Look. I need to start this with caveats. Writing is a vast city and there are many roads into it. Some of what I’ve disparaged below will work well for some people. And I’m hardly in a position of feeling like I have the answers and can criticize what anyone else is doing. Where this piece comes from, however, is being mindful of the ways I’ve been stalled and stuck in my own writing life — which didn’t so much have to do with instruction (I never took that many writing classes) but with some pat ideas about writing that were circulating freely around the culture and embedded themselves in my mind — and knowing the difference in my air quality and the quality of my life when I’ve been able to write freely and confidently, which largely is a matter of forgetting what I’ve been told.

These are a few of the truisms that I would subject to real scrutiny:

-Writing Is Rewriting. The overriding kind of ur-belief in contemporary writing world is that successful writing is the product of endless editing. I’ve seen people be wildly creative in how they rip apart their first drafts. The premise is that a first draft is a kind of festering turd on a page, that you’re just supposed to get it out of your system and then once you’ve done that the real work can begin. As Anne Lamott writes in ‘Shitty First Drafts,’ “The first draft is the child’s draft where you let it all pour out and then let it romp all over the page….No one is going to see it…But there may be something in the very last paragraph on page six that you just love, that is so beautiful or wild that you now know what direction you’re supposed to be writing about.” It’s always been perplexing to me what writers think is going to happen to them between this first abominable draft and the fifth or sixth draft, but Lamott supplies the key metaphor: you’re supposed to grow up in that time. The expectation seems to be of a dramatic transformation in yourself from the time you wrote your story to the time, several days or weeks later, when you sit down, sadder but wiser, with a red pen in your hand and begin drawing arrows all over the place. What it means in practice is second-guessing, worrying your story to death. I have to admit that I’ve never really gone through an edit process in my work — my brain freezes up at the thought of it, it always feels to me like trying to edit a conversation or a dream — but I’ve seen it in film and journalism. There, it is necessary and does make a certain amount of sense. You tend to have so much raw material that you have no choice except to try to sift it down, but that necessary editing is only a very small part of the process. The bulk of the editing there is ‘notes,’ which is a form of politics. It’s taking the raw material of what your story has given you and trying to shoehorn it into the pre-determined slant of the publication or pre-determined formula of the film’s channel of distribution. In film or journalism, you sort of have to endure it, because it’s the only way you’ll get paid, but it’s very strange that the same set of principles should be facilely applied to creative writing, which isn’t (in theory) supposed to be a political activity, which is about expressing your truest, purest self. It seems to work for some people — there seems to be some Michelangelo process of finding the true form of the sculpture somewhere in the endless chipping away at the rock — but what it mostly is is importing the censor and worrywort from the editorial meeting into your psyche and giving them all the power at the expense of your free, creative self. I can always tell when writing is over-crafted, when it is worried to death, in retreat from itself — and everything I read in the literary fiction market is over-crafted. Writing is the chance to really be you, to say what you think and feel in the most genuine, most spontaneous way. Why would you ever turn that power over to another, more craven, more everyday part of your psyche?

-How well you write is largely a matter of how receptive to feedback you are. I’ve done one workshop in my life. I enjoyed the experience. People actually do read your piece — certainly in a far higher percentage than if you’re e-mailing your story to your beleaguered friends. Even allowing for politeness and evasion, by the end of the discussion you have a good idea of whether your story worked or not. But I almost can’t imagine how the chorus of notes that the room gives you could make your story better. What everybody is telling you is how they would write it if it were their story, and they are, ipso facto, a different writer than you are. If the inner censor is not particularly helpful, the outer ones won’t be either. What they represent, again, is a kind of political process — letting you know where the cultural mainstream is, guiding you towards market, wrenching the story away from how you and your daemon really want it to be.

-Writing is a team activity. Acknowledgments sections of novels have been metastasizing and they are, very often, the most sincere and genuine expression in the books that I read. They come across like a politician effusively thanking their supporters in their victory speech — which is exactly what they are. They represent a process of being affirmed and a process of being shepherded through an industry. What they are not, however, is what they claim to be — those being cited in an acknowledgments section are not like the guys in the pit of a NASCAR race fixing up a bolt here and there. A novel is a very different entity from an overheating race car. It is the expression of your strangest, least socially-bound self. I can’t really imagine who these gladhanding, student body president-type writers are who are soliciting opinions on their book from every one of their friends and relations — and then, if the acknowledgments are to be believed, acting on them.

-Write what you know. This is true and good advice, but it has real limits. Literary writing in our era has, under the diktat of this maxim, largely become a a process of killing your own imagination — of writing memoir, which has been elevated into an art, or of writing ‘autofiction,’ which is basically memoir with a few of the names changed. The publishing industry, responsive to what’s happening, tends accordingly not to reward or even look for imaginative writing. It looks for memoirs of people who have had the most interesting lives — which tends to mean, ipso facto, just about anyone who is not a writer. And there is a creative dead end in here as well. There is a point, actually, where you run out of stuff, or where you get tired of your own identity, or where other consciousnesses seem more interesting to you than your own, and that’s where — as other literary eras recognized — the real work of writing begins. Imagination is a muscle like anything else, but it’s hard to develop if the culture (and the writing workshop world, in particular) doesn’t encourage or even believe in it.

-Show don’t tell. This is also good advice, but it’s the first and last ‘rule’ that most writers take in, and the result is, everywhere in literary writing, a kind of frenetic, slapdash watercolor effect — writers determined to create these poignant little allusive scenes that surpass direct understanding. It has its place and helped to correct for the polemic of an earlier era, but it sort of forgets what writing is essentially. Writing is like a condemned man having his one choice to speak before a court, it’s a matter of saying who you are and what you believe in before a mostly-indifferent outside world. Usually, if I’m reading something, the main question I have is what is the writer saying. If they’re saying something that’s genuine and emotionally honest, I tend to think it’s good writing, even if it’s not particularly well-crafted or whatever. If it’s a set of incomprehensible allusions or eddies of elegant prose, I tend to think that it’s bad — and, let’s face it, that’s what most ‘literary writing’ is.

So, what do writers have to learn? As they’re developing, writers have to learn the following:

-Voice. Modern American writing teachers tend to be very good, in my opinion, at emphasizing the importance of voice. But there’s a paradox in here (as many of them understand). Voice can only come distinctly from you, not from a teacher or class. Anything that’s instilled in you, from however impressive an institution, however brilliant a writing guru, is, by definition, not your voice. Some people get lucky and seem to have a ‘voice’ from birth. Some people get it once and then never again (this seems to have been what happened to Joshua Ferris, for instance). But, for most people, the process of obtaining a voice is to sort of drop out of society for a bit, to have all the clamoring voices from their various social roles quiet down, to lose track of their different influences, and then, as Bukowski put it, your real voice “comes out of your soul like a rocket” … or doesn’t. But there’s no way to find out if you don’t go through that quietening-down, that internal exile.

-Confidence. This is the most important thing in writing and the hardest to get from any sort of institution or class. Workshops seem to be built around a logic of humility — at the moment of truth, you are supposed to shut up and take the feedback. Even for people who excel in institutional settings, there’s always a premise that there’s some other institution out there that’s more exacting, more impressive, where you will have to begin all over again. And, in any case, the inherent structure of institutions — some teacher set up in a figure of untouchable authority over you — is designed to inhibit the development of your own confidence. Real confidence has to come from somewhere else — and, usually, develops much later in life. That confidence tends to come, I believe, from a sort of process of elimination. At some point, after you’ve had your formative experiences, had your various inputs, your humbling moments, etc, you realize eventually that no one else has anything you don’t have — no one has any intrinsic authority, or even particularly any wisdom, no one has the right to speak any more than you do; and, with a kind of shrug, you learn to trust yourself and your own particular voice no matter where it may lead. That is very different from hubris or vainglory — very different from believing that you are somehow better than anyone else. It has its own humility. To speak in sort of pagan language, you create a container that is robust enough and sure enough of itself that your daemon, who lives somewhere deep in you, learns to trust you and, little by little, is willing to share with you its secrets.

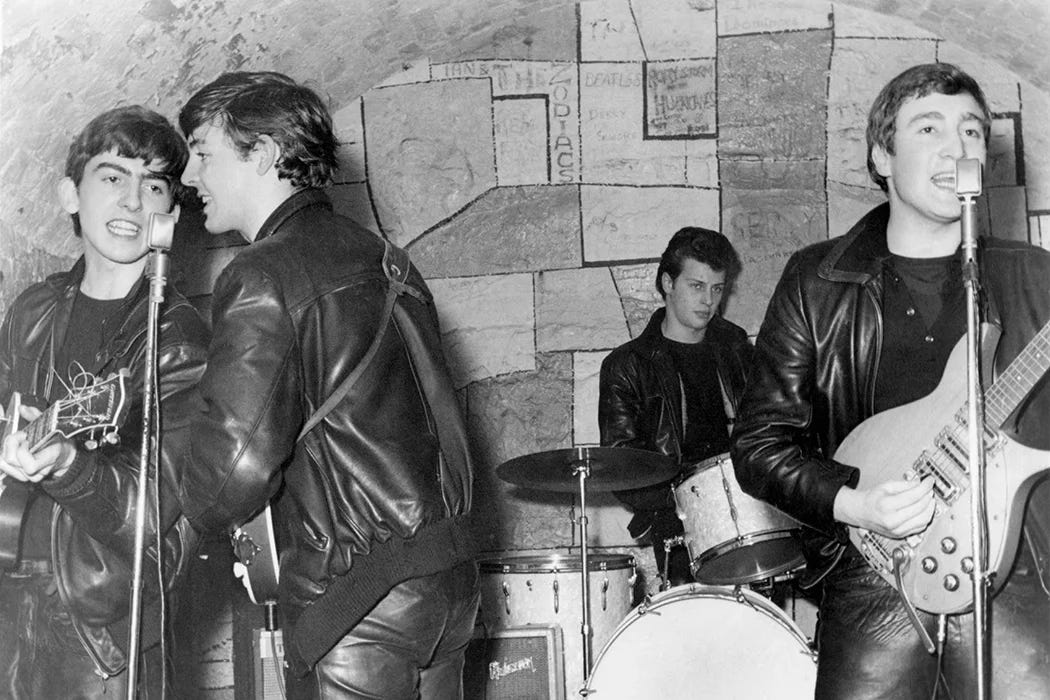

-Volume. Probably the two most effective pieces of advice I received were from the college class ‘Daily Themes’ and, god help me, from Malcolm Gladwell. I was so embedded in the idea that writing required endless craft and reworking that I took Daily Themes thinking that its premise — of writing a fresh piece every day — wasn’t really possible, that it was the same sort of freakish circus trick as, like a 24-hour play. But it is possible to write a fresh piece every day, just as it is possible to write (and produce!) a play in 24 hours. It’s mostly a matter of stretching oneself, and committing to volume rather than what is often the first instinct for writers, which is to hoard and to try to write the greatest thing ever. Gladwell somewhat clarified that idea for me when I read Outliers in my mid-20s. The striking case was about the Beatles, how the Beatles came to be the Beatles. And it was, claimed Gladwell, from an episode I hadn’t known about in 1960 where a somewhat tyrannical promoter compelled them to play for eight hours a day, seven days a week, in Hamburg. “The Hamburg crucible is what set them apart,” Gladwell writes. There really was one thing that all the wonderful, impressive, successful writers I knew had in common — and that was that they wrote. They just sat down and they did it over and over again, and didn’t worry too much about overshooting the runway. Gladwell was annoying in all sorts of ways, but he was right about this. The work was not in the excelling or the perfecting but in the doing.

-Physicality. The other really valuable piece of advice that I got was also from Daily Themes and its sainted professor, Bill Deresiewicz. “Writing is a physical activity,” he said, and it took me a long time to understand what he meant but eventually I did. Often, with writing, I think about a story I heard (whether the story is true or not) of an ultra-marathon runner who is completely lacking in the sense of pain. He has a coach who rides alongside him and tells him, basically, when he’s about to die and needs to drink water or something. That’s I think more or less what the relationship should be between you and your daemon. The daemon, if probably encouraged and nourished, can run forever. Your job, really, is just to take care of it, to make sure it remembers to pay its rent and call its parents, that it has the coffee it needs and doesn’t get drunk too often, that its moods (which can be very capricious, much more so than a normal person in normal social engagement) are looked after, and above all that it has the time and space to do what it enjoys.

-Building a machine. What makes writers most different from other people is, I believe, that they tend to construct a writing machine in their minds. This machine can start to be developed in childhood, maybe long before they’ve ever thought of writing anything. It’s different for everybody, but it’s a way of observing, of detaching slightly, of storing impressions away, of perceiving rather than judging or participating. Usually, when a writer starts keeping a notebook is when their machine reaches industrial scale. That machine can be difficult for them, for the management of their own lives, for the people around them — it can be equally important for writers to find ways to turn the machine off every so often, to take breaks from it — but I find it hard to imagine how a person can have writing as a consistent part of their lives without having that machine baked into their temperament.

How you can teach any of those things is beyond me, and the answer, probably, is that you can’t. But I’ve always felt that the kinds of people who give advice to writers are in far more need of advice than writers themselves. Basically, there’s only one thing that can be said to writers. It’s not elements of storytelling, it’s not ‘show don’t tell,’ it’s not ‘constructive criticism.’ It’s just endless encouragement — and compassion. It’s, in the end, a completely solitary activity — and has to be. It’s about reaching the most extreme corners of yourself. Other people — teachers, friends, even, in the end, readers — have no place really in it.

Thank you for such an insightful article on the skill and the vocation of writing. I come from the land of teaching grammar and comma splices, and I know that good writing doesn't suffer fools who mindlessly follow rules. Two notes: First, inspiration sometimes trumps editing. Shirley Jackson wrote "The Lottery" while walking her baby. The short story is a first draft. Sometimes leaving work alone is best. Second, popularity of the memoir has arisen in relation to the selfie. Everyone seems to want to turn eyes toward self. True writers see the world differently, as you note. A writer listens, observes, reflects. A writer-- as Silas House remarks-- may never write a word and still be "a writer "

Good ideas throughout. Thank you!