Dear Friends,

I’m sharing a piece cross-posted at Inner Life.

Best,

Sam

DOES THE PAST EXIST?

Here’s one of these internet arguments that make barely any sense in the actual world.

In Michael Lewis’ Going Infinite, he quotes that eminent literary scholar Sam Bankman-Fried as saying:

I could go on and on about the failings of Shakespeare, but really I shouldn't need to: the Bayesian priors are pretty damning. When Shakespeare wrote almost all of Europeans were busy farming. By contrast there are now upwards of a billion literate people in the Western sphere. What are the odds that the greatest writer would have been born in 1564? The Bayesian priors aren't very favorable.

This was widely read for the comedy value it offered, but, in October, Substack’s most-hard-to-place (if not most controversial) writer Richard Hanania weighed in, unexpectedly taking Bankman-Fried’s side:

This is obviously true, and a litmus test for rationalism. Only in subjective fields like literature do we see the "best" people having lived long ago.

Hanania gamely tried to defend himself even as he was being raked over the internet coals, but there was something about this set of arguments that bothered me (as it did many people) far more deeply than would be the case for the usual boneheaded online commentary.

What Bankman-Fried and Hanania were seeming to suggest was that the past, in some critical way, had no independent existence — that its entire meaning was as a link in the chain of progress, if not as a function in some ahistorical algorithm. This type of argument is becoming actually more and more common — Bankman-Fried’s clownishness makes the Shakespeare point itself not particularly serious — but there’s a reductio ad absurdum from the notion of an activity. Any activity, goes that mode of thought, is as self-contained a domain as a mathematical set, and the more data is added to the activity, the better, intrinsically, the top practitioners of that activity will be.

The believers in this sort of progress-through-activity point to sports, to gaming, to science, and claim that progress must therefore be a function of all possible fields. Hanania in particular buys into this idea, writing, “No one thinks the best athletes lived 50 years ago, we can see data showing that people are breaking records all the time.” And in that narrative — and Bankman-Fried and Hanania and many other people, I’m sure, actually believe this —the past is just a kind of dress rehearsal for the present, touching and amateurish given that those in the past are always working with seriously limited data sets.

I’m used to these arguments from chess where they actually have a certain merit. Chess is, of course, an inherently limited activity — 64 squares, 32 pieces, and has been that way for centuries — and there is a school of thought within the chess world that holds that the inexorable progress of “scientific” study and then of the computer age makes chess history just a quaint sort of museum piece. There was a lively debate when a top player threw out all his classic chess books, claiming they were worthless, and another when a grandmaster went through games of strong players from the early 1900s and decided that they played at what would now be considered club level. That hypothesis got its empirical verification when, on an overcast December afternoon in 2017, a DeepMind product called AlphaZero played millions of games with itself and promptly reached the highest level of chess play ever. The right way to think about AlphaZero’s achievement is that it is a completely alternative chess history (there was no strategic input from human players as had been the case for previous top chess programs). In that chess history, there is no triumphal tour of Paul Morphy (and subsequent breakdown), no great investment by the Soviet Union in chess thereby turning chess into a front of the Cold War; no challenge of the Soviet machine by Bobby Fischer, with Fischer literally playing out of his mind — and reaching the peak of chess artistry just at the moment he was irrevocably going mad. In the alternative, far more tranquil history, there are just a lot of games leading to steady progress. And to a certain kind of quant mind, it’s actually better that way — with none of the messy and far-from-perfect evolution of chess strategy in the human sphere.

But, even in chess, it’s an absurd claim that the quants make. The point of chess — the reason it evolved in human society — was, first of all, as a way to pass the time; and then, secondly and more grandiloquently, as a means for testing the outer limits of human logic and creativity in a competitively-challenging setting. The pleasure of chess — and it is a real, visceral pleasure — is to, under conditions of stress, find moves, or strings of moves, that are at once logical and beautiful and which tend to come as an immense personal surprise. It really doesn’t matter at all if, to some other form of intelligence, chess is ridiculously easy. It would be like not having a wedding because professional wedding planners or experienced divorcées might do a better job at it than you would.

An argument like this, on the intrinsic value of chess, helps also to revive the value of the past. The past isn’t the warm-up for the present, it’s a closed book, shutting on itself at every instant. I haven’t had the problem of the grandmaster who threw away his whole library — I’ve been keeping a blog on chess history and have really enjoyed doing so. Yes, the quality of play wasn’t as high, but the drama is there, the players pushing at the limits of the form as it had been achieved in their era, and the games lose none of their aesthetic value as time goes by.

It’s somehow much easier to deal with Bankman-Fried and Hanania’s arguments in their chosen field of literature. Hanania, doing his best Bill James imitation, lists three criteria for defining ‘literary greatness,’ involving influence, quality, or relative ability compared to era. But this is like the scene in Dead Poets Society where Robin Williams comes across a similar metric and starts encouraging students to rip up their textbooks. The only metric of these that matters is quality — the ability to make people feel and to make them feel, from the exact same words, centuries later. And it can be argued about what matters in quality, but what’s pretty clear is that no possible metric for quality would be related in any way to the progress-focused measurements of the quants. There’s quality as control over the language (which changes but doesn’t ‘improve’ with time) and there’s quality as the truthful representation of life as it is experienced by the writer in their particular time (and there is of course no reason to think that the future would have any advantage over the past here either). Actually, literature, as many people close to it have noticed, seems to be remarkably resistant to ideas of progress. Erich Auerbach opens his literature survey Mimesis by claiming that Western representations of reality have never caught up to Homer.

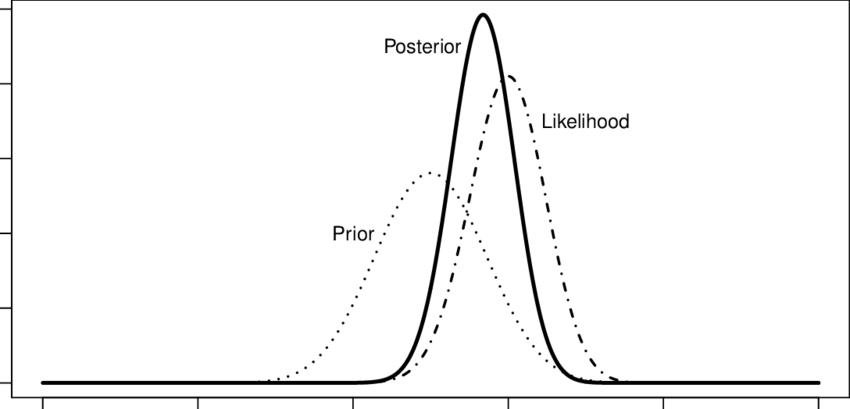

Compared to the direct, sensory, emotional experience that people have had for a very long time to writers like Homer and Shakespeare, the quantitative theories espoused by Bankman-Fried come across as a very thin hypothetical. I have no idea what Bayesian priors are or what they have to do with anything. But I am familiar with a particular cast of thought, which holds that math is true and that activities can be assessed according to the quantitative analysis that’s brought to bear on them (Malcolm Gladwell, Ray Kurzweil, Yuval Noah Harari have in different ways been advocates of this theory). And it seems never to occur to people of this cast of thought that there might be domains that simply aren’t quantitative, that don’t represent some pool of data. The trouble here is that arguments like theirs have become more and more common and have a veneer of logic to them — and AI seems to confirm the premise. So, inane as these arguments may be — of course you don’t use Bayesian priors to try to read Shakespeare — we can expect to be inundated with them. The way out is, first of all, to stop believing in progress; and, secondly, to recognize that the past has an integrity that is inaccessible to us.

The past wasn’t just there to serve us. It deserves our respect.

Shakespeare's contribution to the world is still happening, it's in process. You can walk into most major museums and see a Rembrandt on the wall, and see why he's one of the best painters who ever lived.

"The past isn't dead. It isn't even past."- William Faulkner.