Dear Friends,

I’m sharing a review/discussion on a pair of recent non-fiction books.

Best,

Sam

ALEXANDER WARD’s The Internationalists (2024)

A dutiful, serviceable account of Biden’s international team during the first, chaotic year of the administration.

I’ve been wanting to read something like this. My sense is that, because the Biden presidency isn’t a particularly charismatic administration, it’s destined to be largely forgotten — like Rutherford B. Hayes or something — which is too bad since the administration was dealing with very high-stakes, consequential decisions, and (to my mind anyway) has on the international front done very well.

Ward is a veteran Politico writer. He gets good access to the foreign policy team but nothing special — we really end up with very little image in our minds of Jake Sullivan, Anthony Blinken, Lloyd Austin, etc. We don’t get the expressions on their faces at pivotal moments. We don’t learn anything about their personal lives. I’ve been getting increasingly fascinated with Jake Sullivan. But less so after this. Sullivan just comes across as a figure of the Washington Blob — a bit grey, a bit colorless, carrying out a technocratic function. Of his chairmanship of NSC meetings, Ward writes, “He rarely if ever let his true feelings be known.”

Although I guess that is sort of what I find interesting about Sullivan and the Biden administration. The idea that, from the perspective of the United States and US interests, there usually is a right decision — and governance is largely about winnowing down options, looking at the hand one is dealt and then choosing the optimal solution. That it’s meant to be a bit colorless.

I’ve had the sense that, on the foreign policy front, the Biden team really has been an remarkably effective steward of American interests. They were able to thread the needle on Ukraine, keeping Ukraine alive, avoiding a direct confrontation with Russia, and regaining much of the US’ moral stature. They recognized the need for a pivot away from unfettered globalization and back towards a consolidation of defense and industrial capacities. They supported Israel when Israel needed it — and then started to push when Israel overstepped in Gaza. And even the Afghanistan withdrawal may, ultimately, have been the right decision and carried out at the right time — early in the administration when there was time to recover from it.

But that sense of the high-optimizing, smooth-flowing foreign policy team only comes in later in the story. For most of 2021, it’s a mess, and as sympathetic as Ward is to Sullivan and co, it’s clear that the administration gets very much overtaken by events.

Ward’s narrative is that Biden came into power aiming for a “foreign policy for the middle class” — that utterly nebulous idea that Sullivan, and NatSec Action, concocted in the political wilderness — and for a general retrenchment and heightened modesty, but that the events of 2021-2022 compelled the Biden Administration to be more internationalist than they ever intended. “Bidenism in action” is described as the US being “more humble about what it could achieve.” That meant the withdrawal from Afghanistan, and ending of the Forever Wars, which Biden hoped would be his primary legacy — a decision that threaded back to Biden’s position during the Obama administration when he had been the leading advocate for withdrawal and felt that Obama had been boxed in by the military. “Biden would not make the same mistake. He would not back down, because he had been right before,” Ward writes. In one of the very few stirring moments in The Internationalists, he tells a skeptical Mike Milley that the withdrawal really will happen — and it becomes abundantly clear that Biden views it above all in moral terms. “The easier call is just to punt. I didn’t become president to do the easy thing,” he said.

And that sense of withdrawal and modesty extended to China, where the incoming administration “found merit” in Trump’s policies and continued the premise of on-shoring industrial and defensive capacity; and to Russia where, initially, the Biden Administration was conciliatory to Putin, even to the point of “mistreating” and betraying Ukraine with a series of diplomatic snubs and then by giving the go-ahead to Nord Stream 2.

But there was, as one official told Ward, “an arrogance in the humility” of the Biden people. They were so determined to wind down Afghanistan, and to do it on something like a predetermined schedule, that they were slow to react to events on the ground: they didn’t expect the Afghan army to melt away at the rate it did, they had a tendency to disregard military advice, and their decisions, as one advocate working closely with the administration at the time observed, were “scattershot.”

The disaster of the Afghanistan withdrawal (it probably always was going to be a disaster no matter when it happened, but there was no question that the administration botched its execution) was an existential crisis for the White House. In one of the very few revealingly human moments in The Internationalists, a friend of Sullivan’s says, “That wasn’t the Jake we knew — he was rocked.” And Sullivan — the master debater, the consummate technocrat, always smooth, always confident — seemed for the first time in his life to really be overmatched.

The question that’s been in the back of my mind for the last couple of years is whether the Afghanistan withdrawal really was the trigger for the Ukraine invasion — and that’s dealt with surprisingly directly in The Internationalists. Ward writes:

A key theme arose as US and European officials spoke to each other [in late 2021]. Putin was planning to invade not only because he hated Ukraine’s existence but also because he sensed Western weakness. Putin, the ultimate geopolitical shark, sensed blood in the water.

If that’s the case — and it seems like it was — it’s a serious indictment of Biden administration policy in 2021. Biden tried to do the “hard thing,” but — as Obama had sensed in the 2010s — that was a geopolitical miscue, and would result in aggressive action by the US’ superpower adversaries. The greater consensus that comes through The Internationalists’, though, is that Putin really was “unhinged” and operating from an irrational place. That was Sullivan’s strong belief, and Ward reports on a series of calls between Biden and Putin, in which Putin was entirely focused on historical wrongs and, in Biden’s view, not making sense.

The inside baseball here (which I had somewhat missed) is that Putin did offer a way out in demanding a Western commitment that Ukraine, together with Georgia, would not be admitted to NATO. This made German Chancellor Olaf Scholz buckle — telling reporters that it wasn’t worth risking World War III for the sake of NATO’s “Open Door” admissions policy. But, for the US team, that was never really an option — the Open Door policy was at the heart of NATO and couldn’t be revoked at the barrel of a gun.

If 2021 had been a case of acute growing pains, 2022 really was masterful foreign policy. It was, as one official said, “the ultimate land of bad options” — how to protect a highly-vulnerable ally that wasn’t contained within NATO alliance guarantees — and the administration seemed to make one right move after another. Arms flowed to Ukraine but without crossing Russia’s red lines. The European coalition held together. The Ukrainian military turned out to be far more robust than anyone suspected. From here, Ward seems to have less hands-on reporting and to be drifting more into hagiography. But his basic premise is that it was as it seemed: Putin really had stepped out of the realm of the rational; the Sullivan-led national security team found its sea legs and proved itself an effective leader of a new, Ukraine-inclusive, shotgunned alliance.

For Ward, it was an adaptation to a shifted reality — Russia could no longer be counted upon to abide by the international order; and the United States had to hold the line against great-power aggression — but it was a deviation from what the Biden administration really hoped to achieve. That vision — which ran through Afghanistan, CHIPS, and was articulated publicly by Sullivan in his 2023 Brookings speech — was, as Ward puts it:

the need to return to fundamentals: a healthy middle class powered by a humming industrial base, a humility about what the US military alone can accomplish, a solid cadre of allies, attention to the most existential threats, and a refresh of the tenets that sustain American democracy.

In foreign policy terms, there’s more in there that’s aligned with the Trump administration than one might expect — a shared consensus about China; a focus on superpower competition as opposed to ever-more-entangled commitments around the world — but it’s also a walk back from the Bush and to, some extent, Obama years. The idea is that the US can only do so much. That the alliances are critical. And that United States foreign policy is only as good as the options placed in front of it.

JONATHAN HAIDT’s The Anxious Generation (2024)

One of these slightly finger-wagging books that’s clearly right about almost everything.

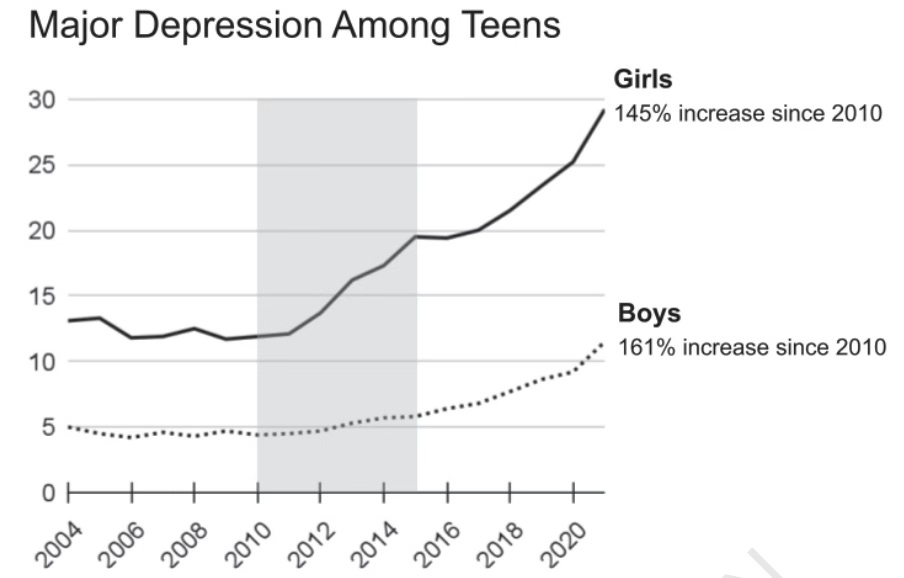

Haidt’s point is that the rise of cell phones, and social media, can’t really be understood as technological advance or normal generational permutation; it’s decimating to our basic psychological structure. And that becomes bracingly clear when you zoom in on the data and focus only on children who grew up saturated in digital media. Isolation, self-harm, anxiety, depression are all way up — and the data is very clear that those trends are experienced all over the western world and can only be attributed, really, to the smart phones.

But Haidt’s critique is somehow even deeper than that. It’s that the normal developmental process for human mammals has been stunted in unprecedented ways by two separate but converging trends — the rise in “safetyism,” starting around the 1980s, with the focus on removing all possible harms from childhood at the expense of independent play; and then the onslaught of the phones starting around 2010. The overall trend line is from a “play-based” to a “phone-based” childhood and the result is “the anxious generation,” a “rewiring” of the grounding of our experience from boredom to anxiety. Present-day western children are simply not maturing as they need to; they are not engaging in physical space around them, they are not socializing through face-to-face interactions, they are not taking risks and learning their limits; they are facing a flattening of experience as occurs in digital space; and they are receiving copious outputs that the physical world around them is full of harms and needs to be avoided.

As Haidt writes:

This is the world that Gen Z grew up in. It was a world in which adults, schools, and other institutions worked together to teach children that the world is dangerous and to prevent them from experiencing the risks, conflicts, and thrills that their experience-expectant brains needed to overcome anxiety and set their default mental state to discover mode.

I agree with everything Haidt says. It hits home and strikes deep. I did have this odd padded-walls sense about my own childhood. My parents were anxious to counteract that, to ensure that there was time outdoors, to avoid coddling. But it somehow was impossible. Even in New York City, things were somehow very safe — there was a surprising paucity of risk-taking, of formative experiences. And what was striking about it was that it wasn’t the fault of any one thing exactly. Haidt probably hits close to the mark when he says that there was “a breakdown in adult solidarity.” Adults felt — whether because of moral panics or the atomized structures of modern life — that they couldn’t trust one another to keep an eye on free-roaming kids. Childhood became the responsibility of nuclear families and with parents socially incentivized to take ever-greater, more active roles in their kids’ upbringings. This came at the expense of socialization with other kids, at the expense of the vital interplay of boredom-and-creativity, at the expense of normal processes of growth and initiation into a wider community. Childhood became a cocooned, cordoned-off zone that fringe adults and older kids were not permitted to intervene in.

Then the smart phones came in and produced the worst of all worlds. They made a mockery of the principles of safetyism — the adults were still actively reducing harms in physical space but their kids were finding all sorts of non-age appropriate experiences on the internet. Haidt cites a bracing essay by Isabel Hogben, who describes her attentive, helicopterish mom busying herself with giving her daughter “nine differently colored fruits and vegetables on the daily,” while Isabel, at 10 years old, was meanwhile discovering hardcore porn in the next room. And then the phobias about the physical world were still there but exacerbated by the addiction to screens — it became the path of least resistance for parents to just let their kids be on devices all day, while the kids became less and less engaged with the actual physical world, until the kids developed anxiety and depression at which point the parents responded with an extra dose of coddling.

So: agreed on all of it. But, as often with this type of work, the solution falls short of the problem. Haidt’s idea is to dramatically restrict access to phones in childhood —no smart phones before 14; no social media before 16; no phones in schools — and for communities to link together to enforce these standards. It sounds nice. It brings up all kinds of pleasant cultural memories — Charlie Brown and his gang roaming around the suburbs, if not Tom Sawyer and Aunt Polly’s fence. But I just don’t think it’s going to happen.

Haidt claims that he’s gotten tired of transportation metaphors — ‘the ship has sailed,’ ‘the train has left the station.’ He proposes a new one: bringing the plane back to the gate when a safety issue is detected. But, as I think Haidt suspects, the problem is deeper than that. His claim is that the smart phones have been around for only a decade or so, that there’s still time to undo the Great Rewiring. But the Great Rewiring is not occurring only in childhood. It’s what adults are doing and it’s reshaped the entire economy. This may be for better or for worse — it’s probably for worse, but that’s not really the point. It’s just the world that everybody is inhabiting. It doesn’t matter how many wilderness camps kids are sent to, how much unsupervised outdoor playtime they have — they won’t end up like Charlie Brown palling around the suburbs with his friends or Tom Sawyer machinating around Aunt Polly’s fence. Aunt Polly now is sitting in her living room on her phone. And the kids who have the feeling that they’re missing out if they’re not on their phone all the time are right — they are missing out. They are going to have to inhabit a digital world that’s unfamiliar to all of us and for which our guidance is of only limited utility. They sense that their education requires taking in that space — mimicking what people older than them are doing on that space; and then, as they get older, outcompeting the adults on that space. Even more than play or physical risk-taking, that’s the deeper meaning of childhood — the looking-up-to and then gradual supplanting-of the adult world — and, for present-day kids, that can only be in the digital realm.

The diagnoses are all accurate, but there is no cure. Technology has brought us to a dystopia, which is unnatural, inorganic, developmentally-stunting, et al. But there is nothing we can do except to navigate it.

The term platform is key in understanding how social media is a theatrical experience. We lose sight of its structure when we discuss it as mere literary discourse. As in conventional theatre social media has its hierarchy of Svengali style producers, talented teams of technicians designing the stage sets, a large cast of paid actors and a paying audience. The notable difference is in how the audience pays twice. The first time knowingly in signing up and the second time unknowingly as their personal life experiences are algorithmically harvested.

Social media is a new form of very profitable voyeurism. It functions through multi layered and often invisible abuses of power. At the moment it’s producers are being back footed by the increasing numbers of individuals suffering often fatally from the fall out of their violations of privacy and person. But as with all abusers they victim blame - only a few ‘vulnerable’ types who would be damaged anyway and/or it is all down to bad parenting etc…- whilst they loudly continue to control their victims narratives.

Eventually, however sophisticated the initial grooming processes, all sentient beings reject bullying and abuse through various forms of disobedience. There was an interesting related article on The Pragmatic Optimist: We Scroll More than We Post - The Great Media Reset by Uttam Dey and Amrita Roy. It outlines the increasing rejection of engagement with social

media by younger generations. Quoting Wired magazine’s Cory Doctorow’s term ‘enshittification’ as a description of the ongoing diminishing of user’s experiences and subsequent lowering of profits for platforms as they lose their abused audience.

I dig the conclusion because you’re right, lamenting the current state of technological affairs does nothing to change it. As with any potential toxic behavior, the best way to combat it is to lead by example. Making clear, conscious choices to actively limit smart phone use remains the best way to stay human in my experience.