Dear Friends,

This Substack will probably have more of a Central Asian feel for a bit as I share some pieces from a recent trip. It’s a very interesting part of the world — and I think all the more interesting for falling almost completely outside the American cultural frame of reference. At the partner site

, writes on the world’s oldest work of art.Best,

Sam

THE KYRGYZ ACADEMICS VISIT ALMATY

There is an academic conference in Almaty, Kazakhstan, and a group of Kyrgyz academics set off by car from Bishkek.

I’m not an academic, have no role in the conference, don’t really know anybody there, am not at all clear why I am in Central Asia at all, but I join the group — first, in the backseat, the mix of conversations between English and Russian, on the right side the white Tien Shan mountains, even taller and more majestic once we’re out of Bishkek, and then on the left side the steppe, stretching out to, as far as I know, Hungary; and, then, since I am the only male, Aigerim pulls her car over to the side of the road as soon as we are past the Kazakh border and asks me to drive.

In conversation, I’m told about languages. The Kyrgyz academics are liberals — they’re fond of the word “decolonization,” which hadn’t come up at all when I was here in the 2000s but is increasingly being applied to the turn away from the Russian sphere of influence. They speak English — English is seen as neutral, the international language — and they are patriotic, eager to switch from Russian, the lingua franca of the region, to Kyrgyz. Aijamal tells a story of another academic conference where, at a meal, everyone started, out of habit, speaking in Russian, and then Aijamal insisted that everyone speak their own language — the Uzbeks speak Uzbek, the Kyrgyz Kyrgyz, each language Turkic in origin and each one step of comprehensibility from the other, and “we actually did it!” she says. She has been working on a translation of an English climate change text into Kyrgyz — a real slog, given that most of the technical terms have no Kyrgyz equivalent — and the conference is a chance to get away from it for a bit. What’s unfortunate, she says, is that there’s a beauty to Kyrgyz that’s completely impossible to get in other languages — there’s a way that nature and human beings are interwoven in Kyrgyz that you would really have to know the language to understand; but, of course, nobody from outside ever learns the language.

In conversation, I’m told about the period of uncertainty in Central Asia, the various splits in identity. Aijamal growing up with a very gentle, very encouraging father, everybody else thinking that she should be working in the fields instead of reading, everybody else thinking that she was spoiled — “but now I see that this is normal,” she says. Aijamal telling the story of how, as part of her English education, she fell in with a group of Christian missionaries. And then, when they were close to sealing the deal, she had a dream of being in a store shopping for perfume and every bottle she picked up saying “Allah” — and deciding, when she woke, that she couldn’t leave Islam. And Aigerim telling the story of how her husband had gotten very Muslim, suddenly wanted her to leave work and wear a hijab. “No, I don’t want this,” Aigerim says in the way she says everything — at once very languorous and very determined, like somebody who has accidentally found themselves on the top of a mountain. So that meant the end of the marriage, and a split with her adult son, but also meant that she has this bustling work and social life and does things like head off to academic conferences every chance she gets.

The road is very smooth for a long time, and then suddenly it gives out. “Welcome to Central Asia,” says Aigerim, and there’s a long line of vehicles, the trucks bopping around like bobblehead dolls, and all of us passing each other and using both sides of the road, like bumper cars, for many long kilometers. As we get closer to Almaty, the highway is full of tree trimmers and road crews in orange uniforms. And then, as we pull into Almaty, we’re greeted by a traffic cop pulling us over for a ticket.

All Kyrgyz vehicles get stopped, it’s explained to me, because they’re older and the Kazakhs can fine them on emissions standards regulations. But Aigerim drives a hybrid, so the negotiation turns to documents. Aigerim and the cop talk for a long time in a hut. The cop asks her for 100. She says no problem and gives him a freshly-changed 100 tenge. On his handy calculator, he types the $ sign. Aigerim says she can’t afford that, she’s a teacher. This leads to a disquisition on the relative merits of the Kazakh and Kyrgyz education systems. Teachers are paid well in Kazakhstan, he says. But not in Kyrgyzstan, says Aigerim. She points out that we are on our way to teaching Kazakh students — 150 of them. He says he doesn’t care. She says we are there at the invitation of the dean of the school. He says that the dean can come to the traffic station and pay the fine. I’ve been intentionally kept to the side of the conversation, but now I remember that I have an International Driving Permit that may help — it’s something I bought off the internet when I was in Armenia, it may well be a fraud (there are websites warning against it), but in Armenia it was more effective than the actual AAA International Permit and, here, it works its magic as well. The cop is upset that it’s not translated into Kazakh, but now he’s really pushing things, and he consults with his boss, and his boss is equally taken with the permit, and we’re let off without a fine and there’s a feeling of great triumph in our car the rest of the way to the conference.

The conference is at the biggest university I have ever been to in my life — just a sprawl of a campus. It’s called Al-Farabi and it’s part of the overall theme of the Gulfization of Central Asia.

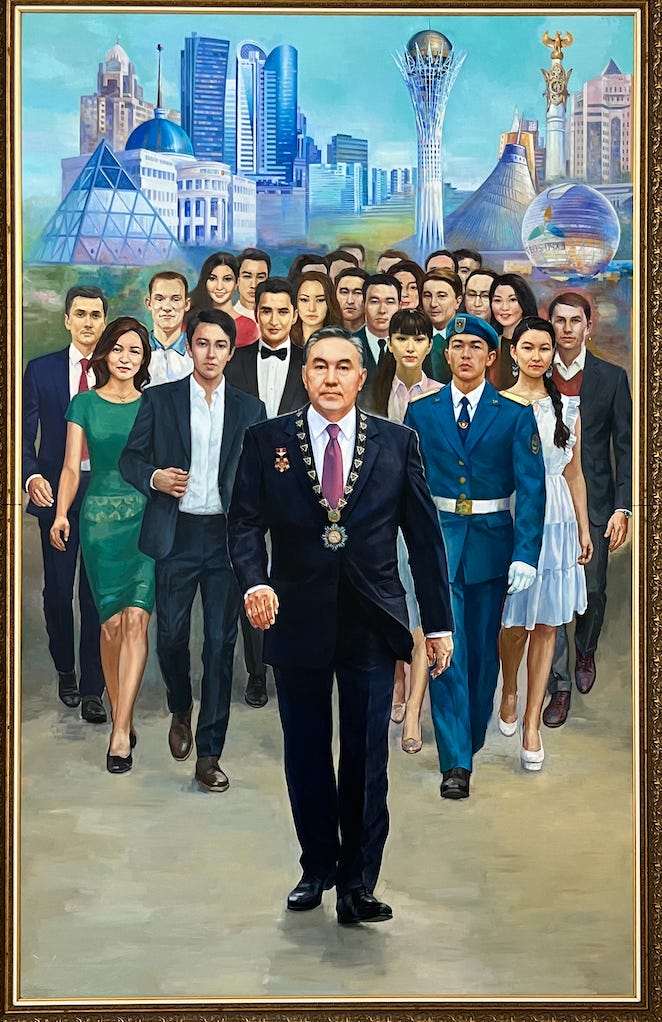

Gulf money pours in and finds a symbiosis with Kazakh oil and gas. There are two girls in Kazakh traditional dress who pose with all visitors to the conference. And, on the first floor of the building, is a mural on the history of science, with Kazakhstan (somewhat surprisingly) at the absolute center of scientific development — the narrative being that ties between the Arab world and the Kazakhs run back over a thousand years and the contributions of the Kazakh nomads made their way to the capitals of the Arab world. And, on the floor where the conference is held, there are many, many murals dedicated to Nazarbayev, the ex-president. He had been ousted by protests in 2019, and he had lost most of his statues, but he had kept his streets and had kept his murals at the university. There he was marching at the head of the Kazakh people, with a generous assortment of members of his extended family arrayed just behind him.

And there he was in a lab running Kazakhstan’s space program.

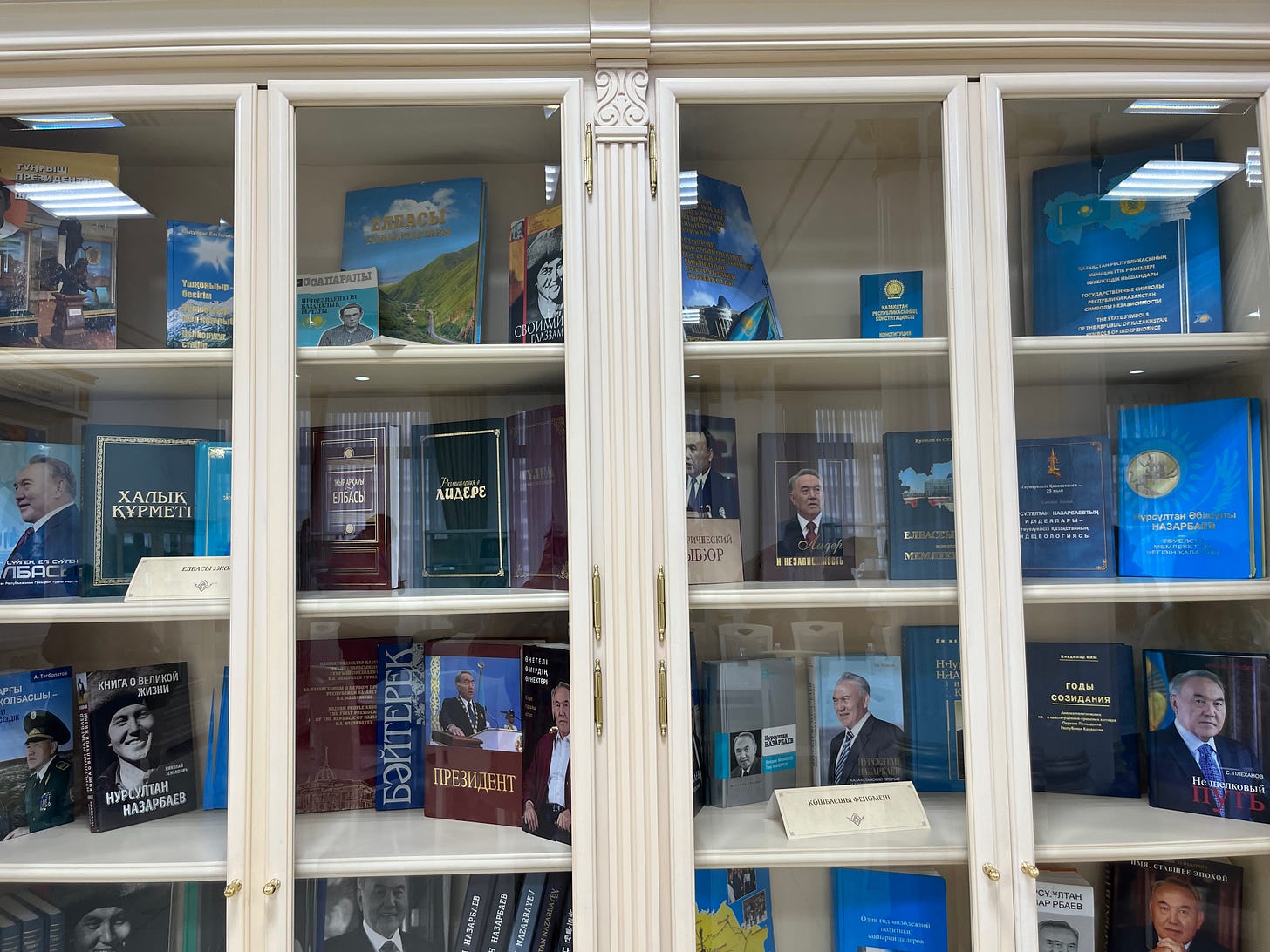

And there was a room in which the only books were books about Nazarbayev and the only photos were photos of him.

***

We all get bored of the conference very quickly. There’s a literary panel in the Nazarbayev room, in which I get some sense of what Aijamal was saying about language — a story translated from Kazakh includes the sentence, “the moon asked this tenderly, reaching out with warm hands and flying across a ravine.” And then Aigerim has different errands to run and asks me to drive her around the city.

This is a good opportunity to run down Kazakhs and Kazakhstan at every turn. It’s conceded that “Kazakhstan is ten years ahead of us” — all the gleaming buildings, the good paving on the roads — but this is outweighed by many other factors. “I thought corruption is better here, but it’s worse,” Aigerim says. We have the traffic cop to think about and the way the micromanaging host of our pensionaire keeps adding in hidden costs — a healthy extra fee for providing a receipt, for instance. There’s the difficulty Kazakhstan has had in letting go of its ex-president — the “three princesses,” the towers that he built in Almaty dedicated to each of his three daughters, are still dominating the skyline — and the way the authoritarian habit has continued. The city is full of posters for the 100th anniversary of the birth of the new president’s father — who is notable, as well, for being a founder of modern Kazakh detective fiction. Aigerim is incredulous. “The birthday of the president’s father,” she marvels. And, when we hit a real janga-like traffic jam, with an intersection completely blocked up and everybody placidly in their cars, Aigerim takes this as the last bit of evidence she needs. “This is why they can’t make revolution,” Aigerim says. “They are just waiting for someone powerful to come and sort it out.”

In the evening we have dinner with a Kazakh and that really helps to nail our case shut. He’s in a robe, has carefully-manicured facial hair and a student he brings around with him as an assistant. I don’t think he asks us a single question throughout the dinner. But he is, in his own right, interesting — lived in New York for four years, works as a cameraman and sometime director with Kazakh state TV. He is also in the military reserves and does shooting competitions with the special forces. He designed all the clothes and all the jewelry he wears — and he is very happy to give us the guided tour of his outfits. The jewelry is engraved with a runic alphabet, saying, “Tengri, please give me strength.” There are rings for his tribe, for Native Americans — who are widely seen in Central Asia as a “brother nation” — and for the Illuminati, for, as he puts it, “their very interesting idea that we are being watched all the time.” His conversation is all about history — the story of the Golden Man, who was buried in the 4th century BCE surrounded by thousands of golden ornaments and whose excavation in the 1960s sparked a sense of great resonance (“Kazakhs really love gold,” Aigerim tells me when we’re on our own), and the story of Kazakhstan’s long-standing scientific ties to the Western world, and the story of the revival of Tengrism in contemporary Kazakhstan as a counterweight to Soviet atheism and to Islam.

The sense is of a country really working to figure out its identity. And that’s the theme of the next day, when we skip the conference completely and visit Kök Töbe, with its theme park and its views of the city.

The tourists there are, I’m quietly informed, all Chinese — there are all sorts of business connections between China and Kazakhstan. The Russian influence is there in the language. The Western influence in some of the statues — a bench with all of the Beatles sitting and playing guitar; a replica of the Charging Bull and Fearless Girl, although, in Almaty, the bull is much larger and more muscular than it is in New York and is really terrifying. The Arab influence in the opulent mosques and universities — Aigerim is very unhappy to see a girl, maybe eight years old, already wearing a hijab. And then the Kazakhs really working to articulate who they are — Tengri, the Golden Man, the movie Nomad, the famous pride of the Kazakhs, which really drives the Kyrgyz crazy.

In the evening, we’re invited to a wedding — I have no idea who for, I never actually learn the name of the couple, but the idea is that, for a Central Asian wedding, more guests is always better. And more influences, too, seems always to be better. When we walk in, the guests are being led in a competition to dance to El Chombo, and then the music alternates pretty much evenly between slightly ‘90s-inflected American pop — the Macraena is very popular — and Central Asian music, with its more wrists-and-shoulders-based dancing. Everybody dances. The bride has her beautiful dance. The bridesmaids have their synchronized dance. The babushkas have their dance. The bride does a rap. It’s a wedding hall, so professional dancers rush in and do traditional dances and adrenaline-y Georgian dances with lots of kicking. It’s great, everybody’s very friendly and low-key, and we’re at risk of reconsidering our opinions of Kazakhs when it’s discovered that the bride’s family is actually Uighur, so no points awarded to Kazakhs after all.

And then Aigerim, who really is making the most of not being hijabed and house-confined, drives determinedly around the city looking for a night club and finally finds one, and it’s also really great, actually, a Russian band doing a lot of Victor Tsoi, and then there’s a lot of Rammstein, and some Central Asian and Arab music, and the bartenders are dancing when they feel like it, and there’s a guy on crutches dancing. And there is an edge to it — at one point, there’s a strip show, and the strippers, as kind of a prequel, lie on the bar with a crowd of men gathered around them and feeding them an orange, but it’s also not the feeling of anybody being knifed or anything like that, and it’s the feeling of Silk Road, like maybe the dioramas at Al-Farabi are onto something, like all possible cultural currents are passing through here.

***

And that’s the vibe as well the next day, when we give the conference an even wider berth. There’s a long lunch thrown by a diplomat friend of Anila, who is part of our group. She has some politics that I find questionable — “you have all these authoritarian friends!” Aigerim complains. In the past she’s worked for Aliyev in Azerbaijan and she received some kind of award from Putin himself — “he speaks so well,” she gushes — but the upside to that, I guess, is that she is well-networked. Her diplomat friend is very civil, as one would expect, and he’s very eager to debate the Ukraine War, but it’s one of these debates where, although we deeply disagree, we’re complimenting each other the entire time. And then we go driving up to the mountains and pick up another academic, a Frenchman, who, in the back of the car, is explaining how he discovered Heidegger as a teenager and that helped him through some massive identity confusion he had. And I don’t agree with the diplomat, and have no real comprehension of what the Frenchman is talking about, but there is this feeling I have that these sorts of conversations just wouldn’t be happening in America, that the cultural currents here are richer — and it’s the feeling as well that I may not be here entirely as a tourist, that this may turn out to be more of a central part of my life than I expected.

Our group finds a grassy spot on a hill and hangs out for an hour or two. “It’s like jailoo,” says the Frenchman, who’s learning Kyrgyz. “This is really nice,” says Aigerim, “this is a really good day.” And we all agree to that. And then, reluctantly, start the long drive through Almaty traffic and then through the unpaved part of the highway, with the trucks bobbing up and down, and then, perilously, through a really long stretch of road without any gas stations (a case of a little knowledge being a dangerous thing — since all I really knew about Kazakhstan was that it’s a petro state, I naively assumed that that translated to readily-available gas), and at our oasis of a station, the attendants change our tire pressure and wash our windows for free — as a courtesy for having “such beautiful Kyrgyz women” in the car. So our prejudices melt a bit yet again, and we decide that the Kazakhs in the countryside are ok and it’s just the ones in the city who are so unsympathetic and arrogant.

But, all the same, it is a relief to be back in Bishkek — the roads might be poorly paved, but there isn’t the same traffic. There’s a party at a karaoke club where everybody is singing their heart out — and then, somewhat surprisingly, the party shifts to a really flourishing gay club. So, yes, just better — everybody friendlier and more down-to-earth. Everybody happy to have visited Almaty, made friends, had experiences there, but no real reason to leave Bishkek anytime soon.

Names have been changed for this essay.

Fascinating. I’m jealous!!

There is whole world out there, a world of ideas, languages, battles, landscapes and prejedices differnet from ours.. and it can be fun, glorious and enlightning. Thanks!