Dear Friends,

There are a large number of new people this week. Welcome! Thrilled to have you here! As introduction, this Substack tends to be a bit heterogenous in style and subject matter - and moves, throughout the week, between politics, aesthetics, fiction, book reviews, and impressionistic personal writing. The weekly essay is below.

Best,

Sam

MY VAPID GENERATION

I was a college freshman in 2004, the year Facebook came out. Mostly, of course, it seemed like a fun new toy – I’d spent an embarrassingly long time preparing my bio for the student directory, assured by my parents that people pored over that, and it seemed kind of cute for that to be less engraved, updated in real time – but it was noticeable, very quickly, that there were people who you started to never see out, who spent all their time on it. A group of wiseguys were very amused by the ‘groups’ feature. They started creating groups for everything, groups for – ‘Kyle, would you please get out of the shower and meet us in the dining hall,’ groups for ‘Movie when we get back from the dining hall?’ – until administrators from The Facebook, allegedly Zuckerberg himself, actually got ahold of them and told them to knock it off.

Looking back, I feel like those guys had the right idea – and the rest of walked into a really terrible trap.

At the time I was thinking a lot about my generation – what my generation would represent – and I was sort of drawing a blank. It seemed that whoever we were would have a lot to do with the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan – maybe we would protest, maybe we would be a new ’60s generation. But even in 2004, that seemed unlikely – the radical kids would say mean things about Bush, protest something or other having to do with Israel and Palestine. The general idea was that we had inherited a very good world – the aberration of 9/11 and Dubya notwithstanding – and we would make it better, more equitable, more just, more creative. Obama’s election seemed like a fulfillment of every piece of that.

What we really were, of course, was the beta-test for a new set of technologies – for all of which we proved to be excellent and malleable test subjects.

If it hasn’t already been recommended to you, it’s really worth reading Martin Gurri’s The Revolt of the Public, which is by far and away the best book I’ve read about our demented time. Published quietly in 2014, The Revolt of the Public was dug up after 2016 as the ready-at-hand analysis for the twin shocks of Trump and of Brexit, but, actually, Gurri’s main argument ran deeper than that and had to do with a reshaping of public space and the flow of information. In his view, we had spent about a century-and-a-half in a ‘mass’ mindset, in which a figure at the center of authority radiated out information and everybody absorbed it – radio, television, and really just about any institution encoding this same flow of information. But the internet created a completely new modality for information, and by 2011 – the central year in Gurri’s cosmology – it had completely transformed the world. This wasn’t so much what everybody had kind of been anticipating – an alternate reality, a kind of nerdverse (the game ‘Second Life’ seemed indicative of the trend) – but a shadow realm that interwove with regular life, had more power than ‘real life,’ and cast judgments upon it that were simultaneously instant and permanent.

This is all a familiar story by now – the collective nightmare we’re all sharing. What I want to do is just give a few notes on what it looked like for the millennials in the 2000s – a more innocent time – which turns out to have been ground zero of our dystopia, our universalized addiction. At the time the internet seemed like an invading army and there was a certain pride in repelling it from campus. I was so impressed with my best friend, who stayed up all night for several nights, spamming a particularly noxious forum, JuicyCampus, which printed anonymous gossip – almost entirely about sexually-active women. My friend copy-and-pasted feminist manifestoes onto the forum so that anyone trying to read gossip had to scroll past hundreds of pages of The Second Sex until the JuicyCampus administrators pretty much gave up. But that was like John Henry racing the drilling machine.

Was there any way that the internet could have been beaten off? Of course not. As is shrewdly analyzed in the documentary The Social Dilemma – the must-watch film about our current reality, just as The Revolt of the Public is the book – digital technology basically implants itself deep enough in the brainstem that there’s no way of evading it. “Delete. Get off of the stupid stuff,” says Jaron Lanier at the end of The Social Dilemma. Oh yeah? Try getting through a white-collar workday without this technology. But the appeal is of course even deeper than that – the dopamine hits of incoming messages, and, most important, the conception of status made tangible and accessible. As a college freshman, it suddenly seemed very important to walk around campus and make enough facebook friends so that your number was respectable – it was like some kind of deep secret, like the number of sexual partners you’d had or something, suddenly becoming the first thing everybody knew about you. Within a few years of that, Wikipedia became the real arbiter of status – if you had a Wikipedia page, then you’d really made it. And then of course the ‘like’ button became the most concise form of virtual currency.

So it’s hard to be too critical of my own generation. We were, I suppose, the first victims of what was coming. But here’s the thing – and here’s what I’ve been grappling with for the last decade – we were somehow the perfect suckers for it. We were 1) guilelessly trusting in technology; 2) guilelessly optimistic about ‘progress’; 3) believers, implicitly, in the market as a determinant of worth. So when confronted with a new mode of communication that was 1) technologically advanced 2) represented the new and represented youth 3) had a kind of currency built into it that actually, in certain remarkable circumstances, could be swapped for cash like when checking out of an amusement park, we were completely ensnared. And just about everything we created over the next decade or so tied in with those values. All of the cool new websites turned out, inexorably, to be click-bait and listicle-driven. Sites like Mic or The Huffington Post or Vox that started out with some idea of generating thoughtful independent content found very quickly that virtual currency, and occasionally real currency, poured in from the narrow toeing of some particular ideological line. And the next turns of the wheel – demagogues running for president on Twitter; online mobs torching professional reputations, tech companies-turned-cultural-powerhouses censoring as ‘misinformation’ any ideas they deemed inappropriate – all, in a sense, easy enough to predict: the culture made bite-size, palatable, replicable, ADHD’d, the word ‘viral’ the perfect metaphor for our lousy era.

I don’t think there was any way to stop any of it, any more than the Luddites smashing knitting machines were ever going to end up on the winning side of history – although it’s hard not to admit that they had a point. There were people who saw what was coming – and not just my professors intoning from their lecterns to stay off Wikipedia and look up everything in an encyclopedia. Deleuze was right when he compared the modern information nexus to a serpent and claimed that “the coils of a serpent are even more complex than the burrows of a molehill.” Everybody muttering about neoliberalism was right – but, at the time, that was only the theoretician grad students, who nobody could understand anyway. In retrospect, the best thing that happened for me in college was that I never figured out how to use wifi – I relied on Ethernet cables – and I actually kind of did pay attention in class while everybody around me was surfing, and I procrastinated on papers by playing alone at one of the dorm pool tables – nobody else was ever there – and since that was only somewhat absorbing I’d return after a while to write my paper, and who knows what would have happened if I’d had the whole internet to procrastinate with. But that was only a temporary stopgap, of course. A year or two later I bought my first iPhone and the resident genius said, “Welcome to Apple” in such a nonchalantly smug way that I really was creeped out. But then, inevitably, I was hooked.

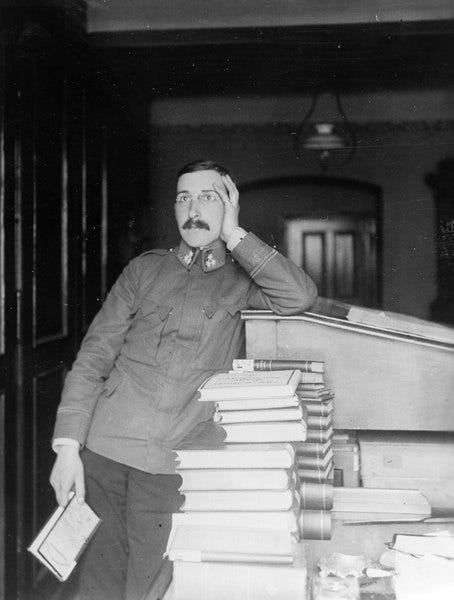

So blame isn’t the right word – no matter how annoying the Zuckerbergs, the tech bros, the amoral programmers, the whole metastasized revenge of the nerds. Regret is. I suppose I started to pick up on how deeply depressed I was about the whole thing when – in the odd moments between cell phone notifications – I read obsessively about the 1900s and 1910s, and this wasn’t some sort of costume drama escapism, it was the feeling of watching a whole generation sail together off a cliff. It’s not a perfect comparison between the Guns of August and XCheck, but I was in an apocalyptic mood – and, apart from the neat symmetry of dates, there was the boundless gullibility of our two generations, thrilled to be part of an era of technological dynamism, curious – above all else – to see where it led.

Again and again, in the books I read – Gabriel Chevallier, Jaroslav Hasek, Leonard Woolf, D.H. Lawrence, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Stefan Zweig – I got to the critical moment, the rupture: a Britisher spending a very enjoyable summer with friends in Germany, suddenly, on his return, stopped and his papers checked; the concert in the park in Vienna, the music suddenly stopping, the haphazard news that the unpopular archduke had been shot. And everybody with the same sense of bafflement – how could this completely different nightmare reality, trench warfare, poison gas, civilian bombing, intrude on their summer idyll? But, to the more perceptive observers, it made a certain kind of sense – it was like the whole civilization had been asking for it. There was the reckless adventurism that had spurred a series of random Balkan wars in the preceding few years, there was the intemperate romance of war (Marinetti’s “hygiene of the people”), there was the “brittle masculinity” as described by the historian Christopher Clark that inspired emissaries to weep on one another’s shoulder as they delivered their mutual declarations of war, there was the ingrained veneration of institution and authority, there was the deep dark secret of colonial brutality, which, as a byproduct, beta-tested exactly the killing machines that proved so effective on the Western Front. And then – as if to disabuse any pretense of collective innocence – there was the widespread enthusiasm for war, even if on the slenderest of pretexts. “To be truthful I must acknowledge that there was a majestic, rapturous, and even seductive something in the first enthusiasm of the people,” wrote Zweig decades later. “And in spite of all my hatred and aversion for war, I should not have liked to have missed the memory of those first few days.”

So. Look. I’m a few drinks in at this point. I’m not all that interested in threading back to the original departure point for this metaphor. I don’t know how cataclysmic the whole digital era is – but it should be obvious by now that it’s leading nowhere good, and all of the initial selling-points, democratization of information, formation of community, disruption of capital, have all been thoroughly discredited as corporate propaganda. The point is that we, the first generation to go through this, brought this upon ourselves. We were vapid at the time – and we knew we were vapid and were proud of it. We were completely uninterested in history; the Iraq and Afghanistan wars were something happening to other people; the terms ‘globalization’ and ‘neoliberalism’ were the province of annoying graduate students and washed-up labor leaders; we were on the side, of course, of whatever was new and cutting-edge and we wanted to ride the wave. Well, fuck us. We got what we deserved.

Did you ever read E.M. Forster's "The Machine Stops"? It describes an astonishingly familiar world of life in front of a screen, though written in 1909! I wonder what Forster experienced at that time that would have inspired his vision. Perhaps it was just the disembodied communication enabled by the telephone that presaged lonely lives in the future?

I get that what I'm about to say may be way under the radar for you, Sam. But here goes: D.H. Lawrence, who somewhere along the line went out of fashion, was in his own way a prognosticator of what I perceive to be your argument. I'm excluding _Lady Chatterley's Lover_ in this comment and focusing more on _The Rainbow_ and _Women in Love_ --and his attack on industrialized society, let alone everything else he was notable for discussing before fashionable. Anyway, open to your super savvy reaction to this, probably strange, comment for most of your readers. But who knows? Maybe you do ... . xo Mary