Dear Friends,

I’m sharing a ‘manifesto’ — a discussion of how fear operates within workplace institutions. The partner site

features a piece by , who has a very cool series of ‘one-minute-memoirs’ on her Substack.Best,

Sam

ON THE FEAR CULTURE

I was working in what seemed to be a very cool industry — everybody I talked to seemed to be envious of it — but when I was actually in the office I noticed something funny: everybody there was constantly terrified.

I was in my mid-20s at the time, learning office subservience, and it was sinking in for me that accepting a hierarchy was part of a job. But something else seemed to be at work. By the logic of hierarchy, I assumed that the people above me in the ladder — the producers in this case — would be able to be more relaxed at work, they would have more money, would be able to lord it over people in my cohort. But that wasn’t the case. The producers were the most skittish, the most obviously terrified. Over drinks with my own group — we were actually fairly relaxed — I started calling it “the fear-based production personality” and over many rounds of drinks we unsuccessfully tried to work out what that was based on.

Reflecting on it years later, the ‘fear-based production personality’ strikes me as having less to do with any of the usual suspects and more to do with something in the culture. It wasn’t really about money — everybody in the industry I was in made enough but not a ton: almost no one who was truly financially insecure would ever have gotten into the industry in the first place. The older people with kids did seem to have an extra kick of fear guiding them — they were less likely to argue in meetings, for instance — but, really, it didn’t have to do with that: the producers in their 30s, at an intermediate stage in their career ascent, seemed to be the ones who were most obsequious, most OCD about unimportant make-work details, most likely to throw subordinates under the bus. And, when I think about one of the most irrational exchanges of my life, it becomes more clear to me that money isn’t exactly the determinant it’s usually perceived to be. I was talking to somebody I’d gone to high school with, who works in finance, about somebody else I’d gone to high school with, who’d become the principal of a public high school. The person who’d gone into finance, who was from a relatively less well-off family, said of the principal, “Well, she can afford to do that.” In her finance-addled mind, finance (and a big house in the suburbs) was the bare minimum of what a person needed to survive. Being the principal of a public school was only conceivable as the luxury indulgence of someone born into a rich family.

People weren’t really afraid — and making choices out of fear — because they thought they might go broke. They were making their fearful choices because what mattered to them was prestige, and they felt that it required unending vigilance to stay close to prestige; that expulsion from it was worse than anything.

At the time I was breaking into production, I didn’t think all that much about the fear culture. It seemed like a quirk of my seniors at the company. It made me question whether I really wanted to continue in the industry. But I thought about it far more seriously with the breakdown of liberal values in the period around 2020, the complete unwillingness (by highly-educated, highly-credentialed people) to in any way question the wisdom of one-size-fits-all mass vaccinations, of extended school shutdowns, of ‘mostly peaceful protests.’

At the point when Bari Weiss, then an opinion editor at The New York Times, turned apostate, she had a very clear-eyed sense of what had gone wrong in the mainstream culture. In a coruscating piece for Commentary, she wrote: “The refusal of the adults in the room to speak the truth, their refusal to say no to efforts to undermine the mission of their institutions, their fear of being called a bad name and that fear trumping their responsibility — that is how we got here.

I remember a shock of recognition when I read that piece. What Weiss was describing as ‘fear’ I’d encountered in a very different guise — as ‘maturity,’ as ‘the way the world works,’ etc. The world had fundamentally seemed so benevolent when I was joining the workforce in the 2000s and 2010s — everyone had Steven Pinker and Malcolm Gladwell somewhere in the back of their mind. The premise was that we were spoiled beyond belief, it was a joke how good the world was and how good the underlying system was that kept the world running (a combination of science and the managerial-professional class) and with a few simple hacks it could get even better. But, with the woke outrages of the late 2010s and the early 2020s — the seamless way in which venerable liberal institutions became suffused with progressive ideology, the general disregard for science for the sake of a feel-good consensus (I’m thinking, for instance, of the med school professor who apologized for using the term “pregnant women,” which implied that “only women can get pregnant”), the pattern of institutions caving to demands from the most extreme of their constituents — the system started to register as far more hollow than it had. And much of the issue, it transpired, was with the promotion mechanisms for those who’d ascended to positions of power within venerable institutions. As Bill Deresiewicz put it on the Persuasion podcast, “Why won't [authority figures] stand up for what their institution is supposed to be about? Well, because they haven't kissed this many asses, and clawed their way up the greasy pole, just to lose their job for the sake of some damn ideal or belief.”

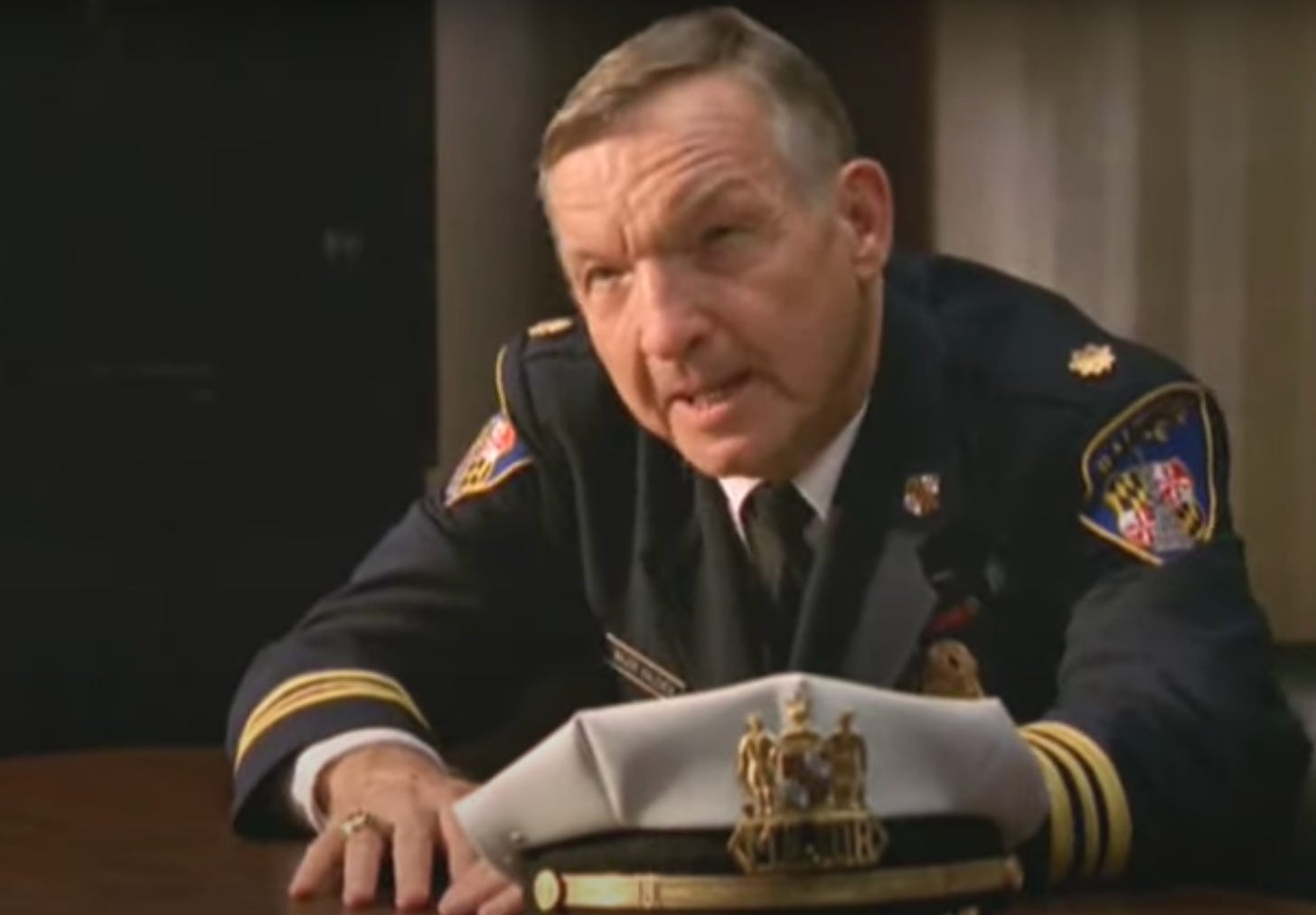

It was a very startling moment of noticing that the emperor had no clothes on. These institutions seemed so entrenched, had such wonderful ideals. The administrators were such apparently well-credentialed people who had risen up through the meritocratic ranks. But, on closer inspection, it turned out that the mechanism for advancement wasn’t really merit; it was fear. People letting their superiors know that they were no threat, that they abided entirely by the rules of the system, and then backing into the next highest rung on the ladder. For artistic examples, the rise of Valchek in The Wire, the ass-kissing ascension of Lyndon Johnson, as documented by Robert Caro, the promotion of the inept Stanley, as discussed by Norman Mailer in The Naked and the Dead, are all paradigmatic. What’s analyzed there — and something I discovered myself in my production offices — is that fear is encouraged and prized. It lets superiors know not only that subordinates are deferential to them but that subordinates believe implicitly in the system, that their horizons don’t extend beyond it. In the self-confident nonchalance of Red or Wilson in The Naked and the Dead, in the independence of Daniels in The Wire, in the aristocratic disposition of Johnson’s rival Coke Stevenson in Caro’s Means of Ascent, there’s a quality that those in power don’t like — inner resources, integrity. People like Red, Daniels, Stevenson aren’t in terror of power and therefore aren’t beholden to it, and power, with its ineffably sharp senses, doesn’t like that and avoids the better person for the one who’s more malleable. Multiply that phenomenon enough times and you started to end up with a very hollow society — a lot of hacks who had ascended the ladder by means of fear, were in constant fear for their positions, and at the moment of any crisis (real or perceived) would sell out the deeper values of their institution for the sake of expediency.

In the last year or so, the dial has turned a bit. Institutions seem to have realized that they can’t rely on their expediency-minded hacks. People like Joe Kahn at The New York Times and Jenny Martinez at Stanford Law School have, ringingly, reaffirmed underlying institutional principles and stood up for those values in the face of criticism. It’s been an important lesson for the culture-at-large — and it’s unclear how deeply it’s been taken in in the institutions themselves. Underneath the guise of ‘meritocracy’ is, very often, the fear culture — going along to get along, climbing up the greasy pole, risk-aversion, etc, etc. When times are good, the pretense can last for a while. But in a crisis, the hollow administrators are exposed for what they are, and the whole structure — based on fear — turns out to be more fragile than anybody would suspect.

When I was in a quite different profession in corporate America, my idealism and my ethics were consistently threatened to the point that I stood up against the lies and said privately this: "Life without dignity is not worth living" -- It's a story, but, know this: I got out with my heart and spirit in tact.

This, sadly, is now the state of higher ed. To speak this truth, usually, you must leave the profession: "The refusal of the adults in the room to speak the truth, their refusal to say no to efforts to undermine the mission of their institutions, their fear of being called a bad name and that fear trumping their responsibility — that is how we got here."