by the paroxysm of grief that swept across the media this week with the death of Richard Lewis — it’s hard to think of somebody who was quite so beloved without ever exactly being an icon in their own right (and who was, essentially, in the shadow of someone else i.e. of Larry David).

The sensation (and this is one of the best things about culture) is of having some experience that you think is somehow specific to you — e.g. finding yourself for some reason really excited every time Lewis shows up on Curb — and then realizing that everybody else feels exactly the same way.

Lewis wasn’t exactly a core member of the Curb universe — he’s not Larry, Cheryl, Jeff or Suzie. And he was the one who seemed least to get with the program — he broke more than any of the others (you’ll notice, by the way, in how many of Lewis’ best scenes, the camera has to be on Larry) and he tended to forget that he was supposed to be the straight man and to instead try to one-up Larry. But there was something just so agreeably bizarre about him — the black clothes, the string of ill-starred relationships, the bottomlessness of his anxiety — and he represented (I’ll say more about this) something vital in Curb’s structure.

Curb, let’s face it, hasn’t been itself for awhile. The falling-off began somewhere in the thick of the #MeToo movement, when the episodes suddenly started getting a bit more defensive and explicitly tackling cancel culture questions. Then it veered into self-parody — Larry being too much, too many people commenting on Larry being too much. Then everybody got old. Marty Funkhouser died (or “went to China,” in the show’s euphemism). Shelley Berman died. Richard Lewis died. And that — more than the limp to the finish line with Irma Kostroski or Maria Sofia or whoever is on the show now — is the real finale.

So, if we’re trying to write an obituary for Curb, let’s try to figure out a little bit of why it’s as funny as it is. There’s the sort of obvious armature of comedy — which is Larry pushing far, far past the point of shamelessness; and Larry inhabiting a pleasant curmudgeonly amorality (the “no hugging no learning” dictum that is supposed to have made Seinfeld the breakthrough that it was). But lots of other comedians do that. A great deal of it is that the amorality and the curmudgeonliness broke through layers of sentimentality that almost everybody has when they express themselves in public and got down to a kind of bedrock of how people actually live — which is in a state of vague, constant annoyance. A tremendous amount of Curb and of Seinfeld (the “show about nothing” principle) is that it deals with all the ambient irritations of contemporary life that most people pass over but that everybody recognizes, and in so doing it seems to colonize much of daily life. It’s very difficult to have a “stop ’n’ chat” or a “sneeze ’n’ shake” or to consider whether it’s possible to bribe a maître d’ as opposed to bribing a pharmacist or to look at a phone in the doctor’s office or to hear that somebody needs a kidney transplant without thinking about the relevant episode in Curb. Nicholson Baker, by the way, does the same thing in literature, but Seinfeld and Curb have broken under the skin of the culture in a way that nothing else, really, has. A friend of mine once overheard two business people, bumping into each other on a train, run out of topics on their own lives and then spend the entirety of a long train ride happily swapping Seinfeld bits. In the Sheila Callaghan play Elevada, a woman with a terminal illness, thinking through what she’s missed out on in life, discovers that she’s never really watched Seinfeld — and then spends her last remaining months binge-watching episodes and quoting them to everyone she meets. At times I’ve found it very difficult to meditate because I get Curb episodes running through my head. And god knows how many lonely people in hotel rooms, or skimming around late night TV, have found themselves watching the three or four channels that seem to have become entirely Seinfeld channels and finding that Seinfeld (and Curb) are somehow the only thing that really gets daily life.

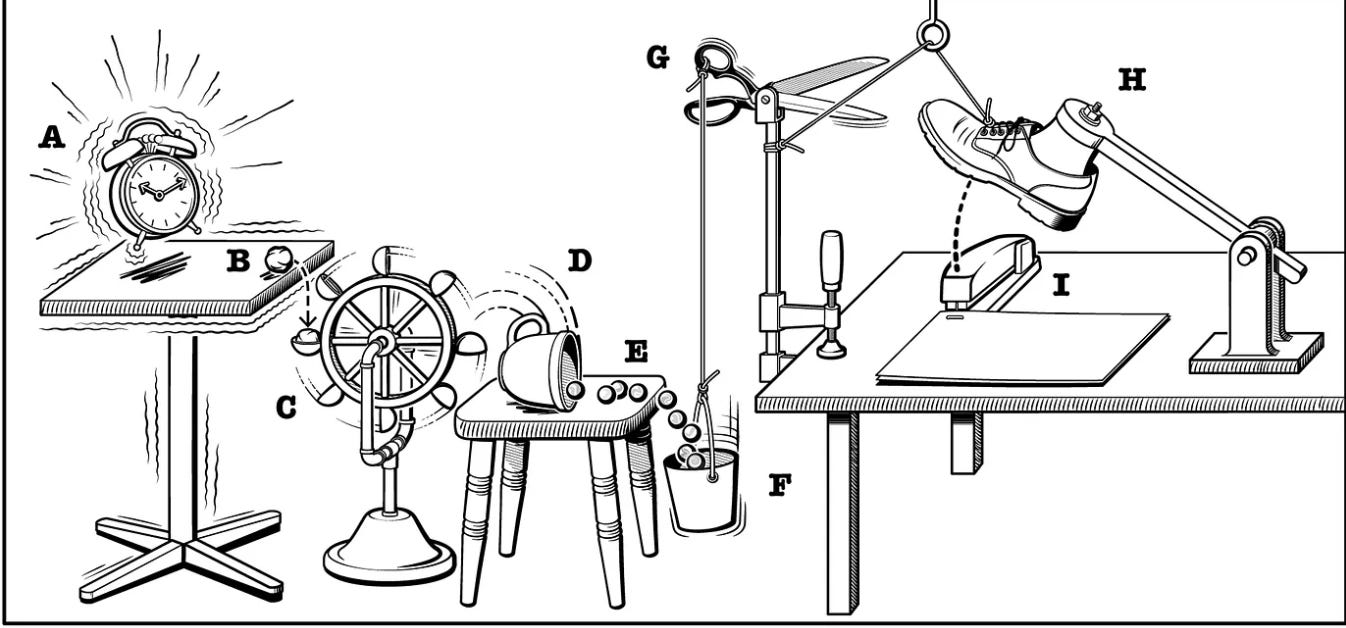

The main point of Curb is how well observed it is. The next point is that it’s so well structured. As some old acquaintance of Larry David’s put it, “If it was up to him he would just set everything in a Chinese restaurant, but then he got into plotting and of course now he’s the master of it.” I’m absolutely convinced that the real secret of Curb isn’t Larry’s orneriness or the banter or maybe even the hyper-neurotic perceptiveness; it’s mathematics. My sophisticated analysis of this is that each Curb episode has three major threads (one usually connected to the season arc) and one motif. The motif is usually something small and is often the punch line at the end of the episode. The three threads cross-cross, bringing Larry to the brink of some social catastrophe, and then painlessly resolve themselves (ideally with something from one thread neutralizing the problem of one or both of the other threads).

So, pretending we’re Northrop Frye or something, here’s the breakdown of a couple of episodes. In ‘The Surrogate,’ a sort of workhouse episode from Season Four, the overarching thread (connected to the season as a whole) is that Larry must pass a physical in order to continue performing for The Producers. He’s in perfect health (other than a separate scrotal injury), but he keeps failing the physical in large part because he comes to appreciate the value of having heart-monitoring electrodes strapped to his chest: anytime somebody tries to punch him (that happens twice in this episode) he can pull up his shirt and pretend he’s having a heart attack. That turns out to be an effective, if cowardly, gambit, but unfortunately sets him back to square one for the physical since he keeps being delivered to the hospital after the fake heart attacks and can’t convince the doctors that he’s faking it. The second thread is the puzzle of whether or not to get a present for a surrogate mother at a baby shower, and this leads to an escalating series of crises, with Larry getting a present for the surrogate (which offends everybody else) and then inadvertently convincing the surrogate to keep the baby, which then prompts the intended father to threaten to beat him up, which Larry hears about as he’s on the treadmill for his physical, which causes him to once again fail the physical. The third thread is Lewis dating a black woman and being nervous about his penis size compared to the black men she might previously have dated, which leads to Larry interrogating the different black women he comes across about their past boyfriends’ penis size and which leads to Larry trying to sneak a peak at Muggsy Bogues’ penis when Muggsy is peeing in the urinal next to him, which leads to Muggsy trying to throw a punch at Larry and then Larry faking a heart attack and being admitted to the hospital and once again failing his physical. Then the motif is about getting interrupted while leaving voicemails. Larry tries to call David Schwimmer’s father to apologize for something that happened in an earlier episode but is rear-ended as he’s making the call and curses out the guy who hit him, forgetting about Schwimmer’s father. This is dropped. The various threads all resolve themselves: Larry finally can take off the heart holter, the surrogate has changed her mind and agreed to give up the baby, black men’s larger penis size turns out to be a myth, much to Richard’s relief. But then the motif returns with Larry letting a call go to voicemail and David Schwimmer’s dad cursing him out.

In this one, the threads interact but resolve themselves on their own. In ‘Wandering Bear,’ from the same season, the threads resolve one another. The three threads are 1) Larry putting a condom on the wrong way and giving Cheryl a numb vagina; 2) Larry’s secretary Antoinette having a problem with her boyfriend, which causes her to fall apart on the job and then to threaten to quit and expose Larry’s “web of bullshit” to the world; 3) Larry almost hitting Jeff’s dog Oscar with his car, which emasculates Oscar. Wandering Bear, a Native American yardman, solves problems 1 and 3 — he cures Cheryl’s vagina and de-emasculates Oscar. Meanwhile, problem 1 solves problem 2, since the numbing agent on the condom, when applied the right way, solves the premature ejaculation of Antoinette’s boyfriend and saves their relationship and keeps her from quitting.

It’s these tightly-wired, Rube Goldberg-ish contraptions that, I believe, are the real heart of the show. It’s a very similar style of writing, by the way, to O. Henry or Saki, who rely also on a pristine sense of geometry. Curb isn’t a status-based show in the way that Blackadder or Fawlty Towers are status-based, but status is important. Part of the trick is that Larry is actually higher-status than everyone around him — with the exception of Jerry Seinfeld and, in a way, Cheryl. As The New York Times once put it, “One of the subtler jokes of Curb is that Hollywood can never get rid of Larry.” And that means that Larry, always, is in a special category — nothing bad can ever happen to him, which means that we’re free, always, to laugh at his misfortune. Richard Lewis is one of the few exceptions to Larry’s high-status, which accounts in large part for why Lewis is always so enchanting to watch. Larry has had a better career, but that is counter-balanced by Lewis’ success with women, and when they meet it’s very often a kind of suspension in the airtight geometry of the show and, in an odd sense, comic relief from it. Lewis has his various neuroses that can slot into the structure, but their meetings are often something very close to pure play — the two of them trying to out-banter the other, and with both of them sometimes seeming to tire of comedy altogether and preferring to talk about history or sports.

Part of the mythology of Curb, like Seinfeld, is that it isn’t ‘about’ anything, and Larry’s particular psychic disorder is to get fixated on the trivial. But there is ‘meaning’ studded within it. Part of it — and this becomes obvious watching the show years after it first aired — is that it really is a kind of chronicle of the neurotic and slightly pervy inner history of our era, and a memento to all these different (easily forgotten) technologies. Yes children, there was a time when everybody had problems with the service on their flip phones, meaning that calls would sometimes drop out just when important information was being delivered. And, yes, people used to have physical porn stashes and had to make pacts with their friends to sneak the porn out of their houses in case they should suddenly die.

It is also, of course, a document of a certain era for American Jews — completely assimilated, very successful, but somehow a little different from everybody else. That’s the gist of so many of Larry’s arguments with Cheryl: that Cheryl thinks it’s nice to have a drink before going to a different place for dinner; that Cheryl likes having dinner parties in which the conversation never moves beyond small talk — and Larry is basically always bored unless people are laughing or fighting.

The other point of the show — and this emerges only after a long period of time — is the idea that this American Jewish sensibility is, actually, a great cultural unifier, one of the only things that everybody can agree on. This came through surprisingly directly when Larry, amalgamated with Bernie Sanders, launched a kind of neurotic bid for the presidency on Saturday Night Live in 2016. Curb had always been set up as the edgier version of Seinfeld: where Seinfeld had virtually no black characters, Curb leaned into race, with Larry endlessly misstepping on race and the show seeing what it could get away with. And the amazing thing is that, even airing in the teeth of cancel culture, Curb was largely unaffected. The truth is that Leon plays into all possible stereotypes. That Larry is actually pretty homophobic (see ‘The Special Section,’ ‘Club Soda and Salt,’ ‘The Five Wood’). And the show sometimes does push things pretty far on race. But nobody seemed to have the heart to even think of canceling Curb.

In the end, cancel culture did get to Curb — Season 10 was largely an unsuccessful effort to tackle it head on — but what’s remarkable is that the show lasted as long as it did. Everybody in it had long passed their ostensible cultural moment. Everybody was getting old. The jokes, more and more, dealt with the very “first world” problems of well-heeled, old white people (country club memberships, seating at dinner parties, etc). But the show just continued to sail forward. The real point is that — even in a very puritanical era, even with everything in the culture scrutinized for being insufficiently representative, for tonal missteps — the culture as a whole couldn’t help but respect the craft in Curb. It was just so well-observed, so well-knit-together, so well-acted, that, even with so much of the culture playing it safe, Curb was allowed to see just how far it could push.

Pretty, pretty, pretty, good Sam.

My wife and I were extras for a day on Curb (charity auction). Because my wife had become friends with Susie Essman we were introduced to everyone. I was starstruck. It was the Seinfeld reunion. I got to meet Julia Louis-Dreyfuss and we got a lift back to where we were staying with Cheryl.

We were on camera walking behind Larry and Jeff for three seconds. Season 7, episode 10., around 4:20. All three of my kids said my walking was bad! I was a little lopsided.

What struck me most about the day was the intense iterative process. How they would do improv, but keep refining it and trying new things. I think we saw the making of the first episode with Mocha Joe.

One of the more amazing things about Richard Lewis is that he retained some of his stardom even though he hadn't performed standup or led a TV show or movie in thirty years.