KATIE KITAMURA’s Intimacies (2021)

Oddly tentative. A bust.

Kitamura seems to hint at three different narratives without following through on any one of them. The opening section points towards an Isabelle Huppertish novel about an impending sense of menace - the shy character taking the neutral-seeming interpreter job who finds herself drawn unconsciously into identifying with the war criminals she translates for, into living in dangerous neighborhoods, into an ever-more fraught affair with a married man. But the narrative tension of this plot line dissipates quickly - the married man leaves the country, the trial of the war criminal breaks down into extended tedium - and the novel seems to take on a different trajectory, as the portrait of a society experiencing a slow burn: all the minutely-described meetings, all the visits to still life exhibitions, which are meant through a certain sort of woke logic to stand in for a society that’s hiding from its own propensity to violence and that will sooner or later be overwhelmed by the demons of its past. And then Kitamura seems to realize that she’s made her point - and made it very overtly with the anti-colonial speech that the war criminal defendant makes unprompted to the narrator - and the novel switches gears one final time and hints at the challenges of identification, the translator as a peculiarly chameleonic figure who can speak at once for victim and perpetrator, who has no clear identity within the matrix of power, but, as the narrator observes to the defendant, “bridges gaps between language.”

Any one of these seems to be an intriguing novel - and I found myself excited about each one of them, with Kitamura like a card player announcing trumps for a hand that she never ends up playing. What preoccupies Kitamura instead is oddly miniaturist embroidering, not-particularly-consequential scenes in which every look is charted out as if we were in a silent movie. Here is how Kitamura describes a dinner party that lapses into uncomfortable silence over a discussion of a neighborhood burglary: “Perhaps a full minute later, she looked up and smiled. What a depressing turn to the conversation, that’s my fault. She reached for the bottle of wine and poured herself another glass, and then filled both my glass and Adriaan’s. I shook my head and said, It’s only natural to worry, or words to that effect, words without any particular meaning. The subject had seemed so innocuous, mere small talk - and yet it had cordoned each of us into a private realm, it as if we had mutually agreed there was no more to be said between us.”

And there are various ways to justify this - that we are in the head of a character who is very shy and perceptive and that these stray, scrutinized moments have more import for her than any of the ostensibly major plot points; that there’s a feminist case being made about the emotionally-charged minutiae that actually can change the course of a person’s life (the overarching narrative of Intimacies in a sense has nothing to do with the trial or with the relationship with Adriaan but is all a temperature check for the narrator about whether she wants to live in the Netherlands/The Hague). But none of the justifications quite hold up. The mania for miniaturist, lifelike detail is offset by truly melodramatic coincidences - any time the narrator meets some apparently secondary character, a man hitting on her at a party, the brother of a friend, it’s a cinch that she’ll bump into them a few pages later on and have the opportunity to observe them perfectly unobserved. And the scenes that receive so much attention never seem to go anywhere - excruciating detail is lacquered onto the interaction between the narrator’s friend Jana and the narrator’s boyfriend Adriaan, which could potentially be a haunting scene, the narrator oversleeping a meeting and, by the time she arrives, finding herself third wheeling at the flirtation of two people who are clearly going to end up together, except that, as tends to happen in Intimacies, Jana and Adriaan never see each other again.

The narrative seems constantly to collapse into these eddies of confusion, and what we’re left with in the end is the narrator’s shyness, her overpowering passivity. That passivity, accompanied naturally by self-loathing, turns out to be the dominant force in the novel. She finds herself staying in The Hague because of a man and is upset with herself for doing so: “Adriaan was the reason why I wanted to stay in The Hague, though I was embarrassed to admit this even to myself - I did not like to think of myself as a woman who made decisions in this way, for a man.” Trying to find a cultural justification for being there she seems to latch onto the underwhelming idea that “the Dutch are neutral” before remembering that, unfortunately, they are not always and even neutrality has a kind of aggression to it. And subjected to a tongue-lashing from the war criminal ex-president, who lambasts her for being Western, she declines to stand up for herself, mildly telling another interpreter, incensed on her behalf, that “He didn’t say anything that wasn’t true.” It is possible that this is meant to be the totalizing effect of Intimacies - the image of a culture collapsing into guilt and passivity, as embodied by a protagonist who is enthralled by violence and by men of action but is incapable of even saying a word in her own defense - but, if so, the image turns out to be cartoonish, and the narrator’s passivity so over the top and so peculiar that it seems not to stand for anything at all.

I’m left scratching my head a bit about the failure or, really, the forfeit of Intimacies. Kitamura gives the impression of being a skilled writer and there’s a strong sense of rhythm throughout the novel. My guess is that Kitamura has been afflicted by what I’ve come to think of as the curse of Rachel Cusk - at the moment the reigning curse in literature. A studious minimalism is practiced - the novel becomes a kind of day planner of the more or less trivial events that a character goes through over the normal course of their lives, with a bet made that the accumulation of those details will create a peculiar power and sense of sanctity. I don’t really think it works for Cusk, although I’m in the minority there - but it definitely doesn’t work for Cusk’s followers, for writers like Lauren Oyler, Lisa Halliday, and Kitamura. Oyler’s Fake Accounts is very similar to Intimacies as a kind of case study of what can go wrong with this approach - the writer seems never to make up her mind about the scale she’s working in, whether the events described are significant or are so trivial that their triviality itself gives them a certain splendor. The usual result is to make mountains out of molehills - that’s definitely the case in Fake Accounts and it is as well in Intimacies, all the cringing scenes, with their oddly fusty morality, in which Kitamura’s narrator is deeply worried, for instance, about whether her cab driver will think her skirt is too short or her endless prurient speculation about what Anton, Jana’s brother, was really doing in the dangerous neighborhood at night.

Kitamura to her credit is aware of the ambivalence and paralysis in her narrative perspective. Sometimes this manifests as frustration with the slow pace of things in the story - it’s almost never a good sign in a novel, by the way, when the writer starts to complain about their own tediousness. But it materializes also in a very evocative moment. The narrator looks at a painting by Judith Leyster and is startled at the complexity of it:“The painting operated around a schism, it represented two irreconcilable subjective positions: the man, who believed the scene to be one of ardor and seduction, and the woman, who had been plunged into a state of fear and humiliation.” Here, Kitamura seems to get close to what she really wants to say - that the same moment can have many different meanings, that in a given interaction one interlocutor may be relaxed and insouciant and the other deeply agitated. That’s not bad as an encapsulation of the critical dynamics of the MeToo era - all the interactions that seem to admit of such wildly different interpretations - and it’s sort of the organizing principle of Intimacies, the character who is a little more sensitive than everybody around her and as a result is affected by apparently ordinary events in ways that everyone else is not. So - fair enough. As happened to me multiple times while I was reading Intimacies, there were moments when I talked myself into liking it. But not completely convincingly. My belief is that for a novel to really work, a writer needs to have some idea of what they want to say and needs to be guided by an internal strength. Maybe intriguingly, Kitamura is experimenting with the opposite - a novel that drifts and is inchoate and animated by weakness. I could imagine somebody making the case that that’s innovative and true to our time, but, deep down, that’s just not what I want literature to be.

TOM O’NEILL’s Chaos: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties (2019)

I had a terrible couple of days recently and it turned out that Chaos was the only possible company - really didn’t want to think about my own life and found that the best escapism was disappearance down all the various rabbit holes that O’Neill pursues. I’ve used this strategy to get through difficult days before - although the challenge is that ’60s ‘conspiracy theories’ aren’t really escapist at all, they develop into a very strange, and strangely satisfying form of misanthropy, the feeling that nothing is real, that everything taken to be ‘authoritative’ is a lie.

Because - start scratching at the surface and actually sifting through evidence, as O’Neill has been doing for twenty years - and it turns out that the oddest, most ‘conspiracy’-ish theories are actually, often, completely true, and documented, and the official version falls away into just some sort of convenient fiction. It’s not at all easy to parse that sort of conclusion from Chaos because O’Neill is so careful, keeps returning compulsively to aspects of the official narrative again and again as a reality-check on himself, to see if he’s completely crazy - and has to keep reminding himself that, no, the evidence he’s turned up is incontrovertible and some new narrative is needed to fit all the elements of the Manson case.

And, unfortunately, out of an abundance of caution, O’Neill refrains from doing that - although he clearly, at this stage, knows more about the Manson case than anybody alive - so I’d like to see if I can kind of piece it together from where O’Neill leaves off, which involves basically restating the book in backwards order, starting from O’Neill’s leading findings.

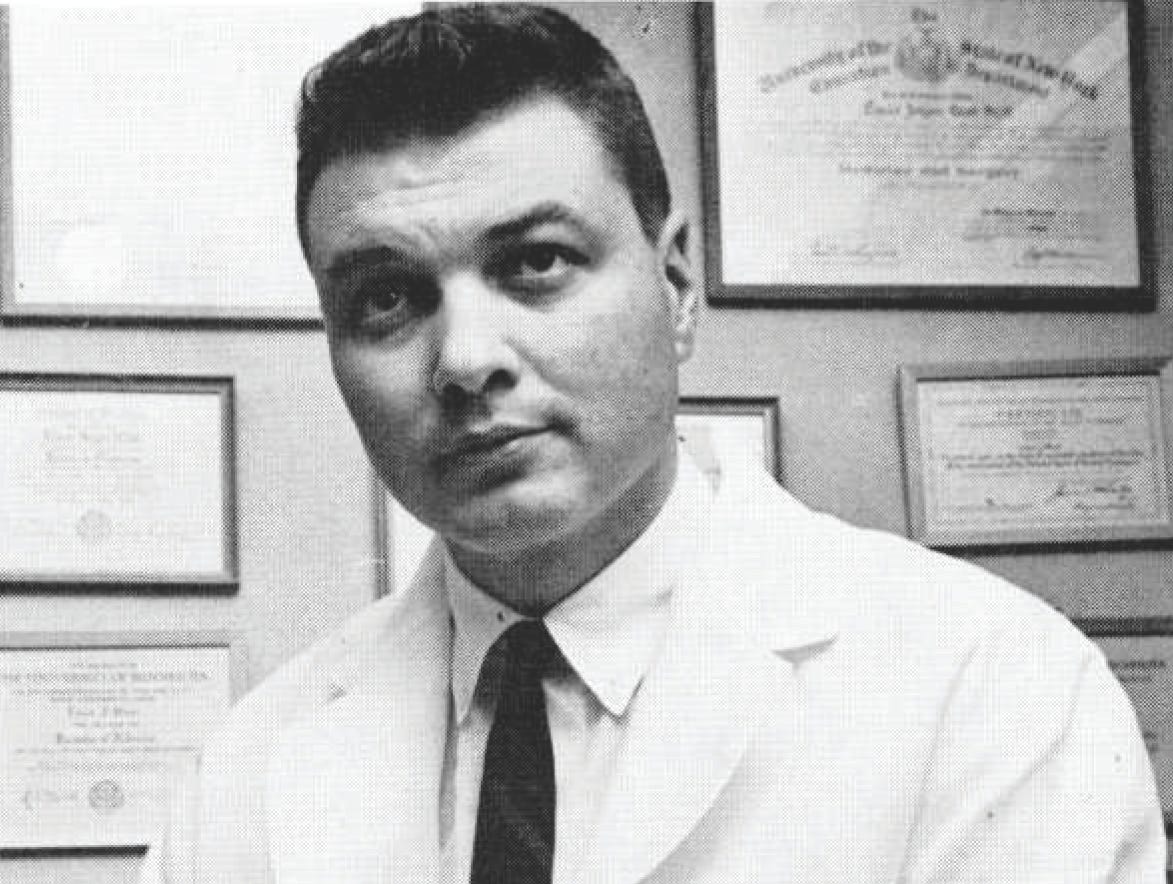

His real coup may, it turns out, be only glancingly related to Manson - which is proof that the psychiatrist Jolly West absolutely was part of MKUltra, with a direct line to Sidney Gottlieb and heavy involvement in many of the leading cases of the era. West was working on a project for reprogramming memories, replacing true memories with fiction, and believed that he had actually accomplished it through a combination of LSD and hypnosis. That project dovetails perfectly with the aims of the CIA from the Korean War era onwards - to exercise mind control and to create perfectly-programmed assassins with perfectly plausible deniability. That technology seems to have been deployed as early as 1954 in the deeply creepy Shaver case in which an airman at an base where West worked as a psychiatrist was accused of brutally murdering a three-year-old and had no memory of having done so until West, acting as court-appointed psychiatrist, succeeded, through a combination of sodium pentothol and hypnosis, in restoring the memory. A variant of West’s skills with this technique manifested in his interview of Jack Ruby in prison in the spring of 1964 - and, after an extended unmonitored visit from West, Ruby had what West described as an ‘acute psychotic break,’ which West further described as irrevocable and which rendered Ruby useless as a witness for the Warren Commission from that point forward. In 1968, West surfaced in the Haight-Ashbury, running a house to study hippies and with an office at the famous Haight-Ashbury Free Medical Clinic, which was also frequented by Manson.

At this point, when he’s so agonizingly close, O’Neill loses the connection between his two main threads - West and Manson. There’s no record of their meeting let alone of West’s having in some way ‘run’ him, but for the sake of O’Neill’s larger thesis he doesn’t actually have to prove that. The circumstantial evidence is overwhelming that Manson was tied in with the ‘San Francisco Project,’ which ran largely through the Clinic and that he was exactly the sort of experiment that West and his CIA cohort were looking to conduct.

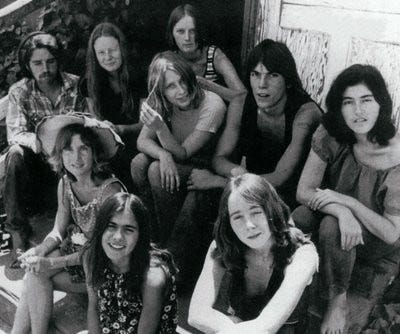

That experiment appears to run in two directions. On the one hand, Manson demonstrates in humans a proposition that the Clinic’s cohort were actively testing in rats and mice - that certain kinds of stimulation could create a pack frenzy by which affected subjects would tear apart one another or a chosen victim. On the other, Manson would serve to discredit LSD and the leftist counterculture - which appears to have been the overriding aim of West’s programme in San Francisco.

That dual set of interests yields almost too neat of a resolution. As an interlocutor of O’Neill’s exclaims when O’Neill calls Manson an MKUltra experiment gone wrong: “No, it’s an MKUltra experiment gone right.” In that construction, the CIA was able through Manson to conduct an experiment proving the efficacy of LSD plus hypnosis and possibly speed in achieving mind control as well as generating violence - and then the Tate-LaBianca murders served almost single-handedly to bring to an end the ‘flower power’ moment of the ’60s, ‘proving’ that left-wing radicalism was anything but benign and that LSD was intrinsically a violent drug.

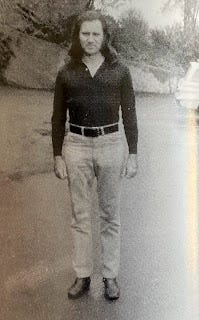

That dual-pronged conceit is O’Neill’s real thesis and parts of it he is able to prove with startling accuracy while other aspects of it remain - almost certainly - permanently unknowable. He is able to prove the research interest of West, Roger Smith, and Dave Smith in inducing violent states in mice and rats through the administration of LSD and hypnosis; able to prove the abnormal interest that Roger Smith took in Manson in his role as Manson’s parole officer, watching Manson develop the Family right under his nose and helping out Manson any time he got into trouble; able to prove a pattern of catch-and-release for Manson in the period 1967-69 when, with Smith’s assistance, he had a virtual ‘get out of jail free card’ for offenses that, with any normal con, would certainly, at a minimum, have resulted in the revocation of his parole.

Where things start to get a bit difficult for O’Neill’s structure is the murky chain of events leading to the Manson Family’s murders. Several different motives are posited for the killings, none of them any more convincing than the others. A certain amount of circumstantial evidence accrues around the possibility of a drug deal gone wrong - the idea that Manson was heavily tied in with a group of shady ex-military types hanging around 10050 Cielo Drive and that the murders were revenge. More direct evidence indicates that the 10050 Cielo Drive murders were an attempt to free Family member Bobby Beausoleil who had just been arrested for the murder of Gary Hinman - and O’Neill is deeply convincing in showing how police departments buried evidence that would support that explanation. Another set of evidence would seem to point towards the theme of discrediting the left - with Manson attempting to pin the murders on the Black Panthers. Within all of this swirling and criss-crossing information, Vincent Bugliosi’s Helter Skelter theory seems no more or less plausible than the others - the idea being that Manson was looking to instigate the great race war and decided that, in its kickoff, he would kill two birds with one stone, striking at the house of Terry Melcher who had reneged on a record deal. O’Neill is heavily focused on discrediting the Helter Skelter theory, and he does poke significant holes in its logic, above all by demonstrating that Terry Melcher visited the Manson Family three times after the Tate-LaBianca killings, which, he claims, would seem not to be the behavior of somebody who had had terror struck into him by Tate-LaBianca, as the Helter Skelter theory would indicate. But it’s very difficult to know what to make of Melcher’s three visits. Notes about them describe him sinking to his knees and begging Manson’s forgiveness for offenses unspecified - which seems not at all out of character for somebody in mortal terror. In any case, O’Neill more or less leaves the Melcher thread alone after his initial revelation - and, as far as I can tell, the Melcher thread has nothing to do with the heart of O’Neill’s findings, which are about CIA mind control and the connivance of law enforcement in CIA domestic programs.

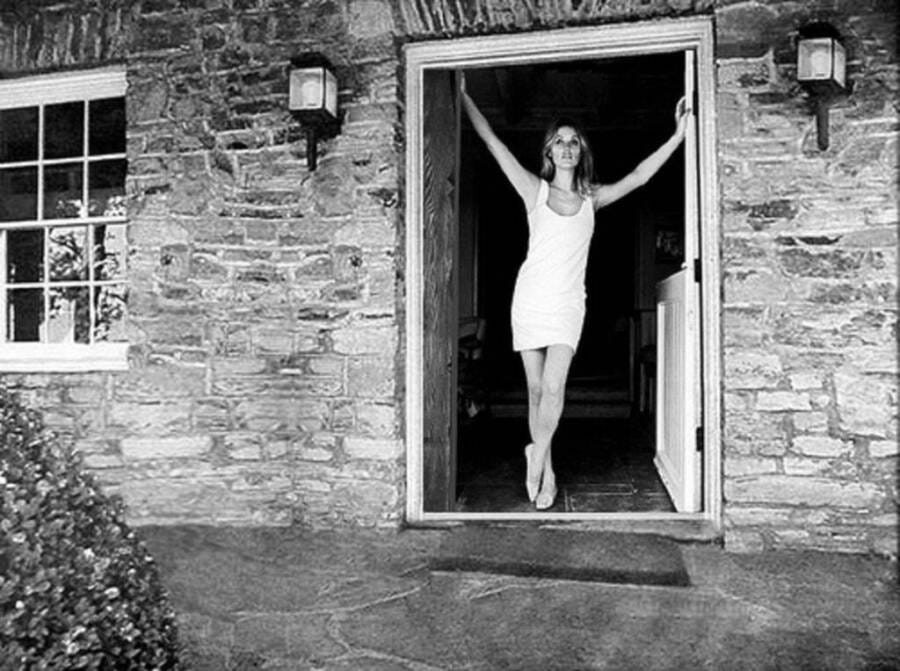

That thread returns in the really stunning tale of Reeve Whitson, a marginal figure in most accounts of the case and who, in O’Neill’s telling, becomes, really, the central character. Whitson, as O’Neill notes, comes across like a figure out of a “not terribly well written spy novel” - but O’Neill, through dogged research, produces all kinds of evidence, notably interviews with his wife and daughter, to indicate that Whitson really was a CIA agent operating in Los Angeles, that he was from an ultra secret branch of the CIA virtually unknown even within the Agency (Whitson himself referred to it as ‘the Quarry’) and that he was all over the Manson case both in the lead-up and the investigation. O’Neill places Whitson at 10050 Cielo Drive in advance of the murders; connects him with the ‘Golden Penetrators,’ including Melcher, who were far more deeply involved with Manson than they admitted at the time of the trial; demonstrates that he called a critical witness with news of the murders hours before the police came across the crime scene; places him per Sharon Tate’s Army Colonel father in a critical role in the investigation, “always one step ahead of the other investigators”; and, most startlingly, makes the claim that Whitson may well have returned with Manson to Cielo Drive the night of the murders and rearranged the bodies. O’Neill doesn’t quite clinch the last claim but is more than persuasive on the others. The inference - although O’Neill would chafe at this sort of simplistic phrasing - is that Whitson was essentially Manson’s CIA handler in Los Angeles, much as Roger Smith had been his handler upstate. O’Neill doesn’t attempt to demonstrate a handoff between CIA agents but there is a clear sense of shared m.o. - a view that Manson was valuable and that there was a need to intercede with local law enforcement for the sake of higher interests. If the whole thing feels implausible - CIA agents moving bodies around in the wake of a mass murder - it actually does seem to be in keeping with a certain practiced amorality which was in the spirit of the CIA in that time, a sense that, as an acquaintance says of Whitson, “He didn’t believe in the individual but in the larger picture.” It is not at all difficult to infer a viable motive to West, Whitson, etc - which is that they really believed the counterculture represented an existential threat to America. The willingness of law enforcement and intelligence types to subordinate all normal ethical considerations to this ‘higher’ patriotic motive is completely typical of the period - and runs through all the available documentation on MKUltra.

But if the CIA really did have this kind of hands-on involvement with the Tate-LaBianca murders as in the Whitson scenario, then there are a couple of major issues that O’Neill, unfortunately, doesn’t address. One is why the State would - after having at last apprehended Manson - be willing to seek the death penalty for Manson and go to great lengths to do so even knowing that he was a government asset. The other is why Manson, cornered, wouldn’t then flip on his CIA handlers. I sort of know the explanation for the first objection - that the CIA’s mind control wing really treated its subjects entirely as lab rats, to the extent that West went along with the death penalty conviction of Jimmy Shaver in 1958, no matter that West may well have himself programmed Shaver to commit the crime (West did, for the rest of his life, become a vociferous opponent of the death penalty). And the same may well have been true of the CIA’s approach to the Family, which, depending on interpretation, had either lurched away from its intended purpose or had fulfilled it and was no longer necessary. But that doesn’t solve the second objection, which is why Manson and the Family would have said nothing about Whitson or Roger Smith if they really had been so involved in his handling. And, here, O’Neill’s failure to secure even a single interview with a Family member looms large. I don’t quite know what to make of this. Apparently, O’Neill tried very hard to interview Family members and had some slight success with Manson himself. But the Family shut him down, mostly because they were tired of journalists, and so O’Neill’s bombshell claims go uncorroborated by the people who would have been best positioned to speak for them.

The interviews he does garner are all somehow underwhelming. Bugliosi, Roger and Dave Smith, Terry Melcher, are all willing to speak to him for some period of time. Their rage at O’Neill’s line of questioning would seem to implicate them, but most of them keep it surprisingly together - the Smiths yield virtually nothing at all and clearly compel O’Neill to consider the possibility that he’s a crank and his interlocutors were, after all, just doing their jobs.

But if O’Neill’s inability to decisively crack the case brings him into a defensive posture - claiming that he is “not…offering hypotheses…merely questioning the established narrative” - that does not invalidate the conspiracy-ish leads he uncovers. ‘The Secret History of the Sixties’ is a fitting subtitle for the book and it’s good on Little Brown that they allowed it to be appended. Manson, in a curious way, turns out to be the weakest link in O’Neill’s case. He was so sociopathic and unpredictable that any attempt to ascribe motive to him founders on the sheer irrationality of everything about him. But the CIA agents and law enforcement figures strung out across California were rational and much of their behavior is completely inexplicable according to the accepted narrative of events and perfectly reasonable if they understood Manson to be a prized asset of some high-level federal entity.

It is astonishing, in that respect, to read the reviews of Chaos and to realize how much mainstream media, even now, is in thrall to narratives that depict a binary between official, authoritative versions of events and ‘conspiracy.’ Bookforum calls Chaos a “conspiracy-laden account of the Manson murders.” The Sunday Times claims that “the wheels start to come off when O’Neill begins searching for alternative explanations” and that “all O’Neill can manage [on the CIA] is wild speculation.” The New York Times, by the way, declined even to review the book. All of which really makes me upset to read. O’Neill dedicated twenty years to Chaos. He passed up abundant opportunities to bail out into a tidier book or magazine piece both because he believed in the story and, more importantly, because he believed in the documentation, that if he dug enough he could produce irrefutable evidence that he was at the very least on the right track - and the reaction of a large number of reviewers is to skim the book and, in the face of all of O’Neill’s copious evidence, call the second half ‘conspiracy-laden.’ Which makes one wonder that they think the CIA was up to all through the ’60s and ’70s, if was essentially some sort of benign intelligence-gathering shop, if the revelations of the Church Committee, House Select Committee on Assassinations, etc, were all just conspiracy talk. The great value of a book like Chaos - like Scorpions’ Dance or Wormwood - is that it compels anybody who pays attention to treat the ‘official’ narrative as just another kind of fiction with no greater claim to accuracy than anything that the obsessive ‘fringe’ may have come up with. The canvas gets wiped clean. A narrative like Helter Skelter, just because it sold millions of copies or was written by a D.A., is no longer seen as anything more than the vested interest of a particular figure with a great deal both to gain and lose from the Manson case. Truth turns out to be a highly elusive commodity, but a really diligent researcher like O’Neill is able to piece together enough evidence to point unequivocally in a particular direction. And at a certain point ‘common sense’ does need to shift - there really does have to be an understanding that much of what was seen to be paranoiac raving about the CIA actually was true, that the CIA operated highly sociopathic programs on American soil (e.g. MKUltra) for the purposes both of experimenting with mind control and of discrediting the countercultural left. The preponderance of the evidence, per O’Neill, indicates that Manson was an asset connected to just such a program - and the CIA’s willingness to condone such egregious violence forces us to revisit the history of the late ’60s from a different vantage-point (which was, all along, the perspective of the radical left) and to recognize the extent to which the CIA and high-level government entities since then have poisoned the narrative.

So compelling a read that, when you have a couple of bad days, we lucky subscribers get insights into the motives of reviewers and publishers, let alone the CIA--and the two books you review here. I've not read either of these books. But I have read Outline, Transit, Kudos and Coventry by Rachel Cusk. Clearly, I was somewhat compelled by her but have mixed feelings because of what I would call "a certain and purposeful narrative distance" from what is clearly autobiographical-fiction--with the exception of the essays in Coventry. But maybe that narrative distance and minimalism are her gift? Not something I can do, for sure. Is that what you're implying about Cusk--or am I missing your point? In any case, this essay, a great read! xo Mary

Hi, 1st timer visitor here; a very astute review; next time you are “in the mood” try Revolution’s End by Brad Schreiber. It’s a nice sequel to Chaos