Dear Friends,

I’m sharing some reflections on recent media layoffs and closures. I’m catching up on a bunch of different things and expect that for the next chunk of time I’ll be posting a bit more frequently but will try to keep the posts trimmer than I often am.

Best,

Sam

IT’S THE END OF THE MEDIA AS WE KNOW IT

Pitchfork…Sports Illustrated…Jezebel…The Onion…VICE

Well, it’s hard to fit all these into a song lyric (there’s something about ‘Sports Illustrated’ that’s just not melody-conducive) but the point is that it really is the end of an era, or maybe multiple eras. The near-simultaneous collapse last year of VICE and BuzzFeed News seemed to signal the end of the millennial media movement that burst into the internet circa 2010. Massive layoffs at Sports Illustrated and the Los Angeles Times signify something deeper — the effective end of a journalism model that has been around for a century and a half.

This is painful and takes getting used to. There is a great deal of online despair about Pitchfork. I’m sadder about layoffs at The Onion. But, fundamentally, these publications (the print behemoths in particular) were going against the grain of the times; their demise was more or less inevitable.

I don’t mean that in a rose-tinted technofuturist way, more in the sense that material conditions inherently change how media is disseminated. At the moment I’m teaching a history of journalism class and what’s striking for me is the extent to which virtually everything we think of as ‘journalism’ emerged in a very short period of time and on the back of the Industrial Revolution. That’s the characteristic mix between subscription and advertising in driving revenue, the frenetic pace of news-gathering, the consolidation of journalism into media conglomerates with wide circulation. But, even more that, it’s the taking-on of attitudes that were specific to that period. The mid-19th century was an age of ‘science’ and ‘objectivity,’ and the result was that journalism was stripped of the essays and attitudinizing that had characterized an earlier era and articles became as crisply written (this was no coincidence) as a telegraph wire. “The world has grown tired of preachers and sermons, today it asks for facts,” wrote Clarence Darrow in 1893. “News opinions should be free of bias or opinion of any kind,” pronounced the American Society of Newspaper Editors in 1923.

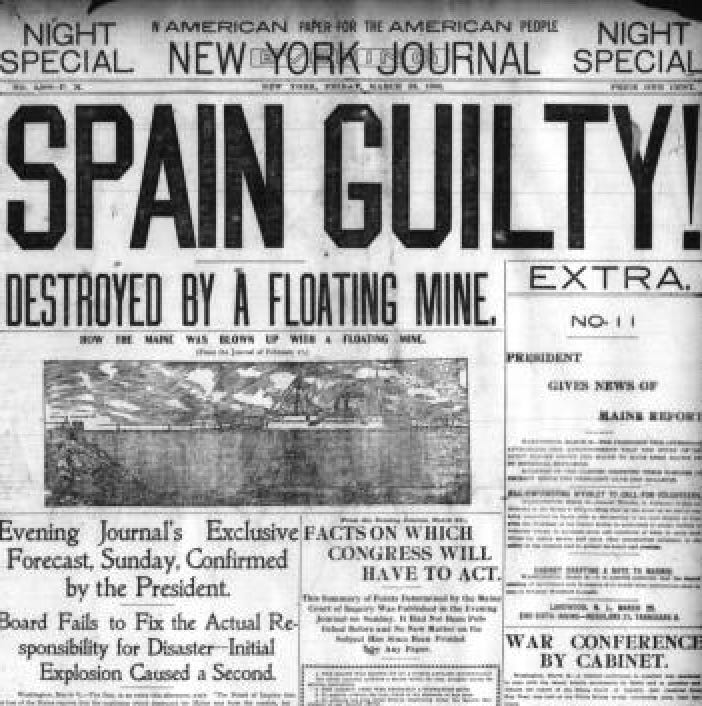

This development wasn’t necessarily an improvement, more a trend that got codified with time. From early on, there were skeptics who intuited that there were really was no such thing as ‘objectivity’ — that objectivity could easily be a mask for a particular slant. And these slants came to take on insidious form — as in the drumming-up of support for war with Spain by the Hearst media empire. The articles themselves looked like ‘news,’ but the effort was largely orchestrated by William Randolph Hearst, who wanted war for his own sundry reasons. The New York Evening Post, which was hip to what was going on, commented, “Nothing so disgraceful as the behavior of these newspapers this week has ever been known in the history of American journalism.”

That’s by way of example. The enduring legacy of the 19th century was the idea of a mass market, a homogenous public, that might all be attuned simultaneously to the same event — with the newspapers of the era bidding shamelessly for their greater ‘market share.’ The clever-boots analysis of what was going on comes from people like Benedict Anderson and Jürgen Habermas, who argue that this idea of the public was a highly contingent and sui generis event. Most societies in most parts of the world do not have the idea of ‘homogenous time,’ (which is a necessary precondition to the vision of the entire bourgeoisie sitting in parallel at their breakfast tables and reading the ‘morning paper’) and do not have the idea of a consolidated body politic bound together by a set of shared cultural assumptions (the ‘imagined communities’ of Anderson’s analysis) and for which the rise of mass media is instrumental.

Technological changes in the 20th century (radio, movies, and television) seemed only to reify this sense of the public as a homogenous mass — with a vanishingly small number of media entities able to seize a remarkable share of the public’s attention. The internet, on the other hand, is a technological change pointing in a very different direction: internet content is cheap to produce and is conducive to two-way traffic.

What this means is that the public that we are all so used to is effectively gone — or is so fractured as to be unrecognizable. If media from the age of the Industrial Revolution tended to identify itself in coordinates of place and time (‘The Los Angeles Times,’ ‘The New York Times,’ ‘The New York Daily News,’ etc), media now takes on a very different shape and identifies itself by affinity (‘Pitchfork,’ ‘Jezebel’) or, increasingly, simply by the personality of the internet’s new stars (‘the Joe Rogan Experience,’ etc).

This really takes getting used to. For well over a century, virtually the entirety of our civic and imaginal life — the thing to aspire to — was to be the person at the center of attention and to carry it off well: to be Roosevelt delivering the Fireside Chat to an attentive nation, to be Churchill with a few perfectly-chosen words willing the entire nation to fight. (The closing montage of The King’s Speech captures very well this sense of the unity of a nation with its mass media.) But those politely-assembled, fireside-hugging publics no longer exist — and in all the hand-wringing about ‘silos’ or ‘bubbles’ online is a more fundamental truth: that people have opt-in abilities that they never had before and can find communities of the like-minded without participating in the ostensible ‘center’ of the culture nearly at all.

In practical terms, what the idea of the cultural center created were a few megalithic companies bidding for their share of the market (The New York Journal vs. the New York World in the 1890s; CBS v. NBC v. ABC in the latter decades of the 20th century) and with a large number of middle-class jobs created downstream of that. That’s the cherished model of The Los Angeles Times or Sports Illustrated — all those jobs for writers, photographers, editors, fact-checkers, graphic designers, etc. It was a healthy business model and it should be mourned, but at the same time it’s worth understanding its limitations. That job security came with a price: talented, ambitious writers found themselves stifling their own voices, writing in standardized prose and with anodyne perspectives in order to fit the ‘brand’ of their publication (which very often meant aligning with the sensibility of some mercurial owner and of the ever eagle-eyed advertisers). Slant was ubiquitous and predictability the coin of the realm. (Incidentally, I don’t think it’s possible to write an inverted pyramid without some part of your soul quietly dying.)

There’s been a welcome looseness in media since the ‘60s and especially in the buzzy sensibilities of publications like Pitchfork or Jezebel, but a loosening of tone really takes you only so far in adapting to the currents of the shifting time. What the spirit of the new era would seem to call for is an almost total disaggregation — writers writing as themselves without institutional ‘branding’ and directing their work to small communities of the like-minded.

That’s what Kevin Kelly had in mind with his idea of the ‘thousand true fans.’ Substack is as close to materializing that as anything I’ve seen.

But it’s not worth pretending that Substack by itself has it all magically figured out. We’ve been doing it one way for about 150 years. There was much to be said for that system, but it’s not coming back. There is a great deal of pain to be expected in the period of transition, and I don’t know when or if there will again be a reliable professional career for a large number of writers as there was in the ‘golden age’ of newspapers. But the more important point is that that whole system was based on a particular conception of the ‘public,’ and the new, heterogenous, fractious public is, in critical respects, more interesting and more sophisticated, more attuned to its own desires as opposed to the propaganda of nation-states and of market monopolists. Whatever the future of writing (and of expression) is, it has to involve taking that heterogeneity of the public more into account.

The changing & changed nature of “the public” is an interesting concept with manifold repercussions that continue to play out. Thanks!

Great piece, as usual.

I think the dissagregation of audiences is also related to the rise of identity politics, which has been both a cause and an effect.

As the idea of a singular monoculture is deprecated, previously marginalized voices and audiences are served.

The conservative reaction to this is to force a return to a nostalgic idealization of a utopia with three tv channels, which is impossible, so they’re ironically becoming their own niche audience.