Dear Friends,

I’m sharing ‘New(ish) Books’ of the week. These are more in-depth discussions of books than reviews. I usually pair fiction with non-fiction, but this time, for some reason, it’s two non-fiction books that both deal, in bracing ways, with the realities of power.

Best,

Sam

MICHELA WRONG’s Do Not Disturb: The Story of a Political Murder and an African Regime Gone Bad (2021)

A brave and impressive book.

I really know nothing about Rwanda — or know the broad outline that everybody knows: the plane; the genocide; the West’s failure to intervene; the rebel army eventually putting a stop to it; the transformation of Rwanda into something like a model African state.

Wrong offers a counter-narrative on this, assailing every single point of the accepted history. As she wryly notes, her counter-narrative “has not made [her] popular in Kigali.”

I have nowhere near enough knowledge to try to assess her claims, so I’ll just deal with them on flimsy terms: summarizing what she says, dealing with her narrative as if it were a movie treatment or a study in power.

As a movie — and it was playing this way often in my head I was reading Do Not Disturb — it is, as Wrong writes, “the story of a small, tight-knit of Rwandan elites” and how their friendships and rivalries play out over several decades.

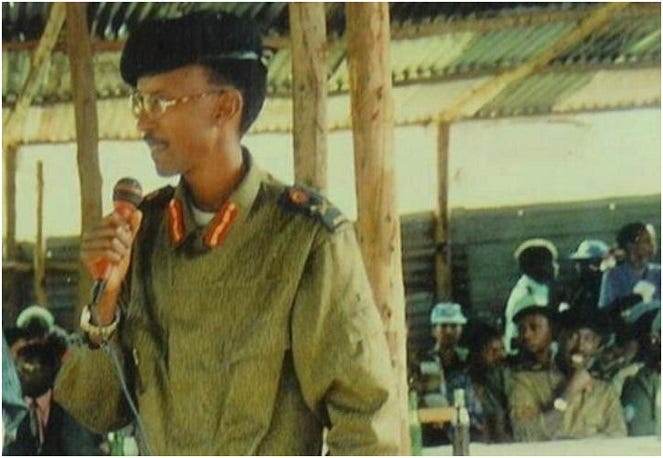

The opening is in 1959: the exile of Tutsis from post-colonial Rwanda, their settlement in Uganda, their humiliations, their dreams for a return. The really critical scenes are in the Bush War of the 1980s, the Rwandan exiles fighting with Yoweri Museveni’s National Resistance Army in Uganda. The Rwandans, although they have no clear stake in the fight, are ferocious, even reckless soldiers. The two main characters are Fred Rwigyema and Paul Kagame, and they are a study in contrast. Rwigyema is the perfect guerrilla leader — dazzlingly handsome, charismatic, compassionate, both a daredevil fighter and a skilled builder-of-diplomatic-bridges. And then there is Kagame, in charge of intelligence, always suspicious, unpopular, “always tamping down some inexplicable inner fury,” with a predisposition for asserting discipline, “a tremulous shadow hovering around [Rwigyema’s] alpha male figure,” Wrong writes.

In the Bush War, their group — the RPF (Rwandan Patriotic Front) — develops its characteristic qualities: cohesiveness, discretion, a reputation for discipline. They also develop a distinctive method for disposing of unwanteds — of locals they meet along the way that they fear will give away troop movements; of volunteers who have second thoughts about the cause. This is ‘kafuni’ — a method of digging a ditch and carrying out a quiet execution with a short-handled hoe to the back of the head. “Say you were going on a patrol at night. You come across a villager who is very humble, a simple person, friendly, drunk, willing to please. You pass him back down the line. And that happens once, twice, three times. You keep passing these people back down the line. Later, when you return to the unit, all those people are gone,” recalls a member of the RPF from around this time.

The Bush War ends with Museveni’s victory, with Rwigyema as a major general in the Ugandan army and as a sort of adopted son of Museveni, and then, with Museveni on a trip to New York, the RPF suddenly peels away from the Ugandan armed forces and invade Rwanda. This is one of many split-screen moments, in which history can be interpreted in different directions, but in this case Wrong agrees on the generally-accepted version: that Museveni did not know what the RPF was planning, that the RPF represented an idealistic rebellion of exiles rather than a coordinated Ugandan invasion.

But, on the second day of the war, tragedy strikes — this being another one of these split-screen moments. Rwigyema is killed, and nobody has ever quite figured out what happened. The RPF story is that, as was habit, he wandered to the front line and was killed by the Rwandan army. The Ugandan version is that he was embroiled in a dispute over strategy with two lieutenants and one pulled out a gun and shot him. The loss of Fred reverberates through the movement. “It was only Rwigyema who mattered,” Museveni would say. And, years later, with the RPF marching triumphantly through Kigali, fighters would admit to hoping against hope that Fred would somehow emerge at the head of the parade.

But, instead, Kagame — on training at Ft Leavenworth at the time of the invasion — returns to Rwanda and takes command of the RPF. “He was unpopular with the officers, his leadership was questioned from the get-go,” says one of Wrong’s sources, but he was the only member of the leadership circle who was acceptable to all sides, and above all to the Ugandans.

By 1994, which is — as Wrong writes — when “history starts” for most people who know nothing about Rwanda, the RPF is making steady progress through the north of the country. The fear, broadcast on Hutu radio networks, is that — as a Hutu nun put it to Wrong and journalists at the time — that “the RPF had dug big cement vats where they were going to throw all of us.” The plane of President Habayrimana is shot down and that’s the trigger for the genocide, with Hutus hacking down Tutsis across the country.

Wrong passes over that familiar story fairly quickly. What she is interested in is the counter-narrative. “Reporters would later recall, with retrospective unease, how eerily quiet the first areas captured by the RPF had always seemed,” she writes, and “The French always believed in a ‘double genocide’ theory.” In other words, she is saying, the practice of kafuni continued on a massive scale in areas under RPF control. She tells the story of a group of humanitarian workers coming across 150 bodies, shot up and laid out in an area that had long been vacated by government and Hutu forces. She describes a practice of summoning locals for a peace-and-reconciliation-meeting, and, once the group is gathered, massacring everyone on the spot. And, she comes up with a counter-narrative for what happened to the president’s plane. Patrick Karegeya, long-time external chief under Kagame and the principal hero of Wrong’s book, fled Rwanda in 2007 and told the British High Commission in Uganda, “I was part of the team that brought down the plane.” Karegeya’s contention was logical enough. The plane was brought down with a Soviet-made missile — the RPF, through Uganda, were the only ones who would have had the connections to Soviet-made weapons at that time. The RPF had the motive — they were at war with Habyarimana and “craved a definitive, knock-out blow.” As for the now-generally-accepted version that the plane was brought down by Hutu extremists, Karegeya, Wrong writes, “marveled that anyone had been credulous enough to fall for it.” And, as for the plane instigating the genocide, “Kagame didn’t know that would happen, but it didn’t matter, he didn’t gave a damn,” Karegeya said.

Wrong’s thesis creates a very different understanding of 1994 — it shifts the emphasis away from the genocidal Hutus and the innocent Tutsis. Instead, there’s a fog of war scenario in which both sides are responsible for atrocities, with the Hutus’ crimes more visible to the outside world.

Assuming that Wrong is basically correct, it’s very hard to know what to do with that knowledge. The standard liberal view would be that it creates a false sense of both sides-ism and undercuts the horrors of the genocide. Wrong’s view (which is heavily indebted to Karegeya’s) is that the perfidy of Kagame, both the habit of kafuni and the assassinations of rivals carried out after he was in power, delegitimizes his regime. For me, thinking about this completely from the outside, it serves as a searing lesson in the realities of power. Some sort of representative democracy seems not to have been an option in Rwanda’s case. Habyarimana was, as Wrong writes, “a military man through and through.” Kagame was at the head of a rebel army — and limited by being less than charismatic, by having shaky control over his own ranks. As Wrong writes, the RPF never really transitioned to civilian government; they kept everything, their military discipline and vigilance, intact from the bush. And Kagame was an enthusiastic practitioner of what one of Wrong’s sources calls the ‘Beria method of rule’ — the idea being that it was amateurish statecraft to target only one’s enemies; that the real statesman targeted their friends as well. As another source says to Wrong, “Paul Kagame is the most ruthless politician in Africa,” but it becomes somewhat difficult to argue, from the assembled facts of Wrong’s narrative, that some other method of rule is readily at hand. A fellow journalist says to Wrong, “Remember the bodies in the street, don’t you think things turned out rather well, everything considered?” and this brings her up short. It seems very clear that Kagame quietly carried out a large number of massacres and assassinations over his nearly thirty years of rule, that underneath the facade of modern Rwanda — always touted as ‘the poster child of Africa’ — was a “form of internal terrorism,” but there is a competing view out there that those methods were worth it as the price to pay for security.

In the movie version of Wrong’s story, the pairing of Kagame and Rwigyema is replaced, after Fred’s death, with the pairing of Kagame and Karegeya. Karegeya is a principal source for Wrong’s material. The counter-claim from Kigali is that Wrong and Karegeya were allegedly having an affair and the book serves as his posthumous hatchet job against Kagame. Without giving any credence to that rumor, the passages on Karegeya do come across as written by someone with a deep affection for him. He is described as being so funny, so charming, so incorruptible — such a vivid contrast to Kagame. It becomes necessary to stop oneself at different points while reading Do Not Disturb to remember that Karegeya was Kagame’s external intelligence chief, that he was complicit in many of the same operations as Kagame — was, by his own account, part of “the team that brought down the plane”; that he ran the ‘Congo Desk’ and was part of the wholesale plundering of the Congo in the late 1990s; that he (again by his own account) was responsible for the assassination of Laurent Kabila, the Rwandan-installed president of the Congo. As one of Wrong’s interviewees said, “Karegeya was very friendly, very open, very charming, and underneath, a killer, of course.”

Wrong is largely encountering Karegeya after he and Kagame had already had a falling out, when he had fled to South Africa and was organizing a resistance movement to Kagame. A disproportionate amount of her narrative is about this period, about the various ineffectual attempts by Kagame to assassinate Karegeya and the other opposition figures in exile — before finally succeeding with a hit on Karegeya in 2013. That’s a bracing story, a murder mystery in which the culprit is obvious, but a relatively minor crime compared with all the others that Wrong lays at Kagame’s feet.

Wrong’s hope, clearly, is to carry on Karegeya’s truth-telling, to unravel some of the mythologies around the genocide and which have contributed to the sanctification of Kagame and the RPF, to push towards a more equitable ethnic power-sharing arrangement in Rwanda. I have no idea what becomes of that project. What’s revealed, for me, in Do Not Disturb is an understanding of violence and power without the democratic, liberal emollients. Nation-building is a bit of a farce in a region where the powerful forces seem always to be coming from the outside — the powers-that-be in Uganda coming from Tanzania, those in Rwanda coming from Uganda, those in the Democratic Republic of the Congo from Rwanda. “The revolutionary leaders of the Great Lakes resembled a set of wooden Russian dolls,” Wrong writes. Coalition-building and democratic politics are hard to sustain given the seething ethnic undercurrents and given that “progressive dictatorship” appears to be a more practical and efficient type of regime. “A vibrant civil society no longer seemed a priority,” Wrong writes of the recent history of the Great Lakes Region — and with the Chinese model serving ever more as inspiration to rulers. Narratives of rebuilding from the genocide are to be understood in a political context — as pleas for more aid and for strengthening the power of the Tutsi elites. “There’s ‘Never Again’ and then there’s ‘Where were you?’ It’s really a very cynical ploy,” says a RPF dissident. And then there’s the way in which power is understood to be an extension of the personality of the leader. “The ultimate control freak, the class geek has created a state in his own image: introverted, suspicious, unaccountable, and a prey to sudden violence,” Wrong writes of Kagame. But it’s not completely clear that a state run by Fred Rwigyema or Patrick Karegeya would be all that much better — it would just be a reflection of their personalities. Read Do Not Disturb and many of the comfortable narratives about how power is supposed to work fall away. In Wrong’s account, power is the monopolization of violence — that and nothing else.

GREG BERMAN and AUBREY FOX’s Gradual: The Case for Incremental Change in a Radical Age (2023)

“Incrementalism is profoundly unsexy at the moment,” write Greg Berman and Aubrey Fox — and this is a profoundly unsexy book. An argument for thinking small, measuring expectations, moving slow. I found myself annoyed by it — much of Gradual deeply conflicts with my own worldview — and also far more engaged than I expected to be.

Gradual is like a hymn to bureaucrats, a full-throated rumble from the Deep State. The claim is that the majority of political rhetoric is basically posturing — much of it idealistic and well-intentioned but, in practice, achieving very little and often generating unforeseen consequences. And the actual work is done by unsung mid-level bureaucrats, who accept all the many things that they cannot change but work gradually and incrementally at effective reform.

The perspective is straightforward enough. “Our default setting should admit the obvious: our problems are big and our brains are small,” write Berman and Fox. “If there is one idea that serves as the intellectual foundation for incrementalism, it’s that human beings, who always face severe cognitive, conceptual, and political constraints, cannot operate according to a comprehensive ideal.” And in a world of unfathomable complexity — of constant friction between those in power, of the inevitable running-aground of all idealistic schemes — incrementalism remains the sole means of keeping things moving while generating meaningful reform. “Incrementalism is the lubricant that oils the machinery of American government, allowing the entire Rube Goldberg contraption to keep lurching forward, however fitfully,” write Berman and Fox. “Almost all of the actors within the system are incrementalists in practice, even if they are reluctant to articulate incrementalism as an overarching political philosophy.”

I guess I don’t disagree with any of that. I’m also suspicious of radical raptures; agree that ‘incrementalism’ is a decent way of describing how the real world works; appreciate Berman and Fox’s efforts to line themselves up with a ‘Burkean philosophy’ that’s not just stick-in-the-mud conservatism. And accept that, even if much of what Berman and Fox are saying is obvious, there is a need for it at the moment, when symbol seems ascendant over substance and political rhetoric insists always on ‘bold solutions,’ almost regardless of what those are.

But Berman and Fox often seems o be saying two different things at the same time. On the one hand, they are making the case that, contrary to everything anybody might reasonably assume, things are actually going fine. There is, quietly, a bipartisan consensus in Congress; and Congress is able, generally, to push through the kind of legislation that matters to people. And the ship of state keeps rolling forward — with many of the more substantive decisions already dealt with via precedent; and with most debate, for all its sound and fury, really just chipping away at the margins of already-established policy. On the other hand, though, Berman and Fox insist that they are really reformers — that “incrementalism is not a defense of the status quo and calls for ceaseless change.” Their point here is that meaningful reform can only come from those who are already in the corridors of power, who know what they’re doing, who respect the process and the delicate social ecosystem of the society.

On the second part I don’t disagree — that seems like a reasonable-enough handbook for reform. But, on the first part, it’s a little hard to see why Berman and Fox think things are going as well as they say they are. One of their hero budgeting specialists, Aaron Wildavsky — there are many such figures in Gradual — is quoted as saying, “The budget might be conceived of as an iceberg with by far the largest part below the surface, outside of the control of anyone.” In the view of Berman and Fox, that’s great — it means that fights are avoided and precedent respected; since we’ve been muddling through up to this point, goes the argument, no reason why yesterday’s successful muddle can’t remain as today’s policy. But it’s hard to exactly accept that. I mean, the national debt is skyrocketing and seems well past the point of being reined in. The budget is completely misallocated — with, famously, far too much going to defense. And, meanwhile, we’re the wealthiest country in the world and we have a crumbling infrastructure and lack basic services. So I’d have trouble seeing how gradualism, as described by Berman and Fox, is working. And, in these passages, what’s described really does sound like a recipe for following the status quo — exactly the sort of incrementalist mentality that made Hoover stick to reigning economic wisdom when the Depression hit; that kept the antebellum Congresses from dealing with slavery for decades.

The overall sense I get from Gradualism is that it turns bureaucracy into a sacred cow — makes people believe that the good civil servants are working zealously at all times; that if it seems like nothing at all is happening, that’s probably an optical illusion, that the wise system is moving in the right way for the right reasons. In Berman and Fox’s view of the world, even bureaucratic obfuscation — the holy writ whereby bureaucrats must leave the office at 5 sharp every day — is elevated into a noble calling. Gradual quotes Linda Rosenberg, in the context of the resistance to Trump, calling the heroic paper-pushers to arms: “In many ways, you are the last line of defense against illegal, unethical, or reckless actions. History has shown us that implementation of such policies depends on a compliant bureaucracy of obedient individuals who look the other way and do as they are told. Do what bureaucracy does well: slow-roll, obstruct, and constrain.” Follow the implications of what Berman and Fox are advocating for, and ‘incrementalism’ itself starts to seem like the goal — anything that the radical reformers do is, by its very nature, disruptive and not to be trusted, while anything done by the bureaucrats is ‘incremental’ and reliable (even if the bureaucrats are often, as in Rosenberg’s injunction, quietly setting policy themselves). To get history to match their vision, Berman and Fox have to do some sliding-around. Robert Moses and Lyndon Johnson, for instance, become utopian crusaders, pushing through unrealistic proposals, and are, in some cases, tackled back to reality in time by incrementalists — for instance, by Jane Jacobs, in the case of Moses. Meanwhile, successful reforms like social security tend to be made by people who get the value of incrementalism, like FDR, and understand the virtues of starting small and working through the system. But Moses and Johnson were hardly radical outsiders, and it’s a real stretch to try to spin Franklin Roosevelt as an incrementalist. All of them were powerful people who understood how to work the system’s levers, and part of their trick — particularly for a bureaucrat like Moses — was to make really radical, disruptive change appear as if it were incremental and all just part of the process. This is most vividly illustrated in Moses’ dictum that once you start digging into the ground, it’s very difficult to roll back construction. In other words, bureaucracy just tends to go along with whatever is already happening, and that may seem like ‘incrementalism,’ but, as often as not, what appears to be ‘reality’ is just a ploy by some master manipulator, and what’s needed to stop that is exactly the sort of individual courage that’s unaccounted for in Berman and Fox’s model.

But I am aware that the way I’m thinking about the world is completely different from how Berman and Fox do — and I’m not at all sure that my perspective is right. It’s almost like the division in physics where large objects in the universe are subject to relativity and small objects to quantum mechanism — that there is one set of laws for the individual and another for the collective. For the individual, what matters is intuition, courage, personal fulfillment. For the collective, Berman and Fox are arguing, what matters is consensus, mass employment, everything just moving forward, muddling along. Which is very close to the founding principle of the U.S. More and more I’m becoming aware of how much of the relative success of American democracy is the result of James Madison’s deeply unsexy vision — all about balance, all about having a large, factionalized nation in which the extremes would cancel each other out and a moderate ship of state would prevail. Berman and Fox discuss an episode I had been unaware of — in which Jefferson wrote to Madison advocating for a regular (every 20 years or so) revoting on the basic principles of the Constitution, which would have been a genuinely democratic proposal, and Madison responding that it was better to leave well enough alone. Which really is a telling fissure in political theory. Had Jefferson’s proposal been enacted, we might very well have cleared up the parts of the Constitution that the framers almost inarguably got wrong — the electoral college, the rules of the Senate, that ambiguous comma in the Second Amendment. But, on the other hand (and Berman and Fox take this outcome for granted), the republic might well have pulled apart at any one of these Constitutional re-votes. So what we’re dealing with in the U.S. — and what’s taken us this far — isn’t so much democracy as Madison’s incrementalist vision: extraordinarily limited popular control over government itself and government as a sort of self-perpetuating machine. As Berman and Fox keep having to say, there is nothing about gradualism that stirs the spirit, that would possibly be exciting to anyone — except that, as they quietly and compellingly argue, that’s what works and anything else tends to be fantasy.