Ottessa Moshfegh’s Lapvona (2022)

Giving me real buyer’s remorse about Ottessa Moshfegh.

I thought My Year of Rest and Relaxation was absolutely brilliant, the best thing I’d read in a long time – and that it made Moshfegh my generation’s splenetic version of Henry Miller or Louis-Ferdinand Céline.

After that, she seemed to go into virtuoso mode, convinced (and with publishing industry enablers backing her in this conviction) that she could do anything. A murder mystery? Check. Historical fiction? Did it.

Unfortunately – as just about everybody who’s read it has realized – Lapvona is a very disgusting misfire, Moshfegh settling into a caricature of herself as the wicked witch of scatology and pulverizing her too-easy target (it’s not as if we really needed an exposé revealing the Middle Ages to have been brutal and unhygienic).

At the moment the bonfire of Ottessa Moshfegh is proceeding apace in the literary world – the critics that lauded her early, equally disgusting work but perceived some talent in it now turning on her, the whole thing very much like the sort of ritualized punishment that’s commonplace in Lapvona – and I don’t have too much to add to it. A really excoriating review in New York Magazine (“Moshfegh’s latest piece of shit is her new novel Lapvona”; “you will forgive her if her search [for transcendence] has led her up her own ass”) pretty much has my proxy. Lapvona is a truly terrible book – and it has me rifling through my memory of My Year of Rest and Relaxation wondering if I’d been had.

I have three stray directions of inquiry – which are 1) why Moshfegh would write something like this (i.e. why the regrettable choice of the Middle Ages); 2) what went so badly wrong; 3) how Lapvona got dragged into a wider-ranging conversation, particularly via New York Magazine, about ‘art for art’s sake’ and is starting to be used to discredit an entire school of aesthetic thought.

As for how this came about, the honest best guess is that Moshfegh – like everybody else – spent too much time watching Game of Thrones. Lapvona reads like fan fiction focused on the court of Ramsay Bolton. What GOT represents for us – the real reason, I submit, why it was so popular – is the widespread assumption that unadulterated brutality, the absoluteness of power, is in fact the underlying reality of the modern world. Civility, reasonableness, compassion – the directions of Ned Stark, Tyrion Lannister, the Prince of Dorne, etc – are again and again demolished, the realm of politics revealed to be a zero-sum struggle for power in which the born sociopaths have an inherent and enduring advantage. As the leading literary novelist of the ‘brutalist’ school of aesthetics – an approach that includes Tarantino, Lars Von Trier, Mike Bartlett, etc – Moshfegh is almost compelled to take in the Middle Ages, in which ‘brutalism’ appears in its purest state. Everybody else who’s reviewed the book has noticed the lack of commitment Moshfegh has to fully inhabiting her fictional world – the feeling is of children raiding the costume shop, Hari Kunzru in The New York Times calls her setting “medieval in the way that one of those village-building computer games is medieval,” and the utter lack of plausibility extends into language, with Moshfegh’s idiom slipping around as if her prose is always just on the brink of breaking character (the Steinbeckian, timeless “the ground had been so hardened by drought that the water just collected and stood and rose” pairs very oddly with the next line, the slackerish “the men of the village waded around, trying to remember the boundaries of their plots”) – but, of course, Moshfegh is aware of that and that’s part of the point. In Lapvona, the Middle Ages aren’t really a vehicle for historical fiction. They’re the nightmare which is set against our own enlightened progressivism – feminism, the dignified aloofness of Ina or Luka, Marek in his Ferdinand the Bull path towards the world of finer feeling – and through which we discover that we are limited always by our own nature, by our frail and repulsive bodies, by the pleasure we take in administering pain, and by the dexterous hypocrisy that we’re capable of deploying even when we’re avowedly and somewhat genuinely spiritual.

Moshfegh’s engagement with religion – though buried underneath the obligatory cannibalism and eye-gouging and servant-tormenting – is the most interesting aspect of Lapvona and goes some way (although not very far) to making it bearable to read. Andrea Long Chu’s review in New York Magazine really attempts to tweak Moshfegh on this point: Moshfegh, at a moment in her career when she could get away with saying anything she wanted to, had claimed that God was “the intelligence of the universe” and that in her own writing she had more or less a direct line to God,. To which Chu’s response is, “That’s a nice thought. It must be convenient to believe in a God whose theological features consist in giving you divine permission to write whatever you want to write.” But it’s exactly here, actually, that Moshfegh is on firmest ground. What she’s channeling – and what apparently draws her to the Middle Ages – is something like the pure Cathar vision, that the world is hopelessly irredeemable; that “the gates of heaven are still shut,” as the village priest blithely reports at some point; that anybody who aspires to a position of power or declares some sort of optimism signals, ipso facto, that they of the devil’s party; and that although life may be a cesspool of violence and dirty desire there is a certain wry camaraderie from all being in it together. At some point in the novel – Moshfegh really is a very talented writer and even in a book as misguided as Lapvona she can’t help herself from writing well sometimes – she comes up with the innovative theological insight that there is one set of morality for the rich and another for everybody else and that the two are curiously symbiotic. “If you didn’t have money you had to be good,” she notes – and, of the servants, “the worse [Villiam] behaved the more God loved them.” What this represents – in the spirit of ‘brutalism’ - is a theology that applies equally well to our hierarchical times: we seem to have given up on the Fukuyamaish vision that all boats rise together, that everybody defaults ultimately to an ambitious-and-yet-philanthropically-minded upper middle class, and we have reverted instead to a zero-sum mentality in which the rich are very rich and very selfish (with lackadaisical, bemused Villiam being no worse than any other feudal lord) and in which we take the scraps of harmony where we can find them, in the license to spit in the lord’s soup, in the mutually self-serving conceit that the narcissistic brutality that is needed to retain political order yields a coefficient of smug moral satisfaction somewhere on the other side of the tracks.

All of that being said, Lapvona remains utterly unreadable and would be a career-ender except that Moshfegh has enough accumulated capital from My Year of Rest and Relaxation and, for some reason, from Eileen, that everybody will likely have to put up with her for a long time to come. This is not the first time this has happened in my generation – each of the ‘once-in-a-generation’ writers, Jonathan Safran Foer, Lena Dunham, Joshua Ferris, Zadie Smith, Emma Cline, and now Moshfegh have washed out in short order, to the point where I’ve started wondering if there’s some pattern in what’s going on. The simplest explanation is that it’s really hard to write a great novel, that Moshfegh is absolutely right that it is essentially a channel to the divine, and that, when the inspiration fails, the once-talented-writer is left suddenly exposed, as Ferris and Smith were for an excruciating string of novels and as Moshfegh now seems to be. But I can’t help but feel that taste and the publishing industry have something to do with it. Writers are celebrated as their cartoon versions – Ferris as office desk anomie, Moshfegh for her unladylike toilette – and unless they are incredibly strong-minded, incredibly attuned to their inner voices (the amiable spirit of Benny Shassburger, the matter-of-fact vitriol of the Rest and Relaxation heroine), they very quickly become the worst possible versions of themselves. Ferris became unrecognizably bad; Moshfegh seems to be headed in that direction. And, unfortunately, the cartoon versions are very close to the ‘brand’ that everybody in their orbit counts on: Moshfegh is a writer of darkness, so of course she has to do a murder mystery and a morbid medieval romp. For her to move forward, she would have to clear out the clutter, really tap into her inner voices, start fresh.

The disastrousness of Lapvona has created a target not only of Moshfegh but of a smattering of aesthetic principles that she was reckless enough to agitate for. She had announced last summer that “a novel is not BuzzFeed or NPR or Instagram or even Hollywood. A novel is a literary work of art meant to expand consciousness. We need novels that live in an amoral universe, past the political agendas described on social media.” But – since the promised amoral universe turns out to be very sketchily-drawn scenes of adults sucking on witches’ breasts and servants eating poop-smeared grapes – a critic like Long Chu feels empowered to turn the claim upside-down, to insist that, in fact, all art is political and probably, come to think of it, should have a moral agenda. And so – to nobody’s surprise – we end up in one of these useless, Twitter-ready artistic tugs-of-wars, to which Moshfegh has unfortunately made herself complicit. We really should be able to do better than, on the one hand, art for art’s sake and, on the other, engaged activism. What makes art work is a voice, a vision, and – as Moshfegh guilelessly pointed out – inspiration. The brazen bad taste at the end of My Year of Rest and Relaxation worked, not because it was transgressive but because Moshfegh had fully committed to her heroine’s inner voice and had the nerve to stick with it even though the novel’s last sentence would alienate half of Goodreads. Lapvona started from a place of tweaking rather than inspiration – simple as that – and no amount of bad sex or brutal death could make up for the lack of an underlying, sincerely-felt vision.

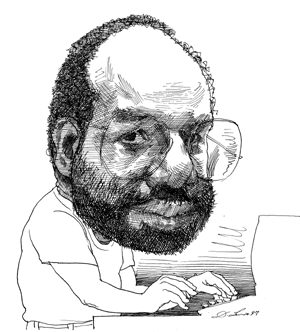

Patrick Chamoiseau’s Slave Old Man (1997/2018)

In the middle of my desultory reading this week – Ottessa Moshfegh’s Lapvona, Tommy Orange’s There There, Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous – it was useful to remember that such a thing as a great novel can exist and that it may be comprised of deceptively simple elements: intensity and a great freedom and confidence of expression.

Slave Old Man, published in French in 1997 and translated into English only in 2018, is my introduction to Chamoiseau and to Martinique’s literature and there’s the sensation of wiping dust from my eyes that it seems everybody experiences when for the first time they come across the writers’ paradise of Martinique. The famous story – which, admittedly, I hadn’t heard before – is that André Breton, fleeing Europe in 1941, was forced to spend three weeks interned in Martinique and, picking up a ribbon for his wife at the haberdashery, came across Aimé Césaire’s journal Tropiques and immediately concluded that Tropiques represented the future of literature, which at that moment was all-but-extinct in Europe. “I couldn’t believe my eyes. What was being said here was what had to be said, not only as well as it could be said but as loudly as it could be said,” Breton wrote. In Tropiques, there was – much to Breton’s satisfaction – a premium placed on surrealism as a mode for revolution and dissent, an undercutting of the very premise of rational reality not to mention the societal power structure and, in their place, a boundless inner freedom. Not only did there seem to be a blending of the ‘real’ and the fantastical, but there was a sense of mélange in virtually every conceivable way – of culture, of language, of the oral and written traditions, of the past and present. Milan Kundera, discovering Martinique’s literature through Césaire’s heir Édouard Glissant and through Glissant’s heir Chamoiseau, wrote, “There are liberties with French that no French writer could imagine taking.” Derek Walcott, who grew up in St. Lucia within sight of Martinique “and its pale blue silhouette sometimes so clearly edged that one can see the outlines of houses” wrote disbelievingly of Chamoiseau’s Texaco, “A great book has been written, a book whose elation cracked my heart.”

The sense, for these usually-not-so-easily-impressed writers, is that Chamoiseau and the tradition he is working within have managed to dig underneath the calcified form of the bourgeois novel (what Kundera calls the 19th century novel) and to return to a more charged exchange between writer and reader in which the writer is closer to the figure of the storyteller, capable of actively shifting perspectives, of fabricating, of performing in a way that it is virtually irrecoverable in a strictly written tradition where the writer is assumed to be a more or less dry chronicler of events that have occurred off in some fictitious realm. And, with Chamoiseau, there is something not-quite-to-be-believed, the taut fiber of legend but in written form, the rhythm of a storyteller in full flow, a moment of incomparable richness which Kundera describes as “oral literature is in its last hours and written literature being born,” and with the resources of both modalities are readily at hand.

The strength and confidence of Chamoiseau’s art are obvious right away in Slave Old Man – the introductory description of the hero as “a lover of silence, a taster of solitude,” the sense in the tour of the plantation that the hero, who is distinguished in no clear-cut way, is nonetheless, at his core, a figure of legend, “has no opinion on the fertility of the different fields, announces neither weather forecasts nor harvest estimates from a simple sight of the first sprouts….departs not a whit from correct servile behavior,” but is subtly marked, to the deep unease of both master and fellow slaves, by a certain ‘non-acceptance,’ a subtle but adamant independence that reaches to the deepest part of himself. And the narrative through line follows, in linear, epic fashion, from the underlying dynamics of the old man’s core self – he must be free, which for him is a compulsion, a form of madness, and the master and the master’s hideous mastiff are equally hellbent on catching him and their inner compulsion is no less intense and passionately felt than the old man’s (in fact, as the old man ruefully thinks at a low moment in his escape, the dog’s “will for killing is a good deal stiffer than my longing to live”).

As in all good legends, the end of the story is foreordained from the beginning – and there is a certain narrative strength that follows, interestingly enough, from the topography of Martinique. In contrast to runaway slave narratives from the United States, there is no possibility of the Ohio River or the Canadian border – Martinique is an island and a slave island and masters and slaves are locked, till the death, in the unequal struggle between dominance and freedom. The old man’s escape – for which he has stored up the entirety of his life’s energy – has nothing to do with any hope for physical survival. Encountering the mastiff – the embodiment of the slave system – he simply must challenge it, must strike out suicidally into the forest and must make it as far as he possibly can with his inevitable death a statement of will.

The narrative structure, with its sense of the ineluctable recalling Moby Dick, The Stranger, the Greek myths, would seem to generate a stony, acerbic texture, and here is where Slave Old Man is most interesting – in its loose, sensuous prose, in the sliding of perspective from third to first person, in the gliding-around of consciousness, from the old man to the master to (most daringly) the mastiff, in the sense of physical reality itself dissolving somewhere in the midst of the escape very much in the style of Ariel’s ‘nothing of him doth remain’ song, and with thoughts “warping,” as the old man observes of himself, and the characters molting into pure spirit.

These are the really bravura passages of Slave Old Man – the traversing of the characters’ consciousnesses out at the extremity of their physical being: “He quickens his pace, provoking an onslaught of hallucinations. Broken shells, religious shames, how many women’s emotions, enormous milky breasts, murky not-very-manly desires, how many delicious sins and infectious innocences. How many intimate collapses, including even the worst heartbreak-coeurs-cassés. All this frightens him, without being unfamiliar.” Somewhere around here, I put on William Basinski’s ‘Disintegration Loops,’ which I really recommend as music to accompany Slave Old Man – a sense of the power of repetition and of a very simple, insistent forward momentum to create, with time, the impression of a cosmic change-of-state.

There are other elements of exhilarating writing in Slave Old Man – and not all of them, unfortunately, are readily discernible to readers dealing with a translation. For native French speakers, the great thrill of Chamoiseau’s writing is the mixture of French and Creole, the shifting of registers, the way in which Creole functions like an exclamation mark in the prose both heightening and deepening it. (“The rest of it cannot be described in this tongue,” the narrator declares at one point, pausing for breath and turning towards Creole. “Let ancient sounds and languages be brought to me.”) Equally thrilling is the appearance of first-person narration, which, with very little inner restraint, is able, midway through the novel, to take over the old man’s perspective without losing the ability to tack back and apostrophize the audience: “I will, without fear of lies and truths, tell you everything I know,” announces the narrator at one stage, which is the kind of ringing line that deserves to be emblazoned over writers’ desks - being unafraid of lies is one thing but it takes extraordinary courage to be unafraid of truth!

But what Chamoiseau seems to be after more than anything is some sort of dissolution of the whole master-slave dialectic. This would be a remarkable achievement for a very slim novel, but, curiously, Chamoiseau actually kind of pulls it off. This is the ‘magic’ that Walcott finds in Chamoiseau and which is embodied within the narrative of Slave Old Man most in the figure of the master, the existential confusion he encounters in finding himself drawn deeper into the woods than he would have believed possible, coming across a sense of vertigo at some point in his hunt – “crying over the triumphant failure that had been his life.” The point is that somewhere in the depths of the woods – and this, actually, is very Shakespearean – the power dynamics disintegrate, the old man passes out of sly rebellion and the master out of anxious defensiveness. And at that moment – and this really is an extraordinary effect – Chamoiseau’s writing, at an acme of delirious eloquence, collapses into silence. “He returned bearing something he could not name – in him, now, other spaces were bestirring themselves,” he writes of the master. And, of the old man, writes, “A warrior unconcerned with conquest or domination, on the run towards another life, of the world’s humanization in its wholeness.”

At this moment in my life, the art I’m coming across (c.f. Lapvona, etc, etc) seems to take for granted the permanence of power dynamics, the immutable revolving-door-ness of the master-slave dialectic, and so it feels like a gift from some other dispensation to encounter Slave Old Man with its confident insistence that art and consciousness transcend, that there is some domain, outside of reality and outside of power, in which slave, master, mastiff speak fluently to one another.

Sweet!

Taking "Lapvona" off my Amazon shopping cart.

Thank you @Juliet Shrier for putting me onto this Substack! So much time to take in here....