Dear Friends,

I’m sharing a ‘manifesto’ - i.e. a more politically-themed essay. This is an attempt to get at some more rational, ‘centrist’ understanding of the loaded term ‘red-pilled.’

Best,

Sam

ON RED-PILLING

It’s a memorable scene and image. Neo, after some perplexing adventures, finds himself in a sparsely-furnished room with a glass of water in front of him. Morpheus holds out two pills for him, says, “You take the blue pill, you wake up in your bed, you believe whatever you want to believe, you take the red pill, I show you how deep the rabbithole goes.”

And then about five years ago, through Curtis Yarvin, the term ‘red pill’ entered the political culture and came to mean the moment of truth — do you live in your blinkered, cozy blue-pill reality; or do you see things for what they are?

If you think about it, it’s not really a perfect analogy. The Matrix is, after all, a sci-fi movie, and, y’know, the reality is not that we’re all hooked up to agricultural feeders that harvest our bioelectricity with our waking life a carefully orchestrated simulation. Believe that the ‘red pill’ is reality — and this seemed to be the mistake of the alt-right and the current round of crazies — and you start to believe that the most far-fetched, conspiratorial explanation must be true.

But within the domain of red-pilling, there were, I felt, two complicated, valid ideas being grappled with — and part of growing up, for me, meant taking them on.

One idea was that governments — or the powers-that-be — tended to see themselves not as an extension of the public but in opposition to it. As far as I could tell, this was just something inherent in the nature of power — power’s tendency to consolidate and enclose, which meant above all protecting itself and then keeping those outside power either from accessing it or knowing what it was really doing. War was of course the perfect distillation of power — and both the exercise of war and the exercise of propaganda to keep hidden the truth of war, was the underlying domain of governments. The more I understood about history, the more that certain conflicts — say the Hundred Years’ War or the Thirty Years’ War — weren’t ‘wars’ in the way that we usually understand them, aberrant events directed in pursuit of a specific objective. They were more a way of life — an army pillaging every year during the ‘campaigning season’ — and were understood to have all sorts of benefits for the ruling class. At the time of the Hundred Years’ or Thirty Years’ War, the dominant nature of rule was fairly transparent, but it was a myth (the logic of the red pill went) to believe that anything had fundamentally changed because of democracy or the Declaration of the Rights of Man. Vietnam was clearly in that same category, Iraq too — and wars like the Falklands almost comically so. Simply put, governments liked wars. They were good for business, good for testing out new technologies, and, most importantly, they consolidated power with wonderful efficiency, cowed dissent, kept the society complacently buzzing along.

The belief was that representative government served as an antidote to that sort of militaristic mindset, making those in power an extension of the civilian population and accountable to them. But it had become completely clear, by the time democracy spread around the world, that that wasn’t the case. Whole branches of government seemed to disappear from public view; what was revealed of its operations were clearly lies; and the representative government either struggled to exert any kind of hold over a sovereign bureaucracy or else, far more frequently, didn’t try at all — and went along with a power structure that seemed eternal and unaccountable, that was forever closed to the public and forever dreaming up new schemes to make its grasp of power even tighter. In recent history, the CIA is the most obvious instance of this phenomenon — the president’s loyal intelligence agency slipping the leash in the 1950s and creating a kind of global shadow government, fixing elections, fomenting coups, sometimes working loosely on behalf of the ‘crown’ of the United States, sometimes evidently pursuing its own interests. For a long time, the CIA’s endeavors in the ‘50s and ‘60s were dismissed as a ‘conspiracy theory’ — itself a term advanced by the CIA. By the ’70s, it had started to become clear that many of the most outlandish rumors attributed to the CIA were more than true — and the sense now is that we will never really know the extent of the CIA’s operations towards the peak of the Cold War. But the CIA is just an example, and the best, least-red-pilled American history I’ve read — say Robert Caro’s LBJ books, Barton Gellman’s Angler — are, while remaining completely within the domain of a research-based, ‘mainstream’ approach, depictions of the limits of the democratic process in exerting any kind of control over the real apparatus of power.

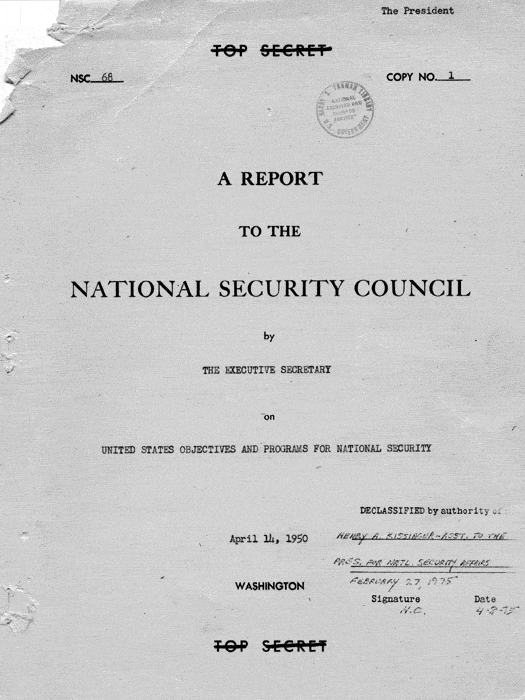

For somebody like Yarvin, the takeaway is that democracy is a sham and fool’s game, and that it’s really easier all around to just skip a step and be avowedly a ‘royalist.’ And, in the political space, that’s much of what red-pilling looks like — an idea that elections are very, very surface, that the real business of government is in things like NSC-68, which with no democratic discussion whatsoever set policy for the U.S.’ policy during the Cold War; in the sort of black ops occasionally exposed by journalists like Seymour Hersh and Jeremy Scahill but basically kept completely under wraps; in the bipartisan consensus around the nearly trillion-dollar Pentagon budget, of which the majority of funds is virtually unaccounted for. This was the left-wing critique of government throughout the Cold War. It’s now most associated with a right-wing libertarianism, but the critique is essentially the same — that government is power (predominantly militaristic power), and that all the liberal emollients, a ‘free press,’ regular elections, etc, have the accumulated effect of whitewashing and legitimizing raw power.

I don’t have any great answer for that. I’ve been going through my own shock in the last few years, realizing how dexterously the powers-that-be manipulate the media; and I’ve been developing a better understanding of how deeply entrenched the ‘security state’ really is, how consistent of a force militarism has been throughout human history, how eternal it appears to be. What’s worth saying about it, though, is the the emphasis placed by militarism on shutting up the public, on avoiding the press, etc, are all revealing. That system depends on money and depends on compliance — which means that, somewhere in there, the system does connect back to the democratic process. It’s completely possible that the democracy has lost its nerve — that, in America at least, the transition from republic to empire occurred some time ago and that there is no turning back — but that does not mean that democracy, all by itself, is invalidated. There have been times when military budgets have been pulled back, when wayward intelligence agencies have been reined in. We’re not doing it now, but I suspect that that’s more our issue than the fault of democracy itself.

The other leading source of red-pilling was an emphasis on nature over nurture — a belief in biological determinism and evolutionary biology, and, above all, a sense that inequalities emerged biologically and couldn’t be smoothed over by goodwill or progressive orthodoxy. This perspective flared up in topics like IQ but was most acute in discussions of the sexual marketplace. In a highly-controversial chapter of 12 Rules for Life, Jordan Peterson laid out the crux of this argument. “Instead of undertaking the computationally difficult task of identifying the best man, females outsource the problem to the machine-like calculations of the dominance hierarchy,” Peterson wrote. “They let the males fight it out and peel their paramours from the top. This is brilliant strategy in my estimation. It’s also one used by females of many different species, including humans.”

As often as not, when we’re dealing with the contemporary phenomenon of red-pilling, we’re dealing with a variation of this argument — that the sexual marketplace in nature (Peterson, famously, traces this back to the lobster) is heavily built around patterns of dominance and submission. In the manosphere and the incel world, discussion of dominance and submission — taken as facts of human sexuality — are inevitably a prelude to learning to be more dominant, rewiring oneself from the nice-guy template of the liberal paradigm to be dominant in a way that’s in keeping with the exigencies both of the sexual marketplace and of the power structure.

And the empirical evidence of our era does, it must be said, largely point in that direction. Tinder is like a data set for the red-pills — proof, if more proof were needed, of the deep unfairness of the sexual marketplace in an ostensibly enlightened, egalitarian age. And figures like Trump and Bolsonaro — Trump alpha-ing himself on the stage of the Republican primary debates, comparing his dick size to his rivals — are potent testimonies to the ways that playground dominance can break through and shatter every possible democratic institution, every effort to instill some greater principle of maturity in public life.

But Peterson, contrary to popular belief, is not actually an advocate of the ethic of playground dominance — and here he parts company from Yarvin and the red-pilled manosphere. Peterson, describing himself as a ‘classic British liberal,’ argues that conditions of dominance are part of reality and part of our biological heritage but that they do not result in any normative constraints on our behavior. To have any sort of virtue — any benevolence, any notion of equality — it is necessary to rigorously train oneself, to exercise a constant vigilance.

That’s more or less my own perspective. I do get red-pilled sometimes and do sink into depressions because of it — the feeling that power is inexorable, that human beings in their social and sexual relations are almost strictly status-oriented. But, as Mama Gibbs puts it in the cemetery in Our Town, speaking to a shade going through a very similar rant: “That ain’t the whole truth Simon Stimson and you know it.” Human beings are also capable of benevolence and of real unconditional love — the question is how to get there and how to get there on something like a society-wide level.

I actually am a liberal in that I believe that something remarkable happened in liberalism — speaking from a very broad historical perspective — that brought society much closer to democratic systems and to a principle of social equality than our evolutionary biology or status-oriented disposition would suggest is possible. “It’s a bloody miracle,” says Peterson in discussing how things work as well as they do and in how much progress has really been made over the liberal centuries.

The sense at the moment is that something has gone profoundly wrong within the liberal project. Liberalism has allowed itself to be overtaken by a progressive orthodoxy that has lost contact with some basic realities of human existence — the realities of biology, of power structures, etc, the sorts of harsh realities that the red-pilled so gleefully point out. Conservatives tend to take this topic in an interesting direction. The focus of people like Peterson or Charles Murray is on the breakdown of the family structure and on the vision of marriage-for-life. The theory is that that structure overrides the inherent inequality of the sexual marketplace and fosters, over the course of the married couple’s life, some sort of civic virtue. I’m a little more skeptical of that idea — the consequences of repression are not to be underestimated — but it is an interesting way to think about what is happening in the society. As the family structure breaks down, the status-oriented system of the sexual marketplace becomes the sort of operating system for the culture as a whole. “Whether love still exists is the question of our time,” said Michel Houellebecq plaintively in his Paris Review interview. In a searing video on the corruption of Putin’s Russia, Alexei Navalny claimed, basically, that beneath all the graft was the problem of the sexual marketplace — everybody benefitting from Putin’s largesse had mistresses and every one of them needed an apartment and a yacht, “and truly it goes on and on,” said Navalny; an interesting link between the red pill of the exigencies of the sexual marketplace and the red pill of the corruption of an entire system of government.

At the moment, it seems nobody has much of a solution for anything. Liberals are tethered to a belief in inexorable social progress — which bears little resemblance to the harsh power dynamics of life as people actually live it. Conservatives are nostalgic for a family structure and set of values that is long gone and unlikely to return. The ‘red-pilled’ seem just to be nihilistic, to tap into narratives of pure power and pure dominance without any particular moral sensibility. The place I would like to get to, at least in my political comprehension, is a pairing of the harsh truths of the ‘red-pilled’ with the old-fashioned moral sensibility of traditional liberals and conservatives, the idea that various institutions, various social structures, are needed to right the inherent imbalances of power and to bring out the better angels of our nature. But, more than that, we need to believe in our higher selves — to accept much of the critique of the red-pilled but to work assiduously to be, as much as we can be, the best versions of ourselves.

The Romans went through much the same societal breakdown several times over based on these same principals on some level. Basically power-wealth-sex cycled through their society slowly devolving over 5 centuries into compete self immolation. The Barbarians were NOT responsible and only provided the coup de grace to a rotten corpse of a corrupt society. One great example is the first three emperors Augustus - Tiberius - Caligula. Here you can see many similarities to the American decline through unhinged power dynamics and yet the first century only needed 12 emperors but combined the third and fourth centuries needed 50 emperors as they cycled through the corruption at increasing speed. Rome was sacked in the beginning of the 4th century and basically ended their world dominance. We’re witnessing 500 years of much the same breakdown in less than 100 years but the path is much the same and quite similar in many respects.

Interesting. This is about as sympathetic a contemplation on red-pilling as I would expect from anyone who isn't red-pilled. I'm politically liberal but temperamentally conservative so I pretty much fall in line with Sam, both in acknowledging the grim self-gravity of the war machine (my Berkeley days coming out) and in the reality of physical/biological limits to our grand societal project.

My one quibble is that while JPP and Charles Murray might claim to call for elevating our higher selves over our biological proclivities, my limited consumption of their interviews gives me a sense that they ultimately fall back to gravity and create an enervating influence for discouraging attempts at structural change. Of course, their partisan culture warring makes it particularly difficult to take anything they say seriously (I've tried).

During the pandemic, I finally sat down and read the Analects of Confucius. It's an interesting work revolving around maintaining proper relationships. The development of the philosophy over the millennia of empire did not go well (another example of the grim-self gravity of a self-perpetuating bureaucratic machine), but the Analects themselves are actually kind of liberating in a weird way. By creating limitations via strict relationship ties (but not necessarily in dogmatic codes of context) the sayings of the master creates an obstacle course to exercise creativity in managing our relationships with each other. Not that I'd want to be mistaken for a Confucian, but it might be an example of how acknowledging some limitations (as opposed enforcing a radical blank slate) may be the way forward for the liberal project.