SHEILA HETI’s Pure Colour (2022)

I was mis-led to this book by an article in Liberties Journal in which the critic Jonathan Baskin contended that art in the Trump-and-woke era had turned into a sort of pitched battle between the ethicists (the ‘fixers’) and the aestheticists and attempted to requisition Heti on the side of art as “the quietly crusading artist that she has always insisted she is” and her art as “in conversation with the moralization of culture that her critics and commentators have more often fallen victim to than managed to identify as one of her main targets.”

I liked Baskin’s essay quite a bit – which I discussed here – but it is utterly wishful when it comes to Pure Colour, which I was really appalled by and can only see as a symptom of just how broken our aesthetic culture is.

The approach of professional critics has been to treat Pure Colour as a kind of practical joke Heti plays on her own fans. In Dwight Garner’s telling, Pure Colour helps to move her away from the kind of “vast audience” she had been “approaching” and to return to her fabulist roots. Baskin is maybe the most extreme in seeing her as a kind of political subversive tweaking the ‘fixers.’ The majority of critics just chalk up the disastrousness of Pure Colour to how zany and ‘genre-bending’ Heti is – the oh you know artists defense. According to The New Yorker’s rave, Pure Colour has the great merit of “being written as if to foreclose literal-minded apprehension” – and its “weightlessness is noted with wonder not censure.” The Los Angeles Times meanwhile is ecstatic at how “not quite fully formed” Annie, the secondary main character is – since, if she does not feel like “a real person,” well, after all, “neither do lots of people we interact with fleetingly.”

It's this kind of thing that makes you never want to read a book review again. There are a couple of issues here. One is that Heti, for some reason or other, has reached a place in her career where she is apparently unassailable. The other is that Pure Colour gives the impression of portentousness, of having something important to say. I have to admit that I was taken in for the first fifty pages or so. I liked the parable of the bird, fish, and bear that opens the novel and I was intrigued by the structure, the pairing of Unbearable Lightness of Being-like philosophical aperçus with some kind of come-one-come-all campfireish storytelling. But somewhere in there the real terribleness of the prose caught up to me – “even if they weren’t as close as two people could possibly be, still they were sitting at the very same table, and that was pretty good” or, most conspicuously, “she had felt her father’s spirit ejaculate inside of her, like it was the entire universe coming into her body, then spreading all the way through her, the way cum feels spreading inside, that warm and tangy feeling.”

The reviewers, by the way, went through some remarkable somersaults to justify that sentence – “To each her own…you have to admire the leap” is The Guardian’s verdict – and it’s very odd that professional critics can’t just recognize dreck as dreck. But, from there, it gets oh so much worse. Heti’s portentousness leads her around to a variety of different topics – history, theology, art, the internet, time travel, grief, sex, the environment – and, in every case, we get the philosophical musings of a very small child. Of history, it’s pointed out that in the bronze age “they didn’t call it the bronze age, they called it modern times.” Of the initiation to sex and jealousy, it’s noted that “[Mira’s rival] wanted something from Annie, it was something warmer than what Mira had wanted.” Of the fate of art in a post-apocalyptic landscape, the concern is raised that “I think the thing you’re worried about is that our art won’t be appreciated by the woolly mammoths.”

It is very difficult reading lines like this – or the entire section, which dominates the second half of the book, of Mira crawling into a leaf – and to not think that Heti is taking the piss, that she is bringing some aesthetic or other to the point of absurdity. But I don’t think she is. I think it’s all earnest and the novel takes up position in three strongpoints that are beyond all rebuke: 1.in a narrative tracking the strangeness of grief 2.in the wide-eyed wonder of a child taking in the world as if for the first time 3.in post-environmental apocalypse rumination, discussing the horrors that human beings, “killing and criticizing,” have wreaked on the world. And the feeling – which everybody reviewing the book seems to have shared – is that we must bow our heads before each of these subjects. The environmental catastrophe is so all-surpassing that Heti can make a barely-literate, not to mention genocidal observation like “the humans maybe don’t deserve to be here because they are so killing….what is lovable is not humans but life” and in our present, deranged political atmosphere that comes across as tough-minded wisdom. And, meanwhile, the posture of wide-eyed wonder leads Heti to such head-scratching conclusions as “There is strife until death, and there are always problems between people, and even when there are no problems, problems are still there. Being alive is a problem that cannot be solved with living.”

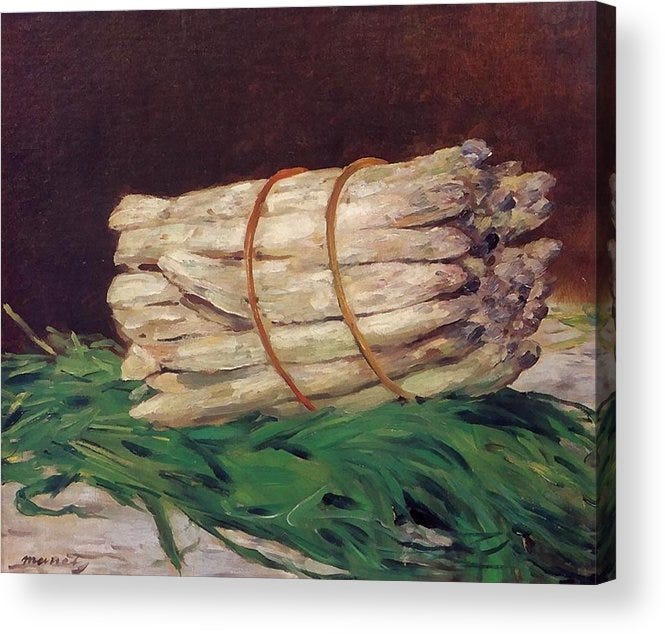

I think I can see where liberal critics were taken in by this – it’s a kind of combination of the moral sanctity of Max Porter or Lidia Yuknavitch with Richard Powers’ perspective-from-the-stratosphere. Slightly more perplexing is what Baskin thought he was discovering in Pure Colour. As far as I can tell, he was fooled by the sections on art – by Heti’s liking for Edouard Manet’s ‘Asparagus’ in opposition to the fixers and to a sneering professor she once had. And there does seem to be some sort of object lesson in here. The artistic debates in our culture have broken down into such simplistic terms – as Baskin rightly notes – that a work of art is immediately enlisted into either the ethical or aesthetic camp. Amidst all the worthy novels crowding shelves, Baskin is heartened to find an ostensibly progressive writer who is skeptical of fixers and who likes art ‘for its own sake.’ But this, really, is not what the argument should be. Being on the side of aesthetics does not mean just appreciating art or kind of unclouding own’s mind with politics. Being on the side of aesthetics means treating art with respect, treating it as a serious undertaking worthy of all of one’s energy. What Heti has achieved in her career is, by contrast, a very peculiar kind of anti-art – an intense focus on the superficial and paired with philosophical rumination so airy as to be virtually incomprehensible. For her, that lack of seriousness is art – a need to never be pinned down, to get away with saying whatever comes into her head. But, for anybody who actually cares, it’s just goofing around.

THOMAS RICKS’ First Principles (2020)

A soothing, useful book. I wouldn’t recommend it widely - its value, I think, is only for those who, for one reason or another, have gotten obsessed with the Revolutionary War era - but, for those who are, Ricks performs a real service, diving into the classical allusions, the sort of thing that makes everybody’s eyes glaze over when they read about this era, and finding that, actually, the classical allusions are sort of the key to the whole puzzle, revealing a frame of reference through which colonial elites could connect with one another and which animated their sense of self.

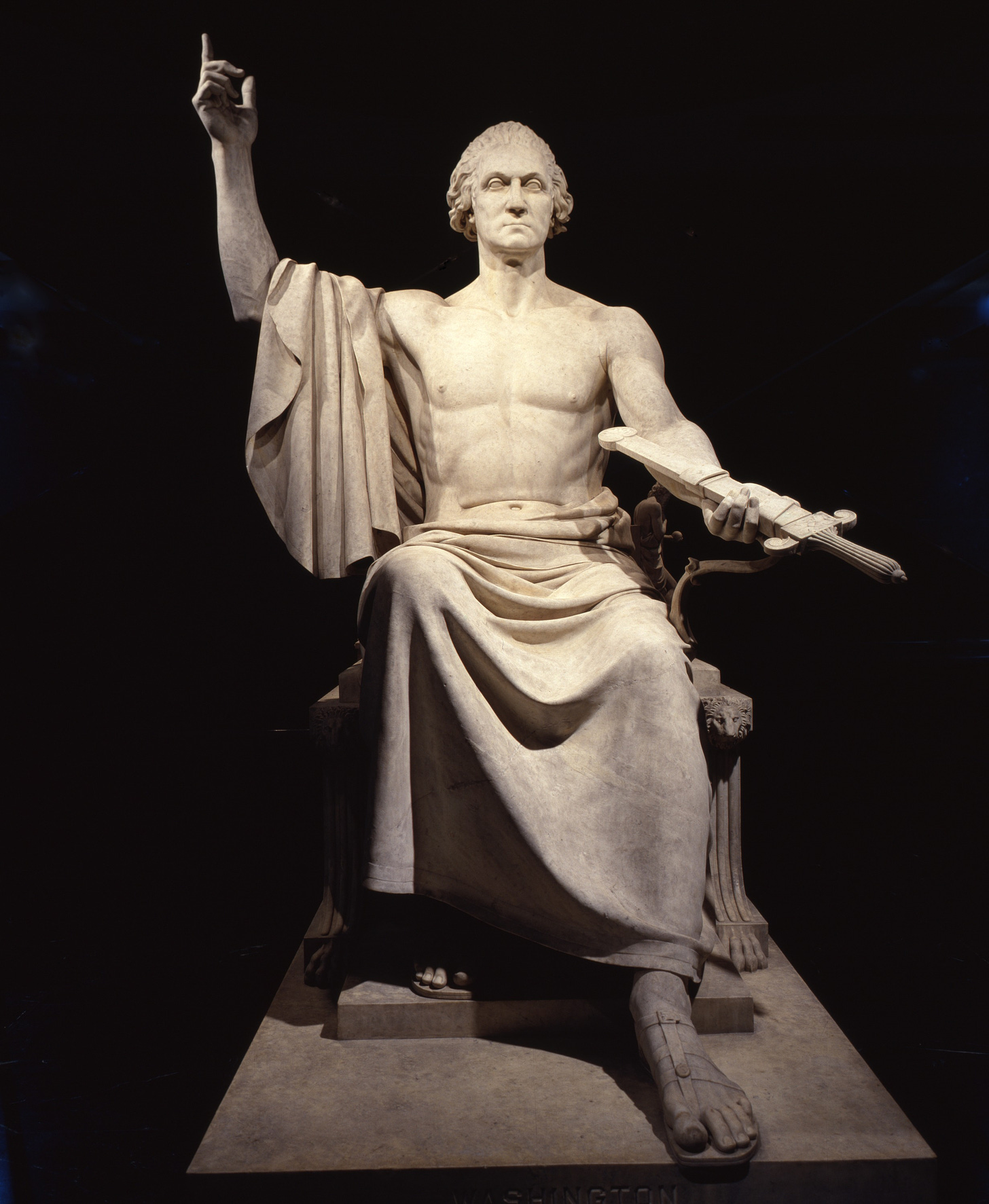

The really critical way to understand this period, in Ricks’ telling, is that Neo-Classicism had spread widely enough that individuals of a particular class viewed themselves almost entirely through the gloss of classical history – which, for them, meant mostly the history of the Roman Republic. It wasn’t, as might have been fair to assume, that the generations of hagiographers to come dressed up the Revolutionary War heroes in togas and classical phrasemaking – the Revolutionary War figures had dressed themselves in togas from the beginning. (In certain cases, this was literal – the Boston firebrand Joseph Warren seems to have donned a toga for a crucial speech in 1770.) Their minds were suffused with classical writers, their ideas for statecraft driven by classical examples that accounted for much of their idealistic bent, and, most importantly, they modeled themselves, often explicitly, on classical heroes – Washington was, successively, Cato, Fabius Maximus, and then Cincinnatus (and driven as well by the negative counter-example of Julius Caesar); Jefferson was, essentially, Epicurus; Madison was a sort of classical lawgiver, forced to improvise when he found, distressingly enough, that the classical tomes skipped over the nitty-gritty of how the famed political systems were actually devised; and John Adams, most touchingly, was Cicero, self-consciously taking on all aspects of the great man, including his flaws, and retaining that sense of self to the end of his life.

The most amusing quotes Ricks digs up are from other figures of the era, less enthused about Neo-Classicism, and telling the elites, basically, to get a grip. In the midst of the Constitutional Convention – with Madison on his high horse about classical precursors - Charles Pinckney archly replied, “The situation of the people of this country is distinct from either the people of Greece or Rome or of any other State we are acquainted with among the ancients.” More trenchantly, the anti-Federalist Amos Singletary, a miller, complained that all the classical allusions pouring out of the Constitutional Convention was just slick lawyers’ talk designed to pull wool over the democratic process. “These lawyers, and men of learning, and moneyed men, that talk so finely and gloss over matters so smoothly, to make us poor illiterate people swallow down the pill, expect to get into Congress themselves; they expect to be managers of this Constitution, and get all the power and all the money into their own hands and they will swallow up all of us little people,” he said.

And, within years of the Revolution, the classical sensibility had lost its pull. “One is hagridden with nothing but the classicks, the classicks, the classicks!” wrote Edmund Trowbridge Dana in 1800 – and that was very much part of a dawning populist sentiment, a belief that the American idiom had to be distinctly American and should draw its strength in particular from the frontier spirit. And it was that shift in taste, already palpable with what Ricks calls Jefferson’s ‘Romanticism,’ that would in short order finish off the Federalist Party and create the Jacksonian Revolution as well as the sort of wild, hedonistic American sensibility that became the true national character and which makes, for instance, the ‘American Wing’ of the Met, with all the Gilbert Stuarts and Neo-Classical knock-offs, seem like such a curious antique.

But it was exactly that flight of fancy, distinct to the Revolutionary War generation, that made the whole thing possible. They really had, as they were constantly accusing one another, “taken leave of their senses” – and that madness took root in culture long before it did in practical politics. As Adams intriguingly wrote to Jefferson in 1815, “What do We mean by the Revolution? The War? That was no part of the Revolution. It was only an Effect and Consequence of it. The Revolution was in the Minds of the People, and this was effected, from 1760 to 1775, in the course of fifteen years before a drop of blood was drawn at Lexington.” That spirit was conveyed most distinctly through Addison’s Cato, the defining cultural text of the era. As Ricks writes, “The drama is stiff and almost unreadable to us today. But eighteenth-century audiences expected lengthy declarations and were not put off by predictable plots. They came primed to enjoy the play’s ‘crisp and quotable epigrams and the beautiful expression of worthy sentiments.’” And that sense of worthy sentiment – Ricks makes much of the revival of the idea of ‘classical virtue’ – underlay the speech-mongering and the language of political gesture that characterized the Revolutionary War generation. It was Warren dressing up in a toga for a speech and the costume drama of the Boston Tea Party and the way that Patrick Henry punctuated his ‘Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death’ speech with – a detail that more demure ages have excised from the story – a gesture stripped directly from Addison’s Cato, pointing an ivory letter opener towards his chest as he reached his climactic line.

In addition to condoning the grand-and-not-exactly-sensible gesture, the Neo-Classicist emphasis had two critical consequences. It was the outer garment of the Enlightenment. This became – as Ricks details – the intellectual basis for, in particular, Madison’s treatment of political science, which is really the critical component of the whole Constitutional project, his rummaging around in classical examples and applying to them the highly-logical methodology of the Scottish Enlightenment. And, probably most importantly, the Neo-Classical tendency developed a shared language among elites. Our more cynical age tends to view the delegates to the Constitutional Convention being united as bourgeois ‘property-holders’ and by their either tacit or overt acceptance of slavery, but the reality of the 1780s was that their differences in outlook, particularly in regard to economics and to regional sensibility, were more dramatic than their similarities. What they had in common was a reverence for classical models. This was, writes Ricks, how Madison – who at the time had no particular fame or accomplishments to speak of - was able to assert such a critical role in the Constitution’s ‘framing.’ “He not an impressive speaker, he was not physically imposing, he was not even a notable writer, but he was knowledgeable,” writes Ricks. And the sorts of questions that Madison was knowledgable about, which were not, at first blush, pressing orders of business in the 1780s – why the Amphicytonic League had collapsed so readily before Philip of Macedon, why Montesquieu wasn’t altogether correct in his perception of the role of factionalism in republics – turned out actually to be the key issues in devising a system of government modeled on classical precepts and leavened by Enlightenment thought. The collapse of Constitutional models elsewhere in the world – I’m thinking, for instance, of the fiasco this year of Chile’s Constituent Assembly – makes it clear that the consensus that prevailed in Constitution Hall and then through the ratification process was far from inevitable and was the result, really, of shared body of knowledge and frame of reference.

And the classical orientation of the era served as a highly-convenient alibi for the revolutionaries. It gave them an authority distinct from their allegiance to the crown. As Ricks writes of George Washington’s emphasis on ‘honor and reputation,’ and self-modeling on Cato, “Today, that approach to life may seem profoundly conservative, but in the eighteenth century it carried a whiff of egalitarianism….Justifying by virtue is a way of escaping hereditary control.” The Romans had been republican and, if the Roman example was ascendant over recent custom, then that made it a ready-at-hand argument for “dissolving political bands” and for creating a mode of government that had been sanctified by antiquity. And in the fast-developing chain of events of the rebellion and of the ratification of the Constitution, it was possible for the founders to forget just how radical what they were doing really was – and, through the imprinting of the classical era, to imagine instead that they were restoring a fallen tradition. And that appeal to classical precedent proved critical in all sorts of tactical ways – maybe, above all, in the invocation of Fabius Maximus to justify George Washington’s hit-and-run strategy during the Revolutionary War. It would have been easy for a detached observer to see in Washington’s military strategy a simple matter of running-away from battle – or else guerrilla tactics that he had picked up on the frontier – but in the classics-mad sensibility of the times he was doing no less than repeating the hallowed strategy of Fabius Maximus in the war against Hannibal.

But this reliance on classicism inevitably posed a problem – how to deal with the fact that the ancients had thoroughly tested various forms of democratic and republican government before concluding, pragmatically, that they simply did not work. And this turns out to be the crux of Ricks’ account – the period Madison spent in the 1780s diligently attempting to square the circle. “In 1784, believing that the Articles of Confederation system was doomed, Madison began to contemplate the problems of ancient Greek confederacies,” Ricks writes. “He had several questions on his mind, all relating to the fragile condition of the United States. What had brought down ancient republics? What had made them so fragile?” And, in a surprisingly moving passage, Ricks continues, “Madison sat in the library in his father’s house near Orange, Virginia. And he stayed in that room and read for months and months.”

It was that period of enforced solitude – with Jefferson from Paris acting as the book dealer for Madison’s studies – that, as Ricks convincingly claims, really laid the groundwork for the next two hundred years of American history. Somewhere in there Madison cracked the puzzle. The assumption had been that factionalism doomed republics – and that, as Montesquieu, the great political theorist of the time, had flatly said, “It is natural for a republic to have only a small territory; otherwise it cannot long subsist.” Madison’s insight was to invert Montesquieu – to claim that, actually, size created its own stability, that factionalism could be put to advantage by canceling out extremes and, through an adversarial process that would permeate the civil society, creating a certain pragmatic balance. As Ricks writes of the Constitution, “In a way the drafters used classical thought to escape its influence.” And the resulting polity – for all the appeals to tradition – turned out to actually to be very different from anything that had existed in the classical world. It had less reliance on a self-enclosed, self-perpetuating patrician class, which had been the real glue for the Roman Republic. And it introduced concepts like ‘the loyal opposition’ and the ‘free press,’ as well as the atmosphere of incessant campaigning, that would have struck Roman Republicans very oddly.

What’s so noteworthy about Madison’s insight is that it wasn’t appreciated even by the founders. Adams, in Ricks’ telling, had cloaked himself entirely in classical models. He was, Ricks writes, “the last Roman, stuck in time.” Jefferson spent his old age reading classics and refusing to think about contemporary politics. Washington bemoaned the rise of factionalism in the 1790s and assumed that that meant the death-knell of the revolutionary project – and, in retrospect, the republic’s survival might have been a closer-run thing than it seemed even at the time. Hamilton’s plots of monarchist coups, the rise of ‘our Catiline,’ Aaron Burr, all speak to what’s proved to be a very familiar model, the collapse of nascent democracies after the initial revolutionary fervor and after the demise of the charismatic leader. But, as it turns out, that’s what Madison was ready for – that ‘factionalism’ and the party system would serve as ballast once the spirit of unification wore itself out. As Ricks writes, “A good part of early American history is Madison talking to himself,” and there’s a way of understanding all of American politics as being exactly that – Madison designing a society that appears to be contentious but in which the constant political chatter is just the surface ripples above an underlying order.

I called the passage on Madison in the library ‘moving.’ This is especially so given the clear mirroring between Ricks and Madison – Ricks the war journalist, not actually a trained historian, who, in despair at Trump’s election, retreated to a library in Maine and spent four years reading the founders and puzzling over the question “What is America supposed to be anyway?” The book club-y conclusions he has in an epilogue – ‘What We Can Do’ – turn out to be a bit underwhelming and mask the real insight that Ricks so painstakingly uncovers, which is that the politics of the revolutionary era were largely an exercise in fiction. The founders had a tendency to forget even, at times, their own self-interest because they had immersed themselves so completely in Plutarch that they really believed they were acting out scenes from the later Roman Republic. It’s not necessarily so easy to recapture these pervasive mental landscapes – although right-wing politicians have a tendency at the moment to refract their actions through Hollywood’s golden era, Bannon through Twelve O’Clock High, Reagan and Cheney through the occasional reference to Star Wars; and politicians of all parties have no need really to remember anything about Catiline or Cicero or the Amphicytonic League because they have the example of the founders themselves as their models – but the point is that it is possible to generate dramatic, radical, and, in some cases, genuinely high-minded change through these sorts of collective fictions. The founders were able to extricate themselves mentally from their current circumstances and to both gain their independence and to construct a new nation through appeal to an idealistic abstraction – in their case, a vision of statecraft that they had somewhat selectively derived from the story of the Roman Republic. It’s not exactly clear at the moment that we, as a nation, have access to a similarly shared fictional landscape, but I have the sense that Ricks has really uncovered something and that there’s a lesson to be had here – that our ‘first principles’ have to do with an idealism that is intertwined with a certain collective delusion and that that sort of political idealism connected with an ethic of personal virtue is both at the root of our civic life and remains, in spite of everything, somehow attainable.

And, by the way, the LAST thing I expected from a book review was to learn something fundamental about the way the country is structure.d. Very cool re Madison plus factionalism as the secret sauce for the whole thing. I guess Thomas Ricks gets credit for digging that up. But not something that would have occurred to me. Cheers!

Thank you for this! I've had such mixed feelings on Sheila Heti, especially on How Should A Person Be. I feel like this gives me permission to just feel like she's not very good. I don't know if that's what you meant! - but that's what I'm taking from this! Her writing gives me such an odd feeling and I hadn't even gotten to the 'tangy ejaculate.' Yikes!