Dear Friends,

This is a new section on the Substack — focused more on history. The initial pieces come from my overflow in working on a novel about World War II. The name comes from a preternaturally wise 8-year-old named Charles whom I once overheard consoling another 8-year-old named Hamilton by saying, “Past is past, future is future, and we can only live in the present.” I actually disagreed, but it seemed like not the thing to do to argue metaphysics with an 8-year-old, and especially with Hamilton as upset as he was. So consider this section an extended rebuttal to Charles and a meditation on how the past interacts with the present.

Best,

Sam

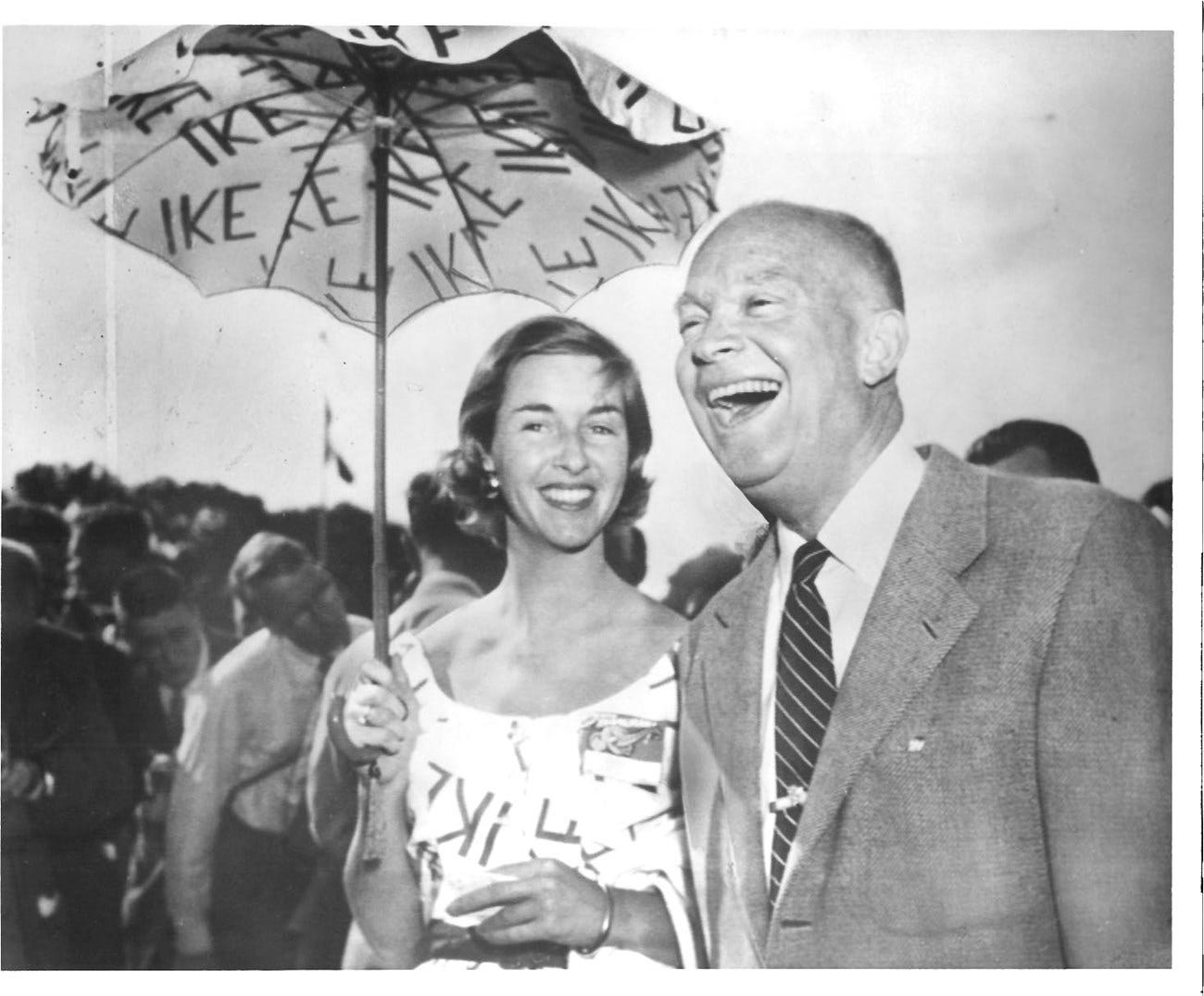

DO I LIKE IKE?

There’s something about Eisenhower, more than just about any president, that recedes behind the cultural memory. He seemed to be embalmed from the beginning — or like he was the fairy tale version of himself. Merle Miller, who wrote a biography of him, complained about the “myth of suffocating dulness — a civic elephantiasis.”

In a way, the legend was there before Eisenhower himself. He was appointed to head the Allied forces in the European theater in the middle of 1942 when he was, at the time, a completely obscure staff officer — and that suddenly catapulted him to the forefront of the national consciousness. He was the perfect image of charm, of middle American virtues, of unassuming-and-yet-dogged generalship before he’d led a soldier into a combat — or, in fact, been anywhere close to combat himself. If his rise to the (very capable) Supreme Command of the Allied war effort was improbable — acquaintances of his muttered about the uncanny “Eisenhower luck” — his smooth ascent to the presidency afterwards seems, similarly, to be drawn from some down-market adventure story.

That’s the overwhelming sense of Eisenhower’s presidency — how easy it all was. If, in reading Caro’s account of Johnson, everything is of a man swimming upriver, fighting his way to the presidency against almost unimaginable odds, Eisenhower seems to float into his position and then to occupy it as lightly as possible, constantly insisting on the limits of his own power and to a surprising extent banishing politics from his administration. The 1956 election, for instance, is, from our perspective, almost unimaginable in its lack of rancor or partisanship — negative attacks seemed not to exist; and Eisenhower, preoccupied with Suez, barely paid attention in the campaign’s closing days.

As Stephen Ambrose points out in his Eisenhower biography, it was this ease that in its way was the greatest flaw of Eisenhower’s. When it came to what should have been the great issue of the time, desegregation, Eisenhower didn’t lead at all. “His refusal to lead was almost criminal,” Ambrose writes. His style (which incidentally had always been his leadership style in World War II) was to be more of a “chairman” than a commander, and, when it came to desegregation, that resulted in a sort of paralysis, an unwillingness to rock the boat or exercise real moral leadership — as he could have readily done by enthusiastically endorsing Brown v. Board of Ed or attempting to enforce it.

But what I wanted to reflect on here wasn’t so much assessing Eisenhower as understanding how drastically American presidential politics has deviated from his vision, or even from his unspoken assumptions, of how it worked.

What the “chairman” approach stemmed from, I believe, was Eisenhower’s core personality, which, deeper than that of a general, was a football coach’s. He badly wanted everybody to be playing on the same side — which included the press, the party system, the military establishment — and was deeply distressed whenever anyone lacked the sense of patriotism and public service that was so natural to him. Joseph Alsop, of The New York Times, was “about the lowest form of animal life on earth” for having printed leaked information on secretive government programs. Nixon, among others, was deeply suspect for “never considering a problem from any point of view other than partisan political considerations.” And, most critically, the defense establishment needed constant batting-away for its tendency to soak up the entire national budget. “I am beginning to think that the Air Force is not concerned over true economy in defense,” Eisenhower drily remarked in a 1960 meeting.

To a remarkable extent, Eisenhower really did succeed in the “common sense,” everybody-on-the-same-team approach to government: he maintained a balanced budget (which may well have been his proudest achievement) and he kept the warmongers in the defense establishment largely in check. The concern he had was that his successors would be both more imbalanced in their leadership style and more credulous when it came to the military establishment — that they wouldn’t catch on to the games that the military constantly played. That seems to have been a very warranted fear. Kennedy promptly fell for a piece of Air Force budget chicanery and made the “missile gap” a cornerstone of his 1960 campaign — which led in its turn to a fresh arms race with his office-taking. And Eisenhower, at an astonishingly paternalistic moment, found himself berating a disconsolate Kennedy after the Bay of Pigs for having tried to govern on his own, with a handful of advisors, without seeking the balanced advice of the entire NSC.

Kennedy’s missteps in 1961, in a way, set the tone for the next 60 years of American history. The balanced budget is sooner or later completely forgotten. The defense establishments end up, at various moments, with carte blanche and runaway budgets — and the whole idea of a presidency governed by Abilene common sense comes to seem like the most hoary of national myths.

What’s striking about Eisenhower is, first of all, that it was possible — but, also, that it rested largely on a tremendous exercise of presidential will. You may not remember 1954 as being a particularly bellicose year, but it turns out that, in 1954, the Joint Chief Staffs recommended the use of atomic bombs no less than five different times — all on preemptive strikes against China on such burning crises as Quemoy and Matsu — and the keeping of the peace rested, above all else, on Eisenhower’s prudence and willpower (which was, more than anything, the result of his command experience and of his understanding of the hysterical tendencies of other generals).

The criticism of Eisenhower — apart from his slowness on desegregation — was his inability to effectively control the arms race and U.S. military buildup. The CIA expanded greatly under his watch, his attempts at a test-ban treaty with the USSR were sabotaged by his own orders to continue U-2 overflights, and the nuclear buildup raged through most of his administration until he belatedly attempted to pull it back in the late ‘50s. In that context, Eisenhower’s famous “beware the military-industrial complex” line comes across like the cry of a hostage from a captivity that he had constructed himself. But, taken step by step, the arms buildup is more understandable. It really was a difficult and puzzling set of circumstances — Eisenhower called it “hellish.” It’s easy, in retrospect, to remember atomic bombs and then jump straight from there to ICBMs and to forget that that step required a decade’s worth of technological evolution, with missiles gradually replacing the bomber fleets, and with its being unclear the entire time where the Soviet Union actually stood in its nuclear arsenal. From the game theory perspective, it seems somehow hard to argue with what Eisenhower did — rejecting the entreaties of his advisors who wanted him to make use of the nuclear advantages he had, for instance against China in the early ‘50s, while continuing the arms buildup until it was clear that some parity had been established with the Soviet Union both in terms of armaments and the ability to deliver them and then trying to dial back everything once proliferation became an issue and the race had reached the point where, as Eisenhower put it when reviewing the 1960 military budget, “How many times do we have to destroy Russia?”

As popular as Eisenhower was during his presidency — “he was so comforting, so grandfatherly, so calm…that he inspired a trust that was as broad and deep as that of any President since George Washington,” writes Ambrose — there has been a curious sort of ingratitude towards him and his whole era since then (maybe just the karmic balancing-out for how smooth his ascent was). The ‘50s have become synonymous with staid and boring. Eisenhower’s grandfatherly style strikes us as naive and somehow unattractive. But the point is that there may be a lot to learn from Eisenhower, and especially at the moment when the body politic appears to be cracking. The ‘50s are looking a lot better than they have in a while — a widely-available middle class lifestyle; an absence of hyper-partisanship in national politics. And much of what worked about the era is directly attributable to Ike. There’s the insistence on the balanced budget (now vanished even as an aspiration), the ability, even in the midst of Cold War hysteria, to maintain executive checks on defense spending (also a lost art), and, maybe above all, the emphasis on civility, teamwork, common sense in virtually all of his communications. To a surprising extent, Obama may have been the real heir to Eisenhower, but the national mood was already far gone by then. In dealing with Eisenhower’s legacy, what we’re more thinking about instead is a matter of picking up the pieces — if the hyper-partisanship can somehow be brought back into the bottle, and if deficit spending is somehow wound down, then the best we can imagine is a government run lightly, with restraint and common sense.

My answer to your post is yes, I like Ike. His caution hurt civil rights, but it was the same caution at work that held the military in check. Historical figures almost never get credit for restraint., but if Ike prevented the use of atomic weapons against China, that is as heroic of a restraint as i can imagine.

Thinking of Ike's reluctance and silence on de-segregation, I've sometimes wondered whether the distinctly Southern cast of the professional military of his time may not have played a role in framing his ideas about the possibilities for including African-Americans in the greater American project. And, I've wondered, too (though this is a very notional and perhaps flimsy speculation), whether his love of the decorums of the Augusta National golf course, and the seductions of a certain tory Georgia, may not have contributed to his aloofness from the claims of the civil rights movement.