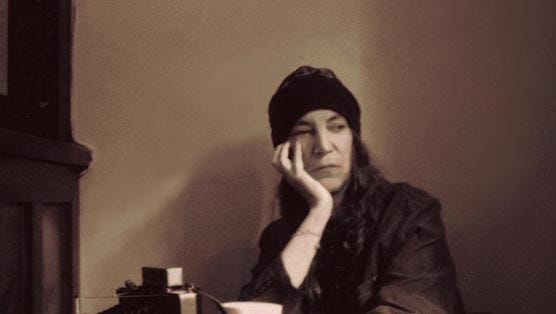

She was supposed to stay in Missouri while the divorce was finalized. It was an exile – ‘internal exile,’ that was the phrase she used for it – and she got a rented room in somebody else’s condo with army surplus blankets, there was no point in investing in anything else, and she walked along the highway to the Barnes & Noble, or a friend gave her a ride, and bought M Train, Just Kids, Seeing Is Forgetting The Name of the Thing One Sees. At home she went into a ‘deep dive.’ She went one artist at a time, Lou Reed, Patti, Nico, Dylan, Blondie. She kept the music down so as not to wake the woman she was subletting from. A lyric led to a Wikipedia article led to the references section led to google books led to a YouTube interview. It felt like its own art form, this kind of cruising around, the song in the background, on its low hum, the pockets of information, quirks of personalities hiding around the web. Well, if you were lonely enough anything started to seem like an art form.

Her lawyer called her up and summoned her to his office. He closed the doors, his table was impressively large and wooden – she supposed that that was meant to mimic class, status. He had several copies of the papers arrayed in front of him and in turn he pushed each one towards her. His hands reminded her of the elaborate flourishes of magicians asking you to choose a card. It was better this way, she thought, in spite of everything there was a wisdom to it, a lot of nasty events reduced to very clear terms, altercation, assault, battery, put that way they did lose a certain amount of their sting. He looked beatifically at her as she signed, everybody in law had this manner, they acted very proud of you when you did exactly what they wanted you to do. He had broad shoulders, a mustache that she was pretty sure he wore because someone had once told him he looked like Tom Selleck. They had gotten close as the divorce played out. She was familiar with the roundabout style of all of his jokes, with his whiskery breath when he leaned in to make a point. With an extra flourish he passed her a paper to fill out with her bank information, said that the wire would soon be on its way to her – although, of course, most of that would end up going to his fees. He went to get the door for her. Before he did, he ran his fingertips down her arm. He moved in to kiss and she leaned back. He didn’t lose his good humor at all. “You understand that I had to try,” he said.

The room she found in Alphabet City was in one sense a cousin of St Louis. It was a sublet, a kind of laundry space that had been outfitted with sink and stove and space for table. Something struck her as missing, as she surveyed the space in front of her, which, after all, was very well-priced for the neighborhood. “You could get a Murphy Bed,” said the subleaser helpfully and that struck her as absolutely perfect. Along with the clothes and documents that had made it out of her marriage and out of Missouri, she bought a Murphy Bed, a vinyl player, found a bookcase on the street and asked a guy on the block to help carry it up. She sat on the windowsill of her room with her rolled cigarettes and she listened to the traffic and the domino players arguing on the sidewalk and the music from the boomboxes they had with them and this was worth a lot, she thought, no more happy, no less lonely, but, really, worth a lot.

The divorce lawyer had given her the number of a friend of his in New York and he was in a way just a spruced-up version of her Tom Selleck lookalike in Missouri. He had less paunch, he didn’t make the mistake of moustaches or heavy jokes. He took her out to some kind of lounge space in Soho and it really was astonishing, this long factory-like warehouse of tables each one equipped with a modelesque woman in a tight-cut dress, each one equipped with a dude with cufflinks, blazers, slicked-back hair, enough cocktails and appetizers on the table as would make the right impression. Her lawyer’s counterpart took her hand under the table. “What are you liking so far?” he asked her. “What’s doing it for you?”

“I like the M train,” she said truthfully. “I’ve dreamed about it so long, sometimes when that happens the thing just dries up on you when you actually experience it, but that doesn’t – every time I take it, it’s everything I was hoping for.”

He nodded at her, like he’d always kind of thought that but had never actually found the right words to express it. She had the sense that he would be a very good lawyer, always keeping tempo with his client, with the court. According to his Missouri counterpart, he made an obscene amount of money.

She was by the East River taking in the view and she became aware of a couple kind of sidestepping around her. They seemed like elves, they were both very thin, they were smiling to themselves about something.

“We were trying to take a picture and to crop you out of it,” the girl said, “and then you looked so melancholy and so beautiful that we felt we had to include you in it – ”

“So she cropped me out,” said the boyfriend. He was used to being at the receiving end of their inside jokes.

“I hope you don’t mind,” the girl said. “We’ll share the photo with you if you want it.” She had a very beautiful old camera, it really looked like a face when Eve looked at it, the girl asked if she could do a quick shoot with Eve while the boy sat on a bench and looked at his phone and that’s what Eve thought about the whole time, how the upper circle of the camera looked like the eye of a kindly uncle and the lower circle looked like the wry smile of a sage and the camera’s shutter was like this sudden flirtatious wink, and she smiled back broadly at it. “You look so free,” the girl told her, “I think I could spend the rest of my life taking pictures of you.”

They went back hand-in-hand to rejoin the boy. “Days like today, this just seems like the best possible city,” he told them. And he was right – Eve felt he was absolutely right, he’d named exactly what she was feeling, the East River and a freighter moving along it like an homage to the time when the city’s whole thing was to be a port and Spanish people fishing and Hasids bobbing their heads at the water, doing whatever it is they did, and other couples taking shy pictures of each other, holding hands, but none of them as beautiful as Eve and her new friends.

And it was a disappointment to have to segue into normal conversation, it would have been better if you could do what you did at the end of a dance or a drug trip, just kind of swaying in place, a perfect silence. Which wasn’t to say that the conversation was boring, not at all, it turned out that he worked in publishing, even published poets sometimes. “He has a really good job,” the girl assured her. She seemed to be apprenticing for a role as some kind of New York maven. “If he likes something he’s usually able to get it published.” The boy sighed, rolled his eyes like there were office politics, complications that the girl couldn’t even begin to understand. He seemed to be apprenticing for a role as well – the weary professional, modest about his accomplishments, having done more than he could possibly remember. Music or weed would have been better, but this worked too, every sentence seemed to be an offer of something or other, the girl wanted to take a trip to the beach, the boy wanted to read her poems – when they were ready – the girl wanted to form a ‘club,’ most of the time when they met they would just lie on the floor of the apartment, the lights would be off, speaking would be banned, the only movement permitted would be for a designated person to flip a record to its B-side. “That sounds like the best thing in the world,” Eve said.

A variant of the art of the ‘deep dive’ took her on a walking tour of her neighborhood. Probably most people who saw her staring at a plaque or street sign assumed she was playing Pokémon Go or something, but that didn’t matter – that was the beauty of this place, you had to truly be eccentric, or extraordinary, before anybody gave any thought to you. She went past the flop where Charlie Parker had lived, and the apartment where Kerouac taped together his scroll, and the traffic island that William Burroughs said was his favorite place for shooting heroin. She went by a wall in the Village, next to a supermarket, which had Duchamp and Bogart and Ellington and everybody you could think of sitting around a smoke-filled coffee table, and that made her sad somehow, it wasn’t just that it was an attempt to promote a supermarket, it was that even in the drawing they weren’t really talking to each other, they were each in their own narcissistic thoughts, that’s how it was for great artists of course, genius always turned out to be a lonely thing, but it would have been nice if they’d a little bit more enjoyed each other’s company.

She went by a giant wall in the East Village that was painted to look like the ticket for a Blondie concert in 1979. She always had a sense when something portentous was about to happen, it probably came from certain childhood fiascos, it had stood her well in her marriage, she’d felt it when the sweet East River couple was tiptoeing around her, and she felt it now and wasn’t surprised to link it to a tall acned man with a guitar over his shoulder smoking a cigarette.

She asked him for one, which he gave silently, and asked if he played here. “Of course not,” he said. “This is like a bank or something. I’m meeting a friend.”

“Standing you up?”

He shrugged. Everything about his manner suggested he didn’t like to be teased.

“How long before you give up and have dinner with me instead?”

He shrugged again. “I like to keep my commitments,” he said.

He was persuaded eventually to take a phone number and for their date, or meeting or whatever it was, they went to his suggestion of a bar, which was a bust, ‘Long Island invasion,’ he said, and walked in a very haphazard route, through Wall Street and Chinatown and then back to the water, which led somehow, eventually, to his apartment. His seating options were not up to par and he tried half-heartedly a few poufs and recliners, offered the floor. “That’s what I do,” she said, “I like to sit on the floor.”

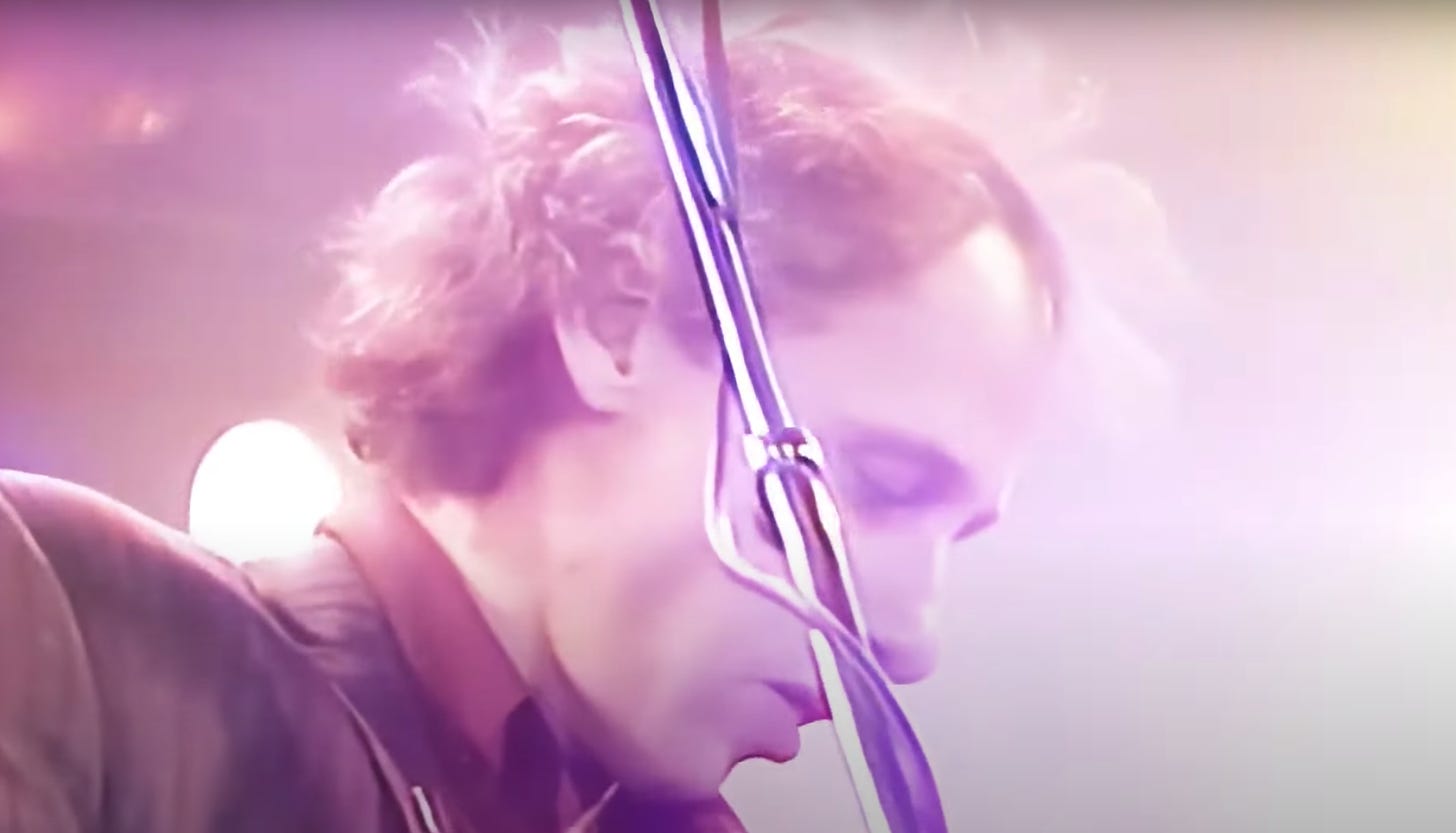

He had a synthesizer and he played a bit for her, a little mournfully, like he were at a church organ, and then he pulled out his laptop and flipped through YouTube links. There was a ritual to this, in another age people would have composed sonnets or learned waltzes, instead they played some video that had been important at one or another time in their life and sat patiently when the ads timed in and at some point in the very depth of the song he might hand her a new cigarette or the mason jar that they were using to ash. As she expected, and actually would have mandated, his music taste was very good, there were even a few songs she hadn’t heard, although it defaulted a bit to whiny Asaf Avidan. When it was her turn it was a tour de force. The real art to it wasn’t the songs themselves – everybody knew the best songs – it was to know the concerts, the recordings, to be in sync with the weirdos who posted videos to YouTube, the odd little montages they chose to accompany the music which had a certain basement poignancy to them, one raw moment on stage in CBGB or somewhere on the Lower East Side in 1972 and then the generations of loners paying tribute. It was the way Marc Knopfler kept wiping sweat from his brow when he played Brothers in Arms at Wembley

and you had to know that it was really meant to be Clapton’s showcase and he was supposed to pass things off to Clapton but you can see in his eyes, in the hand gesture, that he just can’t do it, he’s on fire,

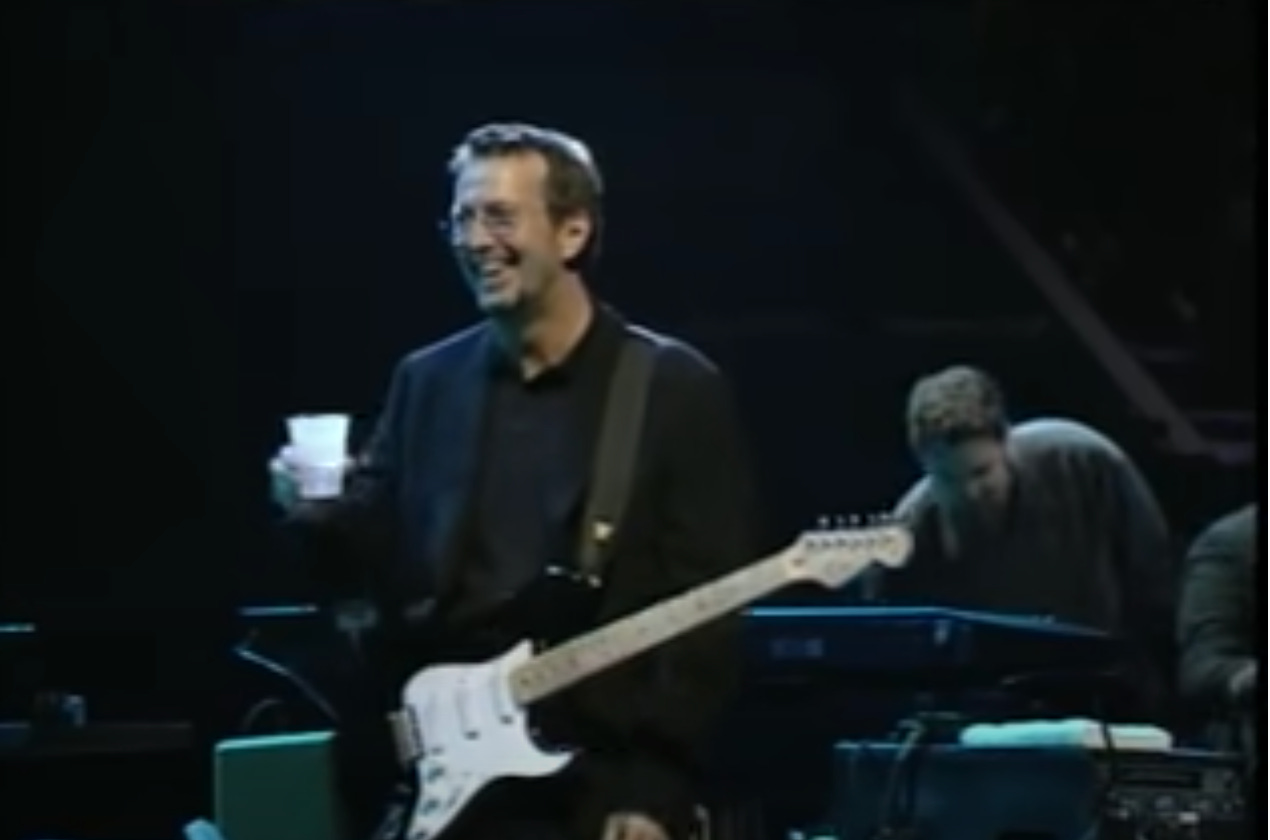

and Clapton is just marooned at the back of the stage;

and that was the perfect segue to Clapton at Birmingham, kind of a dweeby guy in his glasses, sipping water, just strumming along on his guitar for awhile, it was always so interesting the moment when these videos started,

and then he hits the opening riff of Layla and the guitarist Nathan East, who is a very underappreciated musician by the way, jumps back like he’s bitten by a snake,

but the main point really is Clapton’s expression, the set of his face, as he’s coming to those chords, not a dweeby guy with glasses anymore;

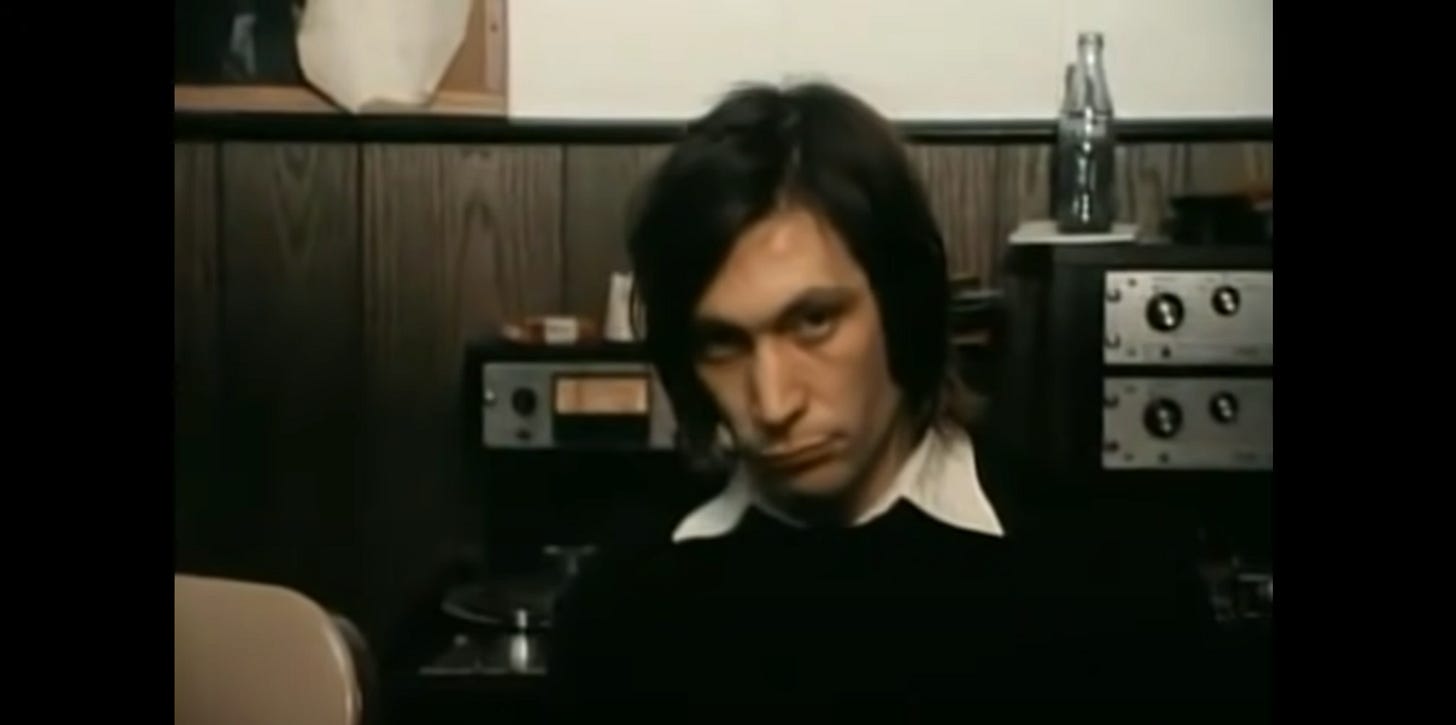

and then there are the Stones listening to Wild Horses all together and there’s something excruciating about watching musicians listening to their own music, Keith Richards is off in his own world of course and Jones looking haunted, maybe premonitions of his own mortality, and Charlie Watts looking just like a TV villain, maybe thinking about how he’ll help push Jones into the pool,

and you lose track of Jagger the whole time, he’s sort of a choirboy, emotionless, and then suddenly he does this little hand sway at the end and leads the applause and you realize that it’s him the whole time, it’s his group.

And apparently this was too much for Lou, her musician, which was the intended effect, and as she was explaining the band politics of the Stones, he put out his cigarette and slid across the floor and kissed her mid-sentence. And he did have an actual bed in his apartment, a brass bed, just like in Lay Lady Lay, and it was amazing that he looked a bit like Lou Reed and had the same name, as far as she knew nobody was called ‘Lou’ anymore. And after they’d fucked for awhile, which was good, he lay still, and then he kind of tilted over to the edge of the bed and curled forward and said, “Well, I’m going to hell for doing that.”

And then there was the long tangled description about the on-again-off-again long-distance relationship, the various restarts and fresh promises, and Eve actually had to laugh out loud. She knew more about hellfire than he did, more about its contrivances, she knew it to be more exacting than he could even begin to imagine. “I don’t think you can go to hell for a long-distance relationship,” she said. She didn’t want to hurt his feelings; she didn’t want to say that the hell she’d grown up with would swallow up just about everything from his lifestyle.

***

The East River girl, Julyne, called her up pretty regularly, wanted to go for walks, wanted to go on excursions. “We should make a film,” she said. “Have you ever acted?”

Eve decided to think about it like she didn’t know the answer. “No,” she said.

“But you’ve modeled?”

“A little,” Eve conceded.

“Well, it’s easy,” she said. “The less you’ve done the better, it helps to be natural.”

It was hard to keep track of all of Julyne’s plans, they seemed to contradict, circle around each other, she gave the impression of being completely whimsical, disordered, although in fact she had some sort of middle management position at a tech company. But it was nice to have a plan, however unlikely, it anchored Eve in the first couple of months, the temp assignments she took on, the clubs she went to, which always turned out to be the same thing, the sawdusty floors to sop up the beer and the fans with their tortoise shell glasses who bobbed their heads like they were in a jazz club, none of whom seemed, unfortunately, like the kinds of people who would start fistfights outside or fuck each other in bathrooms, and the musicians pretty much exactly the same, the style seemed to be softcore arty, like everybody was in the math club but also had a band, they all seemed like such nice guys, really knew the music on a technical level, she always had the feeling whenever she went that it had been good for her somehow, like a sound bath. The Tinder swiping that took most of her evenings, the mix of starter lines the guys used, some of them just ineptly asking what her interests were, what she liked to do for fun, some of them spinning game, asking her to close her eyes and picture her perfect happiness; maybe dating would have been more enjoyable if she hadn’t seen The Mystery Method on VH1. She complained about it to Jeff the lawyer. He had his really admirable quality of shaking his shoulders forward at each of her good points, agreeing vociferously like she had just cracked the case or something.

“I think it’s like this city got so high for such a short period of time that it had to come crashing down,” he said. “It’s like an iron law, it’s like gravity, forty years of mediocre after the high point.”

“Fifty,” she said, and they started arguing about the exact moment when the downfall had started. For a lawyer, he really was very smart. He was hip to things, when he took a break from agreeing with and impressing her he had surprising, interesting opinions.

Unexpectedly enough, the movie did materialize. Julyne’s idea was that Eve and Gabriel, her boyfriend, would be a couple, she claimed that they looked alike, they would be like brother and sister going through relationship problems, and then another character, which wasn’t specified but might turn out to be played by Julyne herself, would intervene and break up the relationship. The theory was that things could be shot very cheaply, sort of the way Warhol and Edie Sedgwick had done it, and, sure enough, a cameraman appeared with a very huddled style of shouting, and mic’d up both her and Gabriel, and they had a long walk along the waterfront in which they were meant to chat and argue while the cameraman swerved and spun around them like a paparazzo.

At a break in the filming, while Julyne and the cameraman were running off to a Chinatown shop to pick up some piece of equipment, Eve and Gabriel lay down in the grass together. They were in one of the scratchy parks by the East River with all the grass in patches. They had been walking along for so long as a couple that it was completely natural to lie down together, Eve resting her head on his shoulder and Gabriel running his fingers through her long hair.

“I’m very sorry I haven’t read your poetry yet,” he said.

She told him that was fine – she knew how difficult it was to read anything by friends.

“I thought working in publishing would inure me to it,” he said. “I’d just read – but there’s something about seeing a piece of writing in your inbox and knowing it’s more than like a stupid article or listicle and not having a boss breathing down your neck telling you to read it, that just makes it completely impossible. I don’t know why it’s so difficult.”

“What do you think it is?” Eve said.

“I think it’s the danger that it might be good,” he told her. “A piece of writing can really change you. Most of the time I’m stressed or something, I’m not in the mood to be changed.”

He was pressing his fingertips along her scalp, she had the feeling that he wanted to kiss her. Instead, they talked about something having to do with the production. “I know this whole thing probably seems insane, just kids pretending they’re auteurs,” he said, and then he kissed her. He was very cute, he had curly hair, which she had long ago decided was her type, and he could be smart and funny, his self-absorption had a certain charm about it.

“I’m sorry,” he said when they’d hit a break. “You’re probably tired of people making a move. It’s just – you’re so outrageously pretty, I don’t know how anybody can not.”

***

Lou had paused a few days after their date before messaging her. She was attuned enough to this kind of thing that she had a kind of heightened awareness of each moment he didn’t text, felt his Catholic schoolboy guilt churning away inside of him. And then, after about three days, he texted to say that he was going for a walk to ‘clear his head,’ wanted to see if she would join him. That date, like all second dates, was a pale facsimile of the first time. They went for a walk along roughly the same route. They found their way back to his place, although now she noticed that it wasn’t so charmingly haphazard, it really was all deliberate. They had the same mini-party on the floor, they smoked and watched YouTube clips. On their route they had gone by the Blondie wall on Bleecker, and Eve – who had used up her A material on the previous date – put up a bunch of Blondie’s music, there was Debbie Harry walking down the Lower East Side for the music video for Rapture and jesus that looked dangerous, she looked like she was about to get knifed any second,

even though that was a few years past the point when, she and Jeff agreed, everything had gone downhill, and there was Gravity from the Pollinator album and Harry in her shades exactly like an extraterrestrial just making a pit stop in the East Village

and the drummer just fritzing out like he was a human alarm clock or something,

trying to get through to her somehow, trying to bring her down, and it was just such a great question, wasn’t it, the question, ‘what is it that makes the world go round, is it love or is it gravity?’ Lou smoked and watched very petulantly. “I don’t know,” he said after she’d finished her little playlist. “To me they’ll always just be a pop band.”

When it was his turn he froze at the computer for a long time and she found herself really wishing that he’d open up GarageBand or Spotify and there would be something special, something unexpected, a song written just for her, Lou playing his first-ever set in the city. Instead, he went to YouTube and put on ‘Maneater’ in the Lower Dens cover. It was a good song; she had it on her Spotify favorites. He seemed to make a point of lighting up a fresh cigarette as the song started, watching her the whole time. What was he expecting exactly, for her to crumble, for her to break down in some kind of remorse? How brilliant, how original, Lou, who probably, truth be told, had been in his high school’s math club. She made a point of sucking on her cigarette, staring dutifully at the screen, as enigmatic as Charlie Watts during Wild Horses plotting the drowning of Jones in the pool. She’ll only come out at night the lean and hungry type Nothing is new, I’ve seen her here before.

She had the sense of passing some kind of test. Whatever it was that Lou wanted to prove seemed not quite to have been expressed. At the right pause in the conversation they maneuvered to the bed. After sex, he didn’t vault up in the bed filled with contrition for his girlfriend in Cleveland, but she slept very poorly, aware of his sweat, of the sighing way he kept turning over on his side of the bed. In the morning she walked through the East Village in her pencil skirt, which did in fact look slightly like the girl in the Maneater video, and it was all Polish shopowners pulling up their grates and hipsters with messenger bags trying to coordinate their coffees and their Citi Bikes. She paused by the Blondie wall on Bleecker and texted him, “I’ve done it both ways, I’ve done it your way and I know there’s nothing there – nothing for me.” And he took awhile probably to heat coffee, to splash water on his face, before he started sending back his annoyed, arguy text messages, but there was nothing for her really to add, she’d made her point.

***

She and Gabriel by this time had a thriving text message chain. It was mostly about random things that happened during the day, an argument at work that reminded him of an argument he was having with Julyne when they were shooting. He asked if he could read her poetry. “You have a whole book of it!” she texted.

“Not that,” he wrote. “Like a tease, a tease of your poetry – to make me read the book.”

“Here’s a haiku,” she wrote him.

Very dirty old man

Chrysanthemums sing in spring

Matters not he’s young

He told her it was an excellent poem and if everything in the book was like it, and only if, he would be willing to read.

“Fortunately,” she wrote, “it’s that poem over and over again.”

“Perfect,” he told her. “You’re clearly a real poet. And, as you know, haiku master, the cherry blossoms are in season. If you ever want to see them, let me know.”

And she wasn’t necessarily averse, any more than she had been when he kissed her during the break in filming, but his game could use some work – literary types always just wanted to show you that they knew words, could make references, their chat was always full of these calling cards – she figured that the right way to handle this was to ice him a bit, make him reflect on his approach, maybe help him to improve in the future.

The trouble with icing people – as salutary as it might be – was that it sent you into enforced isolation. Her current deep dive was taking her into the singer Nico, and it was just astonishing how Nico managed to do everything wrong that a person could possibly do wrong, the scented candles in the dressing room while the audience was getting restive and Reed was having kittens onstage and the habitual off-keyness of her singing and the racism and the broken-bottles attacks against black people, and none of that mattered, it was so interesting to imagine a time when none of that mattered, at least not for Nico.

A very interesting deep dive, really, one of the best, since it made all these other people, Reed and Brian Jones and Jim Morrison, seem like such squares, like they were just nerdy kids, professional roofers, who somewhere or other had learned to play the guitar, and floating above all of them, superior to all of them, truly at the center of it, there was Nico, tone-deaf, out-of-key, batshit crazy Nico.

An excellent deep dive, although, to be fair, she could have conducted it just as effectively from the condo room in St Louis.

***

Her ex called her in the middle of it. She was pretty sure she had blocked his number, his facebook, all points of access, but, apparently not, there were all these loopholes for telemarketers, maybe there was actually no blocking anybody at all.

“You got the wire?” he said.

She had to laugh. That was months ago, he had signed the papers for the wire, he had seen it leave his account, but that was him – everything careful, everything deliberate.

She confirmed that she got it, she would be eternally grateful to him for sending it, etc, etc.

There was the pause in the conversation, the way there always is in these circumstances, the gathering of forces, the clearing of irrelevancies. “You said terrible things about me,” he told her.

“You had every opportunity to challenge them.”

“I’m not – ” he said. “I’m not the kind of person who fights bare knuckle.”

“To the contrary,” she told him.

“I’m not – ” This whole thing must have been a nightmare for him too, it was the kind of thing she was supposed to consider, that was part of her upbringing, part of the marriage covenant, but the beauty of people like the Tom Selleck lookalike was that you never had to deal with that side of it. “I wanted to say that I made the concessions I made, I wanted to say that there were times I acted very poorly. I wanted to say – ” she started to feel like the whole thing might have been rehearsed, like some kind of amends speech, she hoped for his sake that he didn’t have a handwritten paper that he was clutching, tremblingly, in front of him. “I wanted to say – and I didn’t feel like I had the opportunity for it before – that you were a good thing in my life, no matter what else happens, no matter how far apart we are, the day I met you, I day I asked you to marry me, those are the happiest days I’ll ever have – ”

She was right to be suspicious. She could see the paper trembling, the hand of the pastor who would have composed at least one of the drafts. She let him talk it out; as he did, she read about Nico’s comeback with Siouxsie and the Banshees.

As far as her suitors went, Jeff the lawyer had the best game. He texted infrequently, he was shrewd enough to let threads lapse sometimes right in the middle of a conversation. And then he would ambush her suddenly with “Plans for the 4th? Bahamas?” or “Biz trip L.A. Come with?” And she knew better than to accept any of Jeff’s gifts, the hidden usurious costs that would be on the other side of them. But he changed tacks, wrote, “A little low this week. Misery=Company?” And that was right, that was the tone she was after. Her ex, somewhere in the very depths of the sad sack monologue, had said, “And how is it in dog eat dog city?” and that was the trouble really with anybody you had known for a long time, the way that anything they said, no matter how unintelligent, inadvertent, anything they said, just by the shift in tone, the covering what they really meant, could dig away at you. And by a certain inexorable emotional logic that meant Jeff, that meant that Greenwich Village brownstone, the oddly deferential way he answered the door like he were pretending to be his own butler, the roasted vegetables in the oven, the fish on the stovetop, all ready to go, like the chef had slipped out the bathroom window the moment she rang the doorbell.

And it was very nice there, he had a really gorgeous VPI Prime Signature turntable, and a nice vinyl collection featuring a lot of Motown but with her favorites all pretty well represented, and he put on a good show serving her dinner, fully equipped with oven mitts and doilies, and a bottle of white wine that he poured waterfall style and that she could only assume was very high in tannins or whatever it was that mattered there. The feeling was of being around a cultivated Goth who had moved into one of the very best of the Roman villas.

Just as they had finished preparations and were sitting down to dinner, this being the way of these things, her phone started to blow up.

“Boyfriend problems?” he asked her.

She shook her head. She wasn’t quite sure how to interpret the text messages she was getting. She thought it might have to do with the film, Julyne was asking her very specific questions, Julyne abruptly got very dictatorial when she was directing, they were questions about where she had been at a specific day and time, and it seemed reasonable to assume that she was being interrogated about a lost prop or footage that had gone missing, not that she had ever been trusted around the footage.

“Trouble in teenybopper paradise?” Jeff said.

She did feel that she was being rude, and spoiling all the work that Jeff, or a vast Mexican kitchen crew, had put into this, and texted that she was having dinner and she would respond later.

“That’s the thing,” Jeff said, “there’s a certain phase of life that’s just drama, everything is drama, there are people who get stuck in that forever, it’s like an addiction they have.”

“Marianne Faithful spent her whole life with Jagger and that entire time all she could think about was the one night she spent with Keith Richards,” Eve said. “Does that mean that all the Stones were was addicted to drama?”

Jeff shrugged. He had his wine held in front of him in a commanding posture. “Some people are geniuses,” he said. “It’s great to be a genius. If you’re not a genius, it’s a good idea to figure that out.”

She had tried to stamp out the text message chain, which was still escalating, and now her phone was ringing. She canceled the call but it rang again and she felt she would be callous or something to keep ignoring so she picked up, wandered out of the dining room and through the house. Julyne was suppressing tears and shouting into her ear. She went through a living room lined with paintings that looked like they might have been by Keith Haring or Basquiat,

went through a room, with a medicine ball and record player, that seemed to have no specific purpose at all.

“I mean, did you think about telling me?” Julyne was saying. “I mean, did it occur to you that we were friends – that this was the kind of thing I might want to know about?”

It was strange, even in the munificence of the house, the right place to take a call like this was in the bathroom, so that’s where she wandered to, sat on the toilet, even though she didn’t have to pee. The bathroom walls were lined with tasteful photographic nudes. “Did you meet up with him?” Julyne was saying.

“No.”

“Why didn’t you?”

They had really had a nice friendship, she and Julyne, everything very easy, everything, as per Julyne’s style, pushed off into a hazy, amorphous future where anything was possible. A relationship with a woman? Might be interesting, had never tried it before. Kids? Sure, one or two, but only after a long list of accomplishments had been ticked off first. Now her voice was as precise and staccato as if she were badgering a witness.

“I don’t know Julyne. I wasn’t interested. I didn’t think he was really my type.”

“Then why did you let him kiss you?”

“What’s worse, that he was interested in somebody else or that he was rejected?” Eve said. “I’m not sure which one you’re upset about.”

“I’m upset about everything,” Julyne said, and that was the screech, the aggrieved screech. The nudes on Jeff’s bathroom wall were sardonic about it, they were models, some of them probably semi-prostitutes, they had been abused, hit on, bought and sold, as a matter of course. She wasn’t sure where they were from, if this was Jeff’s photography hobby or, more likely, another investment undertaken with undue seriousness, another gesture in the direction of art. In any case, they were all united on this, she was pretty sure that if she went back into the dining room, she might find Jeff, wine glass high like a battle standard, already launched into the monologue about how we were in the era of weak bonding, the era of chastity and finger scolding. The only thing bad about this situation, between the kiss on the East River grass and the flirty little texts and the walk to the cherry blossoms, which would be strategically situated, probably, near some cheap hotel, was the harpy on the other end of the line trying to call everybody to account. An era of weak bonding, shrinking violets, wilting flowers, and on top of that, it seemed to be the era of tattletales, everybody always reporting each other, everybody keeping each other to their place.

“I mean, you think because you’re pretty you can get away with these things?” Julyne was saying. She sounded genuinely confused, like she were penning a letter to the Ethicist column of The New York Times. “You think it’s fun for you do that kind of thing – this is an old relationship, this is a relationship that’s supporting a lot, I mean why did you think it had anything to do with you?” The question was if Gabriel was in the same room, cowering off in a corner somewhere, head in hands, and that was the most likely, sad to say, teachers and parents liked the kid to be present when they had the truth-talk about them, when the kid was really being lambasted, it was part of the ethic, the pleasure, of the tattletale, the character report.

Eve studied the nudes on the wall, all the different ways they were turned. That seemed to be Jeff’s idea of interior decorating, for some of his nudes to be frontal, some facing away, some decorously seen along the flank. She was suddenly very tired. “I don’t know,” she said. “I look the way I look, I’m made the way I’m made, what am I supposed to do, pretend I’m just like everybody else?”

This was apparently the wrong thing to say, probably she’d been spending too much time reading about Nico, that was the kind of thing Nico would say, but not everybody could get away with the things that Nico got away with.

And she listened for a while to a detailed description of what a terrible person she was, how she had led on poor innocent Gabriel, how she had ruptured their beautiful relationship, how she had been a tease, everything she did a tease, and she tried to make a point of listening dispassionately and everything Julyne said did actually make a certain kind of sense, she could recognize herself in all of it, and it was too bad that the film would probably never be completed, that was unfortunate, a small stupid film but people had made it from lesser breaks than that, and there were so many plans, trips to the beach and movies to watch together and music to listen to together, that now would never materialize.

“You cannot get away with what you are doing,” Julyne said, and the timbre of her voice was something ancient, so archaic that all the words to describe it, shrill, hysterical, had been retired from the language. And she received her drubbing, she wasn’t a bad person really, if someone wanted to tell her off, she felt ethically bound to let them do it, and then Julyne finally ran out of gas and hung up sputtering and the food was probably getting cold and the wine losing its aeration or whatever and she opened up the window and let herself out with a small jump into Jeff’s garden patch and then onto Bedford Street and, look, that wasn’t completely necessary but she just couldn’t tolerate at this moment Jeff’s I-told-you-so cynicism, the way Jeff would tell her, probably correctly, that she just couldn’t be friends with these wet blankets, that she was a shark and the world was made to revolve around people like her, and him too incidentally, and yadda yadda, and, besides, you had to do these kinds of things every so often if you were going to build up a legend, you had to, for instance, climb out windows for no very good reason.

Walking down the street, Eve had the very rare, immense pleasure of having plans canceled and so having free hours stretching in front of her. Probably it was a mistake alienating Jeff, there was a great deal to be said for being allied to someone like him, letting him take care of things. On the other hand, it would be excruciating to watch, his philosophy, his music taste, his life advice, the way he would transition all of that from the dining room table to the bedroom. She was spared that at least, spared devoting this evening to Jeff’s orgasm face and all the orgasm faces to follow it. On her way to the West 4th St subway and the Murphy Bed and ‘Sunday Morning’ on YouTube, she passed by a news stand and bought a copy of Time Out Magazine, and it was a surprise in a way to find that any of those things existed anymore, just as it was a surprise to find herself rustling through her purse to find exact change and then looking through the listings and settling on an open mic night at one of the crappier places in the Village.

And it was exactly as much of a bust as she thought it would be. Everybody there was down-market from the math club hipsters playing their GarageBand arrangements. A pair of giggling teenagers just read their favorite section of Harry Potter. Another act seemed to be undisguisedly schizophrenic. When it was her turn, she got up and she read:

I praise the slum city

Slum Williamsburg slum Bed Stuy slum St Louis

Praise the laptops and murphy beds

Praise the also-rans and never-weres

Praise the casanovas of the coffee shop

Big talk patter on the way to day job

There was lots more where that came from, more poems, more maybe songs if she came across anyone who could set them to music, she read a very small sample – she didn’t want to tax her audience; they were on their cell phones, some of them were mentally ill, she wasn’t going to push things. Gabriel of course wasn’t going to read her poems and bring them to the publisher; if he did, he’d start World War III at home. And open mic night in this fossil of the Village wasn’t going to lead to anything, she knew that, but who gave a shit, something had to happen here, sooner or later someone had to start it up again.

I will give this a read at some point. Thanks.

Sam, could be better, could be worse. What's with all the photos? Trying to be W.G. Sebald? I do like that Eve is ever-so-slightly unhinged. I haven't seen a ton of that before. Character that's a bit nuts but not so much so that anybody else even needs to remark on it.