There’s a startling moment in The God That Failed, the memoir of Osho’s bodyguard Hugh Milne, in which Krishnamurti is asked about Osho and replies that he is “a criminal.” What he meant, Milne clarifies, had nothing to do with legality. It was that Osho was in possession of certain mystic powers - above all an ability to exert a psychological hold over followers - and had used those powers for personal aggrandizement, to cheat people out of their capacity for their own decision-making.

There was something about the composure of Krishnamurti’s answer that stuck with me - the sense of a higher and ironclad morality. And the sense too that he was completely confident that Osho - a very different kind of person, a very different kind of mystic - had known exactly what he was doing when he overstepped some intrinsic moral law.

I’ve been thinking about that exchange as a kind of guide to a very fraught debate about morality in art. This argument tends to divide everybody into two disparate camps before they’ve even really thought through the terms of the debate - the camp of those who are fundamentally ‘ethical’ and socially attuned and who believe that art has its obligations to not increase pain, the same as any other activity; and those who believe in ‘art for art’s sake’ and no restrictions at all.

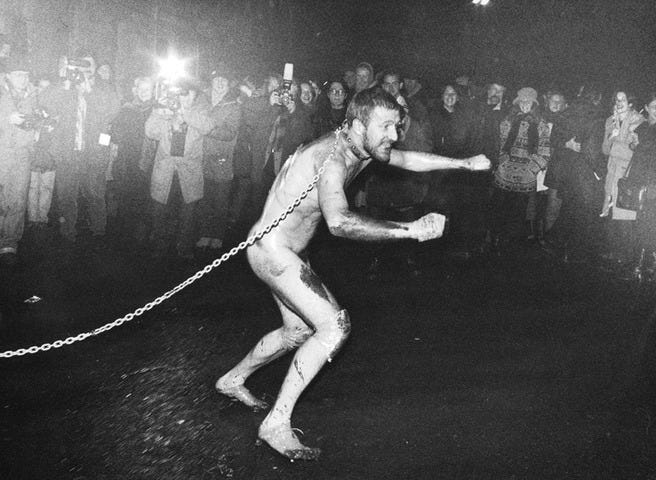

Here are a few examples from this tedious debate: Rebecca Solnit complaining about the unethical treatment Nabokov metes out to a fictional character in Lolita and wondering why the fictional character shouldn’t receive the same compassion as a living person; the confused friendship-breaking fracas of a woman writing a short story about a friend’s kidney donation, pillorying that friend for her self-indulgent piety; the man nailing his testicles to the Red Square as a demonstration of the extremes of art; the performance artist behaving as a dog in an art exhibition - to the point of chewing up other artists’ work.

Each of these examples generate their own furious controversy and vast incomprehension, since the ethics in any normal sense tend to be clear-cut (affairs with children are bad, betraying a friend’s confidence is bad, nailing one’s testicles to the pavement is at the very least painful, devouring other people’s art is bad) but art cuts a swathe through morality and seems to generate some sort of domain in which, for a designated period of time, within a designated space, ordinary morality does not exist.

Even a writer and intellectual as shrewd as Mary Gaitskill seems at a loss to find any vantage-point on these questions. In a recent interview she says - on the perennial subject of whether it’s ok to write about people you know - “If a person feels that even a handful of people are going to know that it’s them, and that they’re going to be harshly judged in a way that might affect their personal life, that’s something I would really hesitate to use. Part of me thinks even that should be usable because it’s art, and art is more important than anything. But another part of me is going, Argh! Really, is it worth it to inflict that kind of pain on another person?”

What’s interesting about a response like Gaitskill’s is that people who make art and are close to it tend to view artistic ethics as a thornier question than people who just consume it. Something about the behavior of the writer in the kidney-donation controversy, for instance, really bothers Gaitskill. “It began to seem like she wanted her to be an object of ridicule. And that’s when I kind of went, Unh-unh. She did actually do something wrong,” says Gatiskill. And it’s not just the betrayal of a friend, it’s that something about the act of betrayal itself demeans the work of art. The word ‘cheap’ comes into play here - the word that artists tend to fear more than any other apart from ‘cliché’ and ‘kitsch.’ The writer of the kidney story not only took her friend’s secret but she directly copied over emails that the friend had sent her. She sensed that she had a juicy ‘story’ on her hands and she didn’t want to ruin it with any fictionalization, any imaginative intervention. And Gaitskill - a truly superlative writer - clearly finds that something in there is the real ‘crime,’ the foregoing of imagination and initiative, the hoovering-up of somebody else’s experience without any sort of permission.

Cheapness means hitting the effect without bothering with any of the necessary construction - and for people who take art seriously that tends to mean that an unearned effect, however dramatic or memorable, would better not exist at all. In Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, there’s an extended discussion on why - on purely aesthetic grounds - it’s not really a good idea to hang a condemned prisoner in a hanging scene in a play. The audience, argues Stoppard, senses that something is off in the aesthetic rhythm, a spell is broken, an overly violent real-life event intrudes on a fictional dream, and the verisimilitude of it, the very striking unfeigned drama, does not compensate for the distortion of the play’s action. In the middle of the Satanic Verses drama in the late ’80s, Roald Dahl wrote a surprisingly bitter critique of Rushdie (and which really startled me when I read it in the aftermath of the Rushdie stabbing). “Rushdie knew exactly what he was doing and cannot plead otherwise,” Dahl wrote. “This kind of sensationalism does indeed get an indifferent book to the top of the bestseller list - but to my mind it is a cheap way of doing it.” Dahl’s point had nothing to do with ayatollahs or with freedom of speech. He was talking writer to writer. He believed that Rushdie was being cheap - and knew in his heart of hearts that he was cheap. He wanted the effect of alienating the Islamic faithful and wanted a worldwide debate on freedom of expression - none of which connected to underlying principles of art. For Dahl, the Rushdie controversy had all sorts of collateral effects - attacks on translators and booksellers, greater alienation between the Islamic and secular worlds, an impassioned defense of freedom of speech by the literary community - but underneath all of that, in the very core of the issue, was a cheapness on Rushdie’s part, an aesthetic ‘crime.’

The split in art right now is between an ethically righteous, woke art (with more than a hint of censoriousness for any work that does not abide by those ethical strictures) and art that is studiously amoral, in which anything goes. I’m more bothered by the first tendency - by the flood of saccharine art we’re dealing with and the implicit censorship that accompanies it, but the opposite trend has its own problems, namely that it runs easily into the trap of cheapness. If anything goes, if art becomes defined as that which is truly free and unhinged, there’s a tendency, especially when selling one’s work, to be as shocking as possible. That’s the basis of an artistic movement that I find epitomized in something like The Fleabag in which everybody behaves badly all the time, in which a bid for aesthetic ‘freedom’ seems just to mean that the characters, ostensibly inhabiting a recognizable reality, act in these oddly mechanistic ways, always making the worst possible decision, always perfectly, pathetically selfish.

There’s an obvious power in the art-is-it’s-own-domain position. What it’s really protecting isn’t so much license as risk and courage. What’s supposed to be so exhilarating about something like The Fleabag is that it’s such a self-portrait, that Waller-Bridge is taking a great, shameless leap for the sake of her art, exposing more of herself, making herself look much worse than anybody would ever present themselves in any other circumstance. The word ‘brave’ always comes up for work that’s so self-revealing - as in, “you are so brave to show so much of yourself.”

But everybody is kind of catching on that that sort of courage is a bit of a shtick. Memoirs always have this performative aspect, the memoirists pretending that it’s difficult to share their story, but that they must do it for their art, while their loved ones and the people depicted in the work tend to be genuinely horrified. I heard the story recently of a writer who very lightly fictionalized the character of a bartender in her novel. The novel sold, the novelist visited the bar thinking that all was well - the book was ‘fiction’ and it had been validated by the art world - and instead the bartender really vigorously chewed out the novelist for how she’d depicted her.

And, basically, the bartender was right. There was a frisson of courage and recklessness by the novelist in choosing to write so transparently about someone she knew. That sort of transgression is the kind of thing that makes crime thrilling - and it may have given a certain charge to the novel, a feeling of excitement that all of this wasn’t just made up, that it happened. (That’s the feeling that animates something like The Fleabag.) But at the same time it was unethical - it hurt the bartender and she wasn’t at all fooled by the veil of art. And, really, the writing in that novel was cheap, it relied on a few effects, a few settings that were clearly lifted straight over from lived experience. It was useless to pretend - as I’m sure the writer did talking to the bartender - that art had its own rules. Art actually does have ethics, and artists struggle all the time with questions about violating them (if I model a character on this person will that person be hurt? If I fictionalize this thing does it move it far away enough from reality?, etc). To violate those sorts of ethics means, basically, to be a criminal, a bad person. And there is a thrill in that, as there is in any crime, but it’s also something an artist has to live with in themselves - ‘art,’ at the end of the day, doesn’t serve as an excuse.

Sam, you raise essential questions for the novelist and the author of memoir. I believe the best works of art look inward toward the self. Betrayal of others for gain or notoriety is the 'story' at its worst. In Milan Kundera's _Testaments Betrayed_, Kundera says, "A novel's value is in the revelation of previously unseen possibilities of existence as such; in other words, the novel uncovers what is hidden in each of us." His comment may not directly address the ethical question you pose, but I do think it points us in the right direction. xo Mary

Sick