Dear Friends,

I’m fortunate to have several pieces out this week. I have a piece in

on how the Democrats can recalibrate their party; I have a splenetic piece in the on Rachel Kushner’s awful Creation Lake; and I chat with the estimable on ’s . I’m wrapping up my election series by pinning the blame for Trump’s victory where it really belongs….on George Washington.Best,

Sam

IS THE UNITED STATES BADLY DESIGNED, ACTUALLY?

I’ve been having this thought in the back of my mind for a while, and the result of the election kind of confirmed it for me. The thought is that the founders had a difficult job when they were putting together the basis for government and, in a word, they fucked it. That the U.S.’ system of government is overly baroque and that things have sort of been ok (although not always!) thanks to the extraordinary advantages the US had — two oceans for defense, a humming economy, and, for a time, nearly-inexhaustible land — but that we’ve done better than we deserved, and that Trump’s success isn’t a deviation from the system, that he’s exploiting holes in the system that were there from the get-go.

I should be clear before starting what this post isn’t. It’s not a claim that the United States constitutional system is illegitimate because insufficiently democratic — an idea that’s been kicking around on the left more than it should, and every so often shows up in a New York Times op-ed or even a Supreme Court dissent. A constitution is a precious document piecing together a fragile consensus. Maybe the single most interesting idea to emerge out of the Constitutional Convention process was Thomas Jefferson’s proposal of a referendum every twenty years, a sort of jubilee, in which it would be possible to draft a new constitution — but wiser heads were almost certainly right to reject the idea: the process likely would be bitterly divisive (it’s painful enough just choosing between two presidential candidates) and create a rift in the civil fabric. Like it or not, we really are stuck with the Constitution.

But if we peek under the hood a bit, we find things to be much more convoluted than the usual triumphal narrative skipping ahead from the Declaration of Independence to the Constitution would make them out to be. For one thing — and it took me until reading Joseph Ellis’ excellent biography of George Washington recently to put this together — the Continental Congress, in what should have been its shining hour, proved an embarrassment all through the Revolution.

As Ellis writes:

The mythological rendition of dedicated citizen-soldiers united for eight years in the fight for American liberty was, in fact, a romantic fiction designed by later generations to conceal the deep divisions and widespread apathy within the patriot camp.

If we analyze the Revolutionary War, we have to understand the following — that the Continental Congress had no ability to raise taxes or supply soldiers to the army; that the state governments, where power continued to reside, refused to approve new taxes; that popular support for the war declined, reaching a nadir by 1781, when a series of mutinies broke out across the army; that the success of the Revolutionary cause owed itself to three factors, Washington’s ability to keep an army in the field, the support of the French monarchy, and a lethargy on the British side that offset the Continentals’ own apathy.

As Ellis writes:

The heroes were not the mass of ordinary citizens, but rather a pathetically small collection of marginal men, the common soldiers of the Continental army. The main theme was not romantic but paradoxical; namely, the unattractive but irrefutable fact that the War of Independence had only been won by defying many of the values the American Revolution claimed to stand for.

The point was that not only that the Congress failed to raise funds or exercise leadership, but that the British were hampered by their own adherence to democratic norms — as Thomas Paine astutely observed, the war had outlasted Parliament’s attention span, and, after Yorktown, the British all but forgot about it.

The achievement of the Continental Congress during the war was to, after “five years of haggling,” finally ratify the Articles of Confederation. It’s a trip to read these — signed with all due solemnity, in the sight of “the Great Governor of the World,” and with the full expectation that there “should be no alternation made hereafter in any of [the Articles].” They read kind of like the Model UN resolutions that are dashed off before the delegates all disappear to pull PBRs out of the secret compartments of their backpacks and to give each other hickeys. There are stipulations banning states from issuing letters of marque to privateers — unless, of course, the state is “infested by pirates”; stipulations for the artillery consignment of each state’s militia; stipulations for welcoming Canada into the union.

What the Articles of Confederation represented was a kind of libertarian’s fantasia — with the vast majority of articles dictating everything that Congress could not do. The result was that Congress had no power at all, and the U.S. foundered throughout the 1780s, with Washington writing in 1786, “I am mortified beyond expression whenever I view the clouds which have spread over the brightest morn that ever dawned upon my country.”

That pessimistic mood led to a series of “behind-the-scenes” conversations aiming at a revision of the Articles — and, by the time of the Constitutional Convention, which was empowered only to revise the Articles, a faction had emerged intending to write an entirely new document. The Convention was a somewhat less-than-democratic affair, with no minutes taken in order to keep complete secrecy, with the windows of Independence Hall nailed shut in case any of the public should come prying, and with many of the delegates completely blindsided as to the real purpose of the Convention.

We have to acknowledge that the second draft of a constitution was better than the first, but if we cut the swelling music from the soundtrack, we might find ourselves skeptical of some of the framers’ decisions. The Electoral College was an obvious fuck-up — a bit of overthinking by the delegates that we’re still stuck with. The vice presidency — with its powers unspecified — was also a gaffe. The Senate may well have been similarly ill-conceived — another case of overthinking, with its labyrinthine rules leading, as Robert Caro was to write, to the “Senate becoming the negative power, the selfish power….an impenetrable wall against the democratic impulses.” Clever ideas like bicameral legislatures and ‘checks-and-balances’ are a bit less impressive when we consider that the delegates were mostly just following the British parliamentary system but, eager to avoid anything to do with Britain and intent on reinventing the wheel, dressed it all up in pseudo-classicism. The real checks-and-balance, of course, wasn’t so much the three-card monte trick of sliding power around between the different branches of the federal government but trying to find the sweet spot between federal and states’ authority. And that has been a vexing problem from that day to this — with, at the worst, the ‘states’ rights’ cause boiling over into the Civil War to, at the more trivial, that confusing moment in law enforcement movies when the local sheriffs suddenly have to start arguing with US Marshals or G-Men about who has jurisdiction — which is meant to be a metaphor for the absolute incomprehension everybody has when they’re trying to get anything done and have to figure out who’s actually in charge. But the really controversial point of the Constitutional Convention was the introduction of the office of the president. And, here, the delegates didn’t do what was most obvious — and what they assumed the solution would be for much of their deliberations — which was for the executive to emerge out of the congress, as occurs in most democracies without any evident problem; but, instead, under the guidance of James Wilson, to create a free-flowing executive branch, comprised of somewhat mysterious powers, with an inherent ability to expand immensely but based on a kind of gentleman’s agreement to never become a Caesar.

Once we take away the swelling soundtrack, we find all sorts of very reasonable misgivings all across the Republic. Charles Pinckney, hearing Wilson’s plan for the executive, called it “the foetus of monarchy.” The so-called Anti-Federalist papers — a collection of newspaper editorials opposing the Constitution — are, like the Articles of Confederation, a trip to read, since they telescope us back into a world before these compromises of statecraft had been sanctified by civics courses. To the Anti-Federalists, for instance, the ringing phrase “a more perfect union” was absurdity itself, and the pseudonymous “Brutus,” writing of the infamous three-fifths clause, opined, “What a strange and unnecessary accumulation of words are here used to conceal from the public eye. what might have been expressed in the following concise manner.”

Here, for instance, is how Elbridge Gerry — the father of gerrymandering — voiced his objections to the Constitution:

Some of the powers of the Legislature are ambiguous, & others indefinite & dangerous—that the executive is blended with & will have an undue influence over the legislature—that the Judicial department will be oppressive—that treaties of the highest importance may be formed by the president with the advice of two thirds of a quorum of the Senate—& that the System is without the Security of a Bill of rights, these are objections which are not local, but apply equally to all the States.

Comparing Gerry’s analysis to the state of the Republic 250 years later, not that much, to be honest, has changed. Congress has proved, often, to be wildly unpopular and susceptible to lobbying — exactly as the Anti-Federalists predicted. The executive, by a design flaw, had an inbuilt capacity to ignore Congress and carry out foreign policy entirely by decree — as has been the case at least since the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. For their part, the Anti-Federalists have been largely dismissed to history as a bunch of worrywarts (if not closet bigots), but, in a sense, they were the ones who had the last word — the Bill of Rights follows directly from their obstinacy, and it’s the Bill of Rights (which was unanimously rejected at the Constitutional Convention) that has become the enduring spirit of the Constitution.

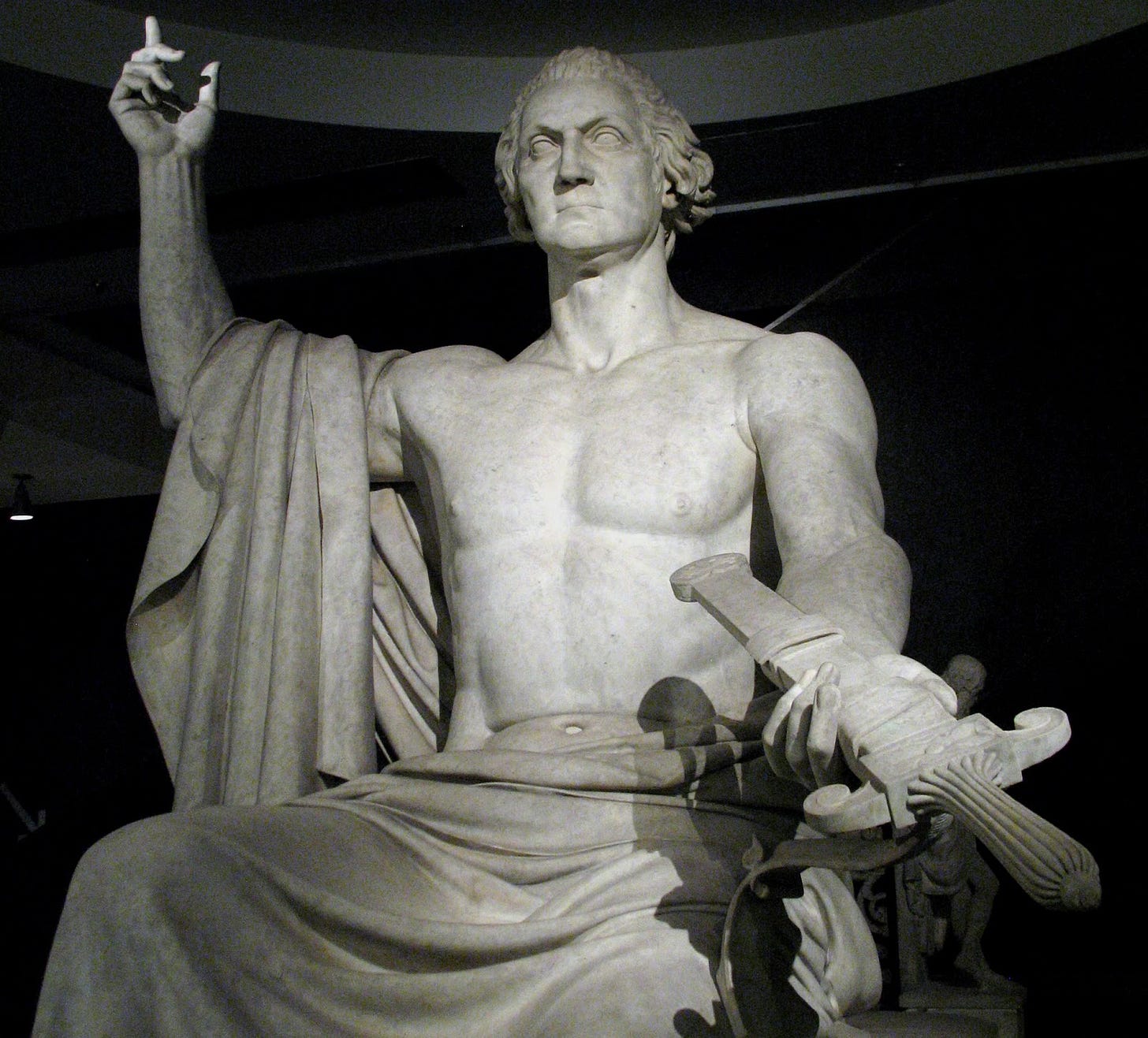

Any place I’ve ever worked, what’s become clear is that the institution is a reflection of the personality of its founder — and that this sort of psychological shadow can continue long, long after the founder’s presumed departure or death. In the case of the United States, the national government is basically — I’ve come to be convinced — the long shadow of George Washington. For the most part, this has been a stroke of immense luck — it was Washington’s doughty charisma that held the Continental Army together through the Revolution, provided the prestige for the Constitutional Convention, and, really, soldered together the national government in the potentially fractious period of the 1790s. The various ills that have befallen so many young democratic states were avoided in the US’ case because of Washington’s extraordinary character — he wasn’t power-hungry; he didn’t have heirs he would be tempted to pass off power to; he wasn’t part of any faction; he had, without especially seeking it, unchallenged authority; and for a military man he proved a capable and circumspect administrator. But Washington also was, in many ways, politically naive. He somehow thought that the United States political system could avoid splintering into parties — which was, of course, an inevitability. He somehow thought that the United States could entirely avoid foreign entanglements — which was similarly unlikely. He tended to place value in personal virtue rather than administrative logic — and in so doing created a model of the intentionally reticent president, which would not, needless to say, be followed by every other holder of the position.

We could say that the US constitutional system has done pretty well up to this point, but that’s maybe a sort of positive propaganda. Let’s not forget that the much-celebrated constitutional system utterly failed to solve the problem of slavery — which every other Western nation was in the process of outlawing. That the breakdown of the union into the Civil War was in many ways a systemic failure, with the judiciary stacked by the South, Congress falling into deadlock (and, for a decade, banning the discussion of slavery, which was all that anybody really wanted to talk about), and the war breaking out directly on the heels of a presidential election. Then, the post-war period was marked by massive corruption within the political system — with metastasized political parties out-competing each other to jam the ballot boxes and buy offices. It was a bad first century. The second century was somewhat better, but it saw the emergence of an administrative state — exactly what the founders had most hoped to avoid — that had no real checks on it, whether in the bloat of Washington’s bureaucracy or in the emergence of a shadowy overseas empire. The original problem, of the uncertainty over who was actually doing stuff, became magnified in the second half of the 20th century, with government outsourcing so many of its responsibilities to the private sector that government often seemed to vanish beyond the horizon of public accountability. As Robert Caro wrote of Robert Moses and of the administrative state in general, “The old system, imperfect as it was, was responsive to the public. The new system — Moses’ system — was not.”

As the old phrase has it, ‘fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.’ With Donald Trump elected twice and set to be the defining political figure of our era, it becomes harder and harder to treat him as an aberration — and it seems fair to suggest that he is more the embodiment of certain design flaws in the system. In terms of political vision, what he is arguing is surprisingly close to the original Anti-Federalist vision — tearing down the entire administrative state, undoing America’s foreign entanglements, eliminating taxes wherever possible, restoring sovereignty to business if not to the states. At the same time, though, he is exploiting a deep-seated ambiguity over the office of the president. In his much-mocked op-ed on the passing of George H.W. Bush, ‘Why We Miss The WASPs,’ Ross Douthat hit on something vital about the executive — that the office of the presidency is a kind of loose cannon, and its relative stability has been a matter of custom as much as anything, a genteel handshake agreement stretching all the way back to Washington. But, in its organization, there was very little really — no congressional checks, as in parliamentary democracies — to keep the president in line or to keep the presidential administration from going entirely in its own direction. Trump was exactly what the skeptics in the Constitutional Convention were worried about. It took awhile to come to pass, but now it has, and, unfortunately there are precious few safeguards in the system — at least for another four years — to keep Trump from doing whatever the hell he wants.

I keep meaning to *not* comment, but then you suck me in, Sam. Provocative as always, with the usual bold claims that make me wonder (foreign policy entirely by decree, really?).

I'll make perhaps an equally provocative rejoinder, which is that this is a very East Coast way of looking at things. The Electoral College sucks if you basically think that urban attitudes and populations matter most. There are large swaths of the country that presidential candidates would avoid entirely if it weren't for the EC. Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, the Dakotas, Kansas, Nebraska, and many more would be regarded as even more flyover than they already are. The result would also be a far less diverse slate of candidates -- you'd get the usual parade of Ivy Leaguers that you see for the Supreme Court.

I actually think that the people are the check on the presidency. If the people don't believe in public K-12, in vaccines, in empirical science (except when it helps engineering), or authoritative bodies like the CDC, AMA, or credentialing institutions like universities, then they cannot fulfill the check on a presidency that our democracy requires. In this case, who needs the Dept of Education if more people are homeschooling and then urging their kids to bypass college altogether? It's a climate ripe for snake oil, and the only remedy for that is hard knocks.

Interesting. If studying the history of US governance, its, in my opinion, to end the founding period with Jackson presidency and his successor Jacksonians, because the in some ways were strong centralizers (the nullification crises, etc.) but in other ways asserted and installed an ideological and accompanying governance framework that valued BOTH political AND economic federalism (the decentralization of banking and finance, etc.). This framework actually held until the advent of the so called Neoliberal Era, in fact, most of the biggest economic changes done in the 1970s and 1980s were not the undoing of the New Deal stuff but rather the undoing of the then ~140 year old Jacksonian stuff