Dear Friends,

I’m sharing a couple of reviews/discussions of recent non-fiction books. For an excerpt of Technofeudalism, see here. At the partner site

, writes on the brass tacks of writer economics.Best,

Sam

YANIS VAROUFAKIS’ Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism (2023)

This is an interesting, substantial book.

Varoufakis is one of these unicorns of the global intellectual space — an avowedly Marxist, former Finance Minister of Greece, who is able to write fluently and non-dogmatically (often for slightly right-leaning websites) and to reach original, unexpected conclusions. I always kind of perk up whenever I see a piece of his, and it’s nice to engage with him in a fuller way.

The argument of Technofeudalism is that capitalism — believe it or not — is sort of getting to the end of its lifespan and is being replaced by another system, which Varoufakis variously labels ‘cloud capitalism’ or ‘technofeudalism.’ Products and markets — the engines of capitalism — have become secondary to another economic system in which monopolistic tech companies have control over online spaces and then charge rent for access to them.

The near-ubiquitous use of the word ‘fiefdom’ in talking about online spaces is more accurate even than we tend to realize. If capital’s ascendance over the agricultural feudal system was based, first of all, on enclosures, we are undergoing a parallel transformation — with vital online commercial space taken over by major tech companies in a series of new enclosures and then rent extracted from everyone who uses them. Varoufakis writes:

We have seen how with the enclosure of the internet commons, cloud capital arose, and how it differs from other kinds of capital in its ability to reproduce itself at no expense to its owner, turning all of us into cloud serfs. We have seen how with the shift online, Amazon now operates as a cloud fief, with traditional business paying Jeff Bezos to operate as his vassals.

Varoufakis is at pains to emphasize that it’s not as if one system utterly supplants the other. The idea is that, as capital was parasitic on the feudal agricultural system (the feudal system produced the goods — i.e. food — needed to survive, but capital introduced a new and distinct source of wealth), so technofeudalism is parasitic on capitalism. Products, and capitalist activity, are there, but the real source of wealth is this rent extraction in online space — with the tech lords needing, once their systems are set up, barely to lift a finger anymore than feudal lords could rely on the serfs passing their rents up the hierarchical chain.

Varoufakis makes such a point of emphasizing these differences of terms most of all as a sort of coalition-building. He is a man of the left but wishes to save the left from its ever-losing battle against capitalism by focusing on a new and even more malignant form of capital — the internet “which killed capitalism but replaced it with something far worse” — and, on the other hand, he creates cover in discussion with avowed capitalists by arguing that the current iteration of ‘cloud capital’ isn’t capitalism at all but is its parasite. It’s an ingenious the-enemy-of-my-enemy-is-my-friend bit of political strategizing and a healthy way of dealing with the new leviathan. The tech platforms are viewed — not as they are now — as a peculiar 21st century manifestation of business-as-usual and instead as the negation of ordinary capitalism. The onus is placed on governments to establish regulatory regimes, to break the hold of the tech giants, and at the very least to eliminate their rent-holding monopolies and encourage more widespread competition. And one step before that is that liberals are encouraged to retrain their sights from their old adversary — overzealous governments — towards a more crucial foe, giant corporations, and to allow government to carry out its exercise of power. “Is it not delectably shocking how, in the end, a global superhighway to serfdom has been constructed not because Western states were too powerful but because they were too weak?” Varoufakis writes.

Varoufakis is one of these people who’s a little too smart for his own good, and he can’t help himself but take a survey through a great deal of 20th and 21st century financial history — all of it interesting, not all of it so germane to his overall point. The history he tells is of the establishment of the Bretton Woods system in the aftermath of World War II, of the United States creating a global currency union, based on fixed exchange rates to the American dollar. The US unilaterally pulled out of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, with the “Nixon Shock,” engendering what Varoufakis calls “a new and truly dismal phase in capitalism’s evolution.” Now, European and Japanese currency were unanchored to fixed exchange but nonetheless the dollar emerged as “the only safe harbor courtesy of its exorbitant privilege” — with international business continuing to be conducted in dollars and with all roads loading back to Wall Street.

Varoufakis calls this the “Global Minotaur” phase of capitalism. It was neatly encapsulated in Paul Volcker’s line from 1978 that “a controlled disintegration in the world economy is a legitimate objective for the 1980s.” That meant, as Varoufakis writes, the replacement of “the most stable globalist system ever” with “the most unstable international system possible, founded on ceaselessly ballooning deficits, debts and gambles.”

Critical to it was what Varoufakis calls “the dark deal” — the United States via its trade deficit keeping demand for Chinese products high while China reinvested its profits in American finance, insurance, and real estate sectors. That deal floated elites in both China and the US but at the expense of ordinary people in both countries — with the US manufacturing sector hollowed out and with China undergoing the Dickensian pains of overinvestment and a rapid-fire industrial revolution — and, meanwhile, with the Global South finding itself short on dollars and borrowing constantly from Wall Street with the IMF as enforcers of the debt.

Of its period of ascendancy, Varoufakis writes, “Our Minotaur will, in the end, be remembered as a sad, boisterous beast whose thirty-year reign created, and then destroyed, the illusion that capitalism can be stable, greed a virtue and finance productive.”

But, for Varoufakis, the real crime of the Minotaur was in finally neglecting capitalism altogether. The twin shocks of the 2008 recession and the 2020 pandemic resulted in a system in which companies and banks no longer invested in products but rather bought back their own shares, inflating their stock prices.

Varoufakis describes a dramatic moment in which he stared at his computer during the 2020 pandemic and, upon seeing that the London Stock Exchange had jumped by 2.3% in response to the news of the UK’s national income falling by 20%, announced to his father, “The age of cloud capital has just begun. The world of money has finally decoupled from the capitalist world.”

What that meant was that the old minotaurs were replaced by a new leviathan — the world of money that no longer connected to anything recognizably capitalist; and then a world of tech, handsomely supported by Wall Street, that carved out its new technofeudal space, charging rents, accepting content-delivered-for-free by regular people, and producing nothing of value itself.

For Varoufakis, there is a blessing-in-disguise somewhere in this. The turn from capitalism to the new system at least means the end of the uphill fight against capital and opportunities for individuals and communities to fight for their freedoms on new terms. Although, as Varoufakis writes, “How likely is it that we take advantage of it? I am damned if I know.” As usual, though, the framing helps. There is no need to be complacent about existing inequalities or existing economic systems. The economic systems themselves are changing more dramatically than we probably realize. That means that we — and we do get say in this — are able to articulate what we really want.

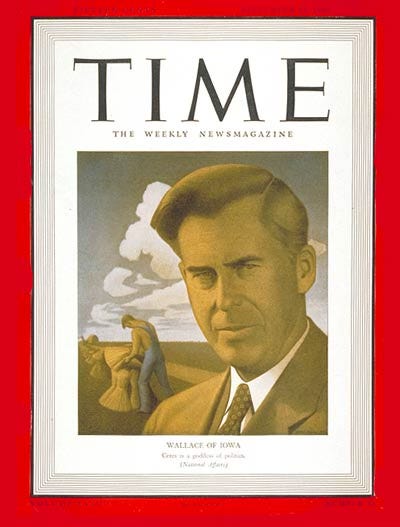

BENN STEIL’s The World That Wasn’t: Henry Wallace and the Fate of the American Century (2024)

It is very rare to read to a 500-page, meticulously detailed biography of a long-forgotten figure, in which the author so openly and utterly detests his subject.

The answer to why that has happened here is to be found in the opening lines of the acknowledgments, in which Benn Steil gives full credit to John Lewis Gaddis for the book. Gaddis, the preeminent ‘realpolitik’ scholar of the Cold War, has been running a sort of rearguard action, protecting American 20th century foreign policy from left-wing critique, and this biography of Henry Wallace is clearly part of that effort.

Wallace represents one of the most fascinating what-ifs in American history — a genuinely progressive figure coming achingly close to the presidency and exactly at the moment when the American ‘security state’ and post-war imperialism could, conceivably, have gone in a completely different direction. He was a highly unlikely figure to have ended up as Vice President and could be understood as part of the New Deal euphoria — a plant geneticist who had become Secretary of Agriculture at the right time and who presided over the Agriculture Adjustment Act, turning into the nation’s farm sector “overnight into a federal protectorate,” as Steil puts it. Roosevelt liked Wallace and in 1940 preferred him on the ticket to the reactionary John Nance Gardner, but, by 1944, when the stakes of the vice presidency had heightened, Wallace was clearly an odd fit to run one of the greatest war machines in the history of the world.

David McCullough describes him as “too intellectual, a mystic who spoke Russian and played with a boomerang and reportedly consulted with the spirit of a dead Sioux Indian chief....When not presiding over the Senate, he would often shut himself in his office and study Spanish.” He was close to a pacifist, highly critical of British imperialism, openly supportive of the Soviet Union, and had been a believing Theosophist — in the 1930s, while in the Cabinet, he was, in a word, part of a cult surrounding the Russian painter Nicholas Roerich, his wife Helena, and their ‘hidden master’ Morya, and a set of highly embarrassing letters were surfacing in tranches in which Wallace wrote to the Roerichs as “Guru,” they wrote to him as “Galahad,” and in which he endeavored to tilt American foreign policy in Morya’s preferred directions, above all towards friendlier relations with Japan. “May the Glory of the flaming Chalices shine even as the Star of the Hero,” was a somewhat typical line from his letters to the Roerichs.

But Wallace was also, literally, seconds away from becoming president. In 1944, he was popular, had widespread support with liberals and the unions, and although a crowd of advisers close to Roosevelt was determined to junk Wallace, Roosevelt seemed to be only half-persuaded. As a member of Roosevelt’s White House staff put it, Roosevelt “never pursued a more Byzantine course than in his handling of [his likely succession.” There was a smoke-filled room — or at least a meeting on a muggy summer evening in which everyone wore shirtsleeves — and the party bosses persuaded Roosevelt to indicate his support for Truman instead. But it was still up to the Democratic convention to decide — and with Roosevelt keeping himself notably aloof. The unions organized a stampede of support for Wallace. With the convention hall deafening in support of Wallace, a liberal Senator, Claude Pepper, sprinted to the stage to place Wallace’s name in nomination and to call for a vote on the spot. But the convention chairman, acting on behalf of the junk-Wallace cabal, pretended not to see Pepper and adjourned for the day. By the next day, the party bosses had a tighter hold over the convention’s gates and were able to choreograph Truman’s nomination.

That maneuver turned out — as party insiders well knew — to have seismic consequences. Roosevelt’s doctor had given him less than a year to live — a prognosis that was to prove accurate. Had Wallace rather than Truman succeeded Roosevelt in early 1945, it’s still likely that the atomic bomb would have been dropped — Wallace would not have had the authority to so drastically change US military policy — but almost everything else would have been different. The US military buildup in the late 1940s would not have occurred, nor would the Truman Doctrine or the Marshall Plan or the doctrine of “containment.” For Oliver Stone and critics of American empire, a Wallace presidency would, simply, have meant no Cold War. The rhetoric from the White House would have been utterly different, with Wallace stressing a vision of “economic democracy” that he believed united the “common man” between the US and USSR.

It’s Stone’s starry-eyed vision that Steil is most eager to disprove. His argument is that Wallace — “too innocent and idealistic for this world,” as Roald Dahl put it at the time — simply failed to see that the Soviet Union wasn’t interested in economic democracy or world peace and that Stalin was bent on an expansionist course regardless of any gestures of goodwill that the US extended towards him. Wallace himself drastically reversed course when North Korea, with Soviet support, invaded the South in 1950 and he became something of a standard-issue Cold War warrior. In later life, he himself seemed to recognize the limits either to his vision or to his ability to execute it. “I was done a very great favor when I was not named in ’44,” he later said.

But that second-guessing would come afterwards. Had he become president in 1945 — likely taking office with a wave of popularity, just as Truman did — he would have had a free hand to push any number of policies extending on the New Deal and on the period of post-war goodwill. America has “always been a progressive country underneath,” he would say in an interview, and that meant stakeholder boards in “basic industries” and nationalization of “scarcity-driven” industries, such as coal and railways. In foreign policy, that would have meant a profound step back from overseas intervention: “the United States has no business in the political affairs of Eastern Europe,” Wallace would say in a speech in 1946, in direct opposition to the policies of the Truman administration in which he served as Secretary of Commerce. That would have meant an attempt to reposition the geopolitical axis of the world, away from the British, whom Wallace disliked — he criticized those in the Truman administration who were “trying to build an Anglo-Saxon bloc that is decidedly hostile towards the Slavic world” — and towards the Soviet Union, which Wallace credited for doing the bulk of the fighting in World War II and which he found to be more philosophically simpatico. “There are only two great powers in the world, the USSR and the USA, and the well-being and fate of all mankind is dependent on good relations between them,” he said in a 1945 meeting with Soviet official Anatoly Gromov.

All of this is, to say the least, intriguing. Wallace was certainly right that the Truman administration marked, in economic terms, a repudiation of much of the New Deal. It’s not unimaginable that Wallace, pushing from the left wing of the Democratic Party, could have instituted a sort of stakeholder capitalism in the US that would have withstood the Friedmanian shareholder capitalism that was to come. It’s in foreign policy that the implications of a Wallace presidency are even more dizzying. Had he maintained control over his administration, Wallace would have reversed the interventionist tendencies of Roosevelt: he certainly would not have opposed the Soviet Blockade of Berlin. He might well have allowed West Germany to fall under the Soviet sphere of influence. And the US military might not have been in position to oppose the North Korean invasion of 1950. Steil takes it for granted that a Wallace presidency would not actually have resulted in greater harmony between the US and the Communist world. It would have meant a “delayed Cold War” with the US in a far weaker position to oppose advances by the Communist Bloc. But another interpretation is possible — that the US would not have been pulled into far-flung alliances at the outermost limit of its military power. No intervention in Korea likely would have meant no intervention in Vietnam. The US military establishment was unlikely to roll over completely, Wallace or no, but it’s possible that the Wallace administration would have — at the expense of Berlin, South Korea, South Vietnam, maybe Iran — achieved a more manageable defensive line.

Some of that analysis turns, though, on what one makes of Wallace, and Steil, really, has nothing good to say about him. To Steil, he was self-important, pompous, arrogant; (“he was only interested in two topics, plant genetics and himself”), insincere in his idealism (“he loved humankind but was mostly vexed or bored by humans”); a habitual backstabber (Roosevelt finally turned on him over his incessant in-fighting for control of the Bureau of Economic Warfare); utterly credulous in his attitude towards Stalin (not only was he feeding Gromov, a KGB operative, high-level intelligence but he seems to have allowed Stalin personally to edit an important public address of his); a dilettante in his work ethic; and an undertipper.

Steil’s thesis is that the US dodged a major bullet when the 1944 Democratic convention chair averted his eyes from the charging Claude Pepper, and, given Wallace’s abundant character failings, it’s a bit hard to argue with Steil. But the contrafactual with Wallace is deeper than that. It’s about whether the US could at some point have gone in a progressive or, let’s say, social democratic direction. Wallace, for a brief moment, offered an inside track to that route, which never really materialized again in presidential politics. For those on the left, there is much to take heart from in Wallace. It really could have happened. Actually, it wasn’t more than a few seconds away.

Oh, and here I thought that "neofeudalizm with smartphones" is my invention))

Very interesting article, Sam; I also would like to "steal" “he loved humankind but was mostly vexed or bored by humans”-happens all too often.

Thanks Sam. I'd like to read the techno feudalism book. It is an interesting way of looking at the economic world today. I wonder if he addresses the "creative destruction" of Schumpeter. It has been the case throughout history that most sectors in capitalism have their time as seemingly unstoppable juggernauts and then a decade later things change. I'm thinking in terms of income and wealth.