My Insane, Degenerate, Overpowering Chess Obsession

And: A Century of Chess The Book!

Dear Friends,

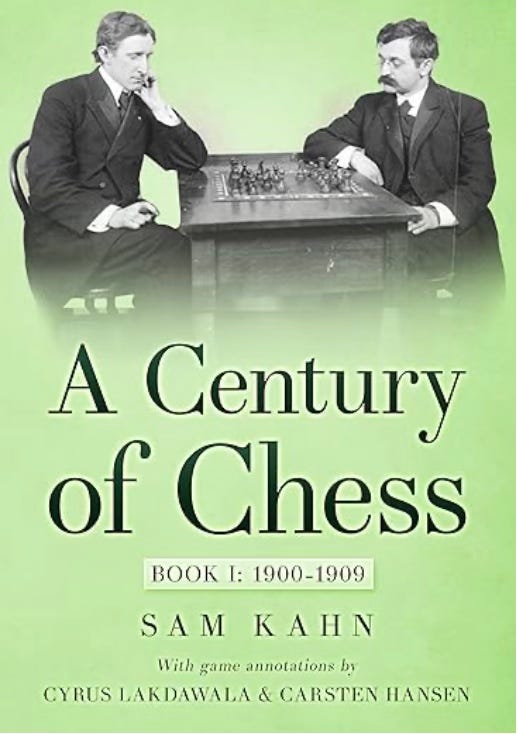

I’m very happy to share that my book A Century of Chess: 1900-1909 is available for purchase on Amazon both as a paperback and on Kindle. The book is published by CarstenChess and has game annotations by IM Cyrus Lakdawala and FM Carsten Hansen.

I’ve already put up my description of the book here. It’s based on a blog I’ve been keeping in my other digital life on chess.com. The idea is to treat chess as an art that’s not so dissimilar to music or literature and to work through chess history paying particular attention to the evolution of ideas and to the stylistic contributions of the various masters. The book is, honestly, pretty technical for people who aren’t somewhat-serious chessplayers, but, if you happen to be a chessplayer, this is a pretty unique project — an unusually consolidated and in-depth tour of chess history.

Since I’ve already talked up the book on Substack, I’d like to use the rest of the post as a confession on my now-nearly-lifelong, totally-crazed, totally-overwhelming chess obsession. I’d break it down into a few different phases.

-Chess as royal game. I learned how to play chess when I was about five or six. We had kind of an active chess scene in the games-playing section of my kindergarten classroom — one kid there was touted by Chess Life as being the “next Bobby Fischer” but is now a fashion photographer — but I didn’t pay much more attention to it than I did to, say, Connect 4. I didn’t think about chess again, really, until I was 11. I had a weekend day, one of these long, slow Sunday afternoons, in which I somehow came up with the idea that I would master chess — and then, after I’d done that, maybe learn Go or Shogi or something. My dad happened to have a copy of Irving Chernev’s Logical Chess Move by Move, which featured mostly classical games, and, within a few pages of it, something irrevocable happened to me.

What chess seems to be fundamentally about, I think, is finding the limit between the finite and the infinite. It really doesn’t seem to be such a complicated game — 32 pieces on 64 squares — but the number of possibilities in it are, claim the mathematicians, greater than the number of atoms in the universe (whatever that means), and — this was already what I’d started to experience on the lazy Sunday afternoon — just as you think you approach mastery or understanding of the game, it turns out that the game has always a little more complexity in reserve. The very oldest quote we have on chess comes from 7th century India. It’s also the single best quote on chess and it holds that chess is: “a game where a gnat may swim and an elephant may drown.” That line sort of contains everything actually, but the way I started to feel it was specifically as an object lesson in humility.

I felt, through writers like Chernev, that I was getting mainlined into me something of the inner heart of the Western tradition. Chess was pure reason and pure logic. The stories of early chess history often had to with princes, pirates, renegade priests. The greatest players seemed to encapsulate something essential about their periods — the French Revolutionary masters who figured out a populist, pawn-based strategy to the game, then supplanted by the Romantics who were all about dashing attacks and sacrifices, followed by the rigorous German scientific approach which replicated Prussian military discipline, followed by the brute-force Soviet attempt to perfect the game — and for a history-mad kid, there seemed to be nothing better than a game that had every historical element in it. But if I thought that chess would be some sort of gentlemanly, aristocratic experience, what I ran into instead was a very different reality of chess in New York City. There were the grubby, scholastic tournaments, highly deficient in good sportsmanship but with a lot of kids of annoying levels of talent and tenacity; there were the two rival chess clubs with their mix of old-time New York hustlers and dead-broke Russian émigrés; and there was the street with its two, three, and five-minute games, its money odds, and its gamesmanship.

-Chess as degeneracy. Of those three, I vastly preferred the clubs and the street to the scholastic tournaments. I turned out really to not be very good and so had my humbling experiences everywhere, but the clubs and streets were an initiation of a different kind. As my dad put it at the time, “You’ve already met a lot of successful people. But there are a lot of people out there who are very intelligent and just don’t succeed.” And that’s who I started coming across. There was a whole vast underbelly of these people, who could kick my ass in a game of pure mental ability, but who were living like, really, on the margins. There was Asa, who had been to Columbia but dropped out to be a hustler, talked like a Damon Runyon character and wouldn’t do a thing unless there was some money to be made; there was Jay, who in a book described himself as ‘America’s most relentless player,’ estimating that he played 100 tournaments a year, and who would become my white whale as a competitor; there was Carlos, a Cuban refugee who had the most beautiful playing style I ever saw; Juan, who wandered around the club like a professor rebuking everyone for when they played contrary to chess logic and who is currently dying of ALS; Michael, who was the worst loser I ever met and would spend long minutes after every lost game proving that he had been winning the entire time and who died of cancer in his 30s.

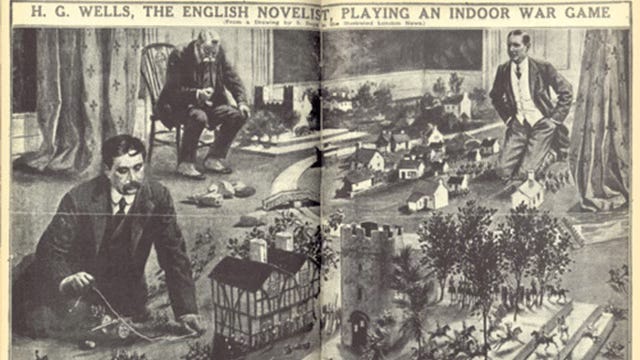

They were all smart, they were all master-level players, and they were all living totally hand-to-mouth, some of them not able to afford the entry fees to the tournaments. H.G. Wells in an essay in 1897 had described these sorts of unfortunates as “a class of men — shadowy, unhappy, unreal-looking men — who gather in coffee-houses, and play with a desire that dieth not, and a fire that is not quenched.” But, for me in my adolescence, this was all completely thrilling. I was being exposed to the adult world — and to a deep end of it — and, at least at the club, over the board, was taken in by it on equal terms. Chess is one of the very few activities that has no age limitations in it whatsoever. Little kids, adults, and old people would play each other routinely at the club — and would all play with equal ruthlessness. So long as I was serious about the game — and everybody could see that I was — I completely belonged there.

-Chess as metaphor for merit. In college there wasn’t as much opportunity to play, but once a week the chess club met in the back of a dining hall and there was a chance to play blitz for a few hours. There was absolutely no overlap between the artsy, creative crowd I normally hung out with and the members of the chess club, but every week I looked forward to the Saturday blitz games with real craving. By this point I had mostly given up on the idea that I would ever be a high-level player. I just didn’t have the right brain for chess — strong players tend to have good pattern recognition, good visual memory, and basically the same brain that makes good mathematicians (a touch of autism seems also never to hurt) — while my brain, which is all verbal, didn’t have that much to contribute. But I found myself becoming obsessed with the idea of what exactly made one person better at this activity than another.

Within the somewhat linear-thinking, acne-and-testosterone world of the college club, the answers to that were fairly obvious: it was pure intelligence combined with unremitting aggression. Julian Barnes has a chess essay in which he describes hearing two grandmasters incessantly use the phrase “TDF,” and assuming it was some arcane bit of chess strategy, until it was revealed to stand for “trap, dominate, fuck.”

But I just had the persistent feeling that there had to be more to merit than that. By senior year of college, when I was supposed to be looking for jobs, or writing a senior thesis, or talking to my girlfriend, I found myself almost smuggling chess history books out of the library. At the time, these seemed cozy and a bit embarrassing. Now, I understand better what I was trying to get out of them. At that time, frat boy jerkoffs were being offered six figure salaries to work at investment banks; my sainted college professors were complaining ferociously about the state of academia. More and more, what I’d understood to be ‘merit’ seemed like different kinds of rackets. But, at the highest levels of chess — much higher than anybody in the college club could play — there seemed to be something gentler, something approaching harmony and truth. “On the chess board lies and hypocrisy do not survive long,” the world champion Emanuel Lasker wrote once. The books I was checking out of the library were mostly game collections by great players. What they were doing was laying out their approach to the game — it was in line with the logical dictates of tough, competitive play but it also reflected, at an extraordinary deep level, their distinct personalities. In other words, chess was a kind of perfect distillation of art.

-Chess as addiction. I assumed that at some point, I would outgrow chess, that I would just get too busy with work or relationships, but that never happened. And at different, dark moments, chess did seem to be taking over my life. At night, the quaint Village Chess Shop turned into a gambling den for chess and poker and in my mid-20s there were at least a few weeks when I started spending long chunks of the night there. I have the searing memory of getting caught on the hook of a Filipino caterer, who wasn’t as good as I was but played exclusively at a two-minute time control where he could usually manage to win on time. We started playing in Washington Square Park before sunset, moved at some point after dark to the Chess Shop and at some point to a nearby McDonalds and only stopped in the morning when he said he had a catering gig and he frog-marched me to an ATM so I could pay him the $150 or so that I now owed him. Much more pernicious than that, though, was online chess, which was just becoming a thing. That took up whole nights, and became very difficult to fend off in the dead time at work, and was almost unavoidable whenever I sat down to try to write.

At some point, I really believed that chess was actually the main impediment in my life. I was curious to know how many plays or stories I might have written if I hadn’t gotten distracted playing blitz chess instead. I thought that maybe it had seized invaluable real estate in my brain and was preventing me from developing some more wide-ranging, age-appropriate pursuit. And I felt that I must be stunted through it. It seemed not great that I tended to put myself to sleep with chess lists — counting grandmasters as opposed to counting sheep — and that, if I saw certain words, like ‘Czech’ in a newspaper or ‘cheese’ on a storefront, I would see them as ‘check’ and ‘chess’ and get excited.

But, little by little, the addictive side of it wore down and seemed less overpowering. It started to seem like a not-particularly-malignant hobby. Some people smoked cigarettes to take a break during their work; I played a blitz game of chess — and the switch from writing to a purely visual/mathematical task seemed to quiet down my brain. I had believed ever since adolescence that chess was a completely non-transportable skill — i.e. that being good at chess gave you no benefits whatsoever in any other activity — but the more I wrote and the more I felt confident in writing, the more convinced I became that that wasn’t exactly right. There was something in the flow of a well-played chess game that was exactly the kind of structure that you wanted to get in a story — or, probably, in any other art form. There was a sort of ease, flexibility, and confidence in developing one’s pieces; there was a sense of a crisis point when you really had to stretch your nerves to the maximum; and then a carefully executed denouement. What you learned to avoid, above all, was shortcuts and tricks. In chess, you started to feel dirty and disappointed if you won through some blunder. On the other hand, a well-played game would, even without anybody trying for style points (both sides were just really trying very hard to win), end inevitably in a feeling of tremendous aesthetic satisfaction. Chess wasn’t some of kind of conspiracy against life, as Wells had written and as I’d often believed. The two paired nicely. “There are some people who enjoy thinking,” the world champion Mikhail Botvinnik wrote matter-of-factly, “and for them there is chess.”

-Chess as object lesson. As chess became more harmoniously integrated with my life, I thought I started to understand the really deep lesson of it — that chess is, above all, the art of losing. The addictive and destructive aspects of it come from pride and from the horrible ego-death of any loss. In chess there really is no luck, so any time you lose you can only blame yourself — and it’s not even like losing at arm-wrestling or in a footrace, you lose always and only on account of your brain, because you are stupider than your opponent, and, if you’re playing seriously, your opponent as often as not is a surly eight-year-old or a drooling welfare recipient. I can’t count the number of times I’ve gone careening down W.10th St outside the Marshall Chess Club or lurching out of a city park just beside myself at how defective my brain is. But then at some point — if all goes well — you learn to not be so bothered by that. Usually it takes many thousands of games and many thousands of losses to get there.

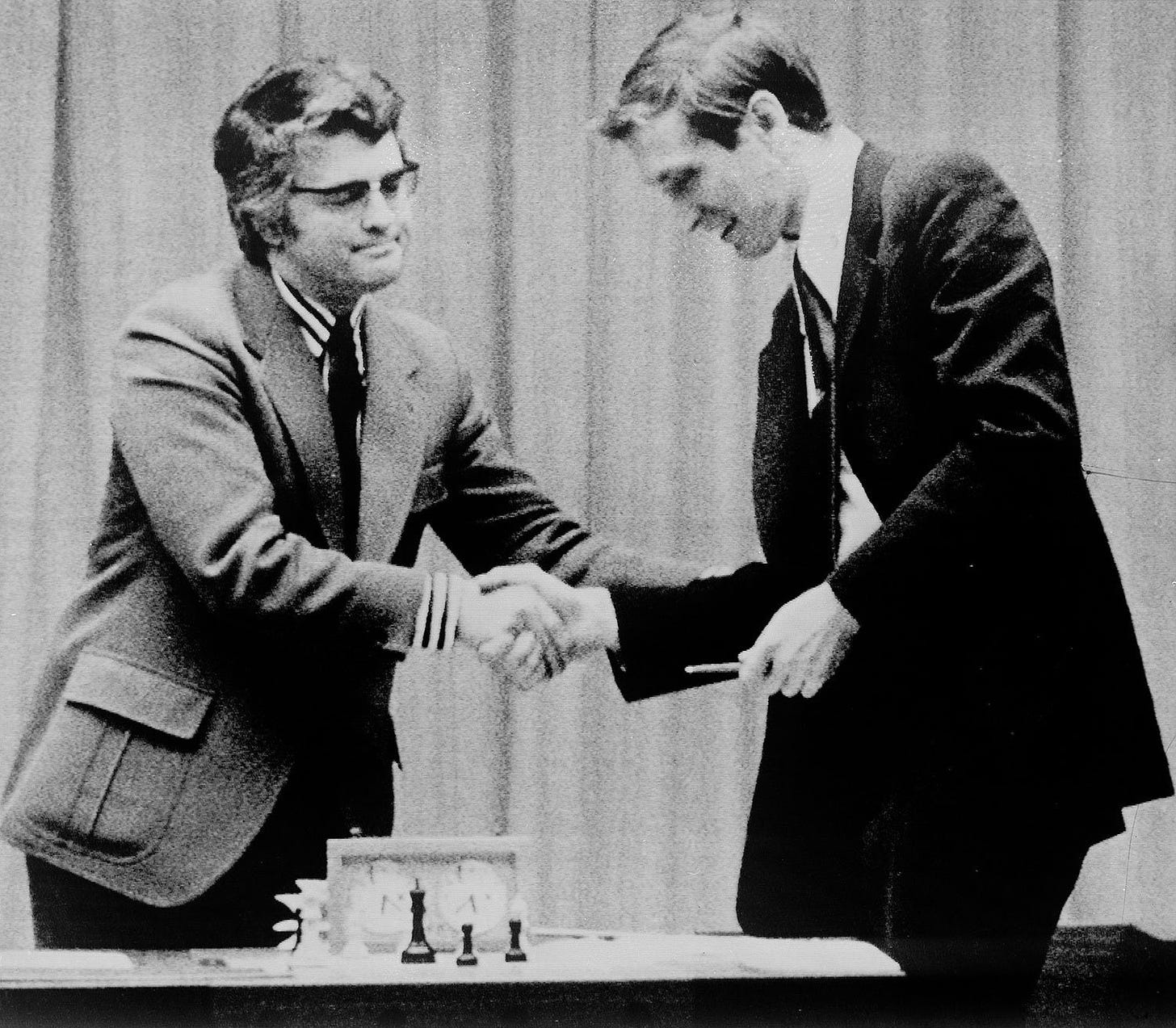

I’ve been very moved by a description of Bobby Fischer right after the won the Match of the Century in 1972 against Boris Spassky. Driving away from the tournament hall, all that Fischer could talk about over and over was how gracious Spassky had been in defeat. The real point of the story is that Fischer — probably the greatest player ever — never learned the main lesson in chess. He couldn’t bear to be defeated and so he never played again (or not for many years) and drifted into conspiracy theory-inflected madness. But when you learn to lose, you start to learn to be comfortable with yourself, and chess becomes something different from what it was in, say, the testosterone-and-acne-fueled college club. It becomes just something to enjoy as opposed to a point of pride, and something that — if the rest of life didn’t interfere — you really could do almost with interruption, forever. As Siegbert Tarrasch put it, in my other absolute favorite chess quote, “Chess, like love, like music, has the power the make men happy.”

I feel you man

I am not a chess player, and have not played any game except Old Maid as a child and a little checkers. So I'm suddenly in awe of what it means to engage seriously with chess. Thank you for providing me that entry point, Samuel.