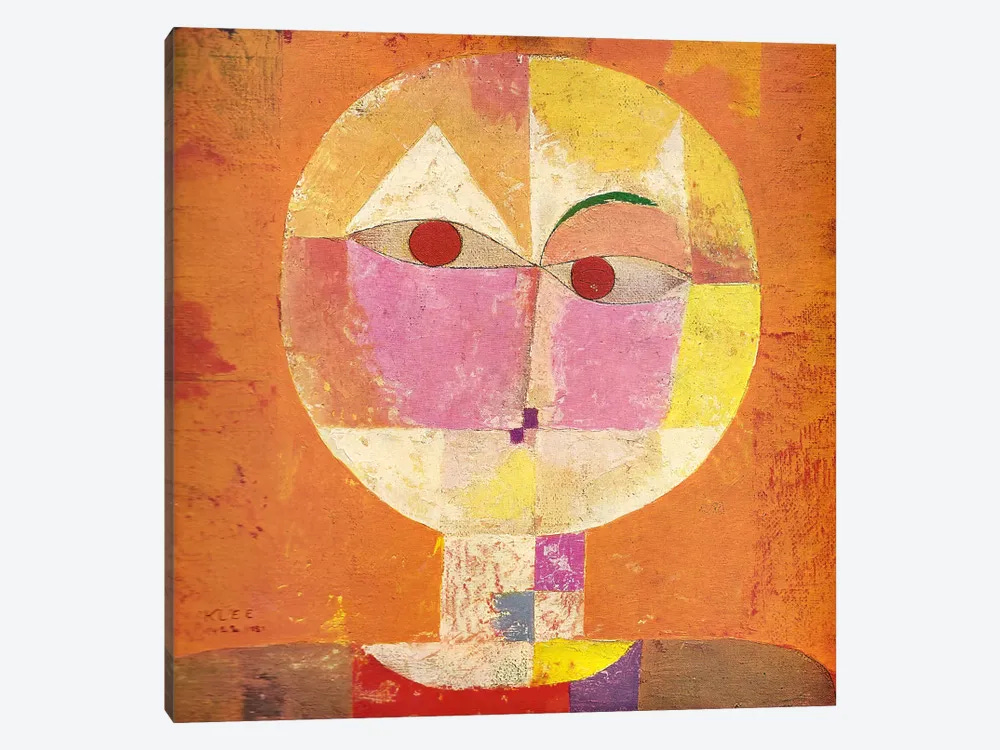

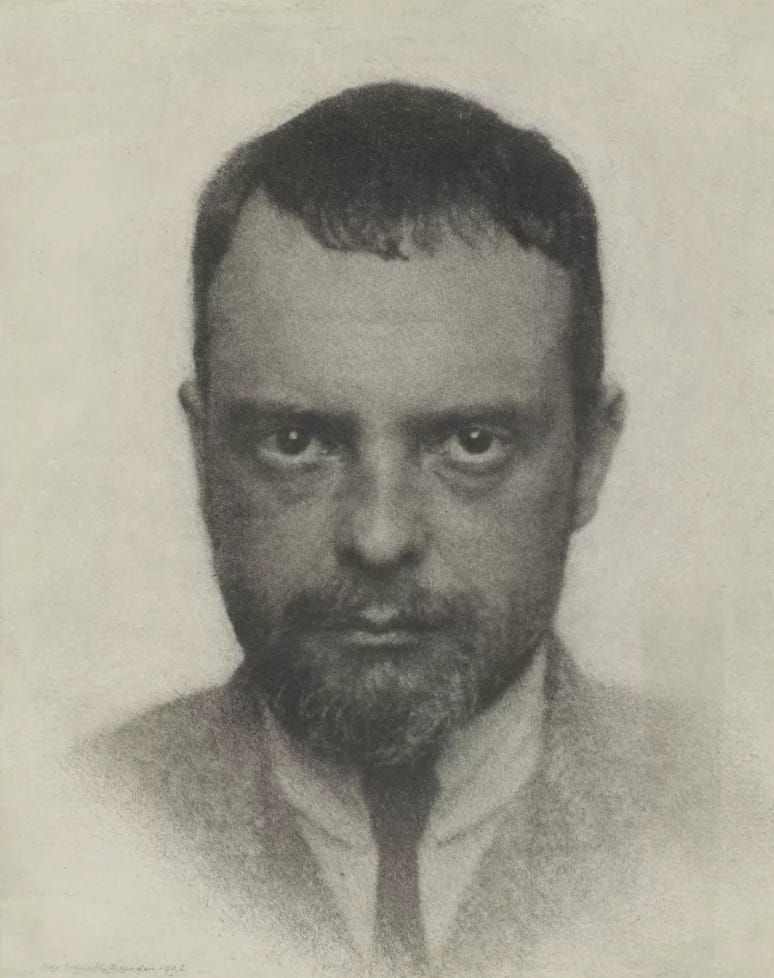

I remember coming across the stat that, at the peak of his career, Paul Klee averaged around 500 works of art a year - and thinking that that had to be a typo, or just not comprehending how that was possible.

That idea runs so contrary to how we normally think about art - that it takes time and care and craft and that if you do it quickly you do it shoddily. But Klee is understood to be a really great artist and the idea that he could make two works a day hints at something profound - that the way we think about the whole process of artistic production may be inaccurate.

For Klee to be that productive indicates, of course, that at some stage during his life he had clearly stopped thinking about his pieces of art as individual ‘works,’ that art had become something closer to just who he was, what he did. During that stretch and, really, for the bulk of his career, Klee got into a state where his hands and mind were always working, where he was always making something.

What I find odd about this sort of story is that it’s not usually seen as being exactly commendable. I imagine that most people coming across the stat of Klee’s productivity would get slightly dizzy thinking about it - the mind reels just at the amount of material that would have been used, at how Klee’s dealers would have had to contend with the volume of the work, although of course somewhere in there Klee would have realized that he had surpassed an output that could ever possibly be exhibited, that he was making work entirely for himself.

But if Klee’s busyness seems less than commendable, the question is why. I think the assumption is that anybody reaching that value of productivity would be compulsive, like Forrest Gump running across the country or Gloria in High Maintenance trying to set the world’s record for continuous dancing. But that seems not to have been the case with Klee. My sense is that he just deeply enjoyed what he was doing. Each piece was its own world, presented its own ideas to him and its own set of challenges - and he had reached a level of dexterity in his craft and confidence in himself that he didn’t sweat unnecessarily over them, he could trust himself to make the work. And my sense is that this sort of wild productivity is more common among artists than people realize. Simenon wrote five hundred novels while keeping up with, shall we say, a busy social life. Louise Bourgeois, Constantin Brancusi, Tennessee Williams seem always to have been making something.

The worlds of publishing and of exhibition curating tend to argue against this way of being. The premise is that a work being published, produced, or exhibited should be the result of a great deal of care - a large audience is taking care in seeing it, so it stands to reason that the artist should have taken care to make it; and the work is being selected as somehow special, as better than other people’s work and presumably better than other work of the artist themselves. But this often is simply not the case and for the prolific and the graphomaniac it can be a matter of indifference what’s actually exhibited - it’s like grabbing a specific mood or specific moment and insisting that that stands for the whole person.

The tendency of the curatorial types is to treat the graphomaniacs as anomalous or else to criticize them for debasing their art by making too much of it - that was the reigning critique of Williams’ later plays, for instance, that he had written them too fast.

But as I’ve gotten older and understand art better I’ve become convinced that the curators are basically wrong and the graphomaniacs basically right. There’s no fixed rule on this of course - some people work slower, some people work faster, etc - but the point the graphomaniac types make is that art is basically an extension of themselves, its purpose is for their own pleasure and only secondarily to show to anyone else.

I’m a bit surprised with the digital age, the work-from-home movement, etc, that it hasn’t caught on more the idea of basically making art continuously. There are glimpses of that in the crazed work cycles of professionals and even more specifically of the art grad school types, but what I’m talking about is a bit different. The pros and the grad school grinds tend to be careerist, the idea is to work very hard for a period of time and then to earn your leisure. The culmination of a youth spent making art is to not have to make art, to have your work celebrated, to lecture, to spend your money, etc. The Klee model, on the other hand, is to never stop - stop for literally nothing, success included; and for the work to become so smooth, so easy that it can be done continuously, so that a person becomes essentially externalized, expressed in what they’re making as opposed to being conceived always as an internalized potential that can be harnessed for work on a given object.

I am thinking specifically about this whole phenomenon because it seems to respond so closely to the undulatory feature of contemporary life. “The disciplinary man [in the old system] was a discontinuous producer of energy, but the man of the society of control is undulatory, in orbit, in a continuous network,” writes Gilles Deleuze in Postscript on the Societies of Control. That’s been a very lamented development. The feeling is that capital now, frictionlessly, takes over every element of a person’s life, that there’s no getting away, and that the old division in which a person is themselves some period of the day and a functionary the rest of the time has been dissolved - that people now are always and only functionaries. Byung-Chul Han is particularly good in embroidering upon Deleuze, in seeing even spirituality as an extension of capital. And the usual antidote is understood to be a reclamation of leisure time. In How To Do Nothing, Jenny Odell quotes Samuel Gompers, who hasn’t been heard from in awhile, in insisting that “we work for eight hours, sleep for eight hours, and have eight hours for what we will.” In the fight for the human soul this is seen to be the battleground - the need for leisure. And I am sympathetic to that but I just don’t really connect to it. Leisure, in my life, has tended to mean boredom, restlessness. It’s sort of crossing the picket line at the moment to look for ‘fulfillment’ from work - that’s management talk - but, really, where I’ve found fulfillment in my life is neither from ‘work’ nor ‘leisure,’ it’s from making things, from something closer to Klee’s sensibility. The important thing is to have autonomy over one’s work - and that’s an unbelievable challenge, the market puts so many obstacles in the way, and I have no solutions whatsoever for that other than the hard personal struggle to not be co-opted. But if one is able to achieve that, then the good life that follows from there is something like ‘working all the time,’ but working on one’s terms, working in a way that gives one pleasure.

Very interesting piece! When I think of songwriters (John Lennon as an example but there are plenty of others) I see them as being continuously watching and listening the world around them, perhaps unconsciously, and continually creating bits of lyrics and melodies. Perhaps not finished works in the case of Paul Klee but ongoing output. Writers continually taking notes for future use, etc.

Thanks for writing this!

Very interesting! Definitely not something I've thought about before.