Dear Friends,

I’m sharing a pair of book reviews/discussions — one fiction, one non-fiction.

Best,

Sam

EMMA CLINE’s The Guest (2023)

To me, Emma Cline is a very hopeful indication that, in spite of everything, the publishing industry is actually in a good place and the literary market knows what it’s doing. Cline is an enormous talent and she was instantly recognized as such — auctioning her first novel for $2 million. As far as I’m concerned, she’s worth every penny. She has the spiky, let’s-look-inside-the-medicine-cabinet intelligence of so many precocious female writers (I’m thinking of Sally Rooney, Lena Dunham, Françoise Sagan) and her prose is like a miracle of third-person limited narration, packing whole worldviews into crisp, apparently straightforward short sentences.

Reading The Guest, I found myself copying out line after line of prose, most of it Alex’s highly-attuned analyses of intricate social dynamics.

“Alex spent hours being chased from room to room by silent, industrious Patricia, who took in Alex’s presence with the same moving expression she took in any mess.”

“Everyone said it was beautiful out here. How many times could this sentiment be repeated? It was the polite consensus to return to, the bookend to every conversation — a slogan that united everyone in their shared luck.”

“People, it turned out, were mostly fine with being victimized in small doses. In fact, they seemed to expect a certain amount of deception, allowed for a tolerable margin of manipulation in their relationships.”

“He took her in with a bemused air. Like someone watching a movie they’d already seen.”

The plot of The Guest is sort of optimized for Cline to show off her abilities. The novel’s world is all social dynamics, pure neo-Gilded Age in which wealth and class categories are entirely fixed, in which behavior is like some sort of logarithmic function of one’s precise socioeconomic status, and in which Alex almost alone of anyone in the world surrounding her has the ability to swerve between classes, to apprehend what’s around her. In The Guest, status is almost exactly inversely proportional to perception. Those who are downstairs — the housekeepers, bartenders, etc — know exactly what’s going on. Those who are upstairs — the effortlessly wealthy, endlessly exercised and cosmetologized — float past in perfect non-awareness of social dynamics. But those who are downstairs get by through a willed blindness, and perfect discretion, towards the inequality saturating their existence. Alex, however, out of necessity, finds herself needing to break through the class demarcations. She opens the novel having made one effortless leap — making herself the live-in girlfriend to wealthy Simon, who seems not to have picked up on quite how mercantile their arrangement really is. But once she dents Simon’s car and he sends her back to the city, she needs to carry out a more acrobatic series of class maneuvers. She has to pretend to the housekeepers and house managers, who are very difficult to fool, that she is some stray member of the family. She sort of remembers that she is, after all, 22 and can maybe blend in with the rich kids spending the weekend in the Hamptons. And then, from there, it’s possible to blend in with the high schoolers and their absentee fathers, who are course less attentive than the housekeepers.

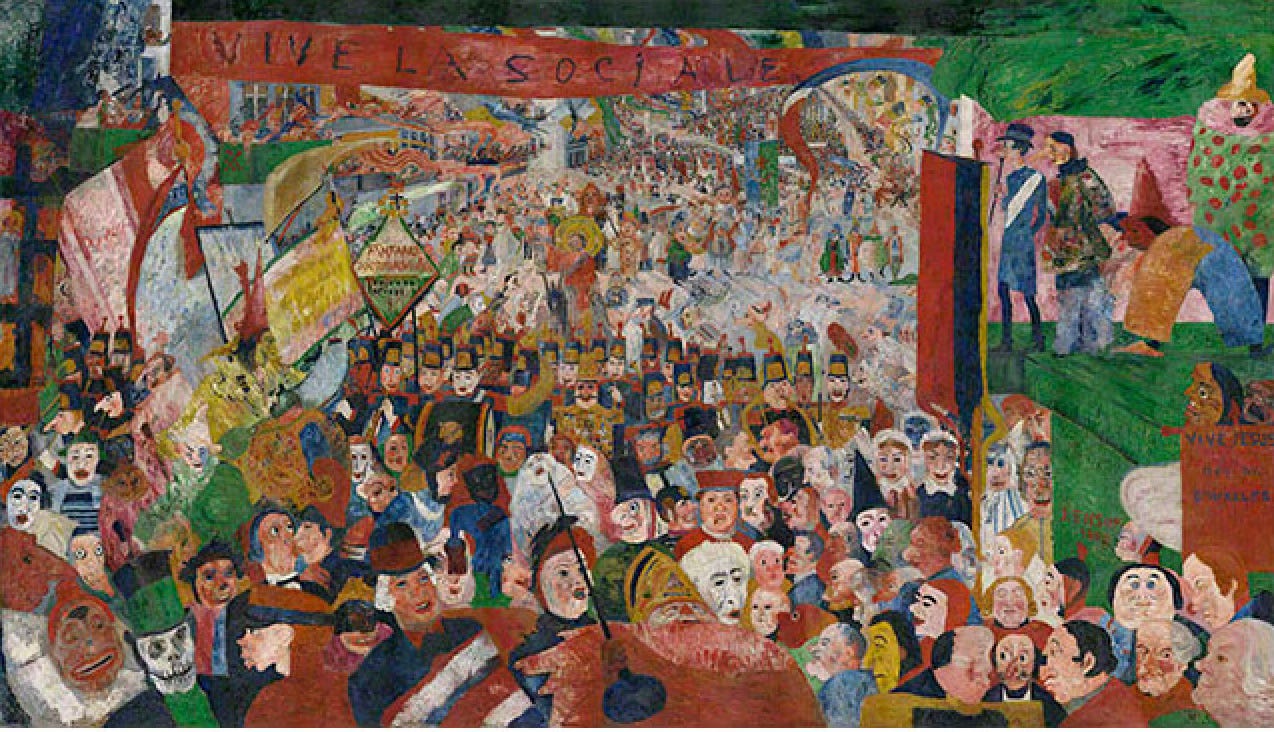

Everything about this is brilliant — like Catcher in the Rye if Holden were a hooker on painkillers — and it seems to point towards an underutilized genre in American fiction: towards the sort of expressionism that shows up in Nathanael West or James Ensor. No redemptive or upwardly mobile narratives are possible. The society is in a state of terminal decadence and the job of the novelist is to offer up a parade of the legions of all the damned.

That being said, though, The Guest is somehow far less than the sum of its parts. The ending doesn’t come together — it starts being apparent that it’s not going to work from about ten pages out — and that, actually, undermines much of the rest of the book. In retrospect, it turns out that none of the macro-plotlines hold together. I don’t know if I really believe that any of this is happening. That Alex is keeping her old number if she is so terrified of drug dealer Dom. That Alex has truly burnt through every one of her options and can’t return to New York City. That Alex is as composed and precise when she needs to be and then abruptly combusts whenever it seems time for the plot to move forward. And, as a character, Alex seems more the product of careful research than lived-in experience or imagination. She is rendered as a few checked boxes — small town, hinted-at trauma, no education, a drug problem — but just enough so as to drop her into a socioeconomic notch where she is pretty enough to pass as a rich man’s girlfriend but will never entirely belong.

It’s really a disappointment when the ending doesn’t cohere and much of what seems to be a careful novelistic architecture crumbles away. What’s left, then, is Cline as stylist and Cline hinting at an interesting direction for writing about the decadence of our era, but the novel is almost so much more than that.

NELLIE BOWLES’ Morning After The Revolution: Dispatches From The Wrong Side of History (2024)

A valuable, surprisingly emotional book.

By now, we’ve gotten used to the woke/anti-woke polemic, and it sort of seems like an unsettled, unfortunate bit of cultural history. The institutions are finding their sea legs again. The pandemic and the social upheaval of 2020 can, with broader perspective, be largely attributed to Trump’s hollowing out of some core integrity at the center of the society. As Bowles writes in her conclusion:

The years I spent reporting this book—the early 2020s—happened to be the start of the revolution. The first phase was ending as I wrapped this. The movement leaders were sneaking off with funds gathered in the height of rage, settling into pretty canyons. The rallying cries were being deleted from websites and memories. (No one ever said abolish the police, I’ve been told recently.) The word woke had gotten exhausting. It sounded dated.

But, as Bowles knows and reminds us, this wasn’t just Twitter fun-and-games. This really was a social revolution, bathed in good intentions but ultimately devouring itself. And it had far-reaching real-world consequences.

Bowles is best known as the sort of amiable sidekick to Bari Weiss. They left The New York Times and founded The Free Press together. Weiss was always the belligerent, public-facing side of the partnership. Bowles was far less provocative but clearly shared Weiss’ mission and she posted a very funny weekly round-up (and send-up) of the news.

The Morning After the Revolution (the title is a pun by the way) shows Bowles’ reportorial chops. The majority of the book is an incredulous, John McPhee-esque tour of the woke cultural landscape with Bowles trying to keep a straight face through all of it. She enrolls in a white fragility seminar. She visits autonomous zones and safe-injection spaces in Seattle and San Francisco. She chronicles San Francisco’s descent into what she calls “progressive-libertarian nihilism.” She charts out the self-eating cancellation chains.

Having lived through this, I thought I knew the most extreme excesses of wokeism. But no. And there is something really stunning in seeing it all laid out:

The facilitator at the white fragility seminar saying, “Whiteness is like an octopus. It has its tentacles in everything.”

The protestors/looters in Portland — completely unchecked by law enforcement — chanting “You’ll never sleep tight / We do this every night.”

The medical journal The Lancet in their effort to avoid transphobic language referring to women as “bodies with a vagina.”

The homeless activist in Los Angeles showing up to rallies in his BMW X5 (and then encouraging the homeless not to give in to the city’s offer of housing).

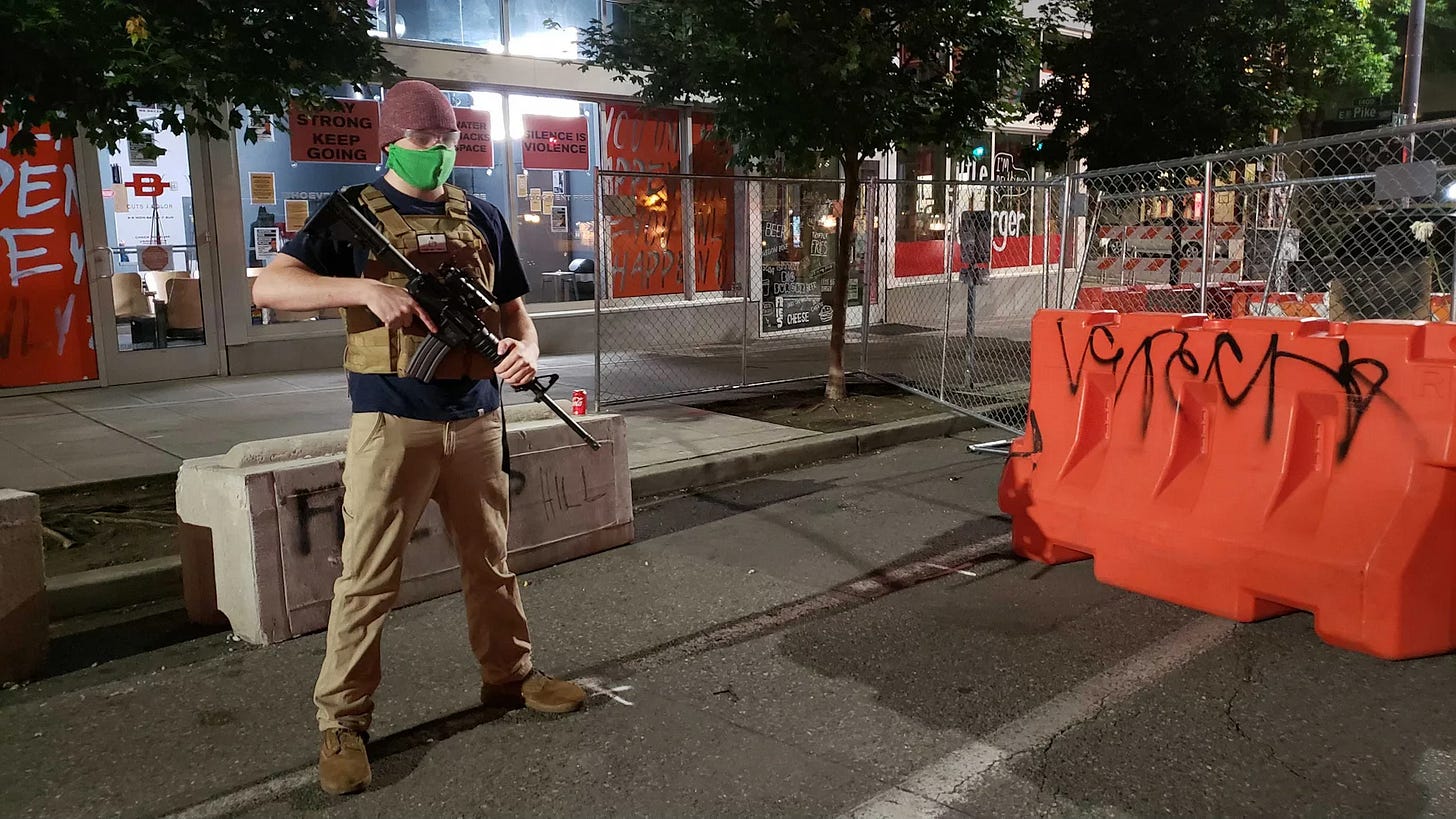

Amazingly enough, I had missed the story of CHAZ — the collective that carved out an autonomous zone in Seattle in 2020, that organized its own security and from which city police as well as emergency services (fire trucks and ambulances) were excluded — and which was the scene of steadily-escalating looting and several shootings until the city finally stepped in. Although maybe it’s not so surprising. Having ceded the underlying prerogatives of any government — the monopolization of violence and the right to maintain order — Seattle’s mayor simply refused to see any problem even as the evidence of looting and property destruction accumulated. “It has a block-party atmosphere,” she said. And, with a really startling abrogation of responsibility, the mainstream media declined to cover the story at all. This was the start of Bowles’ shift out of the orthodoxy (and, ultimately, The Times). An editor pulled her aside when she wanted to report on CHAZ and told her that she was ruining her career by writing on it.

I thought I knew, also, the most egregious instance of institutional Pilatism — “mostly peaceful protests,” that kind of thing — but seeing them all laid out is, once again, startling:

David Remnick concluding his New Yorker piece on the 2020 protests by calling looting “catharsis.”

A New York Post éxposé on the $1.4 million home purchase by a Black Lives Matter leader getting blocked on Facebook for “violating community standards.”

San Francisco’s city government refusing to allow reporters to view safe injection sites. As Bowles witheringly writes, “It’s an intimate private moment — on public ground — between the city and the addict….The city government said it was trying to help. But from the outside, what it looked like was young people being eased to death on the sidewalk, surrounded by half-eaten boxed lunches.”

The basic story, as I understand it, is that wokeism originated above all in universities and small private colleges. It found its cause célèbre in 2014 with the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson — and Black Lives Matter’s protest of police brutality. By the late 2010s, it had ossified into a progressive orthodoxy that subsumed liberal-minded late millennials and Gen Z. The liberal institutions — the major media outlets, schools, and local governments — didn’t quite know what to make of wokeism but assumed that it represented progress, and figured that at the worst it was a harmless display of youthful enthusiasm. The idea that woke initiatives were interesting or cute — whether the autonomous zones in West Coast cities, ‘abolish the police,’ white fragility workshops, trans-affirming language, etc — is the guiding thread in the institutions’ response. And then only belatedly did the institutions notice the moral traps they had built for themselves — with dissent, asking the wrong questions or pursuing the wrong stories, grounds for professional cancellation.

What most enabled the woke madness was the persistent belief that none of it was very serious — so much of it seemed to be happening on social media; or in colleges; or already-progressive enclaves in major cities. And it really did take a long time to pick up on the damage done to civic life by out-of-control protests or to the society-as-a-whole by the ever-present possibility of cancellation. And Bowles suffers a bit from the same problem — as a naturally funny person, she seems to keep having to remind herself that the whole thing is not a joke. Of a word-salad delivered by a law professor trying to explain police abolition, she writes, “Akbar launches into a sort of spoken-word academic poetry about what abolition means.” Of a scion of the Kennedy and Cuomo clans holding a press conference to announce that she was queer, by which she actually meant ‘demisexual,’ Bowles writes, “Michaela threw a coming out party to tell the world that she only wanted to date people she liked.” Of her experience on the giving end of a cancellation, she writes, “To do a cancellation is a very warm, social thing. It has the energy of a potluck.”

But what ultimately sets Morning After The Revolution apart is Bowles’ warm heart and empathy. She really was a believer in the progressive orthodoxies. It was the community she was in and the air she breathed. She knows (in a way that most of the conservative polemicists do not) that the woke warriors tend to be coming from a good place — “Even as I reported on the issues, I was constantly struck by the movement’s beauty,” she writes. “They see real problems, real pain. So many of the solutions should work. If only people behaved.” She writes with genuine sorrow about having dedicated so much of her youth to the progressive moment — and describes leaving it as an excruciating sort of growing up. “I think about the parts I loved at the start of the fragile, hopeful movement that really did bring new ideas into the world. Ideas around fairness, around language, around our bodies,” she writes. “I don’t think I’ll be around a group so optimistic again in my life.”

As Bowles fully notes, the woke progressives were right on a great many points. Systemic racism is real and is deeper and more unconscious than liberals had a tendency to admit. Marginalized communities were so often overlooked and brushed aside — and progressives worked assiduously to try to hear from people outside the cultural mainstream. Bowles, in her white fragility workshop, sheds very genuine tears when a facilitator says, “These black bodies were not immigrants, they were enslaved.” She is there to witness a member of a homeless camp saying, “They call us Invisible People, like we don’t exist. But if something happened, if they needed help, we’d be the first ones to help them because we’re representing God.”

But revolutions, social ones included, have their own destructive logic, and the woke revolution succumbed to those bitter paradoxes more quickly and disastrously than most. The cancellations became circular, the demands more unhinged, the corruption of progressive leaders more visible, the damage done by the movement more difficult to laugh off or excuse.

The tide definitely turned. The institutions, to some extent, developed a new backbone. New expressive outlets emerged — Substack most prominently — that were beyond the ambit of cancellations. The cycle of cancellations and ritual apologies seemed to taper off. Weiss and Bowles themselves were able to ride off into the sunset and start their own very successful publication.

But, as Bowles notes, it’s not quite as simple as the tide turning or the fever breaking, the world getting back to normal. It was a highly-successful, deep-seated cultural revolution. Bowles writes:

Did the quieter streets mean it was done? Hardly. The ideas became the operating principle of big business, the tech company handbook, the head of HR, the statement you have to write to get a job in a university. The movement fell apart because of how fully it succeeded. It didn’t need to announce itself so loudly anymore. We didn’t need to notice it anymore.

We will be living with the consequences of it for a long time to come.

Agree with your thoughts on The Guest, the ending did not cohere and ruined what was otherwise an excellent novel

I love that I can instantly find something to read in your New(ish) Books tab -- and that you also help steer me clear of many titles that I might unknowingly subject myself to.

For instance, I love that we agree about Ocean Vuong. And I appreciate how you give Cline even-handed treatment here, honestly noting what works for you, but not overpraising the book, either. I wish I could find more honest reviews like this, since pretty much every book has blurbs overselling it as a work of genius. But I'm certainly glad that I have yours as a staple.

Bowles looks like a must-read. Very much appreciate your attempt to resolve the woke/anti-woke binary here. I hope that your past tense "was" for this cultural revolution is right, and that it is firmly in our rear view, even if we are still climbing out of the wreckage.