COLSON WHITEHEAD’s Harlem Shuffle (2021)

A rollicking, enthralling, high-class novel - for the first 100 pages. I don’t exactly know what went wrong here - it may be as simple as Whitehead’s having set aside a manuscript and come back to it too late - but Harlem Shuffle reads as three wildly disparate books stitched together with the author barely able to remember what had happened in the early pages and certainly incapable of regaining their magic.

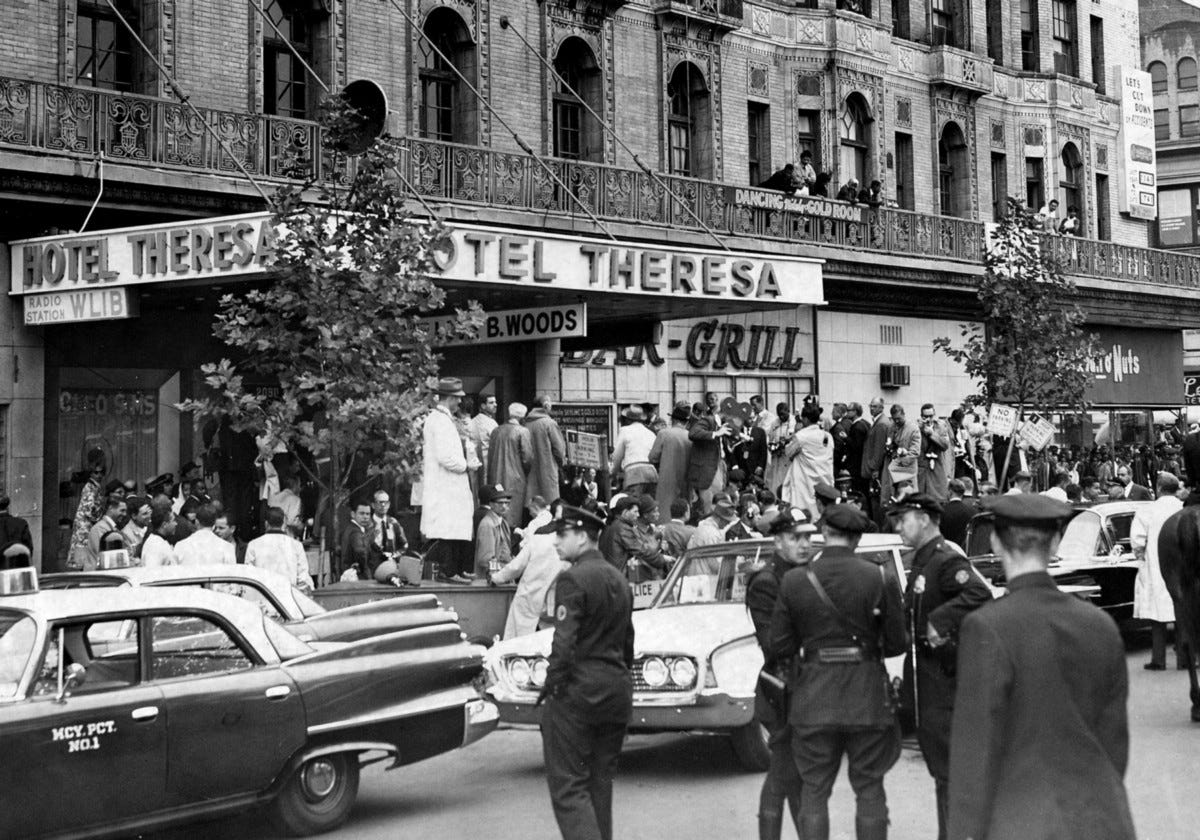

I read Part One - the story of the Hotel Theresa stickup - completely captivated. The sense is of a richly textured novel clicking on at least three different levels. In sentence-to-sentence prose, Whitehead writes like a master, striking a balance between criminal argot and a discreetly poetic lyricism. It’s hard to resist a sentence, describing stick-up technique, like “One school held that the base of the skull was the best spot, the cool metal initiating a physical reaction of fear, but the Miami school of which Joe was a disciple liked below the ear,” which is perfectly immersed in the logic of its milieu. Or a sentence like “Miami Joe sipped Canadian club and twisted his pinkie rings as he mined the dark rock of his thoughts,” which is equally hard but has an elegant turn to it - a sense of the grandeur of the gangster culture, a Godfather-ish feeling of a whole way of life, with its airtight codes of conduct, just on the verge of passing into the realm of legend. And not only that but Whitehead has hit on the sort of platonic ideal for telling the story of a caper - viewing everything from the perspective of the fence, who is neatly balanced between the straight world and the crooked and who will be the most vulnerable once the caper falls apart and everybody turns on each other. And not only that but Whitehead is perfectly set up for an overarching historical narrative in which the middle class black shopkeeper is slowly squeezed out of business and a briefly promising moment in Harlem is ground down from a combination of heroin, crime, and iron-fisted economics.

It seems like a can’t-miss kind of story with an in-built narrative trajectory - Carney finding himself drawn deeper into the crossfire between Miami Joe and Chick Montague’s gangs while having to contend with police extortion and while desperately trying to keep his in-laws from discovering the extent of his criminality. And then, for reasons completely unknown, Whitehead kills off Miami Joe, his best character, at the end of the first part. Pepper, his second best character, disappears for the heart of the novel. And Whitehead tells a dull, meandering, and implausible story of Carney trying to get revenge on a banker who freezes him out of membership to a social club. I think I can understand what Whitehead hoped to do: instead of sticking with his original cast members, he would follow Carney as he climbed up the social ladder, first dealing with the Harlem social club and then dealing eventually with whitey himself while perpetually held back by his cousin Freddie and the spirit of Mike Carney. But this motif has the feeling of a video game in its crank-out-the-sequels phase, always confronting a higher-stakes, more glamorous antagonist, and oblivious to the escalating absurdity of the outline.

There are difficulties to be spotted early on. There’s something very diorama-ish about Carney’s inner life. Even in the excellent first section we keep getting reminded more than we should that he would really like to live on Riverside Drive, that his in-laws look down on him, that his father was a charismatic hoodlum and Freddie a sweet kid, that he is constantly between a rock and a hard place in his business dealings. By the second section, Whitehead seems to have forgotten that he has already given us all this information. Perfectly well-described scenes from the early chapters are limply recapped. And Carney’s inner life, always something of a pass-through for impressions of other characters, increasingly transposes itself over into the kind of copy you’d expect on a museum placard. “All across the country one observed signs of racial progress; perhaps the home furnishing industry kept pace with the changing times” is apparently Carney’s actual thought. Or: “He wondered how many black boys Munson and his cronies had worked over and then tossed into the backseat on the way to the station house.” Worse than that, Whitehead utterly loses the rhythmic music he had in the novel’s first section. Suddenly cops speak like the following: “We’re investigating a death that occurred last night uptown. A deceased person” or - and it embarrasses me to even copy this out - “Take a gander at my Fucking Apology Face - it’s like Medusa, you only ever see it once.” And the narration starts to turn into a children’s book’s version of the story of the honorable fence and his hoodlum friend.

By the time we get to the villain of villains - Van Wyck of the Van Wyck expressway - we are really in a very rudimentary moral universe. Whites have “smug yacht-club grins.” Rich whites named Ambrose beat their sons with loafers for saying ‘Can I?’ not ‘May I?’ and respond to violent break-ins by saying “I’m too tired to deal with your foolishness.”

As you can see, it’s really just a joke - like jaw-hanging-down terrible writing. The feeling is a bit of the sort of tapped phone call where you have to speak carefully only as long as law enforcement is listening in - and it’s as if Whitehead writes with care just long enough for the reviewers and blurb writers to gather their material before he completely slacks off. But my hypothesis for what might have gone so terribly wrong here is more than just about a writer phoning it in or losing the thread. Whitehead started to write Harlem Shuffle in the mid-2010s. By the time he picked it back up in 2020 the literary landscape had changed. Subtlety was now in bad taste. Everything was written as if in crayon - as crude and as unmissable as possible. (And this extended to the sentence-by-sentence composition, Whitehead uncorking a gem like “[Freddie’s] partiality for Debbie Reynolds was durable and verified,” which was a very epic way of writing that ‘Freddie liked Debbie Reynolds.’) The sole viable storyline was the catalog of unremitting oppression - which could be relieved only through some sort of cathartic world-shifting act of violence, in this case, the assassination of a group of haughty, high-boned whites in a conference room.

Also, by this stage, Whitehead was so well established that he may have figured he could get away with anything. But Whitehead is a skilled, serious writer and, even when phoning it in, should be able to do better than this. The really shocking decline of Harlem Shuffle starts to feel like one of these archeological artifacts where you’re able to detect cultural faultlines within the retouches of a single work of art. I don’t think Whitehead wrote the ending of Harlem Shuffle so crudely because he’s a bad writer. I think he wrote it that way because he felt that that’s how he was supposed to write.

MALCOLM GLADWELL’s The Bomber Mafia (2021)

I’ve had it with Malcolm Gladwell for a while and this book confirms it. And what’s most interesting about The Bomber Mafia is that Gladwell seems to be getting tired of himself and of his shtick as well – or, at least, the logical trajectory of The Bomber Mafia is a repudiation of the mentality that he has dedicated his career to.

The Bomber Mafia looks and feels like classic Gladwell – although with his usual New York Times Bestseller-ready prose translated into baby-talk for the podcast crowd. There are the scrappy outsiders with their counter-intuitive, data-driven theory who are on the verge of changing everything. In this case, the scrappy outsiders are a group of independent-minded bombing strategists at Maxwell Field in the 1920s and ’30s and their Gladwellian project is to reshape the landscape of war by bombing with such precision that they can incapacitate an enemy’s entire infrastructure with a few well-aimed blows and bring wars to quick and humanitarian ends. In Gladwellian logic, we are of course fully on the side of these ragtag misfits – the hyper-focused Dutch scientist who developed the bombsight, resolving “one of the ten biggest unsolved technological problems of the [inter-war era]” but was also charmingly curt with subordinates, thought Franklin Roosevelt was the devil, and kept unnerving his American handlers by traveling to Switzerland within easy range of the Abwehr; the Air Force General Haywood Hansell who quoted poetry and was fond of Gilbert and Sullivan; even the architect who designed the Air Force’s glamorously futuristic chapel. As iconoclastic misfits, they check all the boxes – they are tough (they are in the business of industrialized war, after all) but, beyond that, they are data-driven, capable of thinking originally, and dedicated to a utilitarian best-fit solution, which, in their case, is the most wonderfully utilitarian idea of all, high-tech war that spares civilians and eliminates the need for large armies.

But there’s a twist, glossed over for much of the narrative, which is that the vision of the ‘Bomber Mafia’ didn’t work. The super-high-tech Norden bombsight was impractical for bombardiers attempting to hit targets while in the midst of aerial dogfights. The U.S.’ policy of daytime raids in Europe meant higher casualties for the bombers and with very little evidentiary proof that their strikes affected the German war effort. And, in the Pacific, under the guidance of Hansell, the U.S.’ air campaign ground nearly to a halt – the jet stream effectively incapacitating the Norden bombsight. And the solution turns out to be – brutal and wide-ranging bombing of civilian populations. The natural enemies of the Bomber Mafia are a crew of inveterate sociopaths – the British Air Marshal Harris and the Churchill advisor Frederic Lindemann and, on the American side, Curtis LeMay. In Europe, the logic of battle shifts towards the British approach – a disastrous raid on a ball-bearing factory deep inside Germany leads, essentially, to the abandonment of daylight precision bombing – while, in the Pacific, courtly Haywood Hansell is ushered out in favor of LeMay and a decidedly unsubtle bombing strategy of coming in low, regardless of weather, and striking cities with the idea of obliterating them.

Gladwell is right about one thing, which is his choice of subject matter. The question of effective bombing strategy during World War II is, at heart, a philosophical conundrum – and it impacts everything. Gladwell’s best line in The Bomber Mafia is to write, “Give Napoleon one week of training and he probably could have managed the Allied push across Europe. But the Pacific theater? It was on the other end of the war-absurdity continuum….You could do this, as an American Army officer, if you wanted: you could take out entire cities. And then more. One after another.” The idea – which isn’t unique with Gladwell but bears repeating – is that the strategic bombing campaigns unleashed a certain kind of evil in the world, with attendant moral calculuses, and that, to a great extent, our entire geopolitics is still frozen in 1945, with the understanding that the old logic of war, with the steady escalation of modes of force, the use of all available weaponry, the urge to seek a quick resolution, is no longer morally defensible – that it would lead, in short order, to the destruction of all life on the planet. And the ability to continue fighting wars – which will of course happen – hinges on a certain ingenuity, an ability to gain tactical superiority without blithely annihilating civilian populations. The Bomber Mafia guys would seem to have been ahead of the curve on that – they were thinking about these questions as early as the 1920s and, on the blackboard at least, had an intelligent solution of pinpointing crucial components of the war-making machinery.

However, almost nothing else in Gladwell’s narrative develops along the prefabricated lines of the Gladwell Thesis. At the critical moment, the Bomber Mafia strategy turns out to be inept and self-destructive without exactly winning points for humanitarian forbearance – and, in short order, brute force prevails. As Gladwell coquettishly admits, “People are fascinated by LeMay….ok, I’m fascinated by LeMay.” And the real reason – I suspect – is that Gladwell’s whole worldview has a way of collapsing into LeMay-style brutality. His formulation of problems tends to be elegant and intellectual – why is that so many professional Canadian hockey players have their birthdays in the first months of the year, why is it that Paul Revere’s ride was so much more significant than the ride of William Dawes, who followed pretty much the exact same route on the exact same night – but the solutions are always brutal and data-driven e.g. Canadian hockey players with birthdays early in the year hit puberty earlier than their counterparts and therefore received more institutional resources, which gave them an advantage for the rest of their careers; Revere simply knew more people than Dawes and his ride led to the formation of a militia. The neat formulation of the Bomber Mafia – how do we wage a high-tech strategic bombing campaign with minimal civilian casualties – shifts ever so easily into a different formulation of the same problem, how do we end a war as quickly as possible, and which admits of a very simple, data-driven, brutally-logical solution of, as LeMay allegedly put it, bombing the enemy “back into the Stone Age.”

Looking back on the decade and a half in which Gladwell has been very nearly America’s premier intellectual – I suspect he’s been more influential than anybody else – that, above all, seems to be his legacy, the logic of saturation, of throwing data at the problem. That was the logic of the Hillary campaign – the cannot-lose data metrics that were spun out all through the fall of 2016 and paid no attention to the mood of the country – and it’s the logic of a sledgehammer approach to creativity, the belief that all human endeavors are readily translated into quantifiable activities, and creative excellence turns out to be a function, simply, of the hours put into achieving mastery. And the result of all of that is dataism – a deep disregarding of human intuition, a belief that, whatever the spreadsheet or the computer printout shows, however counter-intuitive it may be, has to be the truth. That philosophy, of course, fit hand-in-glove with the profit motive of the tech mandarins – but, as The Bomber Mafia inadvertently shows, it can be deployed for even more sinister purposes, as in the straightforward cause-and-effect logic of Curtis LeMay with its utilitarian underpinnings. The goal is to end the war as fast as possible? LeMay sneers back to the Air Force eggheads. Well, I’ll show you the fastest and most effective method of all.

At various moments in The Bomber Mafia Gladwell seems to sense that the book is getting away from him – in his admission of his fascination with LeMay, in the paltry evidence he produces of the effectiveness of the Bomber Mafia’s strategy (a single entry in the memoir of Albert Speer claiming that the United States gave up too quickly in its attack on German ball-bearing production). That is never more apparent than in a dazzling sleight-of-hand at the very end of The Bomber Mafia in which Gladwell writes, “Curtis LeMay won the battle. Haywood Hansell won the war.” What he means, I think, is that United States military strategy has, especially in recent decades, shifted towards precision strikes – as in the targeting of leading terrorists, the civilian-casualty-reduction-strategy of drone warfare, etc. But this snatching of victory from deep, deep in the jaws of defeat is in bad faith – and Gladwell, I suspect, is not at all fooled by his own last line. War has remained a deeply violent business encompassing countless civilian casualties. Precise targeting of enemy assets hit its high-water mark in the destruction of the Death Star in Star Wars; in the real world of war, high-value targets tend to be dispersed or moved around or hidden behind civilian human shields and engineers of the real-world Death Stars tend not to make their weapons vulnerable to obliteration from a single well-aimed shot. And a cutely articulated compromise like Gladwell’s – have the terrible weapons but deploy them only in brilliant ways and only in ways that eliminate civilian casualties – runs the risk always of a certain intellectual smugness and naïveté, and then, in the moment of truth, the weapons end up being co-opted inevitably by figures like LeMay.

Two terrible books. Review books that are worth the time please and thank you.

Sweet!