SIGRID NUNEZ’s What Are You Going Through (2020)

Everybody seems to be discovering Nunez at the same time. Which is a little odd – she’s been a productive, serious novelist for decades. But no matter. In her 70s, she’s having her moment, and there’s a quiet consensus, I think, among everybody who reviews her that she’s among a very small handful of contemporary writers who actually matter, who know their way around human psychology and who are playing for keeps. John Banville, Jhumpa Lahiri, J.M. Coetzee are in that category – which threads back to the high style of the Western literary tradition, to Milan Kundera, Doris Lessing, Czeslaw Milosz, Jens Peter Jacobsen, etc, a bracing pessimism, an understanding that there can be no higher truth than individual experience and that individual experience is not merely tragic but also shameful, humiliating.

An initial impression of Nunez is that there is something anachronistic about her – not only because her style is patrician and out of keeping with the sociological idealism that underpins virtually everything being published at the moment but also because she is so firmly committed to realism, to an evident belief that literature doesn’t really have the luxury of branching off into the fantastical and that its highest purpose is to take the bleak tour of the human psyche. The reigning cool style holds it as a given that realism has been dispensed with – sort of in the way that modern art decreed that representational art had hit a terminal point beyond which it was no longer interesting – and Nunez, throughout What Are You Going Through, argues vociferously against that perspective. Anybody who dismisses realism prematurely, she seems to be saying, needs to deal with all the corners of the human experience that were left out in the period of realism’s ascendence – needs to deal, for instance, with the particular experience of aging as a woman, the ‘bad dream’ of facing old age poor, lonely, unattractive, with fraying attachments, surrounded by saccharine bromides of how one is supposed to behave, and suffused with too much shame to tell the truth of things. It’s interesting to me that the two best novels I’ve read recently – Lahiri’s Whereabouts and What Are You Going Through – deal with the same topic, the moment in which a middle-aged woman realizes that the bridges are burned and that the trajectory of her life heads in one direction only. Lahiri’s narrative strategy is elliptical – and there is a sense that she herself has difficulty looking her subject squarely in the face. Nunez, on the other hand, has no such hang-ups. She seems to be challenging herself to see how bleak she can get – opening with the anti-natalist, we-are-irretrievably-doomed speech of the narrator’s ex and upping the ante from there, dismissing one by one the consolations of art, of religion, of love, even of grace itself.

That somewhat adolescent determination to be as mordant as possible makes What Are You Going Through a bit claustrophobic and overdetermined. Early on, the narrator sets herself up in competition not only with her ex but with Ford Madox Ford – as if in contempt for Ford’s conceit that the tale of the sexual adventures of Edward Ashburnham could possibly be ‘the saddest story’ that he had ever heard. Nunez dedicates the novel’s opening to proposing contenders for stories that are much sadder than that. There are various dramatic sad stories, the tale of the lonely professor who finally found happiness in an affair with a younger man, only to discover that the man was his long-lost son, the tale of Leonora Carrington who could never be with Lytton Strachey in life but shot herself in the stomach so as to mimic his stomach cancer and to be with him in death, the tale in the mystery novel that the narrator intermittently reads of the woman with the undying love for a serial killer boyfriend – but these are understood to be melodramatic escapism from the real sorrows, just as the narrator and her friend come to view the anti-natalist speech of the narrator’s ex as a kind of self-important practical joke. “It’s nice to see he’s his old ball of fun self,” says the friend, who never liked him anyway. The real sorrows are much more trenchant and embarrassing. There’s the tale of the woman at the gym who is very pretty and seems to have chosen to be as vapid as possible as her strategy for evading life’s hardships, and then simply cannot endure what age does to her looks – can’t enjoy shopping anymore, can’t bear to be looked at. “There was genuine horror in the woman’s voice. There was horror and pain and bitterness. What a nasty trick life had played on her,” the narrator writes. Then there’s the tale of the friend’s hopeless relationship with her daughter – the friend pouring every bit of her broken self into raising the daughter and the daughter being almost perfectly ungrateful, dedicated solely to the memory of a father who had left before she was born. “This much-loved, much-wanted child who grew up with every conceivable privilege in a world full of suffering and here she is acting like an orphan, a refugee, a goddamn boat person,” says the friend. There is the tale of the friend herself, who seems to be steeled for the end, who has her books, her writing, her terrific sense of humor, and finds herself not just overpowered by her cancer but bored by it, incapable of finding anything interesting to say on the subject, and fixated single-mindedly on her clandestine euthanasia.

And up goes the ante. The very pleasant, virtually ideal lifelong relationship between the narrator and her friend is deployed – courtesy of its unruffled ease – as an aid to euthanasia, the narrator the one person whom the friend can really trust to be a companion to the end. The prospect of imminent death serves not to heal the relationship between the friend and her daughter but only to make the rupture irreparable – the friend deciding that she cannot trust the daughter even with the knowledge of what’s to happen. The prurient desire to see the euthanasia as some sort of ennobling exercise – some proof of willpower – is quickly dismissed by the friend. “Why should cancer be some kind of test of a person’s mettle?” she asks. The trio of characters – narrator, friend, and ex, all of whom have dedicated their lives to art – find, in the end, art to be completely useless and the only honest approach to take to the truth of things is a kind of irritated contempt. “For decades it was art and culture he’d gone around the world lecturing about,” the narrator remarks of her ex. “How could he have lost interest so completely?” And each of the characters swiftly finds their attempts to read, to journal, to extract meaning, to fall flat.

There is a nasty paradox in here. Literature, in Nunez’s school of thought, is seen to be an extension of intelligence – and to be at its best when steely and uncompromising. The inevitable belief following from that proposition is that the only true subject of literature is death – and a work of art graded according to its ability to deal unflinchingly with death; or, more specifically, with what Jacobsen called “the difficult death,” atheistic death without possibility of redemption. But get to that place of nihilistic exactitude and meaning falls away completely. And Nunez seems to be aware of that paradox. The feeling is like the kid’s game in which you put hand over hand on top of one another, the tension building inexorably, until you just lose your balance and the whole structure topples into absurdity. And something similar happens in What Are You Going Through, Nunez bidding with herself to write the ‘saddest story’ anybody has ever heard, the tale of aging and the parting-of-ways with one’s loved ones, followed by the tale of the two old friends supporting each other through euthanasia, followed by the tale of minor betrayals as the euthanasia drags on and turns anti-climactic, the tension become excruciating until the house is ruined by an overflowing bathtub and the friend forgets about the whole thing. Nunez, I think, means to make the story even worse in the novel’s concluding section – the tale of how the two friends gradually fall out of touch, become more distant, not closer, as a result of their shared experience – but her heart goes out of it. The feeling is of Simon Stimson railing, plausibly enough, against existence in the graveyard scene of Our Town, and another of his cemetery mates replying mildly, “Simon Stimson, that ain’t the whole truth and you know it.”

That’s where What Are You Going Through seems to end up – pulling its punches; not quite the splenetic masterpiece that Nunez had in mind – but, still, so bitter, such a challenge to any sentimental efforts to soften the realities of age and death. There’s a grim parable towards the end that really stays with me and encapsulates the novel’s acerbic power – its assault on the very idea of solidarity through art; and its view of life that, once you think you’ve hit rock bottom, then the trap door opens up.

The parable connects to an early essay written by the narrator’s ex – when he was his ‘old ball of fun self’ and had not yet set his course by anti-natalism – and in which he explains that the Tower of Babel story had been underestimated for its savage misanthropy. It was not merely, the ex postulated, that God had split the world into different tribes incapable of understanding one another.

“God had in fact gone ever further,” the essay runs. “It was not just to different tribes but to each individual human being that a separate language was given, unique as fingerprints. And, step two, to make life among humans even more strifeful and confounding, he beclouded their perception of this. So that while we might understand that there are many people speaking different languages, we are fooled into thinking everyone in our own tribe speaks the same language we do.”

The narrator is taken by the essay but attempts to talk her partner out of this bleak perspective.

“’Even people in love?’ I asked, smilingly, teasingly, hopefully. This was at the very beginning of our relationship. He only smiled back. But years later, at the bitter end, came the bitter answer: People in love most of all.”

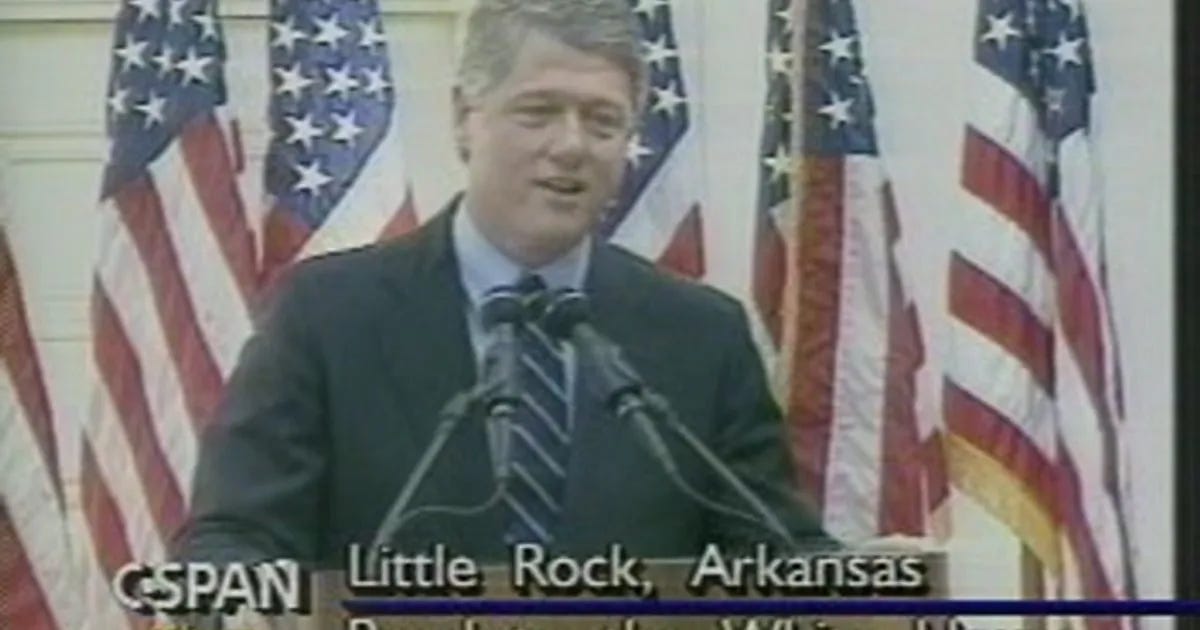

JEFFREY TOOBIN, A Vast Conspiracy (2000/2020)

I was getting on an airplane and wanted to read something that wouldn’t make me think too much. So: mission accomplished. This was the perfect book for that task. It was fast, fun, wonderfully readable, and, in a sneaky way, important. The Clinton-Lewinsky scandal seemed like the height of triviality and, in a way, the peak of an era of good feelings. If this is what we’re worried about, went an undercurrent of sentiment, then we must really be doing fine. But there was some odd sense of foreboding about the scandal, like it was a metaphor for something that nobody could quite put their finger on - and Toobin, with very delicate writing, teases that out, these evocative scenes, Congressman Boucher breaking down and crying on his morning run, Congressman Gephardt suddenly delivering this ringing oration from the House Floor about the disappearance of dignity from American life. And these moments, apparently out of all proportion to partisan debates about blowjobs, do actually have a terrible, almost classical resonance to them - the feeling that this period was the acme of democracy and that it started to slide downhill from there.

I somehow expected that the book would be more about party politics - about people like Ann Coulter and the young Brett Kavanaugh - and that the episode would be treated as more of a sting operation to get Clinton. But, as Toobin writes, “The anti-Clinton efforts….were not centrally coordinated. Many of the participants in Mrs. Clinton’s ‘conspiracy’ did not know each other. As for ‘vast,’ the central players in the effort to bring down Clinton could probably all have fit in a single school bus.” So much for the vast right-wing conspiracy. And, as for Republican expectations that ‘the other shoe would drop,’ that the Lewinsky revelations would lead to some other greater scandal, that never even came close to happening. “The case was never anything more than it appeared to be,” Toobin writes convincingly, “that of a humiliated middle-aged husband who lied when he was caught having an affair with a young woman from his office.”

And that was what the American public always intuited about the scandal - much more so than the Washington insiders. That, ultimately, it was a tempest in a teapot and not really a political issue – and that became the lasting impression of the scandal, that the American public wasn’t really put off by Clinton’s behavior and refused to punish the in flagrante president or his party, while the conservative Republicans, and the more god-fearing the more prurient, turned out to be the ones obsessed with all the dirty details.

But it was a big deal. And so much of what we’re complaining about at the moment – hyper-partisanship; the capture of politics by a tabloid mentality – really dates to this time. There seem – from thinking about Toobin’s book – to be three smart ways to conceptualize the scandal.

One is that it symbolized the moment when politics really became an extension of the legal system. Toobin is a legal reporter and, not surprisingly, this is his focus. In that construction the Clinton case becomes a peculiar sort of karma for activist Democratic lawyers, the Clintons among them, who believed in seeking reform through the judicial system, with lawsuits and particularly sexual harassment law as an instrument. It was inevitable, writes Toobin, that sooner or later the other side would make use of the same set of weapons. In his depiction of the story, the case has a runaway train feel to it. Once the Paula Jones suit was filed, the only real way to stop it would have been for the Clinton side to settle – and Clinton was never really willing to do that given the potential political repercussions. And as much as Susan Wright, the presiding judge on the Jones case, would have liked to have excluded the rundown of Clinton’s sexual behavior as admissible evidence, she was constrained by the Violence Against Women Act – which Bill Clinton himself had helped to push through Congress – and was obligated to allow the plaintiff’s lawyers to call witnesses testifying to Clinton’s behavior during other affairs. And once Clinton’s perjured deposition found its way to the Office of the Independent Counsel the rest of the story seemed somehow foreordained – the litigiously-minded Starr team was going to pursue the case and the House Republicans were going to run with it and then impeachment by the House and acquittal by the Senate followed logically enough from there. The usual elegy on the Lewinsky scandal is that this was the moment when the public-private divide broke down and the private lives of public figures became completely fair game for prying journalists. I’ve always found this to be a less-than-satisfying verdict. Politics had been shaken by sex scandals in the past – the Macmillan government in Britain fell, really, for less than what was at stake in Clinton-Lewinsky – and Bush, Obama, and in a weird way Trump managed to replace the veil over their private lives. Toobin’s analysis is more subtle. It’s not so much that the press refrained from covering dirty political gossip over a gentleman’s agreement; the press was always looking for opportunities to cover stories like the Clinton-Lewinsky affair. But there was no excuse to do so when politics had the pretense of being high-minded and politicians mere representatives of the popular will. Once the logic of lawsuits had taken hold, that division broke down. Everybody was sueable and subpoenable and there was now an available excuse – the ‘character’ question – that allowed the press to declare open season on politicians’ private lives.

The other smart way to think about Clinton-Lewinsky is as a watershed in questions of sexual consent. The sudden patriarchalism of Democrats in the midst of the scandal – the knowing acknowledgment that, of course, men in power are going to have affairs; that a person’s sexual life is their business – belied a much larger trend leading to the case and continuing long after it. The implication of sexual harassment law held that any workplace sexual contact involving a power imbalance constituted, in one way or another, harassment. In a sense Clinton was very lucky to have had the scandal when he did – ten or, certainly, twenty years later there would have been much more discussion about the implicit coercion in his sexual encounters with Lewinsky, her disavowals on that subject notwithstanding, and it would have been much more likely that the Democratic base would have stampeded away from him. The most interesting section in A Vast Conspiracy is actually a digression into sexual harassment law – and a discussion of how, by the late 1990s, it had become clear that consent was no longer a sufficient defense. “The distinction that Clinton emphasized so strongly in his grand jury testimony – that he had engaged in consensual sex, not sexual harassment – scarcely even existed under the law relevant to his case,” writes Toobin. The irony was lost on almost no one that, when faced with the Lewinsky scandal, so many rock-ribbed Republican men suddenly became staunch advocates of sexual harassment law, but Toobin claims that, seen in a certain light, this wasn’t so surprising. “In one critical respect two of the great social movements of the late twentieth century, feminism and the Christian right….pushed the country in precisely the same direction, toward the idea that the private lives of public people mattered as much as their stands on issues,” Toobin writes. And on the issue of sex-in-the-workplace by a public figure, the two strands converged – feminists writing the laws mixing the public and private which were then deployed by evangelical Republicans eager to militate on questions of ‘character.’ And that hint of harassment, or at least coercion, became the glue that kept the case alive for as long as it did. It was never enough, in the sexual climate that had developed by the late ’90s, to say just that a person’s sex life is their business. Sexuality – even apparently trivial workplace incidents – had become fair game for the legal system, which meant that they were fair game for the media and for public discourse. And that resulted in the utterly weird puritanism that has so bewildered people from anywhere else in the world when trying to understand the sex lives of Americans – on the one hand, an open display of sexuality, as in Lewinsky’s feather-plumed Vanity Fair shoot; and, on the other hand, intense public scrutinization and censoriousness for any actually-occurring sexual encounters.

The third ‘smart’ way to think about the scandal is a little more woozy and mystical. The unnerving sense of it is that it revealed a ground truth about democracy – the sort of thing that made the Greeks and Poles and everybody who had experimented with democracy conclude that, eh, it doesn’t really work and that sooner or later it degenerates into a spectacle exactly like Clinton-Lewinsky, the halls of power gummed up by tawdry details of regular people. And the people involved with the case – and Toobin really has a novelist’s eye about this – invariably turn out, on deeper inspection, to be very moving. Essentially, they were all stuck, one way or another, and were aspirational – seeing, somewhere in the swirling matrix of the Lewinsky scandal, a payday, however unlikely, for themselves. As Toobin writes of Paula Jones, “Until the moment she took on Bill Clinton, her life was mostly sad, mostly ordinary, and entirely alien to the world of government and law.” And, as he writes of Linda Tripp, “By the time she injected herself into the story of the Clinton presidency, she, like so many people in this saga, had already had a difficult and unhappy life, and she had learned that she could rely on no one except herself.” In this context there’s something truly heartbreaking about the setting that, likely, can be considered as the origin point of the case – the salad bar at the Golden Corral steakhouse in North Little Rock where Jones ran into Trooper Danny Ferguson and Ferguson surmised that she might be able to make as much as $500,000 by selling her story to The National Enquirer. “Five hundred thousand dollars would last a long time,” Jones mused. And heartbreaking about the eventual fate of the Jones family – Steve Jones working the counter for Northwest Airlines at LAX, trying simultaneously to break into movies and to bring down the president. And heartbreaking even about the aspirations of the unlikely literary duo, Linda Tripp and her makeshift agent Lucianne Goldberg, who were willing to bring down the president and to betray Tripp’s erstwhile friend Lewinsky for the sake of a book, which, as it happened, was never written. “My tabloid heart beats loud” was Goldberg’s overriding thought when she first heard Tripp’s tale. And heartbreaking, most of all, to come across the real point of origin of the case, Paula Jones’ assignment to work the registration desk at the Governor’s Quality Management Conference on May 8, 1991. As Toobin writes, following on testimony from Jones’ boss Clydine Pennington, “Pennington remembered her bubbling excitement as she reported for work that morning….It was far from an ordinary assignment for Paula…She was going to dress up, get out of the office, and have the chance to meet high-powered executives, including, perhaps, the governor.”

What’s most touching in some sense about this whole constellation of characters is that Bill Clinton, in crucial aspects, wasn’t really so different from any of them. He grew up poor in Arkansas in circumstances not so wildly dissimilar to that of Paula or Steve Jones. Toobin makes that parallel explicit. The event at which he met Jones took place two days after a “triumphant speech in Cleveland” which signaled that “he was finally going to be a realistic candidate for president.” In other words, everybody at every point in the story senses a break – Paula Jones was excited to meet Clinton, as was Lewinsky; Linda Tripp, Lucianne Goldberg, all the lawyers, everybody was excited to get their piece of the pie; and in the end it was only Bill Clinton who got any sort of power and the lawyers who got their cut. The rags-to-riches aspect of the democratic vision has its dark side exposed in a story like Clinton-Lewinsky – the excruciating tale of all the people who were used-and-disposed along the way by a figure like Bill Clinton, the flings, the troopers, the bureaucrats, the various functionaries. Seen in that way, the Clinton scandal is their collective revenge – and the ‘vast conspiracy’ of Toobin’s title refers, really, to an assortment of regular people who crossed paths with Clinton at one point or another and came to feel that they were owed more than they had gotten. It becomes noteworthy that Clinton’s most determined enemies often are people, like Cliff Jackson and Hick Ewing, who have an eerie amount in common with him and who seemed to have felt that everything that went Clinton’s way was the direct result of Clinton’s ability to compromise his moral fibre – through glad-handing, through lying, through opportunism. Clinton’s appeal was, precisely, that he was the people’s president. With him there was no managed democracy as there often seemed to be with, say, the Bushes and Kennedys. He really had come from nothing and had made his way through that peculiarly American combination of intelligence and smarm. And his presidency, more so than that of virtually anybody who preceded him, was a mirror of the American people as a whole. And that is, of course, not a wholly unalloyed good. What it meant, in the most direct way, was that all sorts of unlikely, ‘unpresidential’ people became intertwined with the Clinton administration - Gennifer Flowers, Paula and Steve Jones, the whole Arkansas crew, Monica Lewinsky herself. And, after all the assorted dramas, the fun ‘mini-scandals’ tagging along with the Clinton years, it’s fitting that his presidency should culminate, really, not with the story of oral sex in the White House - a power move if there ever was one - but with the surprisingly tender phone calls between Clinton and Lewinsky, the president of the United States chatting about this and that with a 24-year-old now working some other job (and with the entirety of Washington’s legal apparatus attempting to parse those conversations for evidence of obstruction of justice).

The sheer strangeness of this sort of spectacle - popular democracy as it really is - accounts for the cognitive dissonance of the impeachment and trial, Henry Hyde waxing on for no apparent reason about various battles in American history, the Senators writhing around in their seats looking as if they would rather be anywhere but where they were, the Starr Report with its uniquely stilted way of writing pornography. The attempt was being made to put the genie back in the bottle, to restore some notion of decorum - but, by then, it was far too late and each attempt to get out of it only made the noose tighter.

Gephardt, the Democratic Minority Leader, put this more eloquently than anyone else. In an impromptu speech on the House Floor - he was responding to the sudden resignation of Bob Livingston for sexual impropriety - he said, “I believe Livingston’s decision to retire is a terrible capitulation to the negative forces that are consuming our political system and our country. We are now rapidly descending into a politics where life imitates farce, fratricide dominates our public debate and America is held tactics to politics of smear and fear.”

Which was a very valid concern - and Gephardt’s speech a sort of last stand of the moderated republicanism that the Founding Fathers had had in mind. But the soul of democracy is something different, the mix of high and low, the overpowering importance of public opinion, and, with the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal, the congressional patricians were looking at a particularly unattractive incarnation of that spirit.

The phrase ‘lowest common denominator’ is apposite. That’s what Bill Clinton seemed to represent to his opponents - politics-by-slime. Of course it turned out that were many lower roads to take than anything traveled by Clinton - it doesn’t seem to have occurred to Clinton, for instance, to have sent a mob to the Capitol during the impeachment proceedings - but he does share some amount of the blame for the degradation of political life that has occurred during my lifetime. Trump in his reptilian way intuited this - and he made a sort of false equivalency to Bill a centerpiece of his campaign against Hillary (the implication that any personal misconduct of his own wasn’t all that much worse than Bill’s and didn’t really matter anyway).

And Bill really was Trumpian in more ways than most Democrats would like to admit. The lying-to-his-own-lawyers episode admits of little other interpretation than that, by that point in his presidency, lying had become so second-nature to Clinton that he lost track of when he was doing it, that he inhabited a mental landscape comprised entirely of ‘spin’ (the forerunner to our ‘post-truth’ reality). He had a similar Teflon capacity for riding out scandals - and a conviction that his survival all by itself proved that the scandals really weren’t unethical. And, in so many of his personal dealings, he was bad news. Aspects of his treatment of Lewinsky make for really scuzzy reading – his declaration, for instance, “In my life no one has ever treated me as poorly as you have treated me,” delivered in the middle of a day in which he had been blindsiding her in her desperate attempts to see him and would, in a few hours, ridicule, to his own lawyers, the idea that he had had anything to do with her. As Toobin writes, “Self-pity and deceit are among the touchstones of his character.”

Those qualities of his would go on to have a lasting legacy long after his term in office – setting a new high bar for shamelessness in the White House and creating an election issue for Trump to use against Hillary. And, in that view, the classical theatrics by people like Gephardt and Dale Bumpers start to seem not so misplaced. There really was a golden opportunity for bipartisanship in the late 1990s - there were no real issues, there was no reason it shouldn’t have been an Era of Good Feelings. Instead, we got the worst hyper-partisanship in anybody’s memory. For that, the House Republicans, as well as a vigilante group like Ken Starr’s OIC, deserve almost all of the blame. But Clinton slipped and made himself a target for them - and the slip connected, as Toobin notes, to certain difficult aspects of his personality, his capacities for self-justification and hypocrisy. And, at the same time, a degree of national dignity vanished. “No other major political controversy in American history produced as few heroes as this one,” Toobin writes - everybody involved was in thrall to the legal process or their personal greed or some misguided attempt to spin their reputation, and the result of it was a completely self-inflicted humiliation that nobody had any capacity to stop.

I’m starting here to get into the sort of apocalyptic language of the House managers, so I should pause there just to say that the story is also just as funny and wild as everybody remembers it. Of all the comedic approaches to the scandal, there is something to be said for Toobin’s bone-dry wit. I laughed out loud at a discussion of how the release of the story of the ‘love-tie’ “led to much public merriment” or at a description of Lewinsky, her mother, and lawyer as “an excitable trio in the best of circumstances” to stand in for a scene in which they drive around in a car and scream at each other. And I literally couldn’t stop laughing at the interlude of the ‘perjury ladies,’ who, for no rhyme or reason, shuffled onto centerstage of the greatest political mass media events of American history, bewildered the nation for a day with their incoherent workplace tales, and then shuffled off again. And, in general, Toobin’s handling of every part of the story is commendable - a true ‘definitive history’ - which does, quietly and slowly, make the case that the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal was, all appearances to the contrary, a major event, a pivotal moment in the intersection of electoral politics and civil litigation and, very possibly, the moment when the political fabric started to irrevocably fray.

Paula was that case from beginning to end. Nice for her to get some love. Nice piece.

Ah ha ha!! The memories! Lucianne Goldberg. That's a name I haven't thought about in a while.