Dear Friends,

Happy holidays. I’m sharing an ‘experience’ piece - a meditation on Buffy The Vampire Slayer, Mad Men, Man on the Moon, and the ‘social credit system’ that we’ve developed through social media.

Best wishes,

Sam

ETERNAL HIGH SCHOOL

The great lie over a half-century of American cultural life was of the high school hero - the idea that you could do something or other (in movie versions, something with a moral character) that would make you beloved to everybody in your school, which was understood to be your entire community, and which would define the rest of your life. There were two ways that that myth was punctured. One was the Friday Night Lights/‘The River’ variant - which pointed out that, for the high school heroes (and they did exist but were almost always jocks or pretty girls), the rest of their lives would be a terminal, irreversible decline. The even more trenchant variant was the ‘high school dystopia,’ an understanding that, for anybody other than the popular steadies, the king and queen of the prom, high school meant a weird warehousing of adolescence, a rigidly structured hierarchy, based of all things on varsity sports and cheerleading, and the only path to any sort of personal fulfillment was to keep your head down and to get as far away from it as possible as fast as possible.

As is - by now, I think - widely understood, the WB’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer really was the American work of art of the late 1990s. Buffy was based on a fairly simple idea - that high school really was hell, and that the only salvation from high school was inner life, a rich, alternative way of being that might be incomprehensible to anybody within the hierarchical high school structure but was the only means to staying sane. (The really classic scenes in Buffy tend to be about the skeptical school principal coming across Buffy and her friends just after they have dispensed with a demon, with no trace left of it, and with no ability to explain themselves to him.) Buffy was designed, really, to end soon after high school graduation with the idea being that the show’s premise no longer really had a point. Once Buffy went to college, and then left Sunnydale and became an independent person, she would be free of the demons; and, as the show stretched on (network pressures keeping it going longer than it should have), the ruses to keep her within the high schoolish power structure seemed more and more contrived.

But that was then. Social media - Facebook and MySpace most conspicuously - started really as a means of replicating in virtual space the hierarchical structure of high schools and colleges (instead of money, popularity as the currency) - and from there spread to take over the rest of the adult world. In his permanently delayed adolescence, Zuckerberg has made this idea explicit. “You have one identity,” he said in 2010. “The days of you having a different image for your work friends or co-workers and for the other people you know are probably coming to an end pretty quickly….Having two identities for yourself is an example of a lack of integrity.” For the other architects of the Web 2.0, as for Zuckerberg, it’s the internet’s inherent tendency to disperse identity that’s been the real bugbear. And the energy of the corporatized web has been all about consolidating identity - digital signature, two-step verification, verified accounts, etc (with doxxing as the preferred tactic of the pitchfork-wielding public in league with the new regime).

Taken together, the energy of the web (and, with it, our entire era) amounts, basically, to sending Buffy back to Sunnydale, insisting that, even distinct from the metric of income, there is a permanent metric of social credit, of status, as determined by reputation and, most crisply, by popularity. Intelligent commentators have been talking about it as the rise of ‘casino capitalism’ or the ‘gamefication of society’ - in Justin E. H. Smith’s phrase. What they’re thinking about above all are the ‘tokens’ of virtual popularity - the way that those tokens can’t necessarily be traded for actual wealth but lock web users, and society as a whole, into a cycle of constant addiction and constantly delayed gratification. On a cultural level, another way to think about it is being in permanent high school hell - never graduating, never developing an independent existence as an adult (with, in fact, one’s high school or college classmates usually able to track every last thought one has).

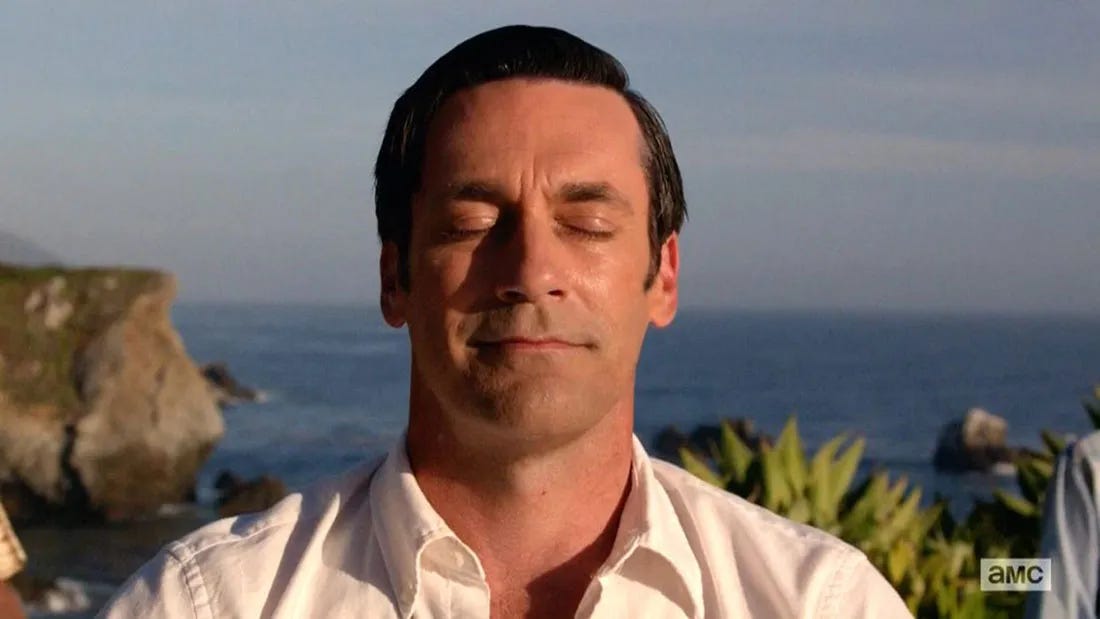

If Buffy the Vampire Slayer was the American work of art of the late ’90s and early ’00s, then, by universal acclaim, I would say, so was Mad Men for the late 2000s and early 2010s, the period of social media and the Web 2.0. And, in the way of great works of art, Mad Men seemed to hoover up much of the mood of that time. In theory, the sorts of closed, jobs-for-life corporate environments that Mad Men depicts were history, but Mad Men seemed to be intuiting that that was the underlying reality of our era. Mad Men is all about small changes in reputation - Peggy moving up, Don occasionally plateauing, Ginsberg moving up, Duck moving down, etc - and accompanied by a constant terror of doxxing (personal secrets, Don’s above all) that, if revealed to the wrong person, would be the end of a career. The office - and the environment of Madison Avenue in general - turns out to be a very small echo chamber. Ostensibly, all sorts of seismic, revolutionary events are happening in the culture-at-large. In reality, everybody shows up to work every day and the permanent struggle to guard and enhance one’s reputation never, ever loses its grip.

Mad Men hints constantly at a way out - some sort of an open road or radical rupture that the primary characters themselves are almost never willing to take but that does have the potential to let some air and light into their suffocated world. And Man on the Moon, Miloš Forman’s film on Andy Kaufman, picks up, I think, right where Mad Men left off. In an interview on his performance, Jim Carrey talks about the moment when he committed to inhabiting Tony Clifton, which was like falling out of a plane and knowing there was no way back. It was one thing to be Andy Kaufman - Kaufman, for most of the movie, is a well-liked funnyman - it was something else entirely to be Kaufman’s altar ego Tony Clifton, to be the boor, the person everybody hates, ‘the high school loser.’ For Carrey, it was a moment of absolute terror and real truth, and in a sense he never came back from it. “When the movie was over I couldn’t remember who I was anymore,” he said. “So you step through the door not knowing what’s on the other side. And what’s on the other side is everything.” His persona now, his whole existence, seems to have nothing at all to do with the funnyman in Ace Ventura or Liar Liar, and he seems, to just about everybody’s consternation, to have moved on to some kind of higher plane, not really caring what anyone thinks of him.

Listen to Carrey’s interviews and it’s basically all about duplication, having altar egos, personae, knowing that if everybody hates Tony Clifton, well, he’s not really Tony Clifton; and so, by a similar token, if everybody hates Jim Carrey, well, Jim Carrey is just another persona - and that has freed Carrey in ways that seem to be unheard for anybody in the celebrity-matrix, anybody in the era of the digital signature and the lifelong social credit system. From the beginning, the subconscious of the internet has been about trolldom - about anonymity, ‘handles,’ ‘avatars,’ etc. With the Web 2.0, that era seems gradually to be coming to an end - for one thing, everybody is sick of the trolls; and, more importantly than that, they are a threat to the corporate consolidation of virtual space - but there is something that is worth listening to in the internet’s subconscious, just as the characters in Mad Men seem always just on the cusp of hearing some sort of tune that would take them into a completely different way of being. That path has to do with resisting ‘digital signatures,’ with inhabiting different personae, and, through that, seeing the self as a constantly shifting, constantly transforming persona that is (whatever social media might try to tell us) in no way fixed.

Can we be in the machine and not of the machine? Yes, but it's hard.

I like your piece, how you explore identity and being a person in a world that has popularity/social status as measure of self. I like how you reference cultural shows and what they teach us. I have resisted having a social media presence myself for years. Refusing Facebook and only going on Instagram a year ago for these very reasons - not wanting to compete in a popularity contest nor having to have a set identity when I see myself as an evolving being. Thanks for the thoughts tonight.