Dealing With The Russian Right

Limonov, Dugin, Ilyin and the Importance of Knowing Your Enemies

Around 2014, I got into an odd phase in my reading. I became obsessed with – of all things – the Russian writer Eduard Limonov, first through a sui generis biography about him, Limonov, by the French intellectual Emmanuel Carrère and then through his own memoir/novels, It’s Me, Eddie (a tepid translation of the book’s French title, The Russian Poet Prefers Big Blacks) and His Butler’s Story.

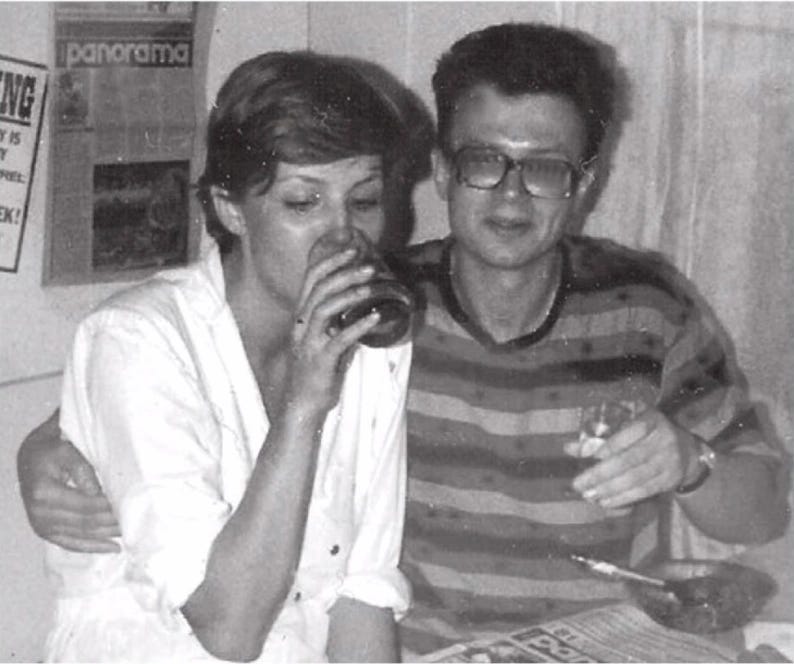

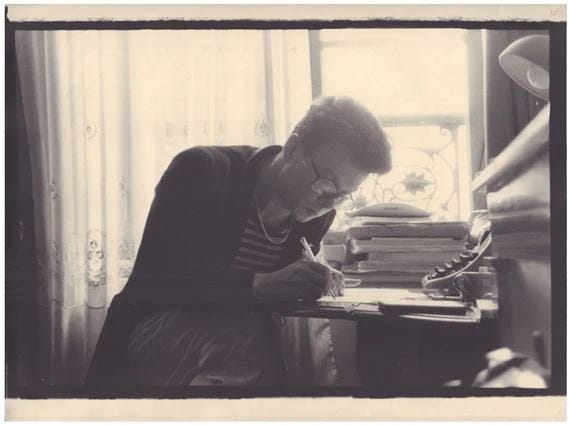

I was around a lot of cosmopolitan Russians at the time, and everybody was annoyed with my new fascination. “He’s just this really weird, terrible guy,” I was told. It was like I was going around recommending to people that they read, I don’t know, the complete works of Lyndon LaRouche. Limonov had had a very curious career. He had been a semi-prominent Soviet poet, emigrated to New York in the 1970s, wrote It’s Me Eddie about that experience – bilking the welfare system and his millionaire boss, being homeless and sleeping with an array of street people, both men and women. The book was ignored in America but became a sensation in France and justifiably so – it’s really excellent, in the scabrous tradition of Céline, Knut Hamsun, and Henry Miller. And then in the 1990s, when the dissidents were supposed to return to Russia and create democracy, Limonov surfaced instead at the siege of Sarajevo, fighting on the side of the Serbs. “It was about as strange as discovering that an old school buddy had gone into organized crime or blown himself up in a terrorist attack,” wrote Carrère, who had been part of the Parisian cosmopolitan scene that lauded Limonov in the ‘80s. The structure of Carrère’s book mirrored my own fascinated repulsion – the feeling that there was something indecorous about giving any serious attention to a crank like Limonov while at the same time insisting that this was important, that Limonov was emblematic of something crucial, of one conception of the world giving way to another, of our potted frames of reference being inadequate to understanding what really was happening in the post-Soviet space.

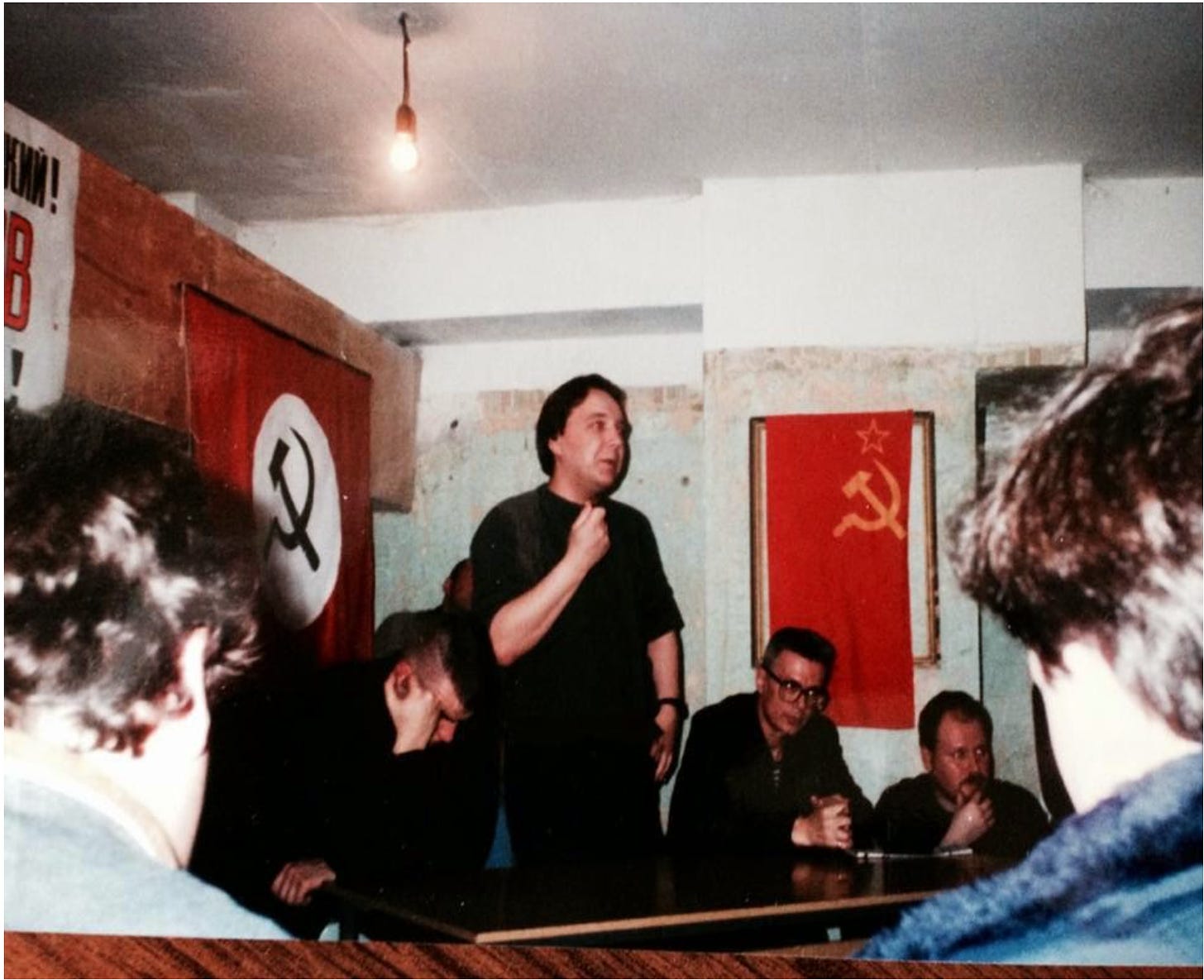

After Bosnia, it got worse. In 1993, Limonov together with Aleksandr Dugin founded the Nazbol party – a hard-to-believe combination of Nazism and Bolshevism, the flag featuring, sure enough, the colors of the Nazi flag enclosing a hammer-and-sickle. And that was pretty much where Limonov still was politically when Carrère’s book came out two decades later – he had experienced everything that the liberal West had to offer and had chosen instead to be and to remain an avowed Fascist. The Nazbols had never really moved closer to power and the Russians I knew regarded Limonov as fringe, but Carrère had a different view, which was that he very much spoke for a certain strain of the Russian spirit and that, as a kind of political happenstance, Putin had subsumed Limonov. “The difference between Putin and Limonov,” Carrère wrote, “is that Putin succeeded.”

To an outsider there was something reptilian and technocratic about Putin – “the man without a face,” as Masha Gessen titled her biography of him – but through Limonov, Carrère was arguing, it was possible to understand Putin’s appeal. And his real self wasn’t the soft-spoken pragmatist that the West saw throughout the 2000s – it was more interesting and more terrible.

Because, in the early days at least, Limonov was cool – and, with him, there was a certain taste and worldview. Power was appreciated for its own sake. Politics was understood to be, entirely, an extension of the mentality of the gang – ‘I’m Looking for a Gang’ was the title of an article Limonov wrote soon after his return to Russia. And violence was seen to be salutary, a person’s composure with violence the truest test of their character. “There are two kinds of people, there are those you can hit and those you can’t – not because they’re stronger or better trained but because they’re ready to kill” is Carrère’s description of Limonov’s childhood mindset. “That’s the secret, the only one. And nice little Eduard decides to defect to the other camp: he will become someone you don’t hit because you know he can kill.” Which, by the way, is very reminiscent of Putin’s attempt to portray his own childhood in his 2000 campaign biography – its central theme being that Putin was a holy terror in courtyard fights, instigating fights and carrying them out to the bitter end. “You are trying to insult me,” Putin told his biographers when they pushed back on this narrative. “I was a real thug.”

In Limonov’s world everything was done with swagger and a sly sense of humor – and that sense of humor, I believe, is key to the whole phenomenon of the Russian right: it’s the snickering of the backbenchers as the spitballs land on one of the teacher’s pets, the moment of delicious anticipation just before the teacher starts to berate probably the wrong culprit, the refusal of the rest of the class to say who really did it, the strenuous denials of the guilty party, the suggestion that maybe the teacher’s pet threw the spitballs at themselves, that maybe, ultimately, the teacher is to blame. But that sense of humor belied an amoral seriousness – a sense that there was no higher truth than that of the gang holding the class hostage.

I got to be very shy about my interest in Limonov – about the trips I took to the public library to read his novels – but I wish I hadn’t been. Partly as a result of having read Limonov I paid attention to Michael Savage when I first heard him on the radio and as a result of having listened to Savage I was, let’s say, less shocked than the average Brooklynite when Trump appeared at the top of GOP polls in 2015 and then never dropped from there. A good lesson for me, in other words, in why it’s important to listen closely to your enemies. And if I’d continued with my course of reading I would have made it to Limonov’s erstwhile partner Aleksandr Dugin and to their intellectual ancestors Lev Gumilev and Ivan Ilyin and wouldn’t have been surprised at all when Putin invaded Ukraine on February 24th – because the whole ideology behind it was laid out very cogently in this swathe of Russian right-wing philosophy.

Since then, I’ve been cramming. I haven’t really had it in me to get through much of Ilyin or Gumilev but Timothy Snyder does a brilliant summary of Ilyin in his The Road to Unfreedom while Mark Bassein tackles Gumilev in The Gumilev Mystique. I did make it through several volumes and talks of Dugin’s, and – if you can stomach it – his Putin v. Putin: A View From The Right is the best single source I’ve come across for understanding what’s really driving the Ukraine invasion. Dugin – rumpled, erudite, always underestimated – is the most determined modern standard-bearer of the strain of the Russian intellectual tradition that makes Westerners start skipping pages when they’re reading Dostoevsky or Solzhenitsyn. It’s Slavophilism, the Third Rome, Orthodoxy and the Old Believers, Kievan Rus – a real yawn fest until it leads to civilians being shot off bicycles in Bucha and Russia withdrawing, for the foreseeable future, from the community of nations.

One thing that reading Dugin does is it helps to sweep aside a few half-hearted interpretations of what Putin is up to. It’s not some sort of geopolitical ‘technocratic’ response to anything that NATO or the ‘The West’ are doing; it involves a view of Russia’s inherent place in the cosmos to which neither the West nor neighboring nation-states have any right to interfere. And it goes well beyond this timid catch-all phrase ‘illiberalism,’ which implies that liberalism and its adversaries are all still operating in more or less the same political discourse. We’re not. The word for what Dugin, Limonov, Gumilev, and Ilyin are espousing is ‘Fascism’ – they say it proudly – but Fascism with a particular flavor, without the distracting emphasis on racial theories, and focused on the core, on pure power, authoritarian, messianic, capable of generating not only its own morals but its own reality.

I find all of this to be very clarifying. It’s like reading Kaul Haushofer or Alfred Rosenberg or, why not say it, Mein Kampf, a sense of coming across a worldview that has a logic of its own, a charisma, that is not-to-be-taken-lightly, and that is absolutely, almost symmetrically, inimical to everything in the Western liberal tradition. As Ilyin put it, with his customary brutality, “Politics is the art of identifying and neutralizing the enemy.” We – as the West – have been identified as the enemy. And, in the thinking of Ilyin, Dugin, and, I am convinced, Putin, the antagonism towards the West is not seen in Cold War terms as a debate about economic systems or negotiation of geopolitical spheres of influence; it’s a mystical opposition. “The entire span of Russian history is a dialectical struggle with the West,” writes Dugin. “The U.S. always has and always will be fighting a Cold War against Russia.”

In Dugin’s cosmology, the arch-villain is – of all people in the world – John Stuart Mill. Dugin’s idea is that liberalism, defined by Mill as ‘negative liberty,’ is intrinsically a nihilistic belief system. ‘Negative liberty’ means ‘freedom from,’ which, when pursued to its logical end, means deracination, loss of identity, loss of purpose of any sort. Liberalism can present a nice enough appearance when in opposition – “when there is an illiberal society liberalism is positive,” writes Dugin – but once liberalism triumphs, as it has in the aftermath of the Cold War, the illogic at its core leads, in short order, to decadence and terminal decline. “We have now discovered the purest essence of liberalism: freedom from everything, which is nothing more than pure nothingness and absolute nihilism,” writes Dugin.

The terminal decline of the West is evident in what Dugin calls the ‘dehumanization of man and the loss of gender identity’ – and the ‘rhizomatic existence’ that follows from the loss of ‘dasein’ and a sense of community built on blood and soil. It is evident also in the West’s desperate attempts to antagonize and vilify Russia, of which NATO’s expansion and American influence in Ukraine are symptomatic. But, for Dugin, the West’s decadence is useful from a dialectical perspective – allowing Russia and the ‘Eurasian’ sphere, of which Russia naturally is at the head, to formulate a ‘counter-hegemony.’ “That does not mean that postmodernism and globalization are good to their core. They are not good; they are the worst of all evils,” writes Dugin. “But if we look closely at the structure of this evil we will be able to formulate the most radical and decisive antithesis, to reach the very depths of our national soul.”

And the national soul is, it almost goes without saying, collectivist, Orthodox, and, above all, authoritarian. “Russia is politically structured on the principle of vertical symmetry. The one at the top is everything. The higher up and the more authoritarian the ruler is the closer he is to the masses and the more stable his rule,” writes Dugin. “Call it what you will. It’s Russian. It was and most likely will be.”

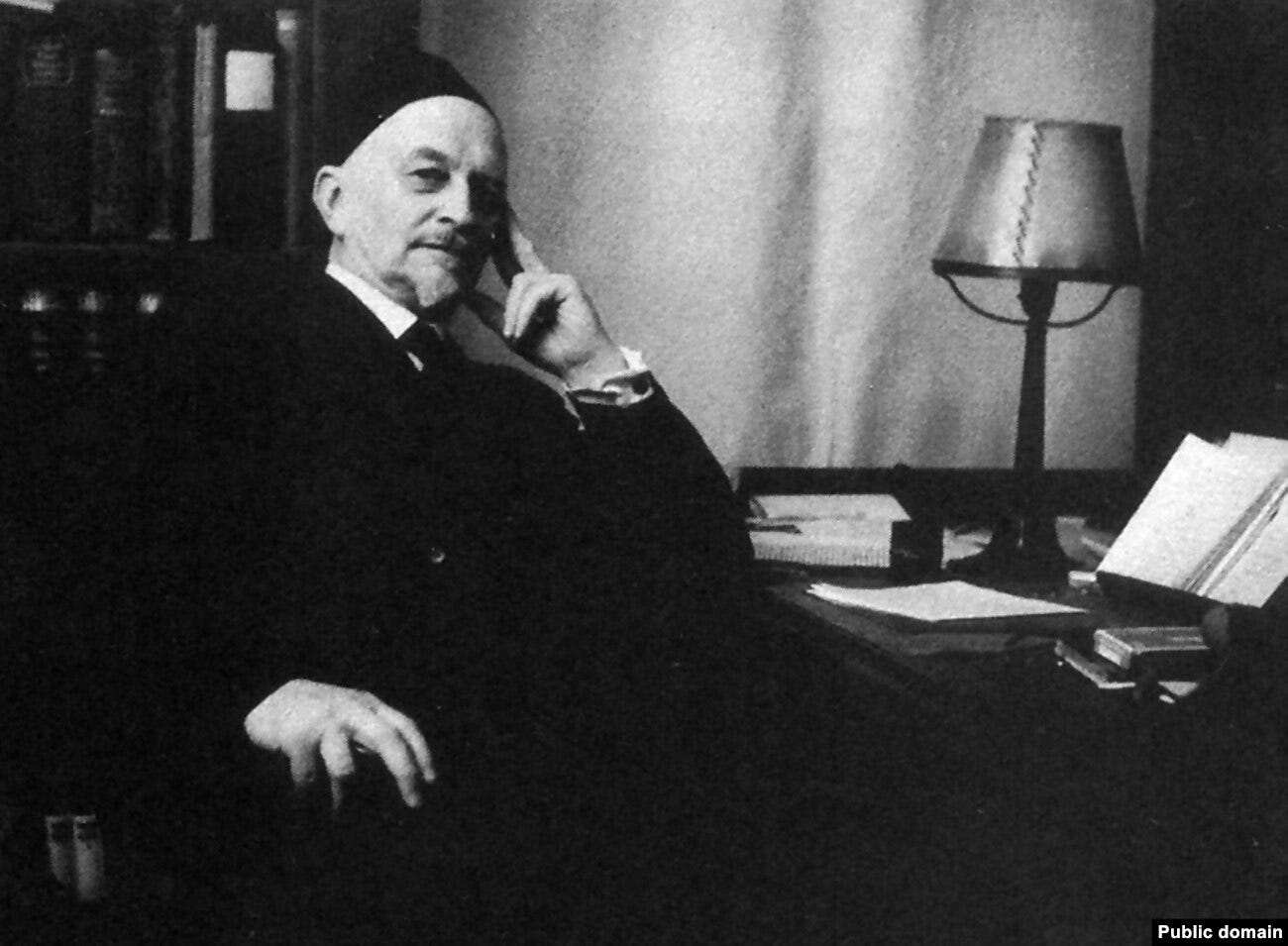

Dugin’s is a kind of nice guy version of Ilyin’s philosophy. Through a torturous logic, Ilyin construed Christianity itself as insisting on violence, the idea being that the creation of the world itself had been an act of evil and the pure Russian soul provided a path towards primordial totality through a ‘chivalrous’ and violent self-sacrifice. “Loving God means a constant struggle against the enemies of the divine order on earth,” wrote Ilyin. “He who opposes the chivalrous struggle against the devil is himself the devil.” Meanwhile, Gumilev, who has a certain sentimental appeal to cosmopolitan types (he’s the son of Anna Akhmatova and Nikolai Gumilev and a starring figure of Akhmatova’s ‘Requiem’) veered hard to the right during a Gulag imprisonment and made free use of pseudoscience and racist theories in developing his view of the Russian people as an ‘ethnos’ as immutable and endogamous as an animal species.

From Dugin’s perspective, Putin has been an equivocal figure – his heart seems to be in the right place, that is with Ilyin, etc, but he has been moving painfully slowly in carrying out the sacred task. In an interview in 2001, Dugin said (this is also the epigraph of Putin v. Putin), “Putin is the ideal ruler for our period. He is a tragic figure. He has a horrible entourage around him, a sea of despicable worms who are fouling up the entire field of his movement. And he is methodically and steadily, bit by bit, clearing away this dismal legacy. He is like an alchemist turning black into white.” The ‘despicable worms’ are the liberals who had influence in the Yeltsin years – “radical pro-American stool pigeons” – and Dugin’s conception is that Putin over the next decade-and-a-half tacked back and forth, presenting a formula of ‘patriotism plus liberalism,’ placating the West, testing out democracy, before gradually coming around to Dugin’s position (which he may have secretly held to all along) and embracing the hard right.

There was always little question from this perspective that Putin is the authoritarian ruler that Russia should have – the power that he amassed in the early 2000s proved, just by itself, his fitness for the role. “Power comes by itself to a man of destiny,” wrote Ilyin. And Dugin reports, with pleasant surprise, that in the late 2000s a ‘high-ranking official in the Kremlin’ told him, “We owe everything to Carl Schmitt.” This proved to Dugin that Putin was very much on the right track – a vision of politics utterly free of ethics in which the state embodied in a sovereign ruler created its own law. “The most important function of the state is to retain order and the state should be free of ideological convictions” is Dugin’s summary of this viewpoint. (From within Dugin’s world, it’s a bit impolite to point these things out, but it’s worth saying here that both Schmitt and Ilyin were Nazis – not people who had certain Nazi tendencies, not people sympathetic to Nazism, actual Nazis, Schmitt a member of the Nazi Party, Ilyin the author of the charming 1933 essay ‘National Socialism: A New Spirit,’ and that both of them retained their Nazi convictions for the rest of their lives.) And, as encouraging as Dugin had found Putin’s Schmitt-inflected realpolitik, the hope was that Putin would take things further and embrace a messianic vision of Russian might – and he seemed to be on the verge of doing that at the time Dugin wrote Putin v. Putin. “Putin is on the threshold of a new role – as a man of destiny,” Dugin wrote. “All that remains is for Putin to become the thing that his sworn enemies see him as.”

There has been some skepticism among veteran Putin-watchers, even those who are very critical of him, about how much Putin owes to Ilyin or Dugin. Marlène Laruelle, a French academic who wrote a terrific chapter on Dugin in her book Russian Eurasianism, claims that the whole project of trying to identify ‘Putin’s guru’ or ‘Putin’s Rasputin’ is a kind of parlor game by journalists and academics who are glazing over nuances. “The Russian presidential administration cultivates a plural doctrinal market with a flock of advisors offering several mixed ideological products for public consumption,” she writes. She points out that Dugin has never had any real power under Putin’s régime and that, while Putin has quoted several times from Ilyin in his speeches – Timothy Snyder makes much of this – the excerpts from Ilyin are anodyne and incorporate very little of his overtly Fascistic thinking.

But I don’t know. As far as I can tell, there’s an almost perfect match between Putin’s behavior on his return to the presidency in 2012 and the far-right ideology of Dugin, Ilyin, et al. “Russia will either be great or it will be nothing,” he said. In 2008, asked by Angela Merkel what his greatest mistake had been, he said, “To trust you” – meaning the West. Michael McFaul, who was the U.S. ambassador in Russia at the time of Putin’s return to the presidency, wrote of “dealing with an entirely different interlocutor, one with fixed and flawed ideas about the world in general and the United States in particular.” Dugin himself seems a bit touchy about his lack of direct influence over the Putin administration but insists, in the introduction to Putin v. Putin, that he is, in fact, the ‘grey cardinal.’ “Today the members of Putin’s entourage are speaking my language,” he writes. “True, I am little-known but only because thieves never reveal the source of their wealth.”

One of the places of near-perfect overlap between Putin’s actions and the preoccupations of the far-right is Ukraine. Ilyin refused to write the word Ukrainians unless it had quotation marks around it because, of course, Ukraine belonged intrinsically to Russia. “The battle for post-Soviet space is the battle for Kiev,” writes Dugin. In 2008, still in his ‘liberal’ phase, Putin had placidly said that “Crimea is not a disputed territory…Russia has long recognized the borders of modern-day Ukraine.” But by 2014, when the hard-right turn had taken place, Ukraine and Russia were “one people with ancient Rus as a common source and cannot live without each other.” And in 2021, Putin would call “modern Ukraine entirely the product of the Soviet era – shaped for a significant part on the lands of historical Russia.”

There are various cynical ways to view this – Putin creating an external enemy in order to bring his propaganda machine into top gear and cement his rule internally – but the most frightening and probably most accurate way to construe Putin’s fixation on the absorption of Ukraine is that it’s sincere and mystical. “Ukraine is the original lost unity, the heart and soul of its people,” wrote Ilyin. In the conception of divine Russia, with its messianic mission, Kievan Rus is the cradle, and ‘Novorossiya’ – a concept introduced by Catherine the Great and rekindled by Putin in 2014 – makes Ukraine inalienable to Russia. Putin’s 2021 essay ‘On the Historical Unity of Russia and Ukraine’ – a surprisingly schoolboyish way to declare war – echoes Ilyin in viewing Russia as the eternal innocent and out of the goodness of its heart, through a distortion of the Western influence of Bolshevism, creating Ukraine on the map. “One fact is crystal clear: Russia was robbed, indeed” is Putin’s analysis of this overly magnanimous gesture.

In this conception of the world, Ukraine becomes not only the ‘brother nation’ to absorb in Russia’s inherent right to expand but the site of the showdown with the West. “This war is not against the Ukrainians,” wrote Dugin in 2014. “It is against the liberal world (dis)order. We are not going to save liberalism per their designs. We are going to kill it for once and for all. Modernity was always essentially wrong and we are at the terminal point of modernity.” A really horrific article published in RIA Novosti on April 4, 2022, holds that the “Nazi (Bandera) type of Ukraine is the enemy of Russia and the West’s tool for the destruction of Russia” and that “the collective West is the designer, source, and sponsor of Ukrainian Nazism.” On Russia’s Channel 1, Margarita Simonyan, the RT editor-in-chief, says that the war at the moment is not really with Ukraine – “it’s NATO, all of their arms, their weapons, their equipment, their trainers, their mercenaries being used against us.” Ilya Kvya, a pro-Kremlinite formerly in the Ukrainian Rada, calls on Telegram for a “nuclear strike to put an end to the confrontation with Ukraine’s authorities and the entire West.”

And so on. I’ve been very affected, since the first time I read it, by a line of Czeslaw Milosz’s from The Captive Mind: “It was only towards the middle of the twentieth century that the inhabitants of many European countries came, in general unpleasantly, to the realization that their fate could be influenced directly by intricate and abstruse books of philosophy.” For me that’s been a kind of coat-of-arms as an intellectual. In a materialist era and culture, where all political events are explained through something related to the immediate news cycle or, at the most ‘theoretical’ level, via pop psychology, explanations involving history, let alone philosophy, are frowned upon. In my view that’s an incredible mistake.

The lesson of the Nazis – which was not at all clear to politicians in the ‘20s or ‘30s – was that the Nazis had an alternate view of history and of morality, that it was internally coherent and fully practicable while at the same time inimical to everything in the Western liberal tradition. And for anybody willing to wade through a lot of dense text, it was all there on paper – an ideology of race and power that had been developed over the better part of a half-century. The theories underlying Putin’s version of Fascism have, if anything, an even older and more storied pedigree. They connect to very ancient and resonant strains within the Russian psyche, and their theorists are nothing if not erudite and historically-minded. For Dugin – the most erudite and historically-minded of them all – the really critical turn is in the 17th century, with John Locke and the Peace of Westphalia and a Western fixation on limits, both in the construction of the ‘rights of man’ and the framing of the autonomous nation-state. With a disarming magnanimity, Dugin claims that he is not arguing against that movement – it’s the West’s business – but it has nothing to do with Russia’s separate and sacred direction, which is connected to hierarchy, to unlimited sovereignty, and to empire. “The state is an artificial pragmatic construction, desacralized and devoid of telos, purpose and substance,” he writes. “On the contrary, the empire is something alive, sacred, and replete with purpose and essence: something that has a higher destiny.”

In 2014, in the midst of the Crimean invasion, Angela Merkel told Obama that Putin had lost touch with reality – that he was “in another world.” In the somewhat sneering way that this was reported in the West, that meant that Putin had lost his marbles, that he was ranting and raving about something to do with medieval history and Russia’s destiny. But there’s another way to take that – and, actually, Merkel may have meant it differently. The point is that Putin wasn’t insane but had simply moved into a different intellectual framing of reality, a path that had been well paved for him by thinkers like Ilyin, Gumilev, and Dugin. As late as 2021, in ‘On The Historical Unity of Russia and Ukraine,’ Putin was fully capable of seeing the other side. On the subject of the Ukrainian nationality, he wrote, “Of course, some part of a people in the process of its development can become aware of itself as a separate nation at a certain moment. How should we treat that? There is only one answer. With respect!” And then, in a breathtaking sleight-of-hand, explained that that principle did not apply in this particular case. “The fact is that the situation in Ukraine is completely different,” he continued. “Our spiritual unity has been attacked.”

In other words, what we were dealing with was a clash of paradigms. That’s very different, by the way, from the suddenly-popular ‘clash of civilizations,’ which implies that civilizations are capable of acting only according to some sort of primal imprimatur, that they have a particular cultural ‘destiny’ – a theory that is at its core indistinguishable from Gumilev’s. My point is that there is individual agency and choice. A figure like Putin is capable of flipping a switch and decisively shifting Russia’s mentality onto a different intellectual track. The evil that this can do is incalculable, but at some level, interestingly enough, everything that follows remains with the domain of intellect and philosophy. And there is a certain valuable work that intellectuals are capable of doing within the changed landscape – grappling with the ideas of the Russian right, recognizing them as components of an ideology which possesses both internal coherence and genuine charisma, and making the case for the opposing position. Dugin has done us a favor – he has, with startling specificity, identified as his enemy the very core of the Western liberal tradition: John Locke, John Stuart Mill, Karl Popper, the ‘rights of man,’ the Peace of Westphalia. In other words, everything that we must stand for.

Wow- this article really needs a bigger audience. Not that that would actually help us deal with anything, except perhaps our own (my own) bewilderment.

It is a good piece. Something about it feels a little outdated about it though. We know that the Russian invasion of Ukraine isn't exactly a great thing.