RASHID KHALIDI’s The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine (2020)

The last few weeks have been difficult for me with the Substack — and I often have the sense of living in denial. The situation in Israel/Gaza is an epoch-making event. However one positions oneself politically, there is no question that lots of people are dying; that lots of people will die; that the situation is beyond terrible; and that the future of the Middle East is to a great extent hanging in the balance. I don’t write about it very much, because both a) I find it very painful to think about; and b) I fundamentally don’t know that much about it.

The tendency I have — I guess, as an American — is to imagine that there’s some technocratic solution. That at some level everybody has to draw a deep breath, think less about the history, and deal with what’s at hand: the humanitarian catastrophe in Gaza; the negotiations on the return of the hostages; and the question of the role of the Palestinian Authority in Gaza. But more and more, I’m realizing that this is sort of the liberal American fantasy. Everybody in Israel/Palestine talks endlessly about the history. And people there have a greater sense of insuperability — that it is, in so many different ways, an asymmetric conflict; that, simply put, there may not be a solution. And to try to understand it better — I’m reading mainly Palestinian books at the moment —means engaging with genuinely thorny questions from the past.

A couple of different people have pointed me to Rashid Khalidi’s The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine as a good primer on Palestinian history, and that’s what I’m treating it as. There’s a lot in it that I just didn’t know, and if I found myself reflexively objecting to many of Khalidi’s conclusions, I’m also not in a position to argue them to the ground.

Khalidi, from a diplomatic Palestinian family and a professor at Columbia, frames his book as family history just as much as the story of Palestine, and that gives it a sort of cozy, intimate feel. Khalidi presents himself as the bookend to his great-great-great uncle Yusuf Diya, who in 1899 exchanged letters with Theodor Herzl and who, while somewhat personally sympathetic to Herzl, had a “prescient” sense of where the Zionist project was headed. Diya called it “pure folly” and concluded his letter by writing “In the name of God, let Palestine alone.” For Khalidi, everything in the next century-and-a-quarter is more or less contained in this exchange of cosmopolitan intellectuals — in Diya’s intuition of intractable conflict between two very different peoples inhabiting the same finite stretch of land; and, above all, in a contemporaneous diary entry of Herzl’s that alludes to “spiriting” the Arab population “discreetly” outside of its borders.

This idea of inevitable, unresolvable conflict, as embedded within Zionism, leads Khalidi to his thesis: that there simply can be no reconciliation; that the history of Israel/Palestine in the 20th century is understood as an unremitting war against the overmatched Palestinians. Here is how Khalidi puts it: “The modern history of Palestine can best be understood as a colonial war waged against the indigenous population, by a variety of parties, to force them to relinquish their homeland to another people against their will.”

There is much that is absurd, though, in Khalidi’s formulation, as he gradually admits over the course the book. His discription implies a unity of international actors and a unity of purpose — that the actions of the international community as a whole (!) are directed explicitly and malevolently against the Palestinians. Khalidi’s rogues’ gallery includes the Zionists, of course; the British (the fighting between Zionists and British in the 1940s is dismissed as a brief “falling-out between erstwhile allies”); the Americans; but also the Soviets, who by voting for UN General Assembly Resolution 101 in 1947, participated in a “declaration of war,” “sacrificing the Palestinians for a Jewish state to take their place”; and even actors in the Arab world, who, in the case of the 1982 Lebanon war, may have had an array of tactical objectives but treated the PLO as “a major target.”

Khalidi frequently finds himself backtracking on or qualifying his central claim to the point where it becomes unclear to what extent stands behind it. Very soon after framing the century’s-worth of conflict as “a colonial war waged against the indigenous population,” he concedes that it can be “understood as both a colonial and a national conflict” but then somewhat arbitrarily decides that his concern will be for its “colonial nature, as this aspect has been underappreciated.” By the book’s conclusion, Khalidi has very much blurred his own categories. “No one today would deny that fully developed national identities exist in settler states like the United States, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia, despite their origins in colonial wars of extermination,” he writes, and unexpectedly extends that spirit of historical amnesty to Israel. “While the fundamentally colonial nature of the Palestinian-Israeli encounter must be acknowledged, there are now two peoples in Palestine regardless of how they came into being, and the conflict between them cannot be resolved as long as the national existence of each is denied by the other,” Khalidi writes.

So it’s not really clear where that leaves us. The word ‘colonial’ is used to bludgeon Israel, but Khalidi acknowledges that there are legitimate national considerations to the Israeli state. Palestine is seen as being under assault from the international world, but that gets hard to defend when Syria, Egypt, and various Lebanese militias are lumped in as being among the oppressors.

What is inarguable, though, and what comes through clearly in Khalidi’s account, is the misfortune of the Palestinian people in the 20th and 21st centuries. He describes the Palestinians in the inter-war period as suffering from “a triple bind” — subject to colonial rule by the British, by the League of Nations’ Mandate for Palestine, and by what Khalidi calls a “singular colonial-settler movement.” This sense of a unique situation brings Khalidi somewhat astray from his anti-colonial talking points but (to my mind) is a closer match for discussing the particular plight of the Palestinians. The familiar arc of decolonization — whether from the Ottoman or British Empires — doesn’t fit the case of the Palestinians because they are dealing with a different set of people who are themselves, in large part, refugees and who have no “metropole” to simply return to. Khalidi’s presentation of the 20th century as a concerted international conspiracy to displace the Palestinians from their land strains credulity, but it is harder to challenge him on the argument that the Palestinians, without a state and for a long time without international voice, were subject to unique neglect: “Great powers have repeatedly tried to act in spite of the Palestinians, ignoring them, talking over their heads, or pretending they did not exist,” Khalidi writes.

The somewhat softer way to lay out Khalidi’s position is that he is contending, above all, with the phenomenon of Greater Israel — the thread that runs from the maverick Zionist Ze’ev Jabotinsky through David Ben-Gurion, Menachehm Begin, Ariel Sharon, and that may well be ascendent at the moment in Benjamin Netanyahu’s rightist government and that is interested in annexation and displacement. Some of the most harrowing passages in The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine are his description of being in Lebanon in 1982 and seeing the flares — “floating down in the darkness in complete silence, one after another, for what seemed an eternity” — that the IDF sent up to facilitate the massacres by Phalangist militias in the Sabra and Sbetila refugee camps. At times what Khalidi seems to be saying is that there is a valid Israeli centrist position, with a two-state solution and some sort of harmony, but that it keeps being undercut by the Israeli right.

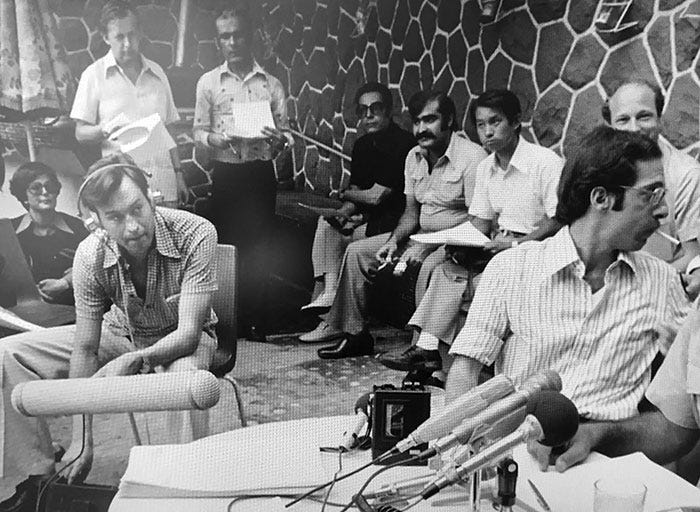

It is hard to read Khalidi’s description of Plan Dalet, in 1948, of the 1967 War, of Sharon’s operations in Lebanon in 1982 without being somewhat sympathetic to his position — that there is, at the very least, a strain within Israel that is sometimes ascendant that is dedicated to violently displacing Palestinians and to annexing as much land as possible. And I learned a lot from The Hundred Year War Against Palestine. In my sort of standard American Jewish education, the 1982 war was largely skipped over. The 1967 War was depicted as a fight between equals, if not an astonishing piece of luck for the Israelis. Khalidi sees it very differently, as a “long-planned preemptive strike,” with the outcome never in much doubt, and undertaken using the excuse (although I would question this characterization) of “empty threats by certain Arab leaders.” Khalidi also provides some valuable context on why the Oslo Accords proved to be so unpopular with the Palestinians — the sense was that the Palestinian side had simply been out-negotiated; and the timetable for a Palestinian state would be pushed indefinitely into the future.

But there is a great deal in Khalidi’s account that is clearly very slanted. It is difficult to accept his depiction of the result of the 1948 war as a foregone conclusion or his view of Israel as being almost immediately “a regional superpower” — that would, I think, have come as welcome news to the Israelis at the time who thought they were fighting for their lives as a just-born state at war with seven hostile regimes. It is striking that the 1973 war — which does not fit into Khalidi’s narrative of a super-powerful and hyper-aggresssive Israeli state — merits only a single passing reference. And Khalidi really pushes things when he chooses to describe the airplane hijackings of the “dynamic” PFLP in the 1970s as “external operations, seen as terrorist attacks by much of the rest of the world” or when he draws a puzzling distinction between the assassinations of PLO leaders by Arab states, which are forgiven for being “based on cold, calculating raison d’état,” as opposed to the on-the-surface very similar assassinations carried out by Israel, which are seen as “aimed at destroying the PLO or extinguishing the Palestinian cause.”

Where Khalidi is stronger is in presenting the Palestinians as having, in the 20th century, an impossible history — a people subject along several different matrices. There’s a colonial component (as he notes, the initial Zionist settlement took place during “the high age of colonialism” and the rhetoric of Zionism and colonialism sometimes bled together), a national component, a component of rivalries among Arab states, a component of, as Khalidi acknowledges, poor leadership among the Palestinians. Khalidi, with surprising transparency, gives, in his conclusion, several talking points for how to present the Palestinian case to the world: “the fertile comparison of the case of Palestine to other colonial-settler experiences”; a focus on the imbalance of power between Israel and the Palestinians; and a “foregrounding of the issue of inequality.” But I find it hard to pinpoint Palestinian suffering to any one of those things. It really is on many levels at once a very difficult, very grim history.

NATHAN THRALL’s A Day in the Life of Abed Salama (2023)

I’m not sure what I learned all that much politically from A Day in the Life of Abed Salama, but it is a bracing read — a virtually blow-by-blow description of a horrific school bus accident in Jerusalem and an unsettling portrait of life in the Occupied Territories.

First of all, let’s make clear what this book is not. It’s not an indictment of some heinous act of violence by Israeli forces. The incident in question really was an accident. A school bus, carrying Palestinian children on an excursion, was hit by a semi-trailer speeding the wrong way. The driver of the semi-trailer was Palestinian, and the immediate background to the accident is fairly mundane: an inexperienced driver inexplicably speeding on a rainy day. Thrall is at pains to exercise the structural inequality of the incident. The bus was old. The bus, due to checkpoints, followed a circuitous route. The Israeli ambulances and firefighters seemed conspicuously slow to reach the scene of the accident. “When Jews are in danger, Israel sends helicopters. But a burning bus full of Palestinian children, and they show up only after every kid has been taken away?” Thrall has one of his characters think to themselves.

But all of this is less than fully convincing. The accident, on the whole, seems like something that could have occurred just about anywhere in the world. The slowness of Israeli emergency services to respond is, in this circumstance, tragic but hardly by itself an indictment of the Israeli state. What is effective about A Day in the Life of Abed Salama is the depiction, through well-researched, indelible details, of life in contemporary Palestine. This is missing from much of the rhetoric around the conflict, and, by describing the love affairs, the home life, of a fairly typical Palestinian family, Thrall gives us a greater deal of empathy than is attainable from reams of political writing.

The early sections of A Day in the Life are the strongest. There’s the story of Abed and the intra-familial treachery that leads him into marrying first one woman and then another, both of whom are not the love of his life. There’s his experience under incarceration by Israel during the First Intifada, and it’s worth quoting Thrall’s description of his time in detention in 1989:

The tents had no tables or chairs and they flooded when it rained. The barrels used for trash overflowed each day, bringing a terrible stench and an influx of mosquitoes and rats. Many prisoners developed skin diseases. But the real torment came at sunset. Evvery night the Israelis would turn on the speakers and play a heartrending ballad by Umm Kulthum. The anguished prisoners would lie on their beds listening, homesick, some of them crying, others working on the one letter they were allowed to send each month.

What Abed takes away from the prison experience is the sense that all of Palestine just an extension of his time in prison. The color-coded IDs tightly regulate the movements of Palestinians. The Palestinian Authority is in the position of acting as guards. And Abed finds himself, against his better instincts, engaging in a complicated scheme to take a new wife for the sake of her blue ID card. “Abed thought it fitting; every Palestinian was a sort of prisoner, from the youngest child to the PA president, who also needed Israel’s permission to come and go,” Thrall writes.

What does come through is the sense of death by a thousand cuts. A Day in the Life isn’t a story of Israeli atrocities — although Abed is briefly tortured in his time in detention in 1989 — but of daily humiliation: Oslo, instead of generating an autonomous Palestinian political entity, “fractures the West Bank into 165 islands of limited self-government.” The color-coded ID system is demeaning; the delays at the checkpoints crazy-making. And Abed becomes exposed to the nightmare version of it, attempting to race between hospitals but stuck with the wrong papers, subject to bureaucratic obstacles just to see the scorched body of his son.

Abed is, in many ways, a less than fully sympathetic figure, but that doesn’t matter much. What stays with us from a book like this is not at all the personal morality, or even the politics, but just the sense of scratching the surface of a person’s life. There’s Abed’s tragedy of having married the wrong women — his inability to ever find peace after that. And then there’s the eerie story of another child on the bus who had been peculiarly fatalistic about the trip. “Why before? I’ll make it after?” his mother had asked when he was adamant about having zaatar flatbread before the outing. “‘No,’ he had insisted, ‘it has to be before.’”

Sam - thanks for this article. I haven't read either of these books. The first one looks interesting. My main takeaway from your article today is that no matter what we have been taught or what we might believe, it is important to read varying viewpoints with both an open mind and a critical analysis of the writer's bias and our own bias. I think the average person doesn't do those things. They just listen to whatever news source aligns with their general way of thinking or they consume media aligned with their way of thinking or they read books aligned with their way of thinking and so they reinforce their own bias. In most situations it isn't a simple answer of right and wrong. There are many complexities. And unfortunately while the majority of us are discussing the issues, real people are hurting, on both sides. Thanks again.