Curator

Andrea Dworkin Rehabilitated, Isaac Bashevis Singer Scrutinized, the Guggenheim "Canceled"

DWORKIN AS PROPHET

I’m grateful to this piece by Amia Srinivasan putting Andrea Dworkin at the forefront of discussion. She’s absolutely right - Dworkin is a pivotal thinker for understanding where we are sociologically. And if she seemed like a curiosity amidst the sex-positive feminism of the ’70s and ’80s, she’s been if anything gaining influence in afterlife. “Since the rise of Trump and MeToo…Dworkin is being rediscovered - and rehabilitated - by a new generation of young women,” Srinivasan writes.

The wave of prudishness - Christine Emba, Michelle Goldberg, Louise Perry, MeToo in general - is all deeply indebted to Dworkin. And the really critical conceptual shift is hers - that an individual performing a ‘consenting’ sex act does not necessarily have autonomy over themselves; that the sex act itself implies a certain power dynamic which has its own inalienable coerciveness.

Other people were making variations of this point, but there always seemed to be some hope for a harmonious solution - a desexualized workplace, for instance, as per sexual harassment law, but relative sexual permissiveness in non-work-settings. Dworkin really was an absolutist, though. For her, heterosexual sex itself was inimical to feminism, and there was no question of which was of higher priority. “I’d give my life to the movement and for the movement,” she wrote.

There was an irony here that was not lost on other feminists. By claiming that the inherent power dynamic of the sex act made it impossible for a woman to genuinely consent to sex, she restored, from a very different direction, the old patriarchal argument that held that sex was dangerous for women, was different for men and for women, and that social mechanisms of some sort were needed to control the more volatile aspects of female sexuality. But more and more, as Srinivasan correctly notes, it seems to be Dworkin who’s winning. The sort of second wave of MeToo - the Aziz Ansari piece, etc - owed a deep debt to her. It wasn’t just a matter of invoking sexual harassment law or the sanctity of the workplace - the problem wasn’t even power imbalances; the problem was sex itself, that the sex act (or in the case of the Ansari piece overt sexual energy) was by itself a breach of the social contract between two people and therefore subject to societal censure. And the spate of recent writing claiming, as Christine Emba puts it, that “straight people need better rules for sex” is similarly Dworkin-inflected. Sex is dealt with in the language of ‘rights,’ as a kind of odd sub-clause of the social contract, and the usual approach is to see it as something that can be disposed of, an add-on that can just be stricken out. Louise Perry comes up with the novel idea of no sex outside marriage (or the intent to marry). Srinivasan asks if there is ‘a right to sex’ and concludes - as far as I can tell - that there is not.

I’ve been frustrated with this set of arguments before, which, I think, are employing the wrong terminology and standards to deal with sex, and it’s useful to trace a few of them back to Dworkin and her uncompromising set of beliefs.

For me, the main point - that penetrative sex equals rape (“violation is a synonym for intercourse” is what she actually wrote) - is a logical non-starter and, from an argumentative point of view, invalidates a great deal of what Dworkin has to say. The counter-argument is obvious enough and doesn’t need to be articulated at much length - it’s the birds and the bees, the fact that we are mammals and this is how we reproduce, that this whole sex thing wasn’t really our idea to begin with. To decry penetrative sex as inherently wicked, as Dworkin does - putting her in the camp not only of restrictive patriarchy but of Augustinian sex-is-a-sin thought - entails a very different approach to sex than anything in nature. To a baffling extent, our society over the last few years, at least the progressive left, has been willing to make itself over in that direction. A few technologies - in vitro fertilization, gender reassignment surgery, etc - suggest that biology is actually contingent, and that tech and the logic of rights combine to create a sort of extra-biological future. And what can I say to that? Well, I guess that I’m a purist, that I don’t think it’s exactly a great idea to supersede biology, that, for me, we lose something crucial about being human if we drift too far from our sexuality and that any viable society has to take in the reality of sexual desires instead of pretending (this was the mistake of the Augustinian centuries) that they are somehow transcendable.

On the other hand, Dworkin is really right about something which, ironically enough, is even closer to biological determinism - the sense that gender is inherently a conflict. Both the reigning paradigms of Dworkin’s era posited that some sort of sexual harmony was possible - the older patriarchal model with its ‘marriage plot,’ the belief that the nuclear family structure was equally fulfilling for both men and women; and the sexual revolution model with the belief that liberation, the exploration of desire unconstrained by convention, would result in a very similar experience for women as for men. Dworkin perceived that both camps were naive. Simply put, men and women had inimical interests in sexuality, and Dworkin’s brand of feminism held that those interests were so divergent that no real reconciliation was possible, it was crucial for her as a woman to be on the side of women and not to worry at all about how her strictures would affect men.

That attitude moves her much closer to an ancient vision of gender politics - to something like Trojan Women or what Nietzsche called the Greeks’ ‘cheerful pessimism,’ the sense that there simply were insuperable conflicts in human relations, that the reconciliation of those conflicts when it occurred was something close to a miracle and to be grateful for, but there should be no expectation of some one-size-fits-all, collectively satisfying solution.

The ancient consensus on this was that the war of the sexes was the deepest, most fundamental conflict of all. A tale like that of the Atreides presents a series of archetypal figures conducting hostile, not to mention brutal, actions against the opposite sex - Agamemnon against Iphigenia, Clytemnestra against Agamemnon, Orestes against Clytemnestra, the Furies against Orestes, and the trick is that all of them are right, each one of their acts is moral as per the circumstance and the gendered role that the characters find themselves in. And the solution, ultimately, is politics on an adversarial, confrontational model - each side advocating strenuously for itself but with the weapons employed transmuted to something that’s a little more peaceful and, ultimately, harmonious.

Srinivasan’s interpretation of Dworkin has only one side of it - the argument that Dworkin more clearly than other feminists saw the extent to which misogyny and patriarchal power structures were rooted in sexuality. “Dworkin [is] the feminist we now need….to understand why it is that, after all his time, so many men appear to still hate women,” Srinivasan writes. But politics is never a one-way street. Dworkin’s formula of penetrative-sex-as-rape restores a very old myth, the myth of woman as an innocent, woman incapable of having agency over her own decisions. Feminism worked tremendously hard to overturn that paradigm - to insist on agency for women, which entails, at the same time, accepting responsibility for actions. And, actually, the last thing Dworkin would have wanted was to diminish female agency. Her point that gender-is-adversarial welcomes female agency while implicitly recognizing that men at the same time work for their own interests in the political sphere. And as far as her legacy goes, that’s a much more important point than the argument most associated with Dworkin, the formula of penetrative-sex-equals-rape. That formula becomes more of a tactical maneuver - scrutinizing sex acts with the onus on male coercion rather than female consent. As an injunction, or basis for any kind of law, the absolutist version of penetrative-sex-equals-rape is unworkable and deleterious. But it does help to reframe the way we think about sex - as a fraught space, in which there are no easy answers, and in which everybody is accountable for their actions.

SINGER AS HERETIC

There are a couple of lines from this Adam Kirsch piece on Isaac Bashevis Singer’s non-fiction that really hit me. One is Singer writing sometime around the 1940s, “I believe that this generation is beset by the worst devil the netherworld has ever sent to mislead us.” There were of course many record-setting devils sent by the netherworld around this time, but Singer had a particular one in mind - “that the Satan of our time plays the part of a humanist and has one desire: to save the world.” And, in the other line that got to me, he described in more detail a quality of that particular devil: “Literature was doomed when writers began to feel that the past was not so important…that the main thing was would happen in the future.”

That jibes with a suspicion I’ve had for awhile, that our era, at least in the aesthetic dimension, is sort of replicating the ’30s and ’40s. There’s a very heavy dose of idealism on the progressive left - a belief that everything must be dedicated to some sort of political utopia. In the early to mid 20th century that utopia took economic form - in dialectical materialism. Now it’s airy social justice. And the idealistic mindset is linked always to a very pronounced sense of presentism - the idea that the past exists only as a sort of rehearsal for the present and future, has no intrinsic value to itself, and can be easily dismissed as superstitious and error-ridden.

For Singer, that ideologically-driven presentism generated a torrent of terrible art (socialist realism and the equivalents by Western fellow-travelers) and it helped to clarify his own aesthetic beliefs - an alliance with the ‘superstitious’ past; a suspicion of high-minded idealism; and, as Kirsch puts it, “faith in individuals and stories rather than collectivities and ideas.”

And there’s something from that to apply to art’s current impasse. Singer had an opportunity to write from a progressive vantage-point - to write in Hebrew, the elevated language of Zionism, to embody a sort of model minority at a moment when the publishing world evinced an appetite for the ‘Jewish experience.’ Instead, as Kirsch writes, Singer opted for “a modernist convergence” - an interest in “the sick, the ugly, the extreme,” which was far more central to his work than his stories’ surface impression of being identitarian, pastoral, rooted in the experience of a particular community - and it was precisely that bid for finding the universal in the narrowly individual, in the bizarre singular, that, as Kirsch puts it, made it possible for Singer “to become famous outside of Yiddish….for the ordeals of his characters to feel quintessentially modern.”

But there has always been a suspicion of Singer’s work precisely from the the Yiddish community that he came to embody. “I profoundly despise all those who eat the bread in which the blasphemous buffoon has urinated,” said the particularly splenetic Inna Grade, whose husband, the writer Chaim Grade, had been Singer’s principal rival for the role of Yiddish literary spokesman. It’s exactly this sore point that’s the subject matter of Cynthia Ozick’s short story ‘Envy: Or Yiddish In America’ - a writer Edelshtein reduced to embittered sputtering over the successes of a Singer-like antagonist Ostrover who, in the midst of the greatest cultural apocalypse conceivable, had decided to mine his heritage for embarrassing tidbits. “Little jokes, little jokes, all they wanted was jokes!” reflects Edelshtein of Ostrover. And, meanwhile, “The language was lost - murdered. The language - a museum. Of what other language can it be said that it died a sudden and definite death, in a given decade, on a given piece of soil?”

That story actually made a tremendous impression on me when I read it as a teenager - it was my introduction, really, to the vast archipelago of unfulfilled and overlooked artists and to their very concerted gripes against the rivals who had upstaged them. To me at the time, Singer seemed like the kind of writer nobody could possibly object to - genial, light-hearted, with a winning sense of weightlessness - and it was very arresting to encounter, in fictional guise, the army of the disgruntled, who clearly felt that Singer’s success was a kind of coda to the cultural apocalypse.

In the end I don’t quite see what - other than envy - made Edelshtein and Inna Grade object so vehemently to Singer. I read his fiction and I see teasing of the Yiddish community he grew up but not disrespect. Kirsch, attempting to explicate the objections to Singer, writes, “In his novels and stories he is drawn to the most dangerously combustible elements in Jewish tradition—to false messiahs, kabbalistic magic, and demonic possession.” The sense is of a betrayal - Kirsch uses the word ‘blasphemy’ - in two different directions. There’s the matter of messaging, the charge that Singer was airing out dirty laundry, playing into anti-Semitic stereotypes, giving Jews a bad name - the same accusation that American Jews made against early Philip Roth. And then there’s a hint of something more trenchant, a suspicion of ‘universality’ itself. That’s what the Singer-like Ostrover in ‘Envy: Or Yiddish in America’ taunts Edelshtein with - the idea that language, culture, all of these things, are really just a kind of thoroughfare and that all that matters is ‘talent,’ which is no way culturally constrained and is recognizable to anyone - and it’s this thought above all that sends Edelshtein into his “furious and alien meditation.”

The real-life Singer put this in very direct terms. “In art a truth which is boring is not true,” he wrote. But Edelshtein, in his furious meditation, finds the commitment to not-boringness to be actually very dull. “Jokes, jokes! It looked to go on for another hour. The condition of fame, a Question Period: a man can stand up forever and dribble shallow quips and everyone admires him for it,” he fulminates, watching Ostrover give a reading. And this kind of shallowness - just annoying and consumerist in better circumstances - comes across as a massive affront to everything holy and decent in the wake of the Holocaust. Singer genuinely believed that art had no greater purpose than entertainment - “writers are entertainers in the highest sense of the world,” he wrote. But Edelshtein, in his fury, and with the fulness of Jewish history animating him, seemed to point towards something better - an idea that boredom, the apparently uninteresting - was not some sort of frontier that art could not pass over. That what mattered ultimately was truth, wherever it was found - and the artist’s responsibility was to honor truth, palatable or not, boring or not. If two writers found themselves from the same decimated Yiddish community, the weak path was to transmute that particular experience into a sort of universal quip; the strong path was to stay with something quintessential about that community, even if the work remained parochial as a result. As Edelshtein tells Ostrover in their eventual confrontation, “Once there was a ghost who thought he was still alive. You know what happened to him? He got up one morning and began to shave and cut himself. And there was no blood. No blood at all. And he still didn't believe it, so he looked in the mirror to see. And there was no reflection, no sign of himself. He wasn't there. But he still didn't believe it, so he began to scream, but there was no sound, no sound at all—”

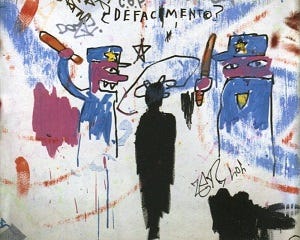

THE GUGGENHEIM AS ANACHRONISM

The Atlantic has an extraordinary story about the Guggenheim’s meltdown in the midst of culture wars. It’s the kind of story that everybody’s gotten sick of hearing and has come to define our era - a liberal-minded institution attempts to rectify historical and racial injustices in a measured way and, instead, the institution finds itself accused of structural racism and its white employees, while issuing apologies as fast as possible, have their careers ruined.

What’s most obviously striking about this piece is that it’s in The Atlantic at all. The pillars of liberal media spent the crucial period of cancel culture’s advent….pretending that cancel culture didn’t exist at all. The usual strategies have been to claim that ‘cancel culture’ is a sort of right-wing disinformation campaign or to insist on a moral equivalency between much-publicized progressive cancellation efforts and the if-anything-more-dangerous initiatives of the right. “Cancel Culture Isn’t The Real Threat To Academic Freedom” ran an Atlantic headline in November, 2021. “Partisans, especially on the right, now toss around the phrase cancel culture when they want to defend themselves from criticism,” wrote Anne Applebaum in The Atlantic in August, 2021. “Where’s the cancel culture outrage over burning books?” ran an Atlantic newsletter piece by Molly Jong-Fast in February 2022. “Joe Rogan is still here, but books are disappearing from libraries.”

This spring the legacy liberal media took a curious about-face and declared that, cough-cough, cancel culture does exist. “Although I dislike the term cancel culture because of its vagueness and potential for misinterpretation, I tend to think that “cancel culture” is a problem,” conceded Conor Friedersdorf in The Atlantic. And, in March, The New York Times put cancel culture on the record with the famous editorial “America Has A Free Speech Problem.”

During the long period before cancel culture officially existed, debates about institutional meltdowns like the Guggenheim’s raged everywhere - it was to a great extent the founding impulse for Substack and the preeminent Substacks, Bari Weiss’ Common Sense, Matt Taibbi’s TK News, etc, tend largely to be an endless rehashing of these sorts of debates - except in the legacy media outlets that, in theory, had the greatest vested interest in freedom of speech. And now, finally, belatedly, there’s a good old-fashioned reported piece in The Atlantic on the collapse of the Guggenheim and some sense that the mainstream media has once again chosen to be interested in stories like this about the kinds of things that really matter a great deal to people.

What’s striking as well about The Atlantic’s piece is the recognition that the problem has become so intractable that there really is no viable solution. An institution like the Guggenheim simply cannot rectify its ‘historical racism’ because so many on the progressive left see the Guggenheim itself as illegitimate, so tainted by ‘racism’ and ‘white supremacy’ that any sort of attempted process of rectification is just platitudinous and placating and itself an insult. A publication like The Atlantic can’t act as any sort of a meditator because The Atlantic is illegitimate for all the same reasons. As Chaédria LaBouvier, curator of the contentious exhibit ‘Basquiat’s Defacement: The Untold Story’ at the Guggenheim, wrote in a response to The Atlantic’s request for an interview. “Fuck you and your arrogance….I am not interested in participating in a piece that through lack of expertise, thoroughness, research or fortitude will resign me as a footnote and amplify a glorified publicity stunt,” she wrote and described Helen Lewis, the piece’s author, as “another example of a clueless, rapacious White woman.”

There aren’t a lot of satisfying conclusions to draw from a situation like this. It’s a conflict and as in all conflicts everybody has to choose what matters to them. The first lesson is the certain types of conciliation and moderation just don’t work. It doesn’t work to arrive at some ideologically-agreed-upon consensus - as LaBouvier makes clear, the issues fundamentally aren’t ideological, it’s about who has power. (The great dealbreaker in LaBouvier’s relationship with the Guggenheim was that she was not included to speak on a panel related to her exhibit.) It doesn’t work for the institution to hear all voices, to attempt to triangulate towards some sort of happy medium - there’s too much of a question about the legitimacy of the institution itself. (As LaBouvier said of the existence of the multiracial panel, “To weaponize a panel of Black bodies of color to do your filth is insane. This is insane. And this is how institutional white supremacy works.”) And, when subject to the kind of ferocious scrutiny that LaBouvier applies, all sorts of convenient assumptions turn out to be more fragile than they usually are seen to be - why should the museum administration get to decide who sits on a high-status panel and who doesn’t? why does a museum get to have a pretense of objectivity when displaying work that replicates traumatic historical moments? why, come to think of it, does a museum with its own flawed history get to decide which art is of value and which art isn’t?

As it turns out, moderation, institutional legitimacy, the whole liberal legacy, rest on some very frail beliefs - essentially, a civil society and artistic community that’s willing to buy into them. The crucible of the woke wars basically breaks these institutions - the Guggenheim ends up throwing its own chief curator under the bus even though an independent investigation determines that she did nothing at all wrong. It’s simply not possible for them, however much they try, to be both progressively irreproachable and to honor their own institutional traditions. So everybody has to make their choices. In a way, I respect LaBouvier’s actions through this controversy more than I do the endlessly moderate, endlessly self-flagellating Guggenheim administration. For LaBouvier, artistic expression clearly is a matter of life and death - and that matters far more than institutional legacy. When the Guggenheim attempted to edit an essay of LaBouvier’s claiming that it was “poorly written and lax in its scholarship,” LaBouvier - as she afterwards wrote - “said fuck no & fought back.” And I agree with that fire - if with nothing else in LaBouvier’s position. Art comes from sweat and tears - and from artists working at cross-purposes from one another. It’s silly to pretend that art is as smooth as an institution like the Guggenheim inevitably pretends it is. Art museums turn out to be a very frail exercise - and easily blown over by a political wind like the woke wars. But art itself is much tougher than that and deserves to be in the hands of people who - whatever their vision - are willing to really fight for it.

Glad you clarified that Dworkin didn't exactly say penetrative sex is rape (although close enough!). There's more to her than that.

*Smoothing