Dear Friends,

I have a piece up for

on the Ta-Nehisi Coates/Tony Dokoupil fracas.Best,

Sam

ETERNAL 1948

If you ever find yourself talking to me, it’s helpful to know that sometimes I’m more or less living in the past. Recently, for some reason, I’ve been mentally living in the period around 1948 — and I’ve been doing so very happily. It seems to me that, in broad outline, we’re almost uncannily facing the same set of geopolitical challenges.

The parallels of course aren’t perfect. We’re not in the aftermath of World War II now and there was no parallel to Trump in 1948, but what was basically happening was a sense of waking up from a holiday from history (a two-year respite in the case of 1948, a thirty-year vacation for us) and dealing with some astonishingly vexing problems.

The first, vast challenge of the architects of US foreign policy in the late ‘40s was the recognition of the entrenched hostility of the Soviet Union — that the United Nations and the goodwill at the end of World War II notwithstanding, there simply wouldn’t be anything like a liberal-minded Concert of Nations administering the peace together. For those who were part of the foreign policy apparatus of the time, there was something unforgettably exciting about it. “We were present at the creation,” said Dean Acheson, the Secretary of State. “You don’t sit down and take time to think through and debate ad nauseam all the points,” aide George Elsey said. "Later somebody can sit around for days and weeks and figure out how things might have been done differently. That is all very well and very interesting and quite irrelevant.” That was the era of the Truman Doctrine, the Marshall Plan, the containment strategy. Maybe more indelibly than that, it produced NATO and the CIA.

With national borders only lightly redrawn from that day to this (the key change are the emergence of the CIS countries out of the Soviet Union), we are to a surprising extent still circling around those decisions. The really key issue in the 2024 election is Trump’s promise — if he’s at all serious about it — to withdraw from NATO if elected. Meanwhile, we seem to be headed for a new kind of Red Scare, with the discovery that Russia and China are intent on disinformation, espionage, and election interference in the US (just as the USSR really did have a robust espionage network set up in the West by the late ‘40s) but without any real sense of how dangerous those penetration activities actually are or whether the cure would be worse than the sickness in attempting to counteract them.

What’s worth noting about the geopolitical decisions taken by the 1940s foreign policy architects was that they weren’t particularly focused on Communism as an ideology. What mattered to them was Russian imperialism — the belief (which did seem to be confirmed both in the Berlin Blockade and the invasion of South Korea) that Stalin was interested in expansion. That’s fundamentally the question that US policymakers have to grapple with now — whether Putin will be more or less satisfied with whatever gains he makes in Ukraine and China is content with the status quo; or whether the Ukraine invasion is a prelude to contained revanchism and China is just waiting for the opportunity to gobble up Taiwan.

These calculations were difficult in 1948 and they’re difficult now. Basically, the US policymakers got it wrong from multiple directions then. They somehow failed to realize that Korea was the imminent flash point while also adopting, in NSC-68, an overzealous argument that the USSR was bent on world domination.

I’m not exactly sure, actually, what US foreign policy is at the moment. The US’ aid to Ukraine seems like a direct extension of containment, but it’s very far from clear whether the US foreign policy establishment has any grand strategy when it comes to Russia and China. As far as I can tell, it seems to just be a continuation of 1948 — drawing the line in the sand at the 38th parallel and in the Strait of Formosa and, now, somewhere in Donbas as opposed to Berlin.

Even more challenging for the US in 1948 was Israel/Palestine, and, as Harry Truman’s daughter Margaret recalled, “this was the most difficult dilemma of all.” What’s striking is how little has changed — even down to the factional divisions within the US government, with the office of the presidency tending to be more pro-Israel and the State Department feeling that defense of Israel was a geopolitical dead end.

In the case of 1948, that resulted in a high-stakes personal showdown between Truman and George Marshall, then the Secretary of State. Marshall, “the great one of the age,” was far more popular than Truman and absolutely critical to the administration’s survival in an election year — and Marshall had come to be adamantly opposed to the U.S.’ recognition of Israel. “We are playing with fire while having nothing to put it out with,” Marshall said.

Marshall had already gone around Truman’s back by proposing a UN trusteeship as opposed to the White House’s favored partition plan, and, in a testy meeting in the Oval Office, Marshall declared that if Truman went ahead with unilateral recognition for Israel, Marshall wouldn’t vote for him in November. “There was this awful, total silence,” Clark Clifford, who was at the meeting, recalled. “That was rough as a cob,” Truman, who had a homespun way of speaking, said as soon as Marshall had left.

But, in the end, it was Marshall who backed down rather than Truman. Truman was sympathetic to the plight of Jews and to Israel, and was highly aware of the importance of the Jewish vote in the election, but had been worn down by the intemperance of over-impassioned Zionists. “Jesus Christ himself couldn’t please [Jews] when he was on earth so how could anyone expect that I would have any luck,” Truman said, which is — one has to admit — a pretty funny line. Nonetheless, Truman held his ground, and when Marshall called to say that he would not oppose Truman publicly, Truman turned to Clifford and said, “That is all we need.”

The White House rushed through the recognition, and, when word of it reached the US delegation to the UN, they were “flabbergasted,” David McCullough writes. “Some American delegates actually broke into laughter, thinking the announcement must be somebody’s idea of a joke,” he continues.

I’m dwelling on the details of this to emphasize what a close-run thing the recognition of Israel was from an American perspective. The fear that Truman and Marshall both had was that the United States would essentially be asked to provide security for Israel and wouldn’t necessarily be able to do so — and certainly not without alienating the entire Arab world. Very little of that fundamental calculation has changed. The current behavior of the State Department is to keep somehow wishing the problem away — fantasizing about Middle Eastern ‘grand bargains’ or some kind of a ‘confederation’ between Israel and Palestine but without quite coming to terms with the fact that, as George Kennan put it, the conflict between Israel and Palestine was an insoluble problem. A Jewish state had to exist — there was no other solution to the post-Holocaust refugee crisis — and the Arab world was, then as now, absolutely unwilling to accept it. The lesson of 1948 is that nobody else, really, had any bright ideas. The conflict was intractable from the start.

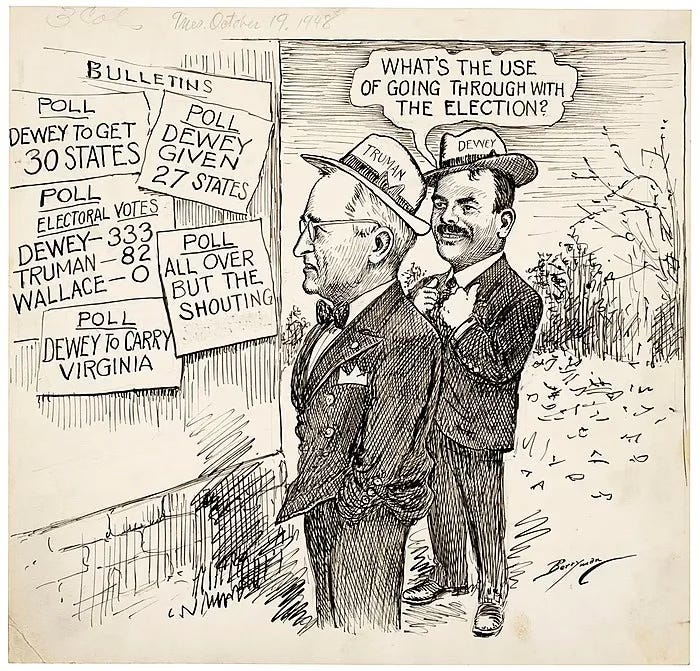

In the middle of having to manage the Berlin Blockade, the recognition of Israel (and subsequent war), and the ongoing establishment of the national security state, Truman also had an election to deal with — which, for most of 1948, looked as if it would be a Republican landslide. I already wrote about the election earlier this year, as an encouragement for Biden to lose about twenty years and get out on the stump, and now I’m saying the same thing re Harris. A number of election fundamentals seemed to be pointing the Republicans’ way. Truman wasn’t very popular. The country was clearly tired of the Democrats and wanted a change. Betting agencies had odds of 15:1 against Truman, every single poll conducted during the campaign predicted his loss, and, in a poll of campaign correspondents (i.e. the people best situated to know what was going on), fifty out of fifty called the race for Dewey. Not only that, the Dems, after 16 years in power, had somehow run out of money. The Truman campaign couldn’t pay for radio ads — then the dominant form of mass media — and barely enough to support Truman’s whistlestop campaign. “We were one jump ahead of the sheriff,” his press secretary recalled.

But that didn’t stop Truman. During the campaign, he traveled 20,000 miles, delivered 350 speeches, spoke in person to over three million people. “He used no jargon, no stock jokes, nothing cute,” writes McCullough. “But the intent of his thought was always clear.”

It wasn’t actually that there was anything wrong with the polling methodology. “I couldn’t have been more wrong. Why I don’t know,” a chagrined Elmo Roper said afterwards — but, really, he needn’t have been so hard on himself. The polls reflected real sentiment. It was just that Truman worked so hard — while Dewey tried to coast into the White House — that he changed the underlying dynamics of the race. Dewey talked in airy platitudes — “our streams are full of fish” — while Truman endlessly attacked Republican cupidity and the Republican “do-nothing Congress.” Truman reached more people, and, eventually, voters remembered that they liked him personally and were generally happy with Democratic policy. “What’s the matter with that fellow anyway? Can’t he stand four years of prosperity?” one farmer joked of a Dewey-voting farmer. In the end, the race came down to something that nobody could have controlled or predicted or would have even thought about — the price of corn dropped and that swung enough voters in the farm states that were expected to be safely Republican. “The farm vote switched in the last ten days and you can analyze figures from now to kingdom come and all they will show is that we lost the farm vote,” Dewey wrote afterwards.

But, of course, one man’s lucky break is another man’s shooter’s roll. Truman was in position to capitalize on the change-of-heart among the farmers because he had outworked and outhustled Dewey even in the states that were supposed to be safely Republican. The message is obvious — so obvious that it seems ridiculous to say it. Harris should be out speaking to every podcast and television channel and vlogger that she can think of. It shouldn’t just be 60 Minutes and Oprah and Alex Cooper. It should be Joe Rogan and Theo Von and all the kinds of people you would be expect to be Trump-leaning. Joe Biden’s excuse for not doing this kind of thing was that he was decrepit. I’m not sure what Harris’ excuse is.

The point is that, in politics, nothing ever really changes. Geopolitically, we’re in a very similar set of dilemmas to 1948. The Middle East is as intractable as it was then — and, likely, ever was. And the rules of electoral politics are, if anything, more unchangeable than that. It’s just a matter of give-‘em-hell-Harris. The more people you speak to, the more people who are likely to vote for you. There are no spreadsheets worth analyzing. There's no smart analysis at all, really. It’s just about finding the largest possible audiences and hitting them with a simple, consistent narrative.

1948 is not only the year Israel became a reality but the year thousands of Palestinians were permanently displaced to create that reality. It was violent,bloody and heartbreaking without practical or wise consideration of how it might be done differently. It wouldn’t have been anywhere near perfect but it could have been based on recognition of the humanity and shared history of Arabs and Jews whose ancestors occupied that land for hundreds of years. Without that basic consideration, we witness the devastation and heartbreak of today. This isn’t just politics being politics, it is the ugly part of human nature which continues to diminish the humanity of anyone who is perceived as “other.”

In a similar to 1948 arrival the Declaration of human rights I am not done reading was so far the most spot on one could expect from tempered in hells committee of hominoids. Some iof the medicalized demands of heady talkers 2011 etcetera fall and creakily drop away like plant matter. I hope it all is as giod as it starts People have the right to seek legal redress because: that is what people do and have done. Watch the Paul Scofield King Lear. On y-tube it is How you see you have got it: it says it is Scofield Lear trailer but it is 1: hour 57 minutes. ALSO check Greg Palants's prediction certified into a free movie that fraud complsints this election will reck chaotic. JKh / Hawkins interviews Palanst on Counterpunch Articles. Sounds vomitos...