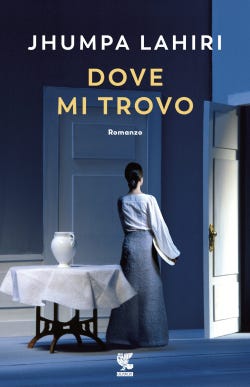

JHUMPA LAHIRI’s Whereabouts (2018/2021)

Elegant and acerbic.

I really resisted Whereabouts as I was reading it – it felt whiny and featureless, like some well-heeled, upper-middle-class matron were giving you the tour of her house, showing you her photo albums, and complaining bitterly about everything she pointed to. The notes I wrote to myself all reflected a certain disbelief about the whole exercise – “the feeling of a slow-moving train grinding to a stop,” “everything in her life laid out as if for a glossy magazine spread,” “somewhat optimistically marketed as a novel,” “how did this happen, how did the reigning wisdom of writing a novel become a series of sparsely-delineated, archly-described irritations” – but I was wrong. It takes a real courage to write in the way that Lahiri does, without effects, locked narrowly into the perspective of her very-annoying, stuck-in-the-water narrator, and to let the narrative energy accumulate very gradually and almost imperceptibly, taking its shape as a direct result from all the details and throwaway comments that make up the novel’s opening sections.

The real subject of Whereabouts is the difficult topic – how do we prepare for old age and death, how do we become habituated to it, how do we make our peace with life when life hasn’t graced us with any particular sense of meaning, what do we do with the desert that constitutes the back half, and most self-aware portion, of our lives? There are many excellent reasons why artists tend to steer away from everything to do with this topic, but in a sense it’s the only story that really matters – and Lahiri has a very cunning approach to tackling it.

The novel opens with a string of complaints – each of the terse short storyish chapters is, essentially, a fresh irritation. There are problems with spring pollen, with the décor of a university office, with the behavior of museum-goers, the vapidity of therapists. There are complaints about the uninteresting ways that other people complain to the narrator, a very long section is dedicated to the disappointment of listening to a married couple argue and realizing that what they’re upset about – taking a cab versus walking – is even more trivial than the kinds of things that upset the narrator. The complaints about external surroundings alternate with self-reproaches. Looking in a mirror is an event – “my face has always disappointed me” – as is a dispiriting exercise lap in the pool: “I’m not a strong swimmer. I can’t do a flip turn, I never learned how.”

The climax (if that’s the word) of the novel’s opening half is an intensely irritating visit by an old friend and her new husband. The husband is very inconsiderate and badly upsets the narrator’s equilibrium. We are treated to the litany of his crimes: he complains a little too insistently about the city the narrator lives in, he studies the narrator’s books too judgmentally, he “eats almost all the pastries I bought with [his daughter] in mind,” he fails, before leaving, to disclose that his daughter had drawn a chalk line, “a thin errant line,” on the back of the couch.

So, trivial to the point of being unendurable – which, actually, is the whole point. What Lahiri is documenting, detail-by-detail, is death by a thousand cuts, the progression of a nervous breakdown by a character who doesn’t realize she’s having one. And each desultory scene is, if viewed in a certain way, an anteroom for the next life – the visit to the beautician with the row of mirrors and the row of women is like being prepared for some kind of Pompeiian death fresco; the bi-weekly visit to the swimming pool is really “an escape from life’s troubles” in the company of similarly remote shades who are exquisitely careful about not interacting with one another; the white chalk line on the back of the couch is, of course, even more evocative than it is annoying.

Lahiri finally tips her hand at the novel’s midpoint. She attends a friend’s dinner party – a cornucopia, needless to say, for fresh irritations. There’s a woman there who “doesn’t bother to look at me when she shakes hands,” who has too many opinions, who dislikes a painting in the host’s home, who dislikes an actor in a film the narrator enjoyed. At which point the narrator snaps – “Do you realize you have no idea what the fuck you’re talking about?” – and realizes that she’s the one in the wrong socially and, worse than that, has crossed some subtle, crucial threshold in her life. “I’ve never exploded like that at a small dinner party among friends,” she reflects to herself.

So – a bad moment in one’s life. A bad realization that this is who one is. And that it can only get worse from there. If my resistance to the novel’s first half was that this felt like Rachel Cusk (or an over-serious Curb Your Enthusiasm), the string of irritations and the narrative train grinding to a stop, what it really is is a coming to terms with all the things that people prefer not to think about until they absolutely have to, turning into one’s parent, facing old age without a partner or children, noticing a new-found immediacy and familiarity with each intimation of death. And in that new awareness, every interaction, no matter how glancing, becomes resonant and takes on a different, and terrifying, charge. Of a deeply dull visit to her mother – who is, unsurprisingly, a world-class complainer – the narrator observes, “I sense she’s telling me her aches and pains as if to say: look, I’m full of glitches, defects, hazards, that might at any moment snatch me away definitively. Prepare yourself, she says every time we see each other. Prepare for the catastrophe.”

And very subtly, very delicately, with wry elegance and sure footing, Lahiri crafts a meditation on the moment when a character passes over from being in life – with attachments and creature comforts and ceaseless irritation with all creature comforts – to being on the other side. For me, that’s the most potent, most significant theme – it’s in Our Town, in Sarah Ruhl’s Eurydice, in John Banville’s The Sea, Michael Haneke’s Amour, I think it’s what people find so impressive in The Magic Mountain and Death in Venice – and it’s a kind of genius for Lahiri to tease it out through the metaphor of a travel narrative. Travel – as the epigraph to Whereabouts reveals – is really a kind of death, a burying of the self, of all of one’s surroundings. And, by employing the tropes of the travel narrative as a vehicle for discussing age and death, Lahiri frees herself from the orchestral atmosphere that accompanies a work like Death in Venice or Saramago’s The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis. Whereabouts manages to be very light, insouciant, pleasantly irritable – to mimic inconsequentiality even as it circles around its great subject.

By the way, I’m not exactly shocked but, as my grandmother would say, miffed by the reviews of Whereabouts in the usual-suspect publications. Basically, nobody got the book at all. That didn’t get in the way of tepidly laudatory reviews of what were seen to be stand-alone vignettes. “Narrative is not what this book is after,” claims The New York Times. “Though plotless, the novel remains compelling as a peephole into a mind sequestered from others. What lies behind the narrator’s unyielding solitude remains obscure,” writes The Guardian. These sentences are far from true, and it’s a bit mysterious what there would be to praise in Whereabouts if it actually were plotless, just a string of pissy stand-alone stories. But Lahiri seems to be one of these writers who is beyond reproach. And the reviewers, who have nothing to say about the book itself, turn veneratingly to the writer – so impressed that Lahiri taught herself Italian as an adult, wrote an entire novel in a second language, and then translated it back to English. That magazine profile-ready piece of information gives critics something to talk about – and the detached tone Lahiri hits in Italian is understood to be a protest against the ways in which she is inherently exoticized in English. “In English, such a vision seems, intractably, a form of white privilege,” explains The Guardian. “Writers of colour know that publishers, academics, even lay readers, bring trite, postcolonial presumptions to their work and load them with the burden of minority representation. Perhaps, in Italian, Lahiri saw the possibility of writing the everywoman English denied her.” Yeah right. Lahiri’s own explanation for the switch in language is very different and very personal - “By writing in Italian, I think I am escaping both my failures with regard to English and my success,” she says - and the reviewer fails to explain why switching to a completely foreign language and foreign market would allow Lahiri to escape from a feeling of being exoticized. Although it is perfectly possible that Lahiri would have tried to switch languages and nationalities to get away from a comment like that – an almost perfect inability of reviewers to deal with what’s in the text as opposed to some armchair psychology of the writer’s motives.

JENNY ODELL’s How To Do Nothing (2019)

Reading this is a very ambivalent experience for me. On the one hand, I’m absolutely on Odell’s side. It’s been dawning on me a little late in the day what the ravages of the ‘attention economy’ are - and Odell is eloquent and thoughtful both in outlining the problem and proposing a solution, which is a sort of judo-like move for regaining control over attention. The techies and the algorithms have found a weak spot in our neural programming, Odell seems to be saying - they noticed how easily our attention could be manipulated and diverted. Well, the path out is to take attention very seriously, to learn to really look, to really listen, to be attuned to context and to place - in short, to create strengths out of all the things that the algorithms exposed as vulnerabilities and in so doing to reclaim rootedness in the world.

It’s a lovely-sounding and probably necessary project and Odell really is an impressive motivational speaker for it. All by itself, the range of examples she comes up with of people-through-the-ages-tuning-out-an-overactive-social-organism makes The Art of Doing Nothing worthwhile reading. But, on the other hand, I’m somehow unconvinced by what Odell is up to. It seems a bit neat and naive - the antidote to the digital dystopia seems to just be to take up birdwatching and then the obsession with tech falls away of its own accord. And it also, I kind of hate to say this, sounds really boring.

I had the odd sensation as I was reading How To Do Nothing of sitting in the pews of some very simple, very tasteful church - that everybody who came up to the altar to speak was beaming, everybody was speaking elegantly and movingly, the hymns were all melodious - and that I just desperately wanted to get out of there. That’s the overriding sensibility from the parade of sanctified performance art that Odell presents for the reader - the Finnish prankster who stared off into space for full days during Deloitte job training; the ‘maintenance artist’ who spent a year meeting and shaking hands with every one of New York City’s sanitation workers; or, most emblematically, the 45 minute ‘show’ on a cliff overlooking the Pacific Ocean in which an ‘audience’ watched the sun set and applauded when it finally went down. That sounds like a perfectly wonderful, admirable activity and it’s also schmaltz in its like purest form. I somehow find it difficult to imagine anything that I’d rather do less.

What Odell stands for is the modem incarnation of Quakerism or a particular quietist religious tradition. It’s a very potent aesthetic tradition - J.M. Coetzee and Nicholson Baker are among its exponents - and the danger within it is this careening towards sentimentality, towards a certain ethical absolutism, an idea that if something is good for you then it must be beautiful and true as well. I remember being very struck by a Baker quote in which he described sentimentality as the ‘third rail’ of American fiction. The implication was that sentimentality - earnestness - was actually the most daring direction to move in in art, that anything cynical or sharp-edged was basically a mode of self-protection and a wave of truly audacious art would luxuriate in sentimentality.

And cue the setting sun.

I have a very difficult time figuring out my own stance towards all of this. My aesthetics are all about sharp lines, insuperable barriers, the sense of inherent tragedy. And I am very suspicious of a school of thought, of which Odell is representative, that says, basically, that we don’t have time for any of that, that the world is too far gone and we need an art suited to our times, which emphasizes intentionality and earnestness even well past the point of being ridiculous. But I have been converted to this mode of thought before - and have overcome various misgivings to dive into the self-help section of the bookstore, read Buddhism and Eckhart Tolle, start using words like ‘present’ and ‘mindful,’ and duly discovered that this whole way of thinking made me happier and probably better, or at least more productive, in my writing.

Still, the art that Odell is advocating for continues to bother me. It’s not just about cleaning up one’s own mind, it’s an art of social engagement, in which ethics leads the way and expression is suited to the moral sensibility of the community. “I am interested in a mass movement of attention: what happens when people regain control over this,” Odell writes - and the emphasis is on ‘mass movement,’ on orchestrated group activities to relearn the lost art of true seeing and true listening. There’s lots of bird-watching, worthy performance art, conscientious connection to ecology and one’s immediate surroundings. The result sounds like the happy ending of a very saccharine movie. In a lyrical passage at the end of How To Do Nothing, Odell writes, “Mak-‘asham, the Ohlone food pop up, opened a permanent cafe this year, and the line spilled out the door on opening day. The migratory birds return each year, for now anyway, and I have not been reduced to an algorithm.”

The mood, as the credits roll, is of sanctity - the tranquility of the quiet and self-sustaining community, the faint notes of a hymn from the parish church.

If I have some difficulty enthusing about this vision, part of it may just be that I’m a New Yorker. As Odell astutely notes in her introduction, “Given my insistence on attending to the local and present, it is important that this book is rooted in the San Francisco Bay Area, where I grew up and where I currently live. This place is known for two things: technology companies and natural splendor.” And How To Do Nothing is very much a West Coast text, with a specifically Bay Area-aesthetic. Progressive politics, worker solidarity, ecology are all seen as intricately intertwined with self-expression and self-exploration. Sentimentality is understood to be an extension of moral seriousness and not at all contrary to intelligent inquiry. And there is a certain messianic, or millenarianist, sensibility, a belief that the unique fate of the Bay Area, as ground zero both for the Age of Aquarius and for the tech dystopia, lends it a particularly authority to divine some way out of our current mess - sort of in the way that it’s not known what the savior will have to say but it’s understood that he or she will come from Nazareth.

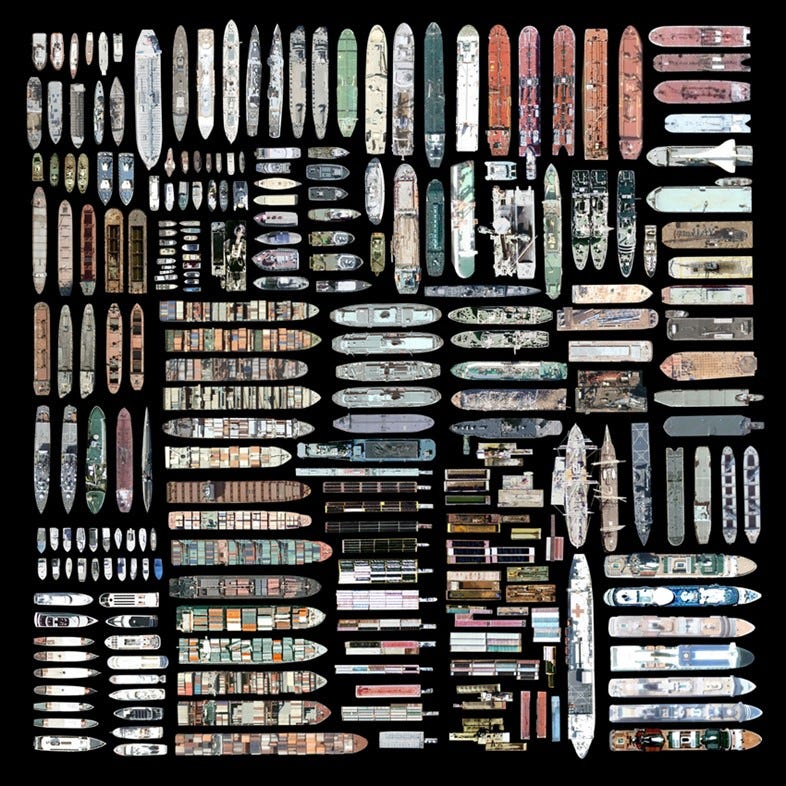

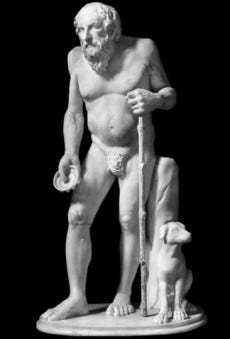

And in terms of prophecy - and I do want to be clear that How To Do Nothing is a religious book - the clearest message Odell has is that salvation will come not from retreating from the world but from a sort of wry participation, what she calls “standing apart,” which is to be distinguished from that other Bay Area prophet Sheryl Sandberg’s “leaning in.” This is the strongest section of How To Do Nothing - Odell’s tracking of the long history of retreats-from-the-world, stretching all the way back to Classical Greece and China, and with the conclusion that, simply enough, they don’t work. It’s an interesting slant on Epicurus and Diogenes to see them critiqued as poseurs, as advocating for withdrawal from the world even as they employed shrewd methods for disseminating their radical ideas. But, from Odell’s perspective, the refuseniks of the Classical Age at least got further than their 1960s counterparts whose utopian communities tended to collapse with spectacular rapidity. Robert Houriet’s tour of the counter-cultural enclaves, as summarized by Odell, makes for depressing reading - with the communities incapable of truly separating from the surrounding capitalist economy and tending to collapse into either an anarchic tragedy of the commons or into some cult of charisma. And same goes for B.F. Skinner’s Walden II, which Odell takes to be a ground truth for how planned communities work and a parable for the whole saga of Silicon Valley - an inevitable shift into a tightly-managed technocracy and dystopia.

Odell may be exaggerating a bit in seeing Walden II, which is after all a novel, as representing the fate of all utopian communities. But I do fundamentally agree with her that retreat is probably the wrong direction. She has a lovely encomium to Thomas Merton, who found a middle path, a way of participating in the society without ever fully being of it, like in a state of permanent internal exile or conscientious objection. And that approach is phrased even more positively in another lovely encomium, this time to David Hockney, in which that sort of wry participation is treated as seeing completely differently - instead of the presentational tableaux featured in most art in museums, Hockney shifts the entire apparatus of artistry to the artist’s experience in making the work. The image, Hockney believed, “contained the amount of time that went into making it, so that when someone looked at one of his paintings, they began to inhabit the physical, bodily time of its being painted.” This principle is further elucidated by Mierle Ukeles, one of Odell’s favorite performance artists, who says “My work is the work.”

I’m convinced that Odell is onto something here. What she’s describing is, basically, a Buddhistic way of being, in which a person can be fully, enthusiastically participant in the social world but is able to retain a sacred detachment and to see the world in idealistic terms, as a manifestation of their own perception. In that case, a work of art, or some strenuous act of public engagement, is not just a contribution to the social whole. It’s an articulation of the self that compels the rest of the society to engage with the individual on their level. The seeing propounded by Hockney or Ukeles is completely idiosyncratic. To take in their work involves participating, for some period of time, in their consciousness, which then encourages the viewer to do the same, to create their own reality which another viewer will participate in. The mode of exchange becomes highly subjective, reciprocal, ecological - and a powerful antidote to the contextless, ‘frictionless’ discourse that abounds on the internet.

That’s a very ancient way of being - of attempting to be always heightened in the present moment, always attuned to the world-creating capacity of one’s subjective perception - and it is as powerful and compelling now as it was in the ancient world. Where I part ways with Odell is, as it were, at a particular historical moment. Odell is very interested in a turn that America took in the 1840s - the turn towards Manifest Destiny and unrestrained expansive capitalism. What she would like to do - and this is a very West Coast and very Quakerist sensibility - is to undo that moment. She calls it “manifest dismantling” - reversing, essentially, everything that happened from that point forward, the genocide of Native Americans, the technological devastation of the environment, the breakdown of communitarian values for the sake of an imperialist philosophy.

I am not saying that Odell is wrong to wish for any of those things, or to wish for a return to the sort of philosophy of agrarian virtue that was wiped away in the tumultuous 1840s. But I just don’t think it’s possible. There was a moment when the world committed irrevocably to modernity and concluded that high levels of technology were needed to sustain large populations - and I don’t think that that trend is any more resistible now than it was in the 1840s. Odell’s sympathy seems to be with the refuseniks of that era, with Thoreau and the Transcendentalists, who attempted a program of civil disobedience against the Mexican-American War and against the broader direction of industrialization. But I just can’t help myself from seeing that program as both regressive and ineffectual. My sympathy is for Whitman, who shared much of the sensibility of the Transcendentalists but fell in love with the propulsive dynamics of the modern city and wrote, “There was never any more inception then there is now, Nor any more youth or age than there is now, And will never be any more perfection than there is now.”

Within Whitman there is a wry detachment, a ‘standing apart,’ a heightened seeing, a paradoxical participation in and withdrawal from the world at the same moment. It may just be a matter of taste, but I prefer that to Quakerish quietism, to the anti-modern withdrawal of Thoreau’s crew. The hope, in any case, is that there is not just one recipe for dealing with the digital dystopia - not just the delete-and-unplug approach of Jaron Lanier, Tristan Harris, and Time Well Spent. If Odell’s standing-apart is one method, ethically conscientious, communitarian-driven, I would like there to be a method as well that takes in some of Whitman’s paradoxes, that is forward-looking but not bound by the diktats of ‘progress,’ that is still with the digital age but not of it.

Interesting, Samuel. I've liked much that I've read by Lahiri, though nothing has matched "Interpreter of Maladies," which I thought was brilliant. Your piece has piqued my interest in tackling "Whereabouts," although the difficult topic you point out might be too close to home for comfort. Who needs comfort?

Excellent article. I just finished Andrew Holleran's The Kingdom of Sand, which sounds in its theme very similar to Lahiri's book, though the circumstances couldn't be more different. Also, sounds vaguely like Rachel Cusk's trilogy in its single-minded self-focus. Anyways you made me want to read it, so now that's on your conscience! Tried to read Odell and stopped. As I recall the beginning waded deep into academic thinking, as if she needed authority to discuss something as universal as life experience. Fun illustrations! Wasn't miffed once!