Dear Friends,

As some of you are aware, I’ve been in kind of a running battle the last couple of days arguing with people on Substack in response to Jonathan M. Katz’s Atlantic piece — which I take to be a hatchet job and written, actually, in bad faith — and I’ve been very surprised by the number of Substack users who agree with Katz and are adamant that the First Amendment has nothing to teach the private sphere about free speech. This piece is my attempt to zoom out a little from this debate and discuss some of the underlying issues.

Best,

Sam

FREE SPEECH IS ACTUALLY REALLY SIMPLE

The framers of the Constitution had a great deal to think about in devising a new country, but it’s always struck me as emblematic of something important that they chose to put free speech and freedom of the press right up top. (It’s even more significant than just where it’s placed in the Constitution — the anti-Federalists had made it clear that they wouldn’t take part in any Constitution without an accompanying Bill of Rights).

And, of everything else that’s questionable in American history, it’s that emphasis on freedom of speech, press, assembly and religion that we can be most justifiably proud of. The robust tradition of a free press —e.g. a pair of Washington Post metro reporters bringing down the president at the height of his power — would be unimaginable without that unambiguous constitutional protection. The civil rights movement — marches of the unarmed past stony-faced and violently-inclined law enforcement figures — would be similarly unthinkable without the inalienable right to assembly. In 1942, in North Africa, Ernie Pyle, no naif, was struck by the difference between the Americans and the Nazi-inflected French colonists he was encountering. “They couldn’t conceive of the fact that our strength lay in our freedom,” he wrote. In Central Asia, where I am at the moment, absolute freedom from bureaucratic or governmental interference seems an almost unattainable goal — it’s simply taken for granted that the press and civil society are subordinate to government; and the result (which everyone bemoans but no one can really do anything about) is oligarchic clusters that rule sometimes for generations.

I don’t think I’ve ever met an American who isn’t proud of the First Amendment, but there seems sometimes to be a failure to grasp that its strength is in how vanishingly simple it is. Government gives itself the goal of protecting “free speech” and prohibits itself from impeding free speech — and there is no attempt to caveat or qualify what that free speech might entail. The premise is that it is up to civil society (with an assist from the courts) to figure out exactly what free speech looks like.

That vision is rooted in a particularly 18th century optimism — the British tradition of parliamentary debate and dissent; the radical tolerance espoused by Voltaire (or pseudo-Voltaire) in the line “I disapprove of what you say but I will defend to the death your right to say it” and which was soon to be codified by John Stuart Mill as “negative liberty”; and in the specific revolutionary ferment of the early American republic (it wasn’t lost on any of the founders that Common Sense or, for that matter, the Declaration of Independence would have been impossible under a rigorous censorship regime). Basically, as Voltaire (or whoever it was) clearly understood, free speech only works if it’s rigorously maintained: allowing somebody else to express their view (however objectionable) frees you for the expression of your own controversial opinion. Chip away at others’ rights to speak or fully express themselves — however virtuous your grounds may be for doing so — and not only have you created some arbitrary arbiter controlling speech but that right is very likely to be unavailable to you at the time when you most need it.

I don’t think there was ever any illusion, in the Constitution’s framing, that the free speech principle wouldn’t run into some wrinkles. And, in the course of American history, there have been three main objections to it.

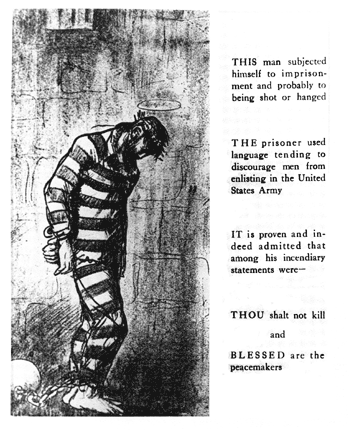

One is that unfiltered free speech allows room for “treasonous” content. That was always a concern of old-style, Red Scare-type conservatives and is the guiding principle in places like Central Asia or China where the press is expected to contribute to a harmonious, smoothly-running society. That objection is handsomely dealt with in the liberal tradition, where dissent is brought inside the political system in the form of “the loyal opposition” and where criticism is understood to be a salutary check to the inevitable consolidation of power.

The second objection is that radical tolerance would also protect and inclose the intolerant. This paradox really is very near the heart of liberalism, and there have been various figures in American history (Joseph Smith comes to mind) who somewhat playfully insisted on democratic protections for their communities while encouraging their communities to behave in wildly illiberal ways (with Smith, for instance, compelling his followers to engage in bloc voting for candidates selected by the Church). But, in the course of history, the paradox of tolerance has been less of an issue than it might appear to be. The US government interfered in “illiberal regimes” within US territory — launching an expedition against the Mormons in Utah; attacking the Branch Davidians at Waco — and those are remembered, rightly, as shameful events. Open societies, it turns out, simply have a power that closed societies do not, and, if left on their own, closed societies (even apparently radical sects like the early LDS) have a way of over time accommodating themselves to the liberal majority.

The third objection to free speech is that speech can be manipulated or coerced - that the playing field for free speech is never exactly equal. American history has, to a great extent, been about interests taking over communicative organs — whether that’s the 19th century publishing magnates (the Hearst media empire, etc), the television conglomerates that effectively governed American communication through the mid and late 20th century, or the web platforms. This gets into a very tangled place, as expressed in the tortuous body of law that wends its way through Citizens United. And that’s become the battleground for a particularly insidious critique of free speech, as it’s played out in the digital era. The argument there is that platforms like Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Substack only appear to be “public squares.” In reality, they are companies and have all the prerogatives of companies to set “policy” through “terms of service,” etc, that are carve-outs from First Amendment rights. What that means, also, is that the companies can be subject to immense outside pressure to “deplatform” those who express ideas deemed heinous. And in the general feeling that the “deplorables” are on the rise with the Trump election and with Covid “denialism,” the societal worthies have more and more leaned on this idea — that if a store can impose a “no shoes no service” policy, YouTube should also kick off purveyors of Covid “misinformation” and Twitter and Facebook should, if not outright ban, then, at the very least “deamplify” voices promoting discordant narratives, and Substack, as Jonathan Katz’s recent Atlantic piece would have it, should distance itself from the “Nazis,” who, Katz cherry-pickingly claims, “have made a home on the platform.’

There is a reasonable argument to make that the private channels used for mass communication create inherent imbalances — that government is needed to step in to break up various conglomerates (as Chris Hughes urged for Facebook a few years ago, as various lawmakers argued for TikTok last year before everyone forgot about it). What — to put it simply — drives me crazy, though, is when citizens ask for the platforms themselves to screen out undesirable elements or content, on the grounds that the speech itself is basically “owned” by the company, the same way that a “no shoes no service” policy would be. This argument is particularly insidious at a moment when “the public square” as such doesn’t really exist — when virtually all meaningful public discourse is conveyed over the distribution networks of “private” companies.

The long body of Supreme Court jurisprudence has ruled to, as much as possible, stick to the hands-off approach of the First Amendment and to limit any of these apparently well-meaning incursions into free speech. That’s in Brandenburg v. Ohio’s ruling that speech be restricted only if “inciting or producing imminent lawless action.” That’s in the ringing lines of West Virginia v. Barnette that “if there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics…or other matters of opinion.” But, strangely, a surprising number of people — and this view is at the moment clustering on the left — are looking to be far more censorious than the judges have been. They don’t want to be “next to Nazis” on the Substack platform, they call — as The Verge’s Nilay Patel did in an interview with Substack CEO Chris Best — for a far more robust content moderation policy that would, for instance, ban “overt racism.” In that interview, Best’s dignified response that Substack has “a strong commitment to freedom of speech, freedom of the press….and we think that it would be a failure for us to build a new kind of network that can’t support those ideals” was met by Patel’s assertion that “you know this is a very bad response to this question, right?” and with a zeroing-on in how Substack would handle a hypothetical example of hate speech.

Anybody who makes these arguments for companies to exercise their muscle and to have “community guidelines” for speech going beyond the First Amendment immediately starts fantasizing about some society of guardians, or content moderators, who are able judiciously to chop off the extremes and to ensure that the discussion is sane and reasonable.

But in my lifetime I’ve encountered two instances of this sort of embedded moderation of discourse — both times with obviously deleterious results. One was the long-standing adoption by television of FCC “indecency and obscenity” regulations and the other was widespread moderation on social media. In the case of television, the FCC guidelines were perfectly well-meaning and civic-minded. And the result? The almost completely inanity of American television for a half-century — a steady diet of treacle which ultimately undermined television as a whole. As soon as HBO arrived, with its cursing as well as sex and violence, viewers found themselves willing to pay for premium services at the expense of the FCC-governed networks, and an entire industry emerged of cutting-edge, high-quality shows that had cursing as well as sex and were much closer to the complex realities of adult life (“the golden age of television”), while the networks, which had once had about as secure a monopoly as anybody could possibly hope for, faded, largely through their self-imposed censorship policies, into well-deserved oblivion.

The story of the digital platforms is by now well-known. In the ‘90s and ‘00s, the internet meant freedom, non-regulation, a wild space full of trolls and weirdos but also of startling, interesting content. Towards the mid-2010s, the consolidated social media giants, many of them under concerted pressure from the liberal press, became highly concerned that they had abetted Trump and were encouraging the fringe, so they overreacted. They put out byzantine terms of service, engaged in complicated and underhanded practices of deamplifying and burying politically unsuitable content while lying to Congress’ face that they’ve were doing so, hired legions of content moderators who were very different from the noble guardians that the community guidelines crowd had in mind — they were low-paid workers on off-shore sites, frequently speaking English as a second-language, working in what seem to be hellish conditions, asked to weigh in on for instance complicated medical assessments and often getting it wrong — or, increasingly, they were AI bots.

On a purely legalistic basis, I can understand the argument that private spheres can impose their own codes of conduct that supersede the First Amendment. I can understand wanting schools to impose rules (no cursing, no bullying, dress code, whatever it is) that produce a safer environment — although even that isn’t my style (and the Supreme Court has limited what schools can impose). But why any adult would want to trade a free field of discourse for a discourse controlled by the nervous whims of Mark Zuckerberg or by Mark Zuckerberg’s lawyers or by an AI bot is beyond me.

The truth is that the First Amendment (together with the jurisprudence that’s developed around it) offers as effective a guidance to modes of discourse as anything that anybody is likely to come up with. It was a bold experiment in its time and it’s worked out better than anything else I can think of in American history (thanks as well to Madison’s insight that, in free discourse, the extremes would tend to cancel each other and actually help to ballast the society). Private institutions are free to come up with their own modes for regulating speech, but then, once they do, they need content moderators, enforcement mechanisms, etc, and before they know it they’re in the morass that Twitter got into. Sometimes, freedom is just cheaper and more efficient as well as simpler.

If free speech has little to teach private parties then who is the government actor in the seminal First Amendment case NYTimes v. Sullivan?

More broadly, I found the Atlantic article a little naive. Substack doesn’t have a Nazi problem. Our society has a Nazi problem. Substack is doing great given the society it’s stuck in.

I’m just starting to read this. I wanted to jump in and say that as far as I’ve seen you are the only substack writer speaking up for free speech. At length, at least. @popehat (ken white) is in a different category as he regularly writes and podcasts about it.

I appreciate your taking this stand. It’s surprising to me that free speech doesn’t seem to have too many defenders on here; maybe I shouldn’t be surprised as it never seems to. But these days it’s even more in retreat than usual.