BRANDON TAYLOR’s Filthy Animals (2021)

Thought-provoking. An interesting book.

Virtually every interaction in Filthy Animals has the same underlying tension. On the one hand, there’s an effort to see things from a perspective of a loose, easygoing society that’s invested in pushing its limits – discovering how to be in a thruple, how to be bi, how to joke about sensitive issues without offending – and then, on the other, there’s a perspective in which every one of these innocent, exploratory actions is inflected with trauma, and every intrusion into somebody else’s life, no matter the apparent motivation, is in fact a form of dominance and exploitation. This is sort of the big political question at the moment – is it possible to be innocent?; can an action be judged by itself or only in the widest possible historical context – and Taylor neatly straddles that fault-line, his characters arguing back and forth from its opposite sides.

I am not a dispassionate observer of this debate. I am in the camp of agency and innocence. I don’t find the sexual overture of Charles and Sophie – the central action of the novel – to be cruel or coercive, my reaction is that it can be taken at face-value, that Charles is a bit lost in his life but exploring, genuinely curious about Lionel, and has a style of flirtation and of sexual banter that always verges on rudeness, that always brushes against sensitivities – and, as it happens, Lionel is very attracted to exactly that side of Charles. But there is something greedy and entitled about Charles and Sophie. I understand that that would give Lionel pause and would make Taylor hover over them, constantly questioning their deeper motives.

The climax of the novel neatly encapsulates this ambivalence – Charles kissing the keloid scars where Lionel had slashed his wrists. “He kissed the heel of Lionel’s palm, and then moved down the tributaries of his veins, down the whole length of his arm,” Taylor writes. “Kissing him again and again until they were face to face. It was an ugly, cruel thing to do, Lionel thought. It was as mean a thing as he could have imagined.” That’s the verdict of Lionel – and of Taylor – but, somehow, I don’t think they actually mean it. It’s obvious that Charles is pushing things but isn’t cruel or malicious. And the premise that Lionel’s suicide attempt has turned him – at skin-level – into some kind of a horrific, frightening Other is completely negated by Charles’ very genuine affection, just as the premise that Charles has the upper hand in the relationship is canceled out once Charles admits that he is probably finished as a dancer and submits to his own moment of vulnerability, allowing Lionel to shave his head and burn his hair. “I think it’s possible for my life to be shitty and for your life to be shitty” is Lionel’s concluding thought of the novel – which, I think, catches him (and maybe even Taylor) by surprise. Suffering isn’t actually ranked and there isn’t some deep value or truth that accrues from proximity to pain – “there was nothing noble in suffering,” Taylor writes – and, in the buoyant, innocent mood of the novel’s ending, narratives of collective responsibility and accumulated trauma tend to collapse, and all that matters is the unlikely connection, the tenderness, that runs between Charles and Lionel.

The line of thought that leads to the novel’s surprising and very beautiful conclusion is undercut throughout the narrative by a countervailing perspective – in which every critical moment, Charles’ teasing of Lionel at the grad school party, Charles’ aggressive pursuit of Lionel following him back to his apartment, Charles’ discussing Lionel with Sophie in the context of their open relationship, is seen as shot through violence, and as accompanied by the understanding that Lionel, in his post-suicide attempt broken state, is not really capable of assuming agency over his own life. I just don’t exactly buy that version – of Charles as predator and Lionel as prey – but Taylor keeps tilting the playing field in the direction of this interpretation by lacing virtually every interaction with really rude, cutting dialogue. “I’m doing your faggy little dance, ease off,” says Charles to his dance instructor. “Your generation is killing this nation with your carelessness,” says a departmental secretary to Lionel when he calls in sick to his exam proctor job. “I felt sorry for my parents because they got me instead of a real kid,” Lionel says to Sophie, to which Sophie responds, “What are you, Pinocchio or something?”

The issue is that people don’t really talk like this – and definitely not in the genteel grad school environment that anchors Filthy Animals. So there’s a very strange cross-cutting of styles through the novel – the narration that’s elegant, detached, interested in beautiful turns-of-phrase and the dialogue, in which everybody talks suddenly as if they’re planning a hit (“I don’t get you” / “What’s to get?” or “We? You can do whatever you want.” / “Ok tough guy”).

The simplest way to deal with this is to say that Taylor just isn’t very good at writing dialogue. But the reason he’s not very good, I’m convinced, is that he believes that there must be an undercurrent of violence in all interaction. The inner narrative arc of Filthy Animals doesn’t tend in that direction, and neither does the bulk of Taylor’s prose, but he seems to feel that a novel should be harsh and loads up the dialogue and selects a title that lead him away from his own artistic instincts.

Effort is made at different moments in Filthy Animals to insist on the structural violence underpinning all of life. It’s not even just the brutal history of America. Dishes “rattle in the sink like thunder.” The early evening sky is “the color of crushed lilacs.” But the truest home of structural violence is, not so surprisingly, American society. And much as Taylor builds his case for the undercurrents of violence running through even the most tender and benign interactions by having his dancer and mathematician characters talk like the cast of The Sopranos, so he creates a sort of fanciful back story to his action – stand-alone short stories that function like Lomaxian folk songs from the American hinterland, the banjo squawking and lovers bashing each other over the head – and these are meant to illuminate the sweet-yet-sour dancers and mathematicians at the elegant graduate school in the big city, to make the case that the garish violence that comprises any folk song lives just as much in genteel urban types but is internalized.

But the issue, again, is that just isn’t what life is like, even in the dilapidated interior. ‘Filthy Animals,’ the keynote story in this volume, is meant to follow a more or less typical night out for a group of teenagers in northern Alabama ‘at the cusp of Appalachia.’ The night features a clandestine handjob between two men, the story of a not-completely-consensual gangbang that occurred a couple of weeks earlier, and then ends, as all such nights must, with racial epithets and a boulder to the back of the head. This isn’t grotesque – it’s meant to be like dirty realism and an explanation of what at least some of the characters in the novel’s frame narrative are carrying with them. Sophie’s Arkansas origins are, for instance, treated as a shorthand for unimaginable suffering. “My parents died. And then my sister, a few years ago, died. Overdose” is her recap of her life pre-grad school. ‘Mass,’ a similarly banjo-accompanied short story tucked into Filthy Animals, features lines like “he felt then that Grigori could have done him any kind of harm without the slightest remorse” and “perhaps it was this way always with brothers, a truce brokered only after an equilibrium of physical strength had been met, as if the potential for physical destruction were the only thing to keep them from tearing each other limb from limb.” To which extravagant hypothesis the right response is um, no, not really. Peace between brothers isn’t usually the result of an underlying dynamic of Mutually Assured Destruction – there’s love involved, and play, and intimate relations aren’t, I humbly submit, the wary standoff between sociopaths that Taylor seems somehow duty-bound to insist that they are.

In large part, then, Filthy Animals is uneven, sensationalist, sort of insincere, but Taylor is talented and when he’s not looking to indict the entirety of the society and of humanity he can write simply and beautifully. “He looked like a high-definition version of himself” is a funny, elegant way to describe a first meeting with an ex who has been hitting the gym and is on a campaign of self-improvement. “The unfussy ease that had seen her through her whole life” is a similarly poised description of a favorite grandmother.

And in one story in this volume – ‘Anne of Cleves’ – Taylor drops the shtick of rural gangbangs and lascivious choreographers and, with mastery, tells the story of a shy woman experiencing her first lesbian relationship. In ‘Anne of Cleves’ there is the same thematic fissure that runs through the other stories in the volume – Sigrid has the power in the relationship, she is better educated, higher class, and more sexually worldly – and there is a degree of exploitation and subliminal violence in convincing wallflower Marta to be her girlfriend. But, in this story, the power dynamics are muted and subtle – they occur most flagrantly in Sigrid’s flashing her high-brow knowledge, which Marta finds off-putting and intimidating. “If this was how dating women was going to be, a series of increasingly esoteric questions, she wasn’t sure she liked it that much either” thinks Marta on her first date with Sigrid, during which Sigrid insists on the parlor game of selecting which wife of Henry VIII Marta is, no matter that Marta has never really heard of Henry VIII. It is cruel and condescending of Sigrid – Marta becomes very attuned to the way that Sigrid treats her when they’re out with friends (“Sigrid would sometimes look back at her with a smile as if she were checking in on a pet”) and, if she doesn’t know much about history, Marta does know that it’s not exactly a compliment to be called Anne of Cleves. But, as it is in the mysteries of love and of human dynamics, that power imbalance isn’t necessarily some condemnation of the relationship as a whole. It turns out that the way Marta’s personality is structured, she likes being subordinate to Sigrid, accompanying her on a work trip, “holding Sigrid’s hand, carrying her bag if she needed it, offering her whatever support she could,” and, coming across Anne of Cleves in a deck of playing cards, she feels a sense of powerful affinity, watching “the faces whip by, a parade of anonymous smiling women, all looking back at her as if across the fanning waves of time.”

This is excellent writing, believable, heartfelt, and free from the moral censoriousness that besets much of Filthy Animals. I am not, however, trying to say that Taylor would be better off avoiding overtly political work, sticking to art for art’s sake, as in ‘Anne of Cleves’ – the kind of simple, realist story that has been running in The New Yorker since time immemorial. In the rest of Filthy Animals, he is dealing with important subject matter – in particular, the through-line between America’s legacy of violence – and, on that theme, the aggression inherent in Charles and Sophie’s sexual advances is interesting and morally complex. But there is a way, in Taylor’s prose and in the orthodoxy of our moment, that these discussions tend to collapse into reductionist strictures. Power imbalances – bad. Sexual encounters within power imbalances – double bad. The art of a novelist is, always, to evade these graven moralities, to follow the winding desires of the human heart wherever they lead. Taylor is capable of doing that – Filthy Animals is full of unexpected, tender romances – but only when he seems to relax internally, to really let himself go.

JUSTIN E. H. SMITH’s The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is (2022)

A real disappointment. Smith has been a polemical MVP over the past year or so, writing strong pieces for Harper’s on the pandemic and for Liberties on the simulation hypothesis - both of them erudite, elegant, impassioned. And, looking at it on the sales table, The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is struck me as being part of a much-needed return to sanity, our collective waking up from our Internet addiction and our delusions of technological progress.

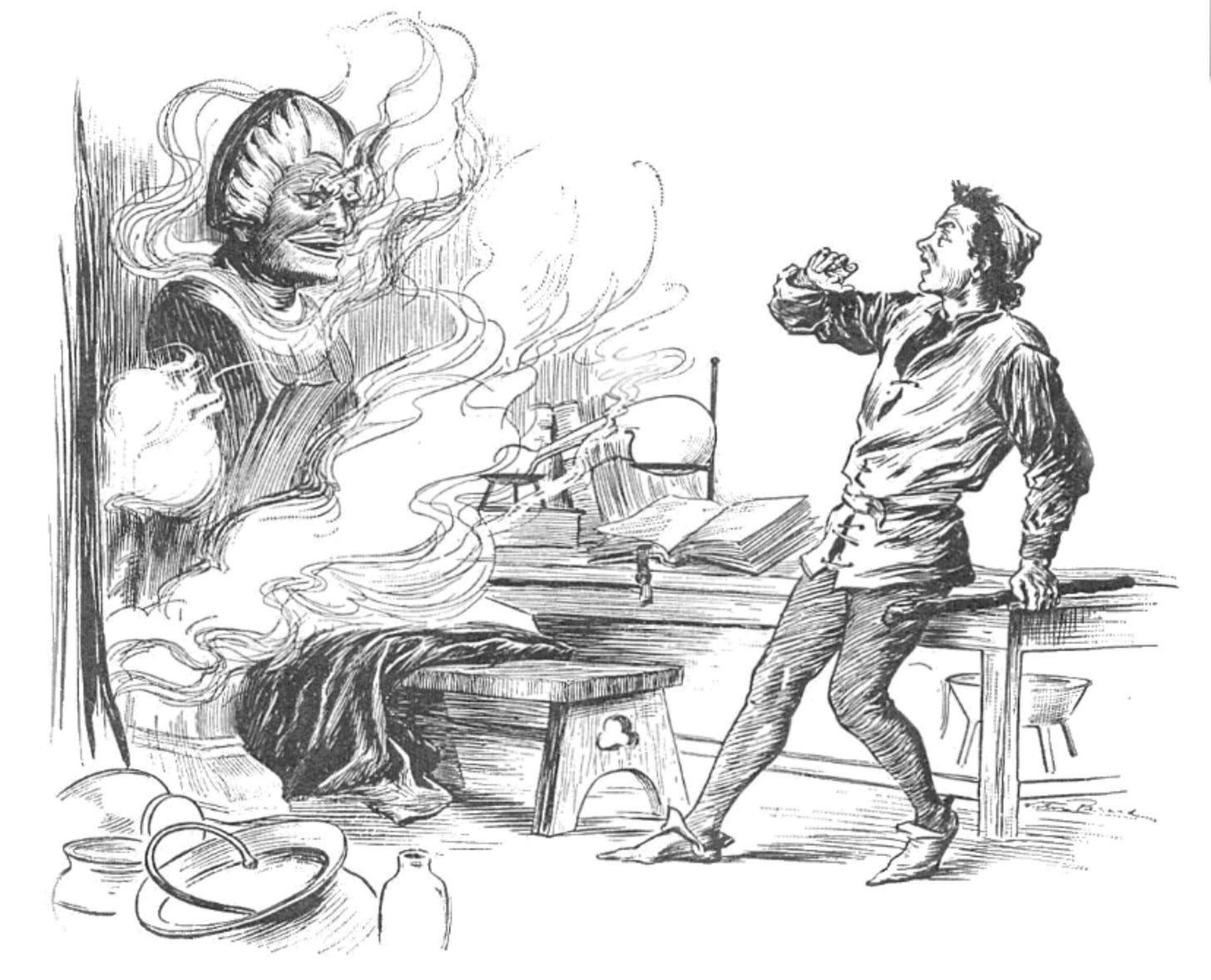

I’m not exactly sure what I was hoping Smith would say, but definitely more than what actually emerges out of The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is, which is basically thesis-less and a classic case of what can go wrong when a writer steps out of their field of expertise. Smith’s overall aim sounds commendable, which is to demystify the Internet, to spring it loose from the chattering incantations of the programmers and the tech titans, to bring the entire enterprise back onto a playing field where it can be dealt with in terms of history and philosophy. To do that, though, Smith takes himself very far afield - farther afield, probably, than is covered in anybody’s expertise - and by his own admission essentially just ends up reading a bunch of Wikipedia articles. The articles turn out to be on such arcane subject matter as neural networks of sperm whales and lima beans, Roger Bacon’s talking head, Leibniz’s belief in the power of calculation, Ada Lovelace’s Analytical Engine, the 19th century scammer Jules Allix’s hoax of snail telepathy, and so on, all of it vaguely interesting, none of it adding up to a coherent theory of the intellectual deep history of the Internet. About midway though the narrative, Smith catches on to what’s going wrong and begins to get concerned about the trajectory of his argument - “we have by now arrived dangerously close to a thicket of metaphors,” he cautions himself at one stage - and at the same time to cook up elaborate justifications for why he’s not able to say more about his chosen topic. And so much of The Internet Is Now What You Think It Is reads like an excuse for itself. Even the epigraph is the less-than-encouraging “This is the struggle with social media: it devours importance” and Smith in the dispiriting final pages makes some wishful comparisons between his loose method and that of Robert Burton (namely, that his browser history bears some resemblance to Burton’s intellectual peregrinations).

Smith is such an intelligent and serious philosopher that I’m tempted to insist that the problems with The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is aren’t so much his fault as a fundamental deficiency of method - i.e. that philosophy itself can’t deal with the sheer strangeness of the Internet. The best he can do is to claim that the underlying concept of the Internet was anticipated by various precursors - not just in human interactions but in the natural world. The Internet, in his reading, comes to be formulated simply as networks, not so different from the “wood wide web,” through which fungi and a wide variety of critters are thought to communicate, and not so different from medieval trading networks. And the critical ideas for the mechanical Internet are yanked away from the usual-suspect founders and ascribed to a charming set of early-modern polymaths, Roger Bacon, Gottfried Leibniz, Ada Lovelace, etc. I’m not quite sure what Smith thinks he’s doing here, but the best guess is that it’s a bit of intellectual proprietorship for the philosophy departments - some thesis that it’s not at all as if the humanities and the traditional sciences have been completely outflanked by a horde of Vitamin D-deficient programmers or that the machine techs have outsmarted the entirety of the intellectual class, that, in fact, the philosophers have had the concept of the Internet well in hand from the very beginning, centuries before the iPhone was a mote in Steve Jobs’ eye, and that, contrary to all appearances, philosophers possess the best tools for understanding the new cybernetic reality. If that is Smith’s thesis - that the Internet is no big deal, that it’s really just a kind of side hobby of Gottfried Leibniz’s - it’s contradicted by a sobering passage that Smith employs to open his narrative. He lists four core disruptions by which the Internet has produced a society different from anything that has existed before - 1.the exploitation of human attention as a natural resource yielding profits; 2.the interference of the Internet with the very faculty of attention; 3.the monopolization of human activity by a single device i.e. the smart phone; 4.the rise of dataism, an all-encompassing philosophy by which human beings understand themselves as data points and are incentivized to ‘gameify’ their existence to be the best possible data point. I have no argument with any one of these points - they seem like a valid philosophically-minded summation of the deep psychic harm that the Internet has done, in creating a social chasm distinct from anything that has ever existed before.

Where I lose Smith is in the murky process by which he weaves back from his stark opening statement to the claim that, actually, the Internet is no big deal, has all sorts of historical roots, and that, therefore, we can adapt to it. Smith himself seems to be much more engaged with his opening than his ending, and my sense is that the argument he really wants to make - the more important argument - emphasizes the chasm between different eras. Essentially, each new technological paradigm produces a rift beyond which human identity is construed completely differently. Agriculture seems to have been one of those rifts - and is memorialized in the myth of the ‘fall’ and the ‘expulsion,’ the turn from the beneficent earth to an earth that demanded toil. Literacy was to a great extent a rift - as memorialized in the legend of the oral storytellers who lost the ability to store complicated tales in their mind at the very time that they learned to write or who broke their instruments in protest at the imposition of literacy. The European technological revolution - the combination of the scientific method and the correspondent ability to produce dehumanizing, invincible weaponry - was another one of those rifts, a decisive turn leading to mechanization and, on the whole, the loss of a simpler, more harmonious way of life. On the level of identity, the invention of photography and film is probably a more dramatic chasm than is usually recognized - a shift from a sense of identity based on human memory to identity based on mechanized mimesis. And computers may well be the most decisive rift of all - with the human capacities of concentration and intelligence clearly outclassed by algorithms and AI. There is no use pretending (and Smith knows this perfectly well) that that shift is anything less than a profound tragedy and a shock to the psyche. And part of the tragedy - and a large part of the reason why we experience anything as tragic - is that we lack the ability to understand or to chronicle the change. The Internet isn’t really a logical extension of Leibniz or Lovelace - its primary form of motion is acceleration and it creates a stratum of reality that’s different even from what the executives of the tech companies might have predicted for their own products - and the only real emotional response to it is in the deep suffering of the fall, the expulsion, the understanding that we have lost a simpler and probably better mode of life and have to make do, as we can, with the new reality. As Smith himself phrases it, “It may be that the loss perpetually, as by an iron law, balances out the gain.”

Where I agree with Smith is that there’s no choice but to adapt - as was the case for the agricultural revolution, the industrial revolution, every other one of the quieter cognitive revolutions with their distinctive psychic imprint - and the computer revolution (which has turned out really to be the neural network revolution) is no different. That’s a somewhat different mindset from The Social Dilemma or from Jaron Lanier, who lean towards a stop-paying-the-electric-bill Ludditism. As Smith more pragmatically puts it, “The present situation is intolerable but there is also no going back.” We will continue for the foreseeable future to be in a sort of post-reality existence in which our attention is ruthlessly divvied up and monetized, our politics goes haywire, and our social engagement becomes a bizarre, rigged video game - and there is nothing, really, that anybody can do about it. It is different from anything that anybody has dealt with before - and the precedents of Roger Bacon’s talking head and scam escargot telepathy aren’t particularly consoling. All that we can do is to be there for each other - through the distorting prism of our devices - and, as much as possible, try to weather the storm.

@Zoe - I think the point is less "should you read or not read" and more like a discussion on the book itself. Filthy Animals sounds so so imho.

Wait, so should I read Filthy Animals or not?

Thanks for these posts. Always absorbing!