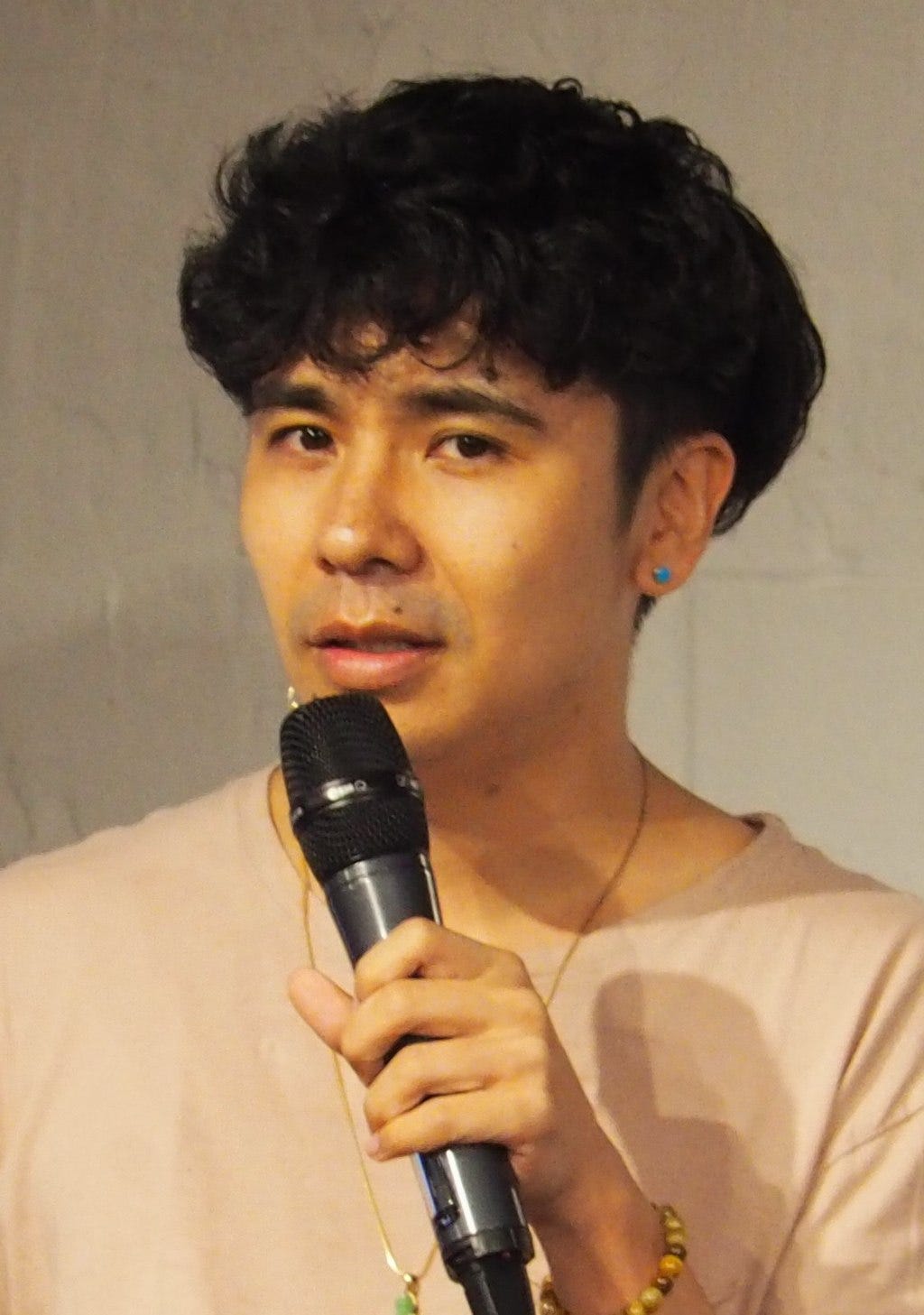

Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (2019)

Sentimental and a hive of cliches but it does have a certain power in it - I can’t completely write it off in the way that, you know, I’m always tempted to write off every popular book.

Still, I suppose we should start off by saying that it’s full of just awful writing. A few samples:

- Because freedom is nothing but the distance between a hunter and his prey

- What is a country but a life sentence

- I am writing from inside a body that used to be yours [a son writing to a mother]

- The human eye is god’s loneliest creation

- Sometimes I imagine the monarchs fleeing not winter but the napalm clouds of your childhood in Vietnam

- I was a boy once and bruiseless

I find all of these sentences to be obviously, absurdly bad, but bad in a way that is symptomatic of wokeness and of some prevalent writing styles at the moment. Vuong – astonishing as it is to say this – is a kind of god for a hip literary crowd. The view is that he has it all, he’s a poet, writes tenderly, with a poet’s sense of rhythm, and is able to deploy the resources of poetry to deal with very difficult, violent experiences – the legacy of Vietnam, the poverty of first-generation immigrants, the tribulations of coming-out in very closed societies. I can just picture the crowd at the reading nodding along, making the ‘ah’ sound, for a line like “What is a country but a life sentence,” which feels both tender and brutal at the same time but when you think about it is nonsense. A life sentence in a prison is a life sentence. Living in a country is a constraint. A rhetorical excess like Vuong’s denudes all meaning from what he is trying to say.

And same goes for all the cringe-fests I’ve quoted above – the mix of attention to the very physical and concrete combined with a poetic flight. To me, ‘sentimentality’ is the perfect word to describe Vuong’s prose and what’s wrong with it – and what’s interesting about this moment in the history of literature is the extent to which critically-minded bookish people are willing to condone overt sentimentality. “Sentimentality is the third rail of American writing,” wrote Nicholson Baker in a piece a few years ago – and, with writers like Vuong and Hanya Yanagihara, that taboo is, for many literary people, absolutely shattered.

The explanation for why this is so rests on cultural faultlines. The idea is that the dour critic, with impeccable good taste, policing for any trace of sentimentality, is a vestige of imperialism – and of Western Europe’s stiff upper lip. In the new, broader church of literature, goes that reasoning, wetter narratives are more acceptable. Various cultures around the world – Vietnamese included – have modes of expression that veer into what a stodgy Western European could be conditioned to see as ‘sentimental.’ And the reality of life-on-the-wrong-side-of-the-tracks-in-America, that reasoning continues – life as an immigrant, or the experience of coming-out, or the experience of addiction – requires, to be truthful to itself, a departure from the strictures of ‘good taste,’ a license to exaggerate, an ability to be irrational or even illogical. (And cue the nodding heads for the absurdic ‘What is a country but a life sentence’.) Within the framework of On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, the justification for the collapse of good taste, which justifies in turn the rampant sentimentality of the prose, is the enormity of the scale of imperial destruction and the nihilism that that generates in the mentality of the novel’s narrator. “Your grandfather is nobody,” the narrator’s grandmother tells him – in other words, the destruction of Vietnam was so complete as to obliterate any system of values, any pride in individual identity.

So, for me, that’s what happening when Ocean Vuong is venerated. There’s a sense that imperial crimes are so vast, modern life so broken, that there’s a need to throw out everything and start all over again. And the place to start is with the immediacy of suffering. Authority is given to those who have suffered in such unspeakable ways that their very inability to communicate is taken to be a sign of their possessing some truth that goes beyond language. Within the narrative of On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous everybody is impressed with the grandmother’s sangfroid when she hears three shots during the Hartford night and announces that that’s nothing – at the peak of the U.S. aerial bombardment, she says, “entire villages would go up before you knew where your balls were.” And the corollary to that is that anybody who speaks too fluidly, who is able, for instance, to declare their love openly, comes under suspicion. “What if the mother tongue is stunted?” Vuong’s narrator, Little Dog, wonders. “The most common English word spoken in the nail salon was sorry,” he writes. The idea is that language itself has been degraded by the traumas of history – English, in its nail salon iteration, becomes a vehicle for reifying structures of dominance and submission. And Vietnamese has been more or less obliterated by the onslaught of American carpet bombing, very much as the grandfather’s identity was obliterated. In that new context, strange linguistic leaps are to be expected – in some cases, a bridge between Vietnamese and English, in other cases far-fetched, not-quite-logical metaphors (the monarch butterflies of Hartford, CT fleeing the napalm clouds of Vietnam) – and actual communication occurs in a subcutaneous, sub-verbal way, above all in acts of service, in the mute-yet-beautiful pragmatic exchange between mother and son.

I am not exactly persuaded by the aesthetic case that Vuong is building here. For me, the traumas of history have nothing to do really with the logical leaps, the explosions of sentimentality that permeate On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, and I can’t help but feeling that to some extent I’m being had, that there’s an element of shlock in the underlying composition of the novel, and – in the way that now everything is ‘porn’; ‘house porn’ and so on – this is poor-childhood-porn, the club for which Édouard Louis is the reigning president, and in which questions of literary merit are subordinated to a debate about who had it worse (growing up gay, an immigrant, with a single mother, and working in the Connecticut tobacco fields from age 14 is, of course, a hard-to-beat entry in that competition).

Still, there is something here. I liked the Trevor section – the way that they’re happy and lonely together. And Vuong’s prose seemed, somehow, to improve in these sections: “He cried skillfully in the dark. The way boys do. The first time we fucked we didn’t fuck at all” and “The force and torque of pain gathered towards a breaking point, a sensation I never imagined was a part of sex.” As a whole, the narrative thread of the novel is strong – the narrator alone with his mother, then alone with Trevor, then coming out to his mother. And it may seem that it’s just one thing on top of another – childhood traumas and beatings, then the pain of being socially ostracized, then the difficulty of coming out, and then the boyfriend overdosing – but, actually, Trevor’s death is handled well, the feeling that there is absolutely no place for a boy like Trevor to go, that, in his world, addiction is completely an inevitability. “The town that holds everything Trevor except Trevor himself” is a beautiful way for the narrator to phrase his desolation – Trevor as a kind of stand-in for a whole doomed way of life and Trevor treated as completely disposable within that world.

Am I just being nice here? Is that section just as much melodrama as everything else in On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous? Well, maybe. The hellscape of the modern American interior is as prone to cliché as the receding memory of the Vietnam War. But I somehow bought it with Trevor, and this is the subtle difference between fiction that’s inhabited and fiction that’s done for effect. The unflinching grandmother indifferent to a mere three shots is a stock figure. The stuckness of the narrator escaping from the Hartford mean streets while everybody he knows – all the Trevors – are overtaken by opioids has the feeling of a genuine terror, Vuong knowing that his writing career, everything good that has happened to him, is a kind of miracle.

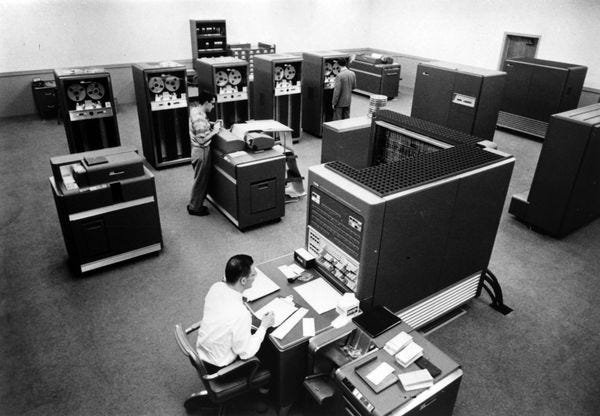

Jill Lepore’s If Then: How The Simulmatics Corporation Invented the Future (2020)

Somehow this is the book that, for awhile, has kept catching my eye on bargain racks. There’s something about it that seems minor and kind of random – a comically-mismanaged company somewhere deep in the 1960s military-industrial complex – and that’s how reviewers have dealt with it, as an intermezzo for Lepore between her explorations of centuries-worth of American history, and Lepore herself is a bit overly apologetic about her subject matter, taking the unusual step for a writer of explaining at some length why her chosen topic both isn’t very important or very unique.

But the story is worth telling – and Lepore seems to spend much of If Then rubbing dust from her eyes with the recognition that the whole thing, the 21st century tech dystopia – the irresistible rise of quantitative reasoning, the assigning of metrics to the entirety of human social life – was worked out by the early 1960s. “Nobody really remember Simulmatics – it had had been too small a player, too weak a company, too clumsy a corporation,” she writes of the errant company that dominates her narrative. “They believed that they had invented the A-bomb of social sciences. They did not anticipate that it would take decades to detonate like a long-buried grenade.” In Simulmatics’ wildly wide-ranging, wildly premature enterprises, she finds the modes of thought that would lead to Facebook, Cambridge Analytica, Palantir, the Metaverse. The reasons that Simulmatics failed were more about poor timing than failure of vision – the technology hadn’t caught up with the Simulmatics vision (after all, it was difficult to bring Facebook to the marketplace when you were thirty years in advance of the World Wide Web) – and it is possible, as per Lepore’s thesis, to understand something about all these later-arriving developments through their petri-dish version in Simulmatics.

The really critical point here is to dismantle the myths of Silicon Valley’s founding in some sort of scruffy anarchist utopia. Long before that, computer technology passed through the government and through the Department of Defense and its many subsidiaries, and those subsidiaries, like Simulmatics, were perfectly capable of envisioning everything that would later be developed by college students in their dorms and were a bit more clear-eyed, right from the very beginning, about the uses to which the technology would be most efficiently put. And so Simulmatics offered up its not-really-developed technology for a truly bewildering array of nefarious purposes, mapping out the electoral populace and coaching candidates on the polarizing strategies that the data suggested; mapping out (with remarkable shoddiness) the behavioral data of Vietnam’s population as a tool for the Defense Department to develop its program of counter-insurgency; encouraging universities to discreetly funnel data collected from private citizens for other purposes into databases that could be shared both with governments and with profit-making corporations; putting the initial pieces together to pursue artificial intelligence. What Simulmatics really represented was – in its most raw, brutal mainframe incarnation - the gospel of predictive analytics, the belief that human beings could be, and through some logical jujitsu must be, reduced to data sets, patterns of past behavior fed through what the Simulmatics engineers themselves called ‘a People Machine,’ yielding both ironclad predictions about the future and fool-proof strategies for mass manipulation.

Lepore is a careful historian and she is a bit hamstrung by her own research – the congenital ineptitude of Simulmatics makes it a frustrating topic, since so few of its initiatives produced meaningful results – but in the moments when she is able to generalize, in a blistering introduction, in her interviews after the book’s release, she makes the compelling case for why it’s the cast of thought embodied within Simulmatics, more than any tangible achievement, that is really troubling. For one thing, the Simulmatics crowd evinced no unconcern whatsoever with the potential misuses of their technology. The story of Simulmatics’ contribution to the Kennedy campaign did, in fact, generate a wave of hand-wringing and widespread concerns that the tech dystopia was nigh, but within the world of Simulmatics the justifications for their brand of tech-generated mass manipulation were readily at hand and almost too plentiful. It could be put to use in the government’s anti-Communist programs (and the breaking-of-the-soul of Ithiel de Sola Pool, who effectively renounced his own parents for the sake of a security clearance, is one of the more breathtaking subplots embedded in If Then – the anti-Communist witch hunts creating a loyal soldier in Pool, who “clung to his anti-Communist credentials all his life, like medals earned on the battlefield”); it could serve the government’s Schmittian progam of retaining order-for-its-own-sake, as in a typically shoddily-executed contract in which, in 1967, Simulmatics attempted to predict the outbreak of race riots so as to help strategize preemptive police activities; it could follow the profit motive, offering itself to a wide array of companies looking to micro-target ad campaigns; or it could justify itself simply through the audacity of its own operations. Ithiel de Sola Pool, shocked at the defection of a fellow social scientist to the anti-war camp, exclaimed, “But Vietnam is the greatest social-science laboratory we’ve ever had!” And, as Lepore writes, “The Simulmatics operated under the proposition that if they collected enough data about enough people and fed it into a machine then everything might one day be predictable.” In other words – the same logic as the Manhattan Project or gain-of-function research. If science made something available, then who was a lowly tech to get in the way of science? (And, incidentally, the lowly techs made profit immensely from their work streamlining the technology, etc, etc.

But the maybe-even-more-concerning aspect of Simulmatics is the lesson learned from its manifold failures – that, in the 1960s, there simply wasn’t enough available data to feed the machine with. The disaffected godfathers of Simulmatics, Pool and Ed Greenfield, turned into lonely prophets of the Internet Age – Pool through an influential 1983 book called Technologies of Freedom, which would become a sort of Bible for Stewart Brand and the open-web absolutists and Greenfield through a somewhat deranged fever dream that he called the ‘Mood Corporation’ and which was an astonishingly vivid prediction of Facebook that he concocted in the early 1980s – and, in some perverse, far-sighted way, they seemed to will into being the World Wide Web and to envision it as a repository of data which would give Simulmaticses of the future the kinds of meaningful data sets that would facilitate high-quality predictive analysis. What the Simulmatics founders had discovered the hard way is the central problem of quantitative reasoning – that it really only works for endeavors with a closed, complete set of data (sports, elections, and to some extent business being easy, the rest of human behavior presenting a challenge of a different order of magnitude). And in their cold, visionary way they sort of crafted the solution – establish a reality that suits quantitative analysis. The internet is that reality, every piece of behavior – purchases, opinions, romantic and family life – generating a digital record which can then be analyzed and exploited.

A ghoulish early indication of that new protocol emerged under fire in Vietnam. The Simulmatics crowd was in the midst of discovering the limitations of their analytical method. The Vietnamese were proving to be very uncooperative for the purposes of the social sciences – language and cultural barriers, as well as the obstacles of armed conflict, inhibiting the collection of reliable data on consumerist preference, which in turn inhibited Simulmatics’ ability to effectively advise McNamara on counter-insurgency – and Pool wrote that an intermediate step of the U.S.’ war effort should be “to somehow compel newly mobilized strata to return to a measure of passivity and defeatism from which they have been recently aroused by the process of modernization.” The internal logic there would really only make sense to somebody in Pool’s position of attempting to reduce a complex society to a series of precise data points – somehow induce passivity and the society can be more effectively mined for its social science metrics. And that same internal logic would promptly be applied domestically in a ‘Mood and Atmosphere’ chart of potentially riotous communities, graded on a scale of ‘Euphoric (Carnival)’ to ‘Calm, restrained,’ and would manifest much more strikingly in the panopticon of the 21st century, in the seven hours-per-day that the average American spends in front of a screen.

The Saigon section notwithstanding, Lepore doesn’t have quite enough of the corporate history of Simulmatics itself to justify an entire book, so she has to pad it out – but it’s an interesting pad! And much of If Then is really a survey course-like tour of the nexus of American political communications and social sciences in the ‘50s and ‘60s. The idea here is that Simulmatics emerged out of a particular strain of technocratic liberalism – which, I’m sorry to say, is tied directly to a self-important arrogance specific to the Democratic Party. The immediate issue at stake was the failure of Adlai Stevenson to move beyond his liberal constituency – and, specifically, to fail to contend with the Republican art of mass marketing. Stevenson, in Lepore’s narrative, functions very much like the Texas Senator Coke Stevenson in Robert Caro’s Means of Ascent, the last stand of an age of dignity and self-restraint. “The belief that the minds of Americans can be manipulated by shows, slogans, and the arts of advertising….is, I think, the ultimate indignity to the democratic process,” Adlai Stevenson said – which, already by 1960, was the quaintest of quaint thoughts. Simulmatics was founded in 1959 in an attempt to inject high-minded liberal principle with a bit of horse sense, which is what Kennedy represented – and the initial advice spat out by Simulmatics would warm the heart of any New England liberal: take a stronger stand on civil rights and take ownership over the ‘Catholic issue.’ But the reasoning that underlay the computer’s advice wasn’t so benign – it was that electoral politics was best managed through micro-targeting of swing demographics and through polarizing stands on attention-getting issues. That was the same reasoning that would be encoded in the ‘Southern Strategy,’ and the smugness of the data-driven method would find its way into the Johnson administration and McNamara’s conduct of the Vietnam War in which human considerations really mattered not at all compared to what was on the computer printout. “The scientists of Simulmatics weren’t villains. They were mid-century liberals….with big ideas and big ideals, big liberal ideals,” Lepore writes. And if that point is somewhat buried in the background of If Then, it’s clearly what’s most soul-churning for Lepore – and something she discusses in her interviews on the book – the sense that the naivete and self-assurance demonstrated by true-believing liberals in the early ‘60s replicated itself in the technological futurists, in the Davos crowd, in the pandemic response, some belief that quantitative reasoning represented a higher order of truth and that institutions, like the intuition-sacrificing sports executives and stockbrokers in a Michael Lewis book, were better off handing over their decisions to the machines (and, implicitly, to the quants who ran the machines).

So, as per Lepore’s half-sketched and I think basically correct thesis, this becomes the way to think about the last half-century. The powers-that-be, governments and the corporations embedded within the governmental structure (the RANDs, etc) were looking to make use of the new tools of mass communication. They couldn’t really get it to work – as in the widespread user dissatisfaction with Simulmatics and the solutions generated by its limited datasets – and so they outsourced the problem to the scruffy Silicon Valley guys, who in the fulness of time, developed a means for harvesting data via personal computing that couldn’t possibly have been generated by a handful of mainframes, and so everything comes full circle, the ‘open web’ creating its back doors to state surveillance and to massive advertising revenue for corporations and the Simulmatics vision manifested in toto.

In an interview for the New York Public Library, Lepore lets herself go in a way that she can’t really in If Then and says, “The thing that kills me is how the cult of these Silicon Valley entrepreneurs relies on the myth of their originality and it’s like man, this guy [Ed Greenfield] is wandering the streets of New York coming up with the business model for Facebook in 1983.” She continues, “Providing a history for a realm in American life that insists it has no history seems to me quite an urgent project – that’s why I wrote the book.” And so the strangeness and unclassifiability of If Then – the quality that made most reviewers scratch their heads over it - is its great strength: the ability of the historians and the humanities-types to finally get a handle on the tech revolution, to move it outside of Silicon Valley la-la-land and back to the realm of political history, in which it’s possible to trace the clear intellectual throughline by which the nasty deferred dream of a bunch of flannel-suited technocrats in the early ’60s materializes itself in what Lepore calls “the data-mad and near-totalitarian 21st century.”

Yeah, what's really shocking is to read Dwight Garner on Ocean Vuong - https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/27/books/review-on-earth-were-briefly-gorgeous-ocean-vuong.html

He has a very similar list of terrible sentences as you have and then he concludes that it basically doesn't matter. Vuong is for some reason beyond reproach. But you have a bit of Garnerism as well! Too much credit to Vuong. And for that matter too much credit to Lepore whose critique could be far more incisive.

So much every week! Crazy! Keep it up